"A lot of people think it’s about Vikings, but it never was." We took Wardruna's Einar Selvik foraging in one of London's oldest graveyards

Wardruna's Einar Selvik explains the importance of nature his band's animistic worldview

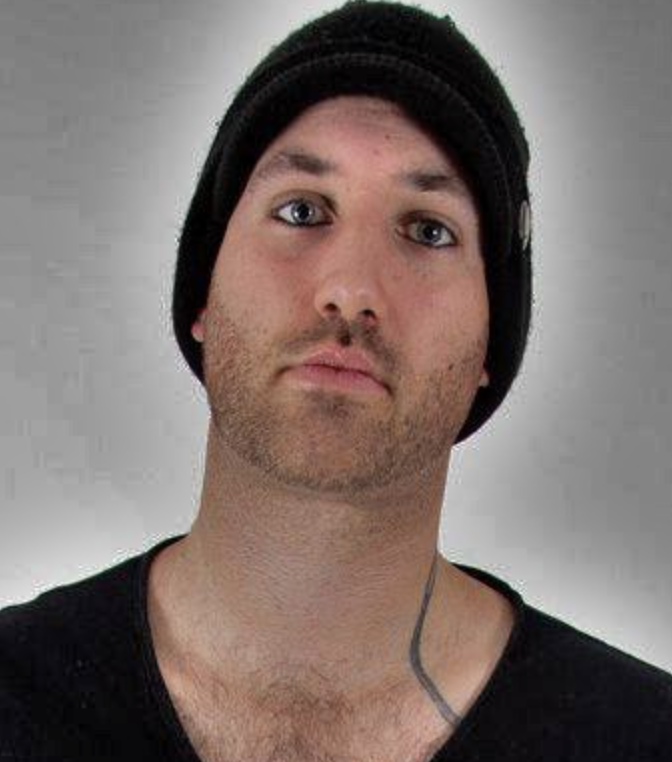

"Come on, man!” barks Wardruna’s Einar Selvik. “Get it down you!” We’ve done some weird stuff in the name of journalism, from riding on Tommy Lee’s rollercoaster drumkit in front of thousands of Mötley Crüe fans to scaling a blizzard-blasted Austrian mountain to meet Powerwolf, but we’ve never stood in an East London cemetery on a freezing winter morning, with a blond-haired, bearded Viking gazing intensely at us, about to pop a raw stinging nettle we’ve just pulled up from the base of a gravestone into our mouth.

“Come on, get it down you,” repeats Einar, as the rolled-up leaf hovers near our mouth. A grin spreads across his face, almost like he’s taking some pleasure in our discomfort. And so, literally grasping the nettle, we pop it in. Down the hatch it goes. Well, actually it doesn’t. It gets stuck in our throat halfway down, leading to a fair bit of spluttering and dry heaving.

“How is it?” Einar enquires. In all honesty mate, we’ve had better.

Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park in Mile End, East London, was established as a graveyard in 1841 and is regarded as one of the ‘Magnificent Seven’, the nickname given to seven of the capital’s biggest and most historic cemeteries. It closed for burials in 1966, and today is run as a local nature reserve. It’s here, among the gravestones and leaves, that we’ve met Einar for a foraging expedition. As a man whose music and life are deeply entwined with the natural world, Einar isn’t a complete stranger to the concept of foraging.

“I have friends who do this sort of thing all the time,” he says. “Certain things in certain seasons are good to gather from the forest. I’m a novice, but I appreciate people creating awareness about how to use nature, and be part of nature, rather than just buying your groceries in the store.”

We’ve been joined by Ken, one of the park’s managers and a foliage expert. Ken leads around 40 foraging tours every year, ranging from the beginners’ tour we’ll be doing today to one that ends with him making a pizza using whatever he finds growing among the graves, cooking it over an open fire. Any doubts about the riskiness of eating plants pulled straight from the ground are eased when Ken informs us he once won an episode of Come Dine With Me using a menu of foraged food. Einar looks impressed.

