It was early evening on Sunday, February 21, 1993 when the balloon went up. To the majority of people listening to Radio 1’s weekly chart rundown, the name Rage Against The Machine meant nothing. Why would it? A brand new band mixing metal and hip hop like no one had done before, they’d yet to make an impact outside of the nation’s rock clubs or the stereos of the more clued-in metal fan.

And so, when presenter Bruno Brookes cheerfully announced that their new single, Killing In The Name, had entered the charts at No.27 and cued the song up, neither he nor several million listeners knew what was about to happen.

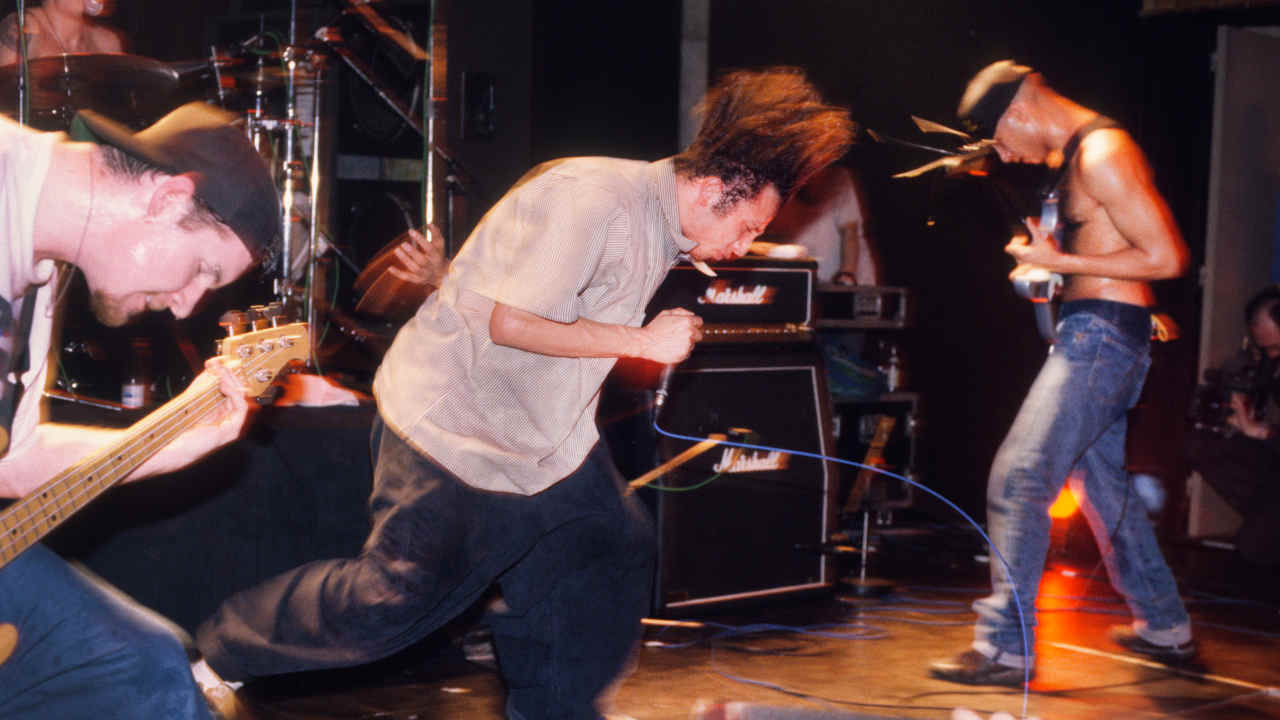

The song started with a coiled guitar and tense bassline, as some guy rapped about the American police force’s inherent racism with palpable vitriol in his voice: ‘Some of those who work forces are the same who burn crosses.’ Then – boom! – the whole thing suddenly erupted. Over guitars that sounded like a thousand police sirens wailing all at once, the line ‘Fuck you I won’t do what you tell me!’ blasted out of radio speakers everywhere, not just once, not twice, but 16 times. And then, suddenly, it reached its gloriously profane crescendo with one word hurled out with all the anger and pain that could possibly be mustered: ‘MOTHERFUCKER!’

