I waited a long time for David Bowie to die.

When The Next Day came out in 2013 - suddenly, with no adverts, no promo interviews or TV appearances – I thought, “Ah-ha. I see what you’re doing. Not bad for a dead guy”. And I smiled, read the ecstatic reviews and waited for the news that the album had been recorded at some point in the previous decade and David Bowie had in fact passed away, weeks – maybe months – before and buried in a private ceremony somewhere.

And I waited and waited. And, well, it got silly, but it stuck in my head and I started to get facts confused with dreams, dreams with rumour, rumour with reality (did the Flaming Lips really record a song called Is David Bowie Dying? Answer: yes) until I couldn’t remember for certain if Bowie really was dying or not.

The story came from a weird source, you see. A guy who used to work for us, who’d gone on to bigger and better things. He told us that one day he’d been in the company of an A-list rock star when Bowie’s name came up and A-List had shaken his sad old head and said, “Bowie’s dying. He’s got cancer, terminal cancer. He’s only got months to live.”

It was the tail end of 2012*.

“You can’t tell anyone,” our man said, suddenly aware that he was talking to a blood-thirsty pack of click-wolves. “If you do, they’ll know it was me who told you.”

Our pupils shrank and we wiped the slobber from our chins. Us wolves have got to stick together. And anyway – how could we prove it? It had to stay a secret. So we sat back and we waited. We lay around the fire picking on bones and chewing it over.

We toyed with getting his obituary written in advance and eventually decided against it. Not because it would mean telling someone The Secret – we could bluff that – and not because it seemed too cynical either: but because the truly cynical part of us realised we’d get better material if the obit was written in the emotional fallout from his actual death.

We planned a cover story, a timeless story about Aladdin Sane that we could run anytime, and then dropped it from the cover and ran it anyway. It was too good to sit on. Other magazines were running Bowie covers. Wolves everywhere were picking up the scent. We had to be coy. Lay low.

And as time wore on, I stopped thinking about David Bowie dying. The scent of blood faded. The wound scabbed up.

In the last couple of weeks, people have said that they’ve found it hard to believe he’s really dead. I found it harder to believe that he’s been alive this whole time.

In 1983, when I was 12, Bowie released Let’s Dance. It was one of the few records my big sister and me agreed on. She’d given up on Madness, The Jam and The Police and moved on to a bunch of bands in slip-ons and pleated trousers – ponces with blow-dried hair, perfect teeth and perma-tans – and we’d ceased to have common ground.

But then, this. A shuddering, bare-foot-a-slapping-on-the-floor, bass-heavy pop classic delivered by some guy in slip-ons and pleated bloody trousers, complete with golden tan, blonde quiff and dangerous white teeth. I had been vaguely aware of Ashes To Ashes – it had been no.1 in 1980 when I was 9 – and the video was weird but the song stuck in your head like a fever. The Let’s Dance David Bowie was a world away from the freak show in that video. This guy was clean cut, healthy, happy and had a charisma matched only by Elvis in the movies we watched in our summer holidays

This was how I first discovered Bowie. Since then, I’ve spoken to rock stars who had their minds blown by seeing Starman on TOTP, whose dads gave them funny looks when they dyed their hair purple. My Bowie was dad-friendly. Cool. A ‘ladies man’ – a famous international playboy shagging on the beach – but with depth: tragic like Marlon Brando, visions of swastikas in his head and plans for everyone. A man who knew when to go out and when to stay in, get things done.

My sister was 15. She had a boyfriend and he gave her Changes One and Changes Two. This boyfriend, it turned out, was mad-about-Bowie: mad-about-him in a way I had never come across before but would later become very familiar with. He was the first guy I ever knew who could tell you who’d played bass on a record, who’d produced it, who’d written the songs, which order the albums were released in, all that stuff.

Me and my sister devoured the Changes albums. She got a loan of Ziggy and Hunky Dory, Aladdin Sane and Low. He’d give her related stuff too: Mott’s Greatest Hits album, Lou Reed’s Transformer. Stuff that I think of now as, like, the best rock music ever made.

The first thing I learned to play on a guitar was the opening chords for Ziggy. The second was Hang On To Yourself. I bought a magazine all about Bowie. By the time I had my own money, I’d go to Glasgow and blow it all in the Virgin Megastore, coming home with “Heroes” and Raw Power, Berlin and The Hoople, and new stuff that couldn’t have been made without those records: Bauhaus, Bunnymen, Flesh For Lulu, Sisters…

It goes without saying that David Bowie let me down almost instantly. Tonight, the follow up to Let’s Dance, was a lot harder to love. Labyrinth (1986) was an embarrassment. The concept of “a career arc” was something I was beginning to understand, later expertly outlined by Sick Boy in Trainspotting:

Sick Boy: Well, at one time, you’ve got it and then you lose it and it’s gone forever. All walks of life: George Best, for example. Had it, lost it. Or David Bowie, or Lou Reed…

Renton: Lou Reed? Some of his solo stuff’s no’ bad.