“People like this, they actually make the world a better place just by having people touch plants,” he says, referring to Ken. “Touch soil, touch the ground, be around negative ions. It does something to your state of mind. It calms you.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Einar formed Wardruna in 2003 while he was still a member of Norwegian black metal band Gorgoroth, with the intention of creating music steeped in and inspired by his homeland’s cultural traditions. Their journey has been like few others. They’ve gone from playing their first ever gig in front of a 1,300-year-old Viking ship in Oslo to an upcoming date headlining the Royal Albert Hall in London in March (something Einar says is both a surprise and an honour). Given they’re a band that largely eschews modernity, favouring dark, atmospheric folk played on traditional instruments, their popularity is surprising.

The success of artists such as Heilung – who also draw on traditional instrumentation, folk and history – can be linked to doors opened by Wardruna. Einar believes the bands have become popular because of people’s hunger to reconnect with nature, in a modern world that has lost touch with its roots.

“I think it’s only natural, because that’s what you see in everything in society,” he tells us. “If the pendulum swings too far to one side, it’s gonna start swinging back. You will get a counterculture movement against it.”

Which brings us back to why we’re here today. There has been a surge in interest in foraging over the last decade. Ken puts this down to it being “another way people can connect to nature. Being in parks is good for our wellbeing.” So here we are, wrapped up warm to keep out the winter cold, with a member of one of metal’s most unique bands, ready to seek out some of the most delicious plants nature has to offer, straight from the soil. So what do we do then, Ken?

“Firstly, just pick some of the plants growing around the gate behind you and have a taste,” he replies. Einar wastes no time in grabbing a handful and gobbling away on them like a goat that has skipped breakfast. “I’m getting watermelon,” he says.

“Yes, very good!” exclaims Ken. Off we go to the next area, where Ken instructs us to try a piece of the red valerian, which is growing from a nearby grave, which sounds pretty metal. Ken warns us that it is “very bitter”, but stick it in a soup or use it as garnish for a salad and it makes a great substitute for spinach or rocket. He’s not wrong. Einar agrees. His own foraging experiences usually only amount to the odd berry or herb that he finds on his walks, though nature in the broader sense is central to Wardruna’s philosophy.

“I know a lot of people think it’s about Vikings and shit, but it never was,” he says. “The music itself has a very animistic place of origin. It is about nature itself, or our relationship to it.”

Nature feeds into Wardruna’s new album, Birna. Following the release of 2021’s Kvitravn, Einar spent two years writing poetry in an attempt to figure out a direction and theme for a follow-up. Eventually, he came to the realisation that he was “sick and tired of human fetishisation and having to put humans at the centre of everything”, and decided that Wardruna’s next album should tell the story of a bear (‘Birna’ is the Old Norse for a female bear, or ‘she-bear’).

“I use the bear, or the she-bear more specifically, as a way of telling a story about the cyclic movements of nature,” he begins. “It doesn’t need all of these human experiences to tell the story. Wherever there are bears, there are so many traditions, folklore, star signs.”

Einar believes that Birna conveys its story in a “slightly less esoteric way, speaking more directly”, compared to previous Wardruna albums. Still, there are layers to the record, and the bear is used symbolically to illustrate broader points.

“What is it with the bear that makes it so prominent in people’s lives, apart from it being a big, beautiful animal?” he muses. “Of course, it mirrors the movement we see in nature. The seasons, the life, death and rebirth of Mother Nature, that’s what we see with the bear: hibernation. That’s what we see with the salmon swimming upstream in the river to the place they were born to spawn and die. That’s beautiful poetry. That is basically what I wanted to paint the picture of. These movements that we see and how they connect.”