Understandably, the snafu prompted a deluge of complaints to the BBC from offended listeners. Bruno Brookes, who was unaware that an unedited version of the song had accidentally been aired, was suspended for a week and almost lost his job. In just three and a half minutes, a group of political agitators from Los Angeles had detonated an incendiary device live on the airwaves.

“We knew the band’s politics were radical,” says guitarist Tom Morello today. “And that the band’s music was a radical combination of styles. But we didn’t think it was going to matter, ’cos no one was ever going to hear it.”

But people did hear it, in their millions. Rage Against The Machine were about to start a four-man revolution.

More than a quarter of a century after it exploded like a car bomb under the hood of mainstream culture, Rage Against The Machine has lost none of its power, impact or provocative fervour. It was the sound of Public Enemy yoked to Black Flag, of Dr Martin Luther King and Malcolm X set to a soundtrack of cutting-edge rap-metal.

Rage arrived as the wilfully shallow, MTV-driven rock scene of the 1980s was flat on the canvas with bluebirds fluttering around its head, laid out by the emergent grunge movement. In America, a new generation of hip hop bands was providing a vital social commentary, marrying the gritty reality of the streets with the violent glamour of a Hollywood crime blockbuster. All this was happening against a backdrop of global turmoil, racial tension and the threat of war in the Middle East. In hindsight, their timing was perfect.

In reality, it was purely accidental. Vocalist Zack de la Rocha, guitarist Tom Morello, bassist Timmy C (aka Tim Commerford) and drummer Brad Wilk had been in various low-level LA bands, including hardcore firebrands Inside Out (Zack) and Lock Up (Tom, who played on their sole album, the unfortunately titled Something Bitchin’ This Way Comes).

“I had been in a band that had a record deal, I had already had my grab at the brass ring,” says Tom. “The band got dropped and I was 26 years old, and I thought that was it. I thought, ‘If I’m not going to be a rock star, or make albums, I’m at least going to play music that I believe in 100%.’ And I was fortunate to meet three people who felt very similarly.”

The four were brought together by various mutual friends, though Zack and Tim had known each other since childhood. Zack and Tom came from similarly radical backgrounds – Zack was the son of Mexican-American political artist Robert de la Rocha, Tom was the son of a white American activist mother and a Kenyan diplomat father. Growing up, both had experienced racism first hand, and bonded over their hard-left political views – views that would shape Rage from the off.

“I wanted to ensure the protection of this band’s integrity,” Zack told journalist Ben Myers in 1999. “Our words had to be backed up by actions, because we’re dealing with this huge, monstrous pop culture that has a tendency to suck everything that is culturally resistant to it into it in order to pacify it and make it non-threatening.”

Ironically, for a band who would go on to become one of the most successful of the 1990s, Rage Against The Machine saw their very existence as limiting what they could achieve.

“We began with zero commercial ambition,” says Tom. “I didn’t think we’d be able to book a gig in a club, let alone get a record deal. There was no market for multi-racial, neo-Marxist rap-metal punk rock bands. That didn’t exist. So we made this music that was just 100% authentic, it was 100% what we felt like playing. We had no expectations.”

Still, it was clear to the members of Rage from the start that they were onto something unique. Brad Wilk can vividly recollect the band’s very first rehearsal.

“More than anything, I remember this connection and movement and momentum that was happening in the room,” he says. “Something clicked. I played so well with Tim and Tom, and then we had Zack, who was a bolt of lightning, flying off my kick drum and was in it for real. There was something really special about what we were doing. We weren’t analysing it or putting our fingers on it yet. It was just an intense moment for us all. We saw the very beginning of the potential we could have.”

Like so many Californian bands before them, Rage’s first gig took place not at a club but at a party, in Huntington Beach, in the sprawling suburb of Orange County, south of Los Angeles.