Sick Boy: No, it’s no’ bad, but it’s not great either. And in your heart you kind of know that although it sounds all right, it’s actually just shite.

Renton: So who else?

Sick Boy: Charlie Nicholas, David Niven, Malcolm McLaren, Elvis Presley…

Renton: Right. So we all get old and then we can’t hack it anymore. Is that it?

Sick Boy: Yeah.

Renton: That’s your theory?

Sick Boy: Yeah. Beautifully fucking illustrated.

Some people choose their favourite bands and artists like they do their favourite football team – they tie their colours to the mast and stick with them forever, through the good times and the bad. Others accept that you’ve got it and then you lose it. And off they go looking for the next person who’s picked it up. Ooh bop, fashion.

Following Bowie was not like following Aston Villa. For all the outpouring of grief right now, Bowie fans were among the most promiscuous and lupine. Bowie made us this way: part wolf, part peoploid. It’s how he lived too. He needed Mick Ronson and the Spiders to transform himself from a struggling acoustic hippy songwriter at the end of the 60s to the ultimate electric rock god of the early 70s.

And when he felt that was done, he dropped them and moved on – to Luther Vandross and Carlos Alomar, or Brian Eno or Nile Rodgers – whoever could take him where he wanted to go. And he didn’t look back. I never really liked a Bowie record after Blue Jean.

Someone I’ve interviewed since – Lemmy, I think, but maybe Ian Hunter – told me that the music you get into when you’re 14 is the music that stays with you forever, that nothing will ever sound as good as those songs.

At 14 I was in a world created by David Bowie. My body was in a council house in the west coast of Scotland, our streets covered in imported iron ore spilling from the strike-breaking trucks that that we chased after shouting “Scaaaaab!”, but my head was elsewhere. In a panic in Detroit. In Berlin, by the wall. In a moonage daydream.

I was 14 and Lemmy/Hunter was right: nothing will ever sound as good to me as the last four songs of Ziggy Stardust.

My alarm went off. The radio was playing a David Bowie song. I put it on snooze and woke up five minutes later to Space Oddity. I sat up in the dark and said to my wife, the room or myself: “Don’t tell me David Bowie’s dead…”

I checked the BBC and then texted my News Editor. We already had the story up. 100% wolf.