Hearing Einar talk about the beauty and wonder of the natural world, while scrambling around in the dirt and pulling up greenery from graves, has given us a bit of courage to scoff down pretty much anything Ken points at. He tells us to chomp on some pansies and primroses (cheaper than spending a fortune on sugared ones from Waitrose). Then he gets us to shake some hummingbird nectar from a bush and lick it off our hands. We pull up something called the ‘root of honesty’ and chew on its aniseedy base. We pick some seeds from a weed and discover a taste like nutmeg. We add the best of it to our basket, which is filling up quite quickly, to be used for our smoothie later.

Unfortunately, under the increasing delusion that we’re the next Bear Grylls, we get a little too cocky. We stuff a mouthful of a plant delightfully named lady’s smock into our greedy faces before Ken can warn us that it’s a great substitute for wasabi. Eyes water, throat burns, it feels like our nasal hair is singeing off. Einar looks at us like the dozy tourist we are.

“The bear is seen as the teacher,” he says. “Native Americans followed the bear and copied what they ate.”

That’s all well and good, but there aren’t too many bears in London’s East End.

After an hour, we’ve picked up enough foliage, berries, seeds and leaves to create our smoothie, so we settle in the middle of the park to create it. Ken, a man who has spent his entire time with us extolling the virtue of all things organic, pulls out a bottle of apple juice and a battery-powered blender to get everything going. He pours in the juice, alongside our assorted foraged ingredients, before setting us to work, Hammer squeezing a lemon and Einar drizzling some syrup (shop-bought, FFS) into the mix.

The Wardruna man is tasked with churning the whole thing up, making sure he keeps his impressive beard out of the way of the blender. Once it’s ready, Ken pours each of us a cup of the rather luminous green liquid. Can we forage? The moment of truth has arrived.

“SKÅL!” barks Einar, before putting the cup to his lips. We join him, swigging down a hearty gulp of the juice, and, if we say so ourselves, it’s very nice. A fruity, thick beverage with a tangy and rich aftertaste.

“It is nice actually, you’ve done very well,” he nods – high praise from a bloke who once won Come Dine With Me. Einar clearly agrees, going in for a second cup after polishing off the first one in record time.

“Nature creates culture,” he says, swallowing another mouthful. “When you go into older parts of our culture, you see that it’s sprung out of nature. That is why I believe a lot of these things still speak to us, why they are still relevant, why many of these traditions don’t belong in a museum. It resonates there because it’s relevant still, because it’s born out of the very ground we still walk on.”

Smoothies finished, we head back through the park, taking in the wildlife as we stroll. Einar tells us how he walks his dog for miles every day, which is when the majority of his ideas and inspirations for the art he makes come to him.

“It is medicine and it’s simple maths,” he says. “Just seeing the horizon, seeing and hearing birds – what it does to you, how it calms you.”

That calmness is evident when you meet Einar in person. It’s rare for a musician to be as present as he is. Rather than worrying about success or grand plans, he seems accepting of whatever the future may hold.

“Plans for the future?” he says with a snort, as we walk back to civilisation. “It’s not important. It doesn’t have to be this idea that everything has to grow, that everything needs to become bigger than what it is. For me, I’m so grateful for these opportunities. I think that’s the premise for growth – to be happy where you are and grateful where you are. It’s not something I or any of the other people involved take for granted, the fact that it speaks to people on a different level, not only through their ears. I enjoy being able to swipe the phones out of people’s hands, metaphorically speaking.”

Living in the moment, enjoying the natural world and creating art out of it? We’ll drink a foraged smoothie to that.

Birna is out now via Music For Nations / Sony. Wardruna's UK tour starts in Liverpool on March 17. The band also play ArcTanGent and Fire In The Mountains this summer. For the full list of tour dates, visit their official website.

Stephen joined the Louder team as a co-host of the Metal Hammer Podcast in late 2011, eventually becoming a regular contributor to the magazine. He has since written hundreds of articles for Metal Hammer, Classic Rock and Louder, specialising in punk, hardcore and 90s metal. He also presents the Trve. Cvlt. Pop! podcast with Gaz Jones and makes regular appearances on the Bangers And Most podcast.