We look at the impact on progressive music of John Lennon and his three musical pals...

Issued in June 1967, The Beatles’ eighth album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, was a milestone in pop music. Having retired from live work the previous year, the Fabs were free to experiment in the studio, creating songs that transcended the tired notion of verse-chorus-verse. In its place came ambitious arrangements and complex sound structures, bringing together a spread of influences – classical, rock, music hall, Eastern music, psychedelia, the avant-garde – to deliver a fantasia that served as the first populist concept album.

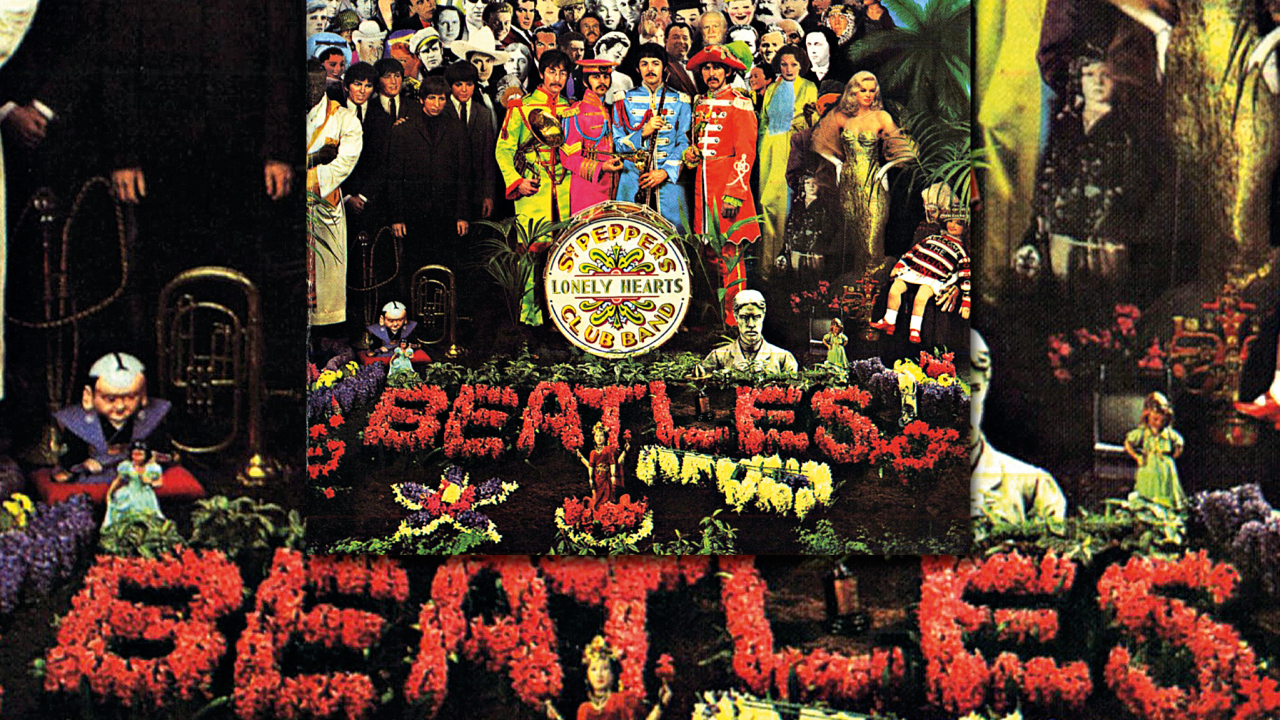

And let’s not forget the packaging. The gatefold sleeve, designed by British pop artists Peter Blake and Jann Haworth, presented The Beatles as alter-egos from some gaily-attired Edwardian band, complete with cardboard cut-outs and a grand tableau of cultural figures. It was also the first album to feature printed lyrics on the back. Times critic Kenneth Tynan may have been guilty of hyperbole when he called Sgt. Pepper “a decisive moment in the history of Western civilisation”, but it was certainly an event.