“It was a party in a house, and the place felt electric,” says Tim Commerford. “A lot of our songs didn’t even have vocals at that time. In fact, we played a version of Killing In The Name that was just the music – he hadn’t got the vocals done. You could feel the electricity. It felt like holding on to a fucking live wire. That’s what it was: a live wire. And it kept getting more and more live.”

Collectively, Rage were fans of hip hop, and Tom recalls the band’s early days being sound- tracked by the likes of Public Enemy and Cypress Hill. But while hip hop provided a big steer for the band, it wasn’t their sole influence. All four had grown up on guitar music ranging from 70s rock and 80s metal to punk.

“Our histories run deep, that’s why we were the band we were,” says Brad. “We didn’t just listen to hip hop, we listened to all kinds of things, from Black Sabbath to Led Zeppelin to Minor Threat and the Sex Pistols. When we were getting together, we agreed that we wanted our record to sound somewhere between Ice Cube’s AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted and Led Zeppelin’s Houses Of The Holy.”

In March, Rage embarked on their first proper tour as openers for Public Enemy. Thanks to the controversies whipped up by the US media around ‘gangsta rap’ acts such as NWA and Ice-T, mainstream America had a poisonous – read: virulently racist – relationship with hip hop, and trouble was never far away. It was the perfect environment for Rage Against The Machine.

“The tour was a needlessly controversial one,” says Tom. “At the time, rap was considered a dangerous endeavour, and the police sometimes outnumbered the audience at these shows. They tried to shut several down, filed injunctions – none of which were successful, I might add. We were playing these colleges, and the audience would be 100% white fraternity boys and sorority girls, passing through five levels of metal detectors and pat-downs. I think the cops were afraid that we were going to be bussing in Bloods and Crips to the show. There was an air of hysteria.”

Today, the guitarist still expresses bafflement that anyone at all would want to take a chance on Rage Against Their Machine and their political message, let alone a corporate record company. But their 12-track demo tape found its way into the hands of Michael Goldstone, the Epic Records A&R hotshot who’d previously signed Pearl Jam.

“Our only goal was to make music for ourselves and to make our own record – a cassette tape, an elaborate demo tape of the 12 songs we had written,” says Tom. “That was our entire goal. We never thought we’d play a show. We never thought we’d make a record.”

Garth Richardson was a young Canadian studio engineer whose biggest credit came on an album by hair metal B-listers White Lion. But he was young and hungry, and when Epic asked his boss, producer Michael Wagener, who should work on the debut album by this hot new rap-metal band they had signed, he was an obvious choice.

“I got the demo tape and went, ‘Holy shit.’ There was nothing else like it,” he recalls. “I went over to see them play in their jam space. I think they played me four songs, and I was blown away, to the point where I couldn’t talk afterwards, because my stutter was so bad. I was like, ‘Are you fucking kidding me – I’m going to be doing this band?’ It was their power, and also what Zack was saying. It was so fresh and so new.”

Rage began recording their debut album with Garth in March 1992. Seven of the 12 tracks from the demo tape, including Killing In The Name, Bomb Track and Bullet In The Head, would appear on the album.

“The songs were probably about 85 to 90% there,” remembers Garth. We made a few changes, mostly lyrically. Literally, somebody just had to capture them.”

To achieve this, the producer brought in a full concert PA system to get the full impact of the band’s live firepower. This was undiluted Rage – though sometimes it created unforeseen problems.

“The problem is that sometimes Zack’s voice went,” says Garth. “He was working it so hard. The end of Freedom, where he’s screaming, ‘Freedom!’, that’s just one take. Every time he sang, he gave it his all. Anybody that wanted him to hold back, he was, like, ‘No, fuck off, leave me alone.’”

Given the incendiary lyrical subject matter, there was surprisingly little input from Epic. They seemed to learn their lesson after suggesting the band remove the line ‘Now you’re under control’ from Killing In The Name. “There was a big conversation about that,” remembers Garth. “And the band just said, ‘Fuck you, that part stays.’”

