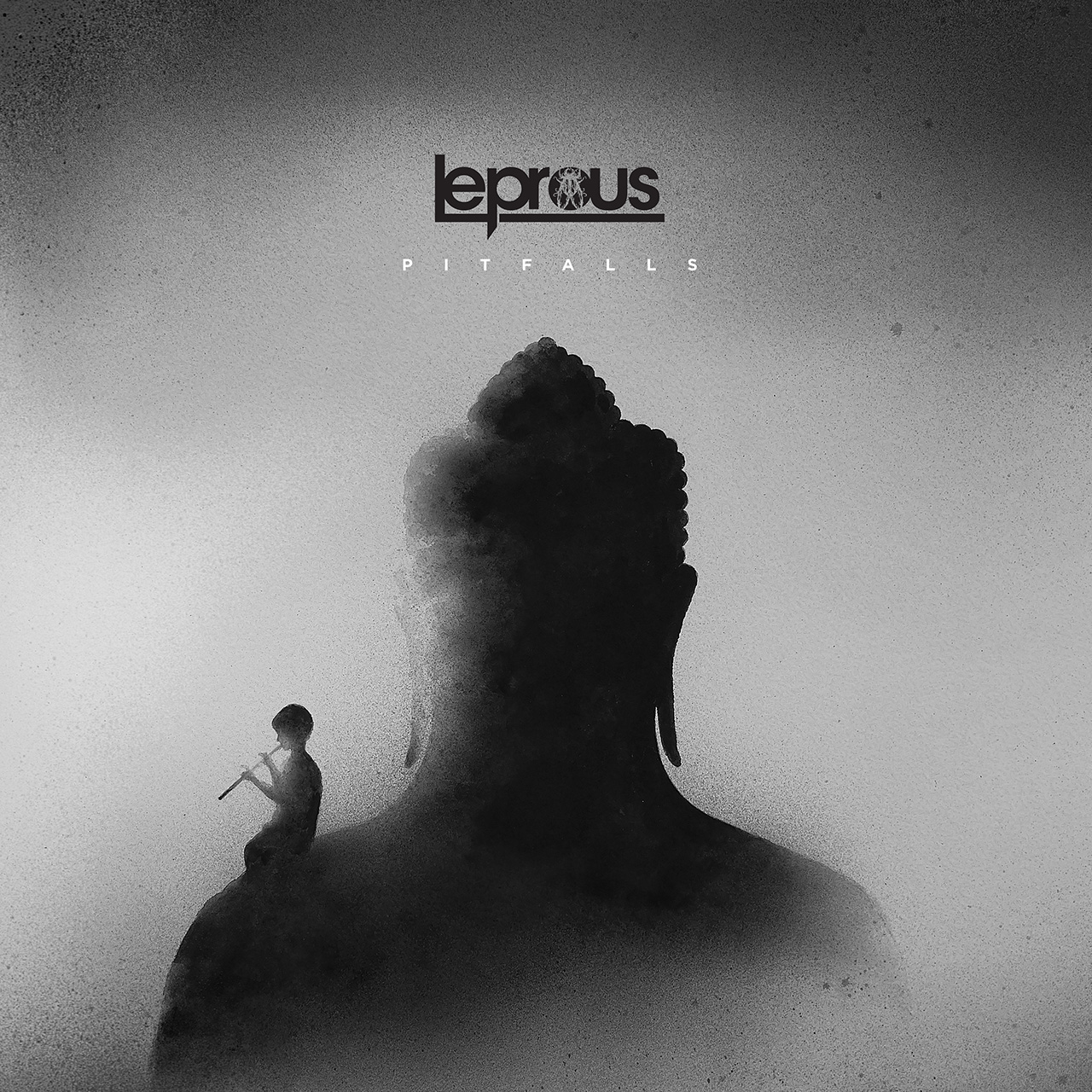

Leprous’ sixth studio album, Pitfalls upped the melancholic atmospherics, the cinematic drama and the prog. In 2019 main songwriter Einar Solberg explained to Prog how the Norwegians did it.

