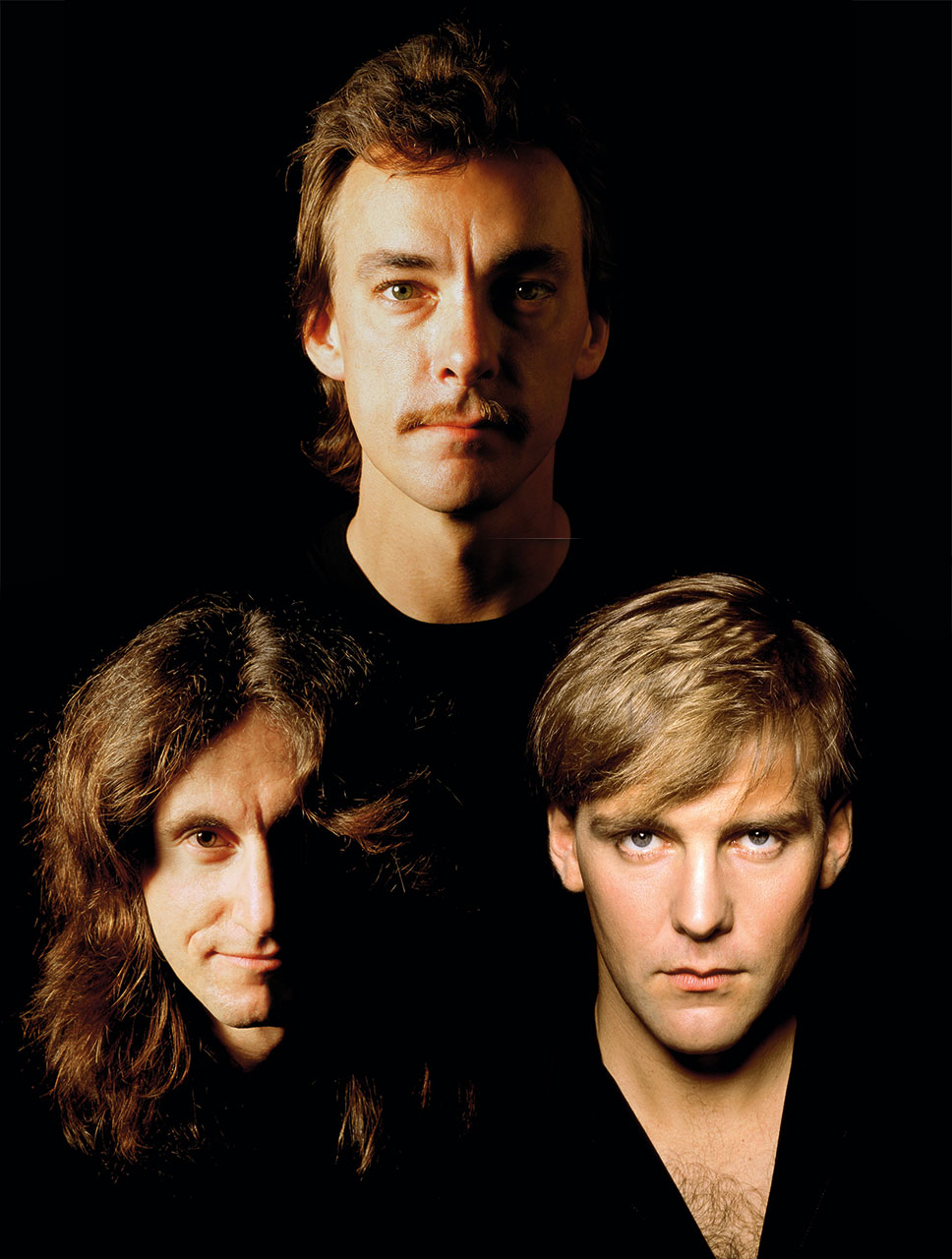

It’s the spring of 1982 and Rush are facing arguably their biggest challenge yet. Thanks to a more radio-friendly format and the continued integration of keyboard technology, the previous year’s Moving Pictures was by far the biggest seller of the Canadian trio’s eight-album career. Now it’s time for them to do it again, but for minds as inventive as those of bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson and drummer Neil Peart, the notion of self-replication is a complete non-starter.

“After the success of Moving Pictures we could’ve done anything we liked,” observes Lifeson, “and in Rush’s world, that usually means it’s time to change.”

The band dived headlong into a world swamped in keyboards and the very latest in electronic instrumentation. The ensuing sessions were to prove troublesome and their results not only divided their fanbase, but they also terminated a long and fruitful relationship with Terry Brown, the co-producer of all their LPs since 1975’s Fly By Night. Potentially more damaging still, the album concerned (later titled Signals) was the first of a sequence to alienate Alex Lifeson, whose contribution dwindled – the guitar certainly became less of a lead instrument – as layer upon layer of sequencers were daubed upon the trio’s aural canvas.