In its wake, albums became more important than singles. They became artistic statements, often linked by an overriding theme. But while there’s no denying Sgt. Pepper’s impact and popularity (to date it’s sold over 30 million copies), how significant was it in the development of prog?

Let’s start at the top. King Crimson are generally accepted as one of the pre-eminent prog bands with releases like In The Court Of The Crimson King, In The Wake of Poseidon and Lizard. Robert Fripp has made no secret of the fact that hearing the orchestral grandeur of A Day In The Life, arguably the most iconic track on Sgt. Pepper, was “incredibly powerful.” He once said that “something opened up” when he heard it on the radio.

(The Beatles info is at 3:07)

As early as 1969, Crimson were covering Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds at rehearsals. Though perhaps the band’s most overt acknowledgement came a year later, when Happy Family – one of Lizard’s most enduring songs – bemoaned the messy break-up of The Beatles. Fast forward to 2000’s live album Heavy ConstruKction and you’ll find Tomorrow Never Knew Thela, which fuses Thela Hun Ginjeet with John Lennon’s Sgt. Pepper precursor, Tomorrow Never Knows. This wasn’t all Fripp’s doing either. Guitarist Adrian Belew was a huge fan of The Beatles’ Revolver/Sgt. Pepper period.

Other debts of gratitude from the land of prog have come from Pink Floyd. In particular, the clutch of singles that immediately followed Sgt. Pepper. The lyrics of Apples And Oranges quote the title track at one point (“Thought you might like to know”), while Paintbox carries the tangible scent of A Day In The Life. It was a fascination that reached its ultimate form of expression in the sweeping orchestral sections of Atom Heart Mother. Perhaps most striking of all is Floyd’s appropriation of Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds on 1968’s Point Me At The Sky.

Floyd’s early producer Norman Smith, formerly The Beatles’ engineer, also brought his presence to bear on The Pretty Things. Rock opera S.F. Sorrow utilised the same Abbey Road studio as Sgt. Pepper, with the band following a lead by introducing an overarching theme, Eastern tones and unusual song constructs. Meanwhile, The Moody Blues were busy creating late ‘60s concept works like In Search Of The Lost Chord and On The Threshold Of A Dream. “The Beatles were the leaders in everything,” Justin Hayward said recently. “Whatever they did, people followed. And we started to empathise with that.”

There are plenty of further examples. John McLaughlin revealed that he flipped out when he first heard Sgt. Pepper. US composer Carla Bley spent three years in a quest “to match” the album with 1971’s avant-jazz opera, Escalator Over The Hill. And the symphonic splurge of the Blossom Toes’ We Are Ever So Clean owed more than a little. Referring to the influence of their then-manager, one contemporary review even called it “Giorgio Gomelsky’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”. Meanwhile, Frank Zappa’s infamous parody of The Beatles’ original, We’re Only In It For The Money, may not have been affectionate, but it did at least flag up Sgt. Pepper’s cultural significance.

Of course, it’s debatable whether Sgt. Pepper is a prog album at all. In fact, it really isn’t. The tropes that came to define the music of ELP, Genesis and Yes – liberal keyboards, tricky interplay, rare time signatures and extended improv – are hardly present at all. And Zappa’s Freak Out!, among others, beat The Beatles to it when it came to concept pieces.

But Sgt. Pepper remains a vital signpost to prog rock by way of its vivid ambition and an overwhelming desire to break free of the accepted confines of pop music. Plus there’s the matter of that fabulous sleeve, which gave licence for others to frame their music in suitably progressive visuals. In that respect, Sgt. Pepper is still the yardstick by which all populist musical endeavour is measured. Bill Bruford, a man who knows a thing or two about prog, once opined that, “Without The Beatles, or someone else who had done what The Beatles did, it is fair to assume that there would have been no progressive rock.” Go figure.