Killing In The Name would be the song that broke the band in the UK. For six months, it soundtracked every rock club in the country, its impassioned call-to-arms galvanising dancefloors of people out to party. Yet, like so many of the great songs, it came about by accident.

“I remember coming up with that riff,” says Tom. “I was giving guitar lessons at the time, and I was teaching some Hollywood rock musician how to do drop-D tuning. In the midst of showing him, I came up with that riff. I said, ‘Hold on a second’, and I recorded it on my little cassette recorder to bring into the rehearsal the next day, never realising that it would be the genesis of a song that would have that lasting impact.”

In April 1992, a series of riots erupted in Los Angeles when four white policemen were acquitted of beating African-American motorist Rodney King, despite the assault being filmed by a witness standing on his balcony. For America, it was a moment of chaos. For Rage Against The Machine, who had already recorded their debut album and would release it in November, the timing was unfortunately convenient.

“All of those songs were written prior to the Rodney King riots,” says Tom. “In some ways the record was prescient, in that it saw this maelstrom of racial strife and imperialist war on the horizon. When the record hit, it was a fertile field for us to have the ear of audiences around the world.”

Rage were proudly revolutionary – too revolutionary for America, who were slow to catch on. Britain was a different matter, as Bruno Brookes’ unfortunate Radio 1 mishap proved.

“The UK was the first place people lost their minds over this music,” says Tom. “One of the principal reasons was that there were more lax lyrical censorship laws on your MTV and radio. We never edited the curse words out of songs, so people in the United States couldn’t even hear them on MTV, they couldn’t hear them on radio. And secondly, people over there were surprised to hear an American band that had a view of America that was similar to Europe’s view of America.”

From that small spark, a conflagration began to spread, as word about Rage Against The Machine grew. Their snowballing success had the desired effect, as a generation – or at least sections of it – began to wake up to the messages they were delivering through the bullhorn of their songs. Musically, too, they dragged the dormant rap-metal movement that had briefly flared up in the late 1980s back out of its stupor (in Bakersfield, California, the members of a brand new band named Korn were certainly paying attention to what Rage were doing).

Plus, society was changing fast in the early 90s. While sexism, racism and homophobia were still unfortunately prevalent, there was growing opposition to such outdated outlooks. Rage Against The Machine took it several steps further, crediting Black Panthers founder Huey Newton and Provisional IRA hunger striker Bobby Sands on the credits list to their album – a contentious move on both sides of the Atlantic. The sleeve itself featured a 1963 picture of Vietnamese monk Thich Quang Duc setting himself on fire in protest of his government’s oppression of Buddhism. It was the ultimate visual representation of protest.

“My heroes were not guys in rock bands,” says Tom. “They were revolutionaries who were fighting to change the world. It looked like we were going to have an opportunity to get in that arena. This was an incredible opportunity to engage the planet – not just with our music, but with our ideas.”

The success of Rage Against The Machine took everyone by surprise, not least Rage Against The Machine. They rapidly went from being the outcasts of the Hollywood scene to a lightning rod for the alt-rock movement. Rather than blunting their political edge, success only sharpened it – most famously in 1993, when they took to the stage at a Lollapallooza festival show in Philadelphia naked, apart from gaffa tape over their mouths, as a protest against censorship.

But the pressure-cooker environment that comes with being in a revolutionary left-wing band eventually took its toll. Tensions between the bandmembers grew, and Rage split up in 2000 after just three studio albums. They have sporadically reformed since – most famously for a one-off gig in London’s Finsbury Park, after a fan-led campaign saw a reissued Killing In The Name trounce the Simon Cowell-backed X-Factor winner Joe McElderry to the 2009 Christmas No.1.

More than 25 years after it was released, Rage’s debut remains a landmark – the point where rap and metal truly came together to deliver a body-blow to the status quo.

“Human strife has not changed. Racism has not changed. Things have actually gone backwards,” says Garth Richardson. “Rage Against The Machine wrote an incredible record that was current – and it will be time and time and time again.”