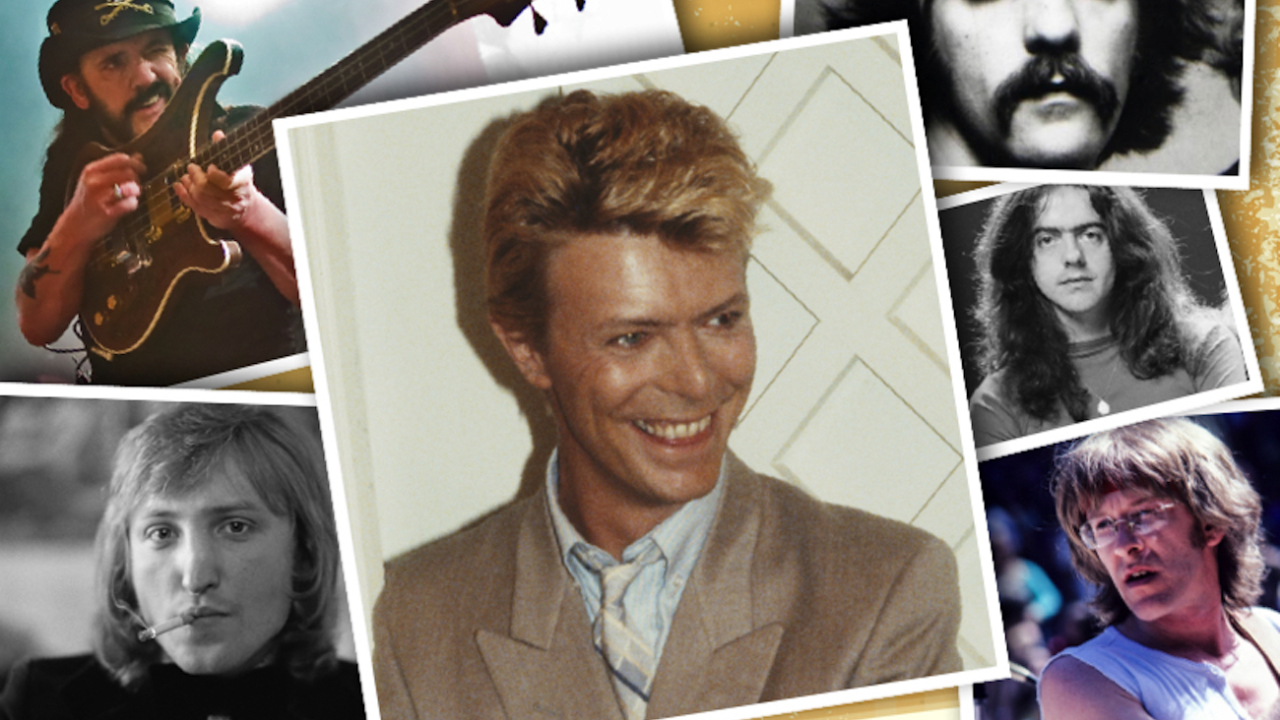

Turning memories into stories that can be liked, clicked and shared has become part of my job. I – we – had better get used to it: there’s a whole generation of rock stars whose deaths we’re going to live through together. The most remarkable thing about Lemmy, Bowie, Dale Griffin, Glenn Frey, Jimmy Bain and Paul Kantner dying within weeks of each other is that we haven’t had a freakishly bad run like that before.

Think about it: movie-going, pop-culture, and rock’n’roll really took off in the 50s and of that first flush of Hollywood and rock’n’roll anti-heroes many are still with us. If they were 20 in 1956 – an original rock’n’roller – they’re 80 now. If they were 20 in ’66 – an original hard rocker – they’re 70.

Now think of the bands you like. Three to five members in each one, line-up changes and session guys swelling the ranks. Think about how many bands you like. You’ve probably never considered it but – if you’re a serious rock fan with an open mind and a taste that covers every generation from the 60s – you like hundreds of bands. And if you’re a real geek, you probably know the names of most of the people who played in them.

That’s a lot of people.

In my iTunes right now I have 3,993 albums. That’s not my entire collection either - I have thousands of CDs, on shelves and in wallets all over my house, and maybe 1000 vinyl records, many of which are not duplicated in iTunes. I just went through the artists under ‘A’ and I reckon that a significant death in 29 of them would make rock news headlines.

Let’s do some really bogus maths: say there’s four people in each band, that’s 116 possible deaths. If the figure is the same for every letter in the alphabet (it won’t be - as anyone who’s alphabetised their record collection knows, your ’S’s are stupidly huge and X,Y and Z are puny - but it’ll do) then at 116 x 26, as a rough average, that’s 3016 people who played a part in making the music I love.

They’re not all older than me, and obviously I might go before them, but I reckon it’s a safe bet that I’ll live to see at least 1000+ of them die, maybe twice that.

Some time ago on Classic Rock we made a decision: that we wouldn’t just write about the musicians we love as they were back in the 70s when they were making their classic albums and living the high life. We’d write about them now, too. While other magazines and newspapers laughed and sneered at ‘wrinkly old rockers’, we’d try to chronicle them in a dignified way.

We’d let them speak, we’d show them respect, shoot them in the most flattering light possible. We’d give them awards and celebrate their achievements, listen to their new music and tell their stories now, while they’re still alive.

Old actors fade from public life – the roles dry up, prettier faces come along, the media shifts its focus – but old rock’n’rollers stay in the limelight. The first generation of rock stars to reach old age are doing so in the media eye: musicians with active and engaged fan bases, still out working in the long tail of their career arc – still touring, releasing music and heading festivals and stadiums.

It gives us a false sense of security. We’re still watching the same bands we did when we were kids. Nothing has changed. You could be fooled into thinking nothing ever will.

Music writing used to be about lauding great bands and destroying shit ones - now everyone can do that on social media. When Jimmy Bain died, it was all over Facebook before Bain’s family could even be notified. (Congratulations: we’re all wolves now.)

Awestruck, we used to read stories about sex, drugs and rock’n’roll – now we all know where to get Class As, sex is at the end of a smart phone app and anyone can behave like a rock star for a weekend.

Our rock stars taught us well. They pioneered hedonism. We learned from their overdoses, breakdowns and ‘orrible concept albums. Now we’re going to learn how to face the end.

This isn’t a spate. Of all the cliches trotted out at these moments (“We will never see their like again” is my most hated), one is bang on: it is literally the end of an era.

*You can’t trust anyone. Because I guess A-List got it wrong. Tony Visconti has said that Bowie himself didn’t know it was terminal until November 2015. This is the thing with people who tell stories: you can’t trust them.