Today Lifeson is in London where, 24 hours from now, he will be presented with a Spirit Of Prog gong by Rick Wakeman on behalf of his bandmates at the Classic Rock Awards. Rush still make records and tour, and as every reader of this magazine knows, have flourished in the new millennium.

More than three decades later, Lifeson can look back at the events of 1982 with some detachment. This suggests that he’s either an extremely fine actor, or that the passing of so many years has softened the recollection of what must have been an extremely frustrating time for him.

“I agree with the consensus that Signals is among our most important and interesting records,” muses the guitarist, scrutinising the vinyl sleeve that Prog has brought along in the hope of triggering an extra memory or two. “But,” he adds, almost lost in a moment of quiet contemplation, “for obvious reasons I have mixed memories of that record.”

Rush actually began the preparation of material for Signals during their Moving Pictures tour. “Geddy and I had some of Subdivisions, and we’d worked on Chemistry over at his place,” relates Lifeson. “I had a little amp in the shape of a transistor radio with a tiny speaker which we put into a guitar case – that was our rather primitive recording technique.”

The band headed to Lake Windermere in the north of Ontario to fine-tune their ideas. Lifeson remembers with a shiver: “It was a very cold, snowy winter. The snow was piled up everywhere and we ended up staying in this deserted summer lodge.”

When Prog suggests that it all sounds a little like Stanley Kubrick’s iconic celluloid edition of the Stephen King novel The Shining, Lifeson beams in agreement. “That’s exactly how it was. There was one room that we converted into a studio/rehearsal area, and we began working on the material we’d brought with us.”

However, in contrast to The Shining, none of the group encountered any ghosts, lost the plot or began wielding axes and whacking them into doors. “I remember it as a very enjoyable time,” smiles Alex, before volunteering: “It was only when we began recording the songs that things became a little more difficult. That was the start of our wanderlust. It dawned on us that we wanted to try new ideas; maybe work with different people. It was an unsettling time.”

In April 1982, Rush, Brown and engineer Paul Northfield decamped to Le Studio at Morin-Heights for a four-month stay. John Wetton once told this writer that Asia suffered a near-fatal case of cabin fever while recording their Alpha album there the following year – the place is getting on for 60 miles outside Montreal, after all – but Rush relished the facility’s remoteness.

“We’re Canadians – we’re not afraid of snow!” Lifeson exclaims. “We loved being at Morin-Heights. Twice or three times a week we’d drive to a small town down the road and have dinner together. We’d put up a net and play volleyball after the sessions, and of course there was lots and lots of lubrication.”

From the snappier approach of New World Man, which became their biggest US hit single, to the more audacious The Weapon (Part II Of Fear), the material the band had accrued was rich in variety and quality.

“Subdivisions was such a strong song – a real marker for us,” Lifeson says. “We brought back Analog Kid on our last tour and the mix of guitar and keyboards makes it great fun to play live. I love the chordal progression of Chemistry, but with retrospect it’s a little disjointed, and getting Digital Man to sound the way it did was like pulling teeth.”

Perhaps surprisingly, Geddy Lee dismissed Countdown as “a pretty poor song” in 1992. “I love that one, actually,” responds Lifeson, “but I know what he’s saying: we could’ve spent more time on it.”

Lee later expressed the viewpoint that Signals was “a difficult album to make, and it spelled the end of our relationship with Terry Brown”, a statement Lifeson echoes. “With the possible exception of Moving Pictures, which almost fell into place, they’re all difficult to make,” he laughs, “but if I told you the creation of Signals was completely smooth then I would be lying.”

But the straw that broke the camel’s back was the reggae-ish section of Digital Man, which, so the story goes, Terry Brown hated so much that he at first refused to record it. “You know what? I don’t remember that being the case,” responds Lifeson diplomatically. “But Terry was definitely afraid that we were moving away from being a rock band, taking too much influence from other bands like The Police. And he really wasn’t keen on Neil’s use of electronic drums.”

Rush, for their part, were keen to experiment with all of the new hardware that was becoming available. “All three of us we were unanimous in that desire,” clarifies Lifeson. “That’s what Rush is – we’re always looking to try something different, or to head in a new direction.”

The problem with Signals, from Lifeson’s viewpoint at least, lay not with the songs but in an irregular production. “In a couple of key places there was too much emphasis placed on the keyboards,” he explains. “The mix of Subdivisions has always been a disappointment for me. I recall leaning over to push up the faders [to increase the guitar levels in the mix] and Terry would smile and push them back down again.”