Einar Solberg didn’t intend to write a long song. He doesn’t even like them. Yet, sitting in a comfortable chair by the fire, laptop perched on his legs, the Leprous singer and main songwriter began composing what became the 11-minute, avant-garde epic The Sky Is Red. On it, his high-pitched wails drift precariously over complex percussion, as the music builds towards clipped choral bursts which sound like doomed souls protesting in Hell. Hearing it, an outsider might conclude that Leprous had decided to go full prog.

“I was trying to do the opposite, actually, but it seems there’s still too much in my blood!” Solberg laughs. “Because I don’t like long songs, even. I think they’re usually filled with way too much stuff that could have been thrown out. I thought The Sky Is Red sucked in the beginning because it was too weird for what I was aiming at.”

He played it to his mother, who expressed nothing but encouragement. His bandmates liked it, too. Eventually, Solberg himself grew attached to his experimental composition, especially the idea of bringing in choral singers.

“When I told the others, they were like: ‘Ahhh, oh yeah, I like it, even though we have a budget,’” he remembers, adopting the tone of someone who’s cautious about bending the rules. “And I was like: ‘Yeah, I know. But I have a vision!’”

The song closes Pitfalls, the new Leprous album that’s bursting with Solberg’s visions. Most of its tracks are in the four-to-seven-minute mark, as usual, and are led by his distinctive, operatic voice, which hits glass-shattering crescendos with glorious ease. It’s also a stylistic shift away from 2017’s Malina, leaving behind some of their harder-hitting, prog metal tendencies and upping the melancholic atmospherics and cinematic drama. Again, this was not a deliberate decision, but the result of Solberg’s spontaneous creativity.

“It’s not a conscious process for me usually, because I’m a very intuitive person,” he reveals. “I act on emotions and sudden impulses and feelings; I’m not a careful planner. I’ve changed a lot during the years and developed as a person, and so have the rest of the band; we get new views on things. We were just aiming to do a new album and see how it was, you know? And obviously we never want to make the same piece of work twice. You want to go where it’s leading you and not dwell too much on the past.”

Solberg recently moved from Norway’s capital Oslo to the town of Kongsberg,

50 miles west. He chose the area because it’s still close enough to the city’s airport, is near his family, and is surrounded by nature. Today he’s just got back from a cold, rainy run through the streets, but when he’s feeling energetic enough he often follows the forest trails uphill. It’s only a 30-minute drive from Notodden, where he started Leprous in 2001, but he describes the area as “too hillbilly” for him to live there.

Over the past 18 years, Leprous have steadily evolved across six albums. They started out as Norwegian multi-instrumentalist and singer Ihsahn’s backing band, before forging their own reputation free of any outside association. Following the release of Malina in 2017, they went on their most successful tour ever, selling out shows for the first time and finally going into profit. They toured Latin America, sub-headlined Prognosis in Eindhoven last March and headlined Tech-Fest in July.

When Solberg came home after the Malina tour, he felt “euphoric”, and began playing around with some song sketches, and came up with the skeleton for lead single Below. But the process soon stalled as he fell into a period of depression.

“A lot of bad things have happened in my past that I’ve never talked about publicly, but my strategy has always been to go full speed forward and keep distracted,” he explains. “It can work for many, many years and you can be reasonably happy. The problem is when you never deal with things, at some point it will catch up with you. Something can trigger it and, once you’re down, then it’s going to hit you hard.”

For Solberg, the trigger was his health, as some minor issues sent him spiralling into anxiety about death – “kind of hypochondriac stuff”, as he puts it today. Lacking energy and motivation, he found himself in a creative slump, unable to write. It took a couple of months before he could get back into it.

“You just keep on trying,” he says. “I’m not used to getting things very easily. Leprous’ career has been hard work from the beginning. We’ve been investing and losing so much money for years, and we try to just be patient. I should’ve just learned how to be patient, and to see that two months maybe feels long, but in your whole life it’s almost nothing. I try to kind of keep that [thought of]: ‘Okay, I will get back to it, I’m not going to lose my motivation permanently, it will come back.’ So it’s just a gradual thing. You get these sparks of light and you use them for something, and then the spark of light becomes bigger, and then when you start creating I think they can trigger even bigger sparks of light that you can use.”

