The Tangent bandleader Andy Tillison talked to Prog about travel shows, anti-Tangent sentiment, and the rather surprising artist he’d really like to work with when the band released their twelfth studio album Songs From The Hard Shoulder in 2023...

Andy Tillison has had an intriguing and varied professional journey. Although he fell in love with progressive rock at a young age, his first bands were new wave/pop acts and he owned and ran a studio in Leeds in the 1980s, which became a magnet for anarchists and punks. Soon he was rubbing shoulders with seminal British thrash and hardcore bands such as Civilised Society? and Carcass, as well as establishing a lasting relationship with anarcho-communists Chumbawumba.

During the 1990s, he fronted a band heavily influenced by those studio experiences called Gold Frankincense & Disk Drive – their debut album, Where Do We Draw The Line?, was the first release on Peaceville Records, later home to Opeth and Anathema – then released a series of neo-prog/art-rock albums under the banner of Parallel Or 90 Degrees (aka Po90).

However, it’s his work with The Tangent for which he is undoubtedly best known. Through this band and associated projects, Tillison has come to work with many major names in contemporary prog. Some 20 years since The Tangent made their debut with an unabashed homage to English progressive rock, The Music That Died Alone, as a one-off expanded solo project, Andy Tillison sits in his studio in deepest Yorkshire surrounded by a plethora of keyboards, microphones and esoteric outboard gear discussing the band’s latest release.

“We’ve made 12 studio albums now, which is the equivalent in Yes terms of reaching Big Generator. It’s not cosmically important but I feel a certain sense of pride – are we still here?” he asks with a genuine air of incredulity. “We still have a record company who believe in us and put our music out there for us.”