Lifeson tolerated this situation for a while, ‘taking one for the team’ in today’s parlance – though Lee later related how the normally placid Lifeson returned to the studio with fresh perspective following a few days away, storming into the control room with the statement: “There’s not enough guitar on this record for Chrissakes!”

“The language was probably more colourful than that,” guffaws Lifeson at the memory. “But look, a band operates on consensus. Everybody else felt we were going in the right direction. To my way of thinking there was an imbalance, but I have no regrets.

“The song Digital Man, for instance… there’s no problem with that. But we had so much trouble getting the feel right. The direction was lacking, and that’s when you need a strong producer.”

Geddy Lee once observed: “We were bored of doing things the same old way. We should probably have changed producers instead of changing the internal balance of the band.”

“That’s what it all boils down to,” agrees Lifeson now. “We were not getting the kind of direction and guidance that we needed.”

The split with Brown was amicable (indeed, the credits of the band’s next, self-produced album, Grace Under Pressure, included the tribute: “Et toujours notre bon vieil ami – Broon”), but Lifeson admits it was a wrench.

“For sure,” he nods enthusiastically. “Terry had been a big part of this band. Besides the actual production, he was there for all of the writing sessions and the arrangements, so his exit left a big hole. Deep down inside, though, it was time.”

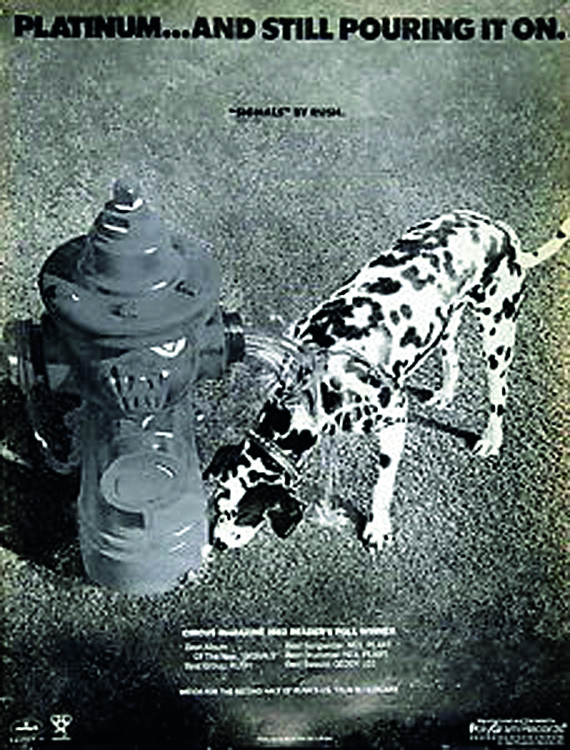

Released in September 1982, Signals topped the charts and went platinum in the band’s homeland, though sales didn’t match the stellar performance of Moving Pictures. Its more user-friendly contents served to polarise the opinions of diehard Rush fans. “Some people love it, others hate it,” nods Lifeson in agreement. “That’s inevitable.”

Lifeson is now able to sit and listen to Signals from start to finish without feeling pangs of disappointment. Would the same statement have applied when the album was fresh from the printing press?

“It’s a good question,” he smiles, “and there were times when I might’ve felt [reservations] at certain points back then, but now I’m very proud of it.”

As New World Man became a surprise hit, the band’s facelift rubbed off on other groups, many of whom suddenly began adding keyboards to their sound. Formed three years later, the keys-dominated Dream Theater have never been shy of admitting the influence of Rush. The prominence of keyboards only escalated over Rush’s next few records as their productions became ever more slick and pristine, until a Rupert Hine-helmed return to basics with Presto in 1989. It could be claimed that Signals and the records Rush made with Peter Collins (1985’s Power Windows, and Hold Your Fire in ’87) helped to pioneer the way that progressive hard rock would develop over the next decade.

“That’s flattering to hear but we’ve always tried to move on quickly to the next thing,” beams Lifeson, adding with his usual tact: “When another band follows in your footsteps, it’s always an incredible compliment.”

As stated, material from Signals and its keyboard-cloaked successors figured highly in Rush’s 2013 setlist, as documented on the Clockwork Angels Tour DVD. Acknowledging the fact that this decision wasn’t universally popular among some of their fans, the guitarist can offer no explanation for the fact. “It just seemed like a good idea at the time,” he smirks. “We’re contrary like that.”

Talking of which, expect Rush to adopt a low profile in 2014 – despite the fact it marks the 40th anniversary of their existence as a band.

“So we’ll celebrate the 41st anniversary in 2015 instead,” Lifeson responds casually. “For the last dozen years we’ve really burned the candle at both ends. It’s hard to play for three hours, travel and do 80 shows, plus interviews and stuff. We’re really going to try not to work for the entire year in 2014. We need and deserve a rest.”

This feature originally appeared in issue 43 of Prog Magazine.