Thankfully Solberg is now in a much better place, though these experiences are embedded in his music; on Below, he references childhood memories and fears buried in his mind. The second song he wrote for Pitfalls (technically the ninth, but he scrapped the ones in between) was the stunning centrepiece At The Bottom, a seven-minute declaration of pain via electronic pulses, deep bass, strings and spinetingling key changes. It’s one of the only songs where Solberg deliberately set out to disrupt conventional song structures, and he almost binned it because he couldn’t come up with a vocal line, until inspiration struck a year later on one of his runs, which he keeps up to maintain his mental and physical health.

“That was a super-slow process,” he recalls. “It wasn’t until a week before I was gonna sing it in the studio that I had it done. Some songs are more difficult to make vocal lines for, for some reason. You get hung up on some shitty vocal lines that you make, and you can’t get them out of your head. So I was just running, running, and suddenly that song came back on and a new melody came into my head. I think what happened was that suddenly I wasn’t over-analysing.”

The rest of the band were on board with the direction Pitfalls was taking, although drummer Baard Kolstad expressed some concerns. Anyone who’s familiar with him will know how extremely technically competent he is, and how his beats have become a big part of Leprous’ sound over the last three records.

“I remember in the beginning, Baard was a bit scared, because I only had electronic drum loops on every sketch,” Solberg recalls. “He liked it, but he was scared he would be replaced. I then explained to him: ‘No, no, no, don’t worry. I just don’t want to waste time programming drums when I know you’re going to do something different there anyway. On some songs, though, that electronic vibe was kind of cool to keep. But then we also sat together, so he could do something more that was made from us, and not a generic loop.

“I was incredibly impressed with the band and especially Baard. He’s such a virtuoso drummer, but he has shown so much maturity by being able to show restraint and to do what the song needs, and it’s not about showing off. I didn’t have to tell him, I said: ‘Do your thing.’ And ‘That’s very classy stuff’ was my first reaction. I think it takes a lot of confidence to have that ability to play the most technical stuff ever, but still do just what is needed for the song itself.”

Leprous recorded with returning producer David Castillo at his Ghost Ward Studios in Sweden, with Solberg working there from September until July. The nine songs on Pitfalls swoop and soar with confidence, dipping into rock, pop and jazz, untethered by rules and unrestrained emotionally. Solberg’s not sure if the band are prog, but he’s happy that the community has embraced them.

“For me, prog is too much about musicianship, technicality and complexity, and all this kind of stuff that doesn’t really matter to me,” he says. “So I think when we’re complex, it’s complex by accident a little bit! Our fans are really loyal and we appreciate them a lot, but we’re definitely not the typical prog band, because for us musicianship isn’t a super-important part of the whole thing, it’s more about feeling. If I want to be impressed, I’ll watch Usain Bolt running. If I want to listen to music, it’s because I want to feel something.”

When Leprous were Ihsahn’s backing band, they had to battle preconceptions that they were a black metal band. But with a ton of shows under their belt, and a sound that’s pushing up against the mainstream, Solberg reckons the majority of their fans “don’t even know about it”. Since Malina, Solberg has been aware that their reputation is growing rapidly, even if he’s reluctant to agree that they’re on the cusp of a breakthrough.

“Where is the definition of a breakthrough, though?” he asks. “I think we’re on the way to being one of the most streamed bands from Norway now in the rock genre. It’s definitely shooting up, so to speak. But it’s been very gradual for us, so I’m not expecting any super-sudden breakthrough. It’s been more of a kind of snowball effect, from what I can see. With every album, the snowball gets a bit bigger. Of course it’d be possible to get a breakthrough, but that would have to mean something like a commercial breakthrough, and I don’t think the industry works like that any more. But in the prog scene we’re definitely getting there.”

When Solberg talks about his achievements, there’s a down-to-earth modesty in his voice, as well as a hint of pride. He started Leprous when he was 16 and he’s now 34, so he has been doing it for more than half his life, dedicated from day one.

“Leprous meant as much to me back then as it means to me now,” he says. “It didn’t matter to me to play a few local shows a year. I was so enthusiastic about those shows, even if it was only 30 people. So it’s very important for me that music keeps on being my biggest passion. If I start doing music for other reasons, like money or glory, then I’ve kind of lost it, in my opinion.”

Judging by the originality of Pitfalls and the smile in his voice today, he’s nowhere near that yet.