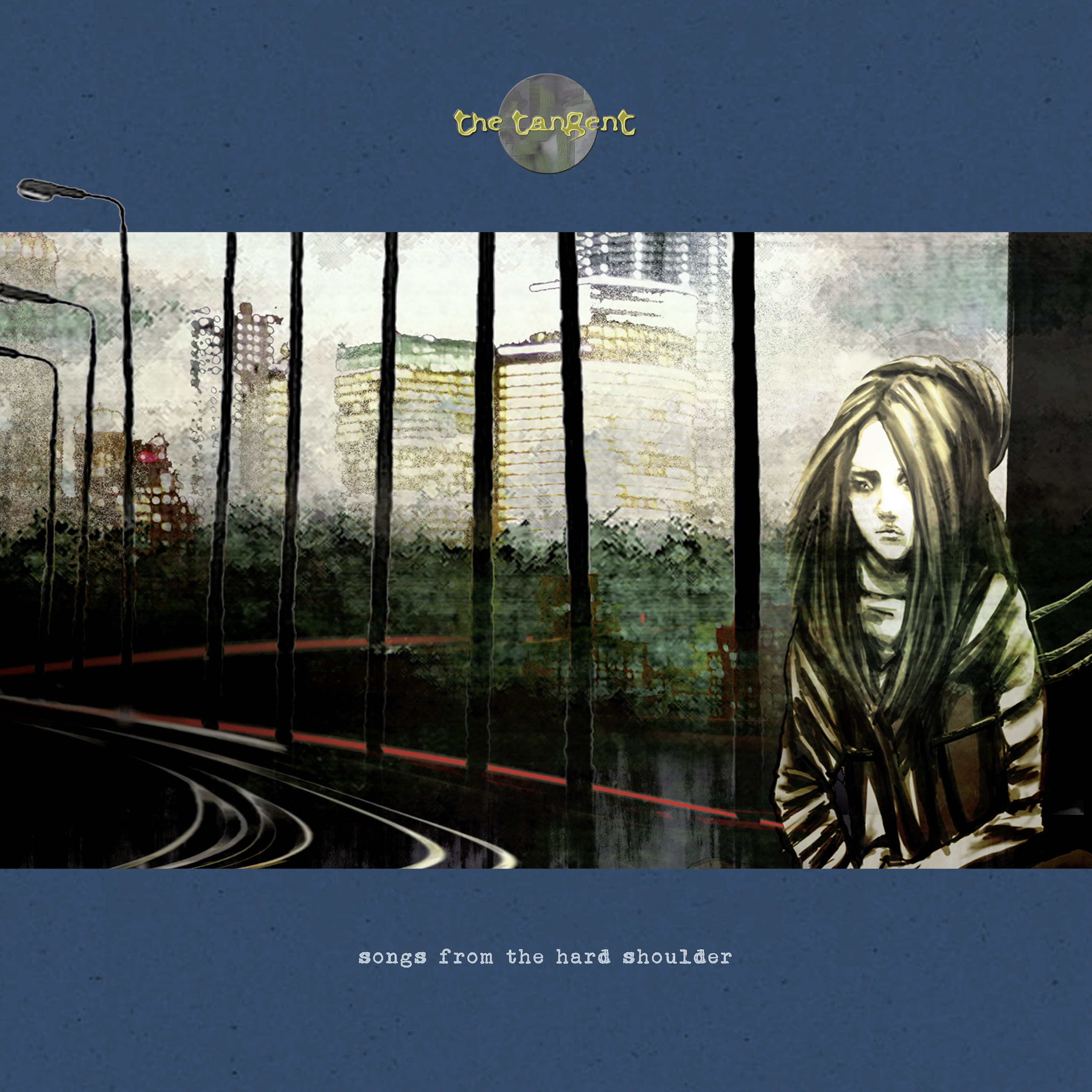

Described by Tillison as “the difficult 12th album”, Songs From The Hard Shoulder contains just four tracks (with the added bonus of a cover of UK’s In The Dead Of Night). Three of them clock in at over 17 minutes and develop thematic concepts that he’s been toying with for years.

“It’s built on an idea dating back to the anarcho-punk band, Gold Frankincense

& Disk Drive. I used the image of the hard shoulder as a place where people who weren’t doing as well as everybody else watched the rest of the world go by. In fact, that band’s second album was subtitled A Fractured View From The Hard Shoulder.

“Musically, the focus was all about composition; to go deep into writing complex, super-organised musical adventures. A lot of classical formats have been followed here: musical techniques like recapitulation, themes, variation, and improvisation to make an album that is essentially a series of stories or journeys that I want to take people on.”

The Tangent have a long history of songs built on stories and narratives, whether it’'s the reminiscences of an ex-World War Two fighter pilot in In Earnest from 2006’s A Place In The Queue or the more personal and literal journey described in Jinxed In Jersey from 2020’s Auto Reconnaissance. The Changes, from the current album, uses small vignettes from The Tangent on tour to similar effect. Written during the UK’s first lockdown, it captures a unique set of experiences and emotions.

As Tillison explains, “It was a period of our lives that will probably never come again. It was so quiet, so alien… I think everybody was on the hard shoulder. We weren’t watching the traffic in the fast lane thinking: why can’t I be with them? We were all just broken down by the roadside. I decided that I wanted to mention the band in the song as friends, not as fellow musicians necessarily. What I was missing wasn’t the stage, the action, all that stuff; it was the daft moments – trying to find a hotel or the night when bandmember X was absolutely outrageously drunk and we had to rescue him from something terrible. The minutiae of being on the road that really piss you off but you look back and smile about them. The song goes on to include football supporters, plumbers; everybody trying to deal with this. When you have songs as complicated as that lyrically, unless you’re a genius like Brian Wilson, you can’t say it in three minutes – you need time to take people on that journey. We all like watching a good travel show, like Michael Palin doing Pole To Pole or Ewan McGregor and Charley Boorman on their motorbikes [on Long Way Round], that’s what The Tangent does: we make musical journeys. We’re the Alan Whicker of prog!” he exclaims with a laugh.

Instrumentals have become a regular feature on The Tangent’s albums, an aspect continued here with the sprawling The GPS Vultures, which allows the band to stretch out a bit with some stunning solo work from Luke Machin and Theo Travis.

“Back on our third album, A Place In The Queue we had a song called GPS Culture – a bit of a favourite for Tangent fans – what we’ve done is come up with the idea of classical variations, like Elgar and Paganini. It’s not the same song at all, it’s not a ‘part two’ or anything, it’s just another piece of music utilising techniques and chord shapes that I used to make GPS Culture. There are leitmotifs that tie it together, but it’s a separate piece. I’ve never been to music school, I can’t read music and have spent a long time working with people who use very complicated words that I don’t really know the meaning of! I’ve been learning from these people over the years and my composition has developed. There are a lot of influences: I’m a very big fan of an obscure Swedish keyboard player called Bo Hansson, who made three really amazing albums in the 1970s and never got the credit he deserved and I used a lot of inspiration from him.”

Taking positions on social and political issues is part of The Tangent’s DNA. The Lady Tied To The Lamp Post deals with the enduring problem of homelessness juxtaposed against human beings’ ability to invent and solve in so many other areas. “It’s based on an actual event that happened in 2013 or thereabouts,” Tillison explains. “We had a college staff Christmas party. Making my way to the bus stop afterwards, I nearly tripped over this poor woman literally tying herself to a lamp post. If she didn’t tie herself up she would fall over while she slept and she didn’t want to sleep with her head on the concrete. I spoke with her, gave her some cigarettes and found out that just weeks before she’d had a life and a job: it could have been me. It was terribly sad.” He sighs and pauses for a moment, “but I didn’t do anything else – I got the bus and went home, because it was late and it was the middle of winter in the middle of Leeds. The number of things that human beings can solve is unbelievable, so why are there still people without places to sleep or something to eat in the middle of these prosperous cities? I sometimes think that I’m a very naïve person, a lot my songs are full of naïveté, but mainly it’s just me thinking out loud: well why don’t we do that? All the clever, grown-up people have had a go, give the naïve people a chance!”

While not alone in the prog world in voicing potentially contentious positions, does Tillison worry about negative backlash from being so relatively outspoken sometimes? “Yeah I do, naturally I do. There are ‘Hate The Tangent’ threads out there on the internet, there are people in certain areas east of Austria who don’t necessarily like some of the things we do. I just feel from time to time you have to take the risk. I’ve made no secret that I really think Brexit was a terrible mistake, for instance, and I wrote a song about it. [A Few Steps Down The Wrong Road from The Slow Rust Of Forgotten Machinery]. The ironic thing is, after it was released, I thought: where’s everybody else? Where are my punk friends? And there’s just bloody me standing here with a prog rock band singing about Brexit feeling very exposed,” he says with faux-indignation.

“I get grief from some of our own fans, because we have fans of all political persuasions, but all I’m really doing is trying to pose a series of questions. I don’t want to slag people off – there’s too much of that in the world – but I’m still going to sing about homelessness and poverty and racism because they concern me. The pandemic and a lady tied to a lamp post in an inner city are depressing, but if you want to create something uplifting you need the triumph of a journey through the dark towards the light.”

Wasted Soul – the shortest track on the album – suggests a northern soul/Motown influence, or is Prog reading too much into it? “When I was at school everybody was into Showaddywaddy and the Rubettes, and there was just one single black lad – I was already into my prog and I bumped into him and he had an album with a Roger Dean cover… and it was Osibisa! That guy single-handedly introduced me to Earth Wind & Fire, the Temptations, the Four Tops and all this stuff. I just love that music, it’s part of the soundtrack of my life and the same with disco. I mean I love prog, but the likelihood is that your first kiss or sexual awakening will not have happened to Yours Is No Disgrace, it’ll be in the middle of Heat Wave or Boogie Nights!” he laughs. “I spent ages on Wasted Soul to try to get it just right – possibly longer than on any of the other tracks on the album. Listening back it’s probably got more Commitments and Dexys Midnight Runners to it, but I’m happy with it. Also, with everything else on the album, it’s a little slice of ‘hey, let’s party’ to add a bit of light.”

Conversation turns to influences and there’s a very long list – he’s as comfortable talking about Trent Reznor and Stockhausen as he is referencing The Aphex Twin and Squarepusher – the latter impressing Tillison greatly. He talks about musical and cultural melting pots and the importance of lyrics, which leads to Neal Morse – “I really, really like his lyrics and that he fucking believes what he sings,” he enthuses. “I’m a professed atheist, but I’d love to work with Neal because I think it would be really interesting to see what a totally, amazingly Christian guy like him and a non-religious guy like me could do together. I think we might find something good that may actually save the world,” he shrugs, “but I’m not sure he knows who I am…”