For British rock bands in the early 1970s, a sneering, patronising review in US magazine Rolling Stone was considered something of a badge of honour.

In it, Led Zeppelin’s self-titled debut album was dismissed as “dull”, “redundant” and “prissy”. The “clubfooted” riffs on Deep Purple In Rock were seen as evidence that these “quiet nonentities” lacked “both expertise and intuition”. Black Sabbath’s first album was labelled “inane”, “wooden” and “plodding”, the band that became the most influential in the history of heavy metal written off as “Just like Cream! But worse.”

Rolling Stone’s most scathing notice, however, was about Uriah Heep’s debut album, 1970’s Very ’Eavy, Very ’Umble: “If this group makes it,” wrote one Melissa Mills, “I’ll have to commit suicide.”

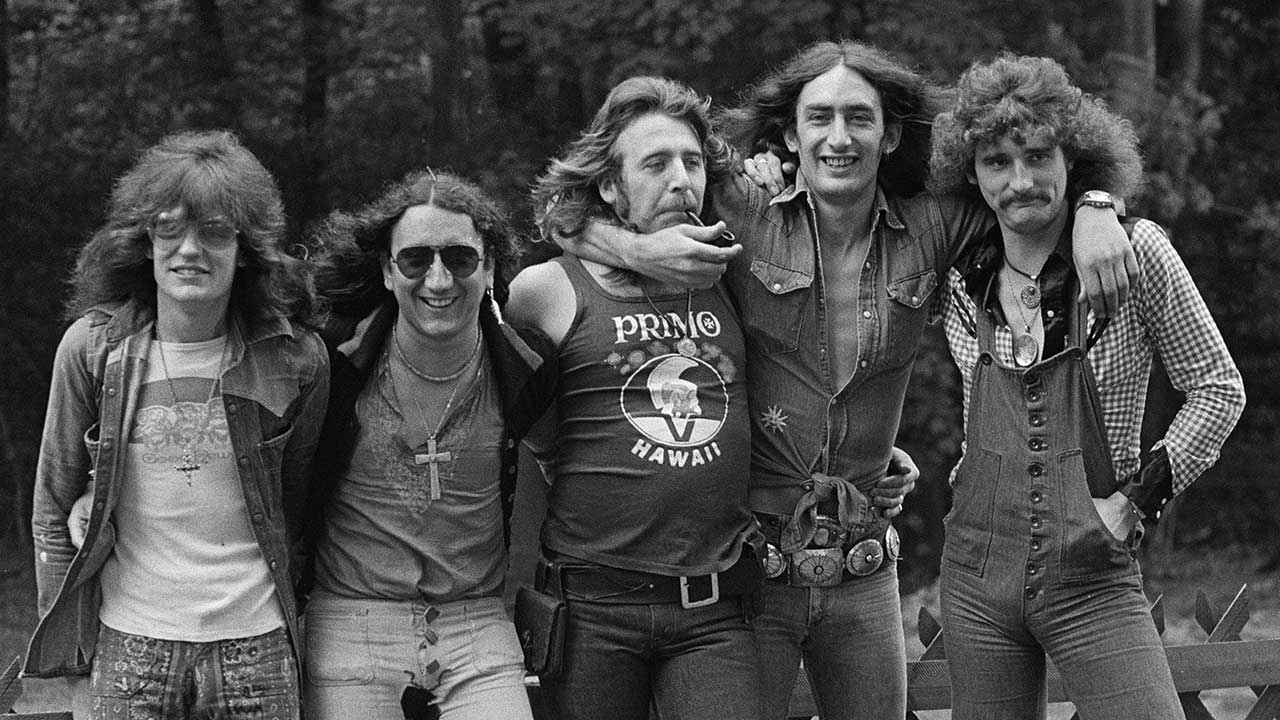

Today Uriah Heep guitarist Mick Box can afford to look back and laugh. A candidate for the most chipper man in rock’n’roll, the 73-year-old cheerfully admits that he’s “never been one to listen to critics too much”.

“It’s difficult to care about criticism about what your band is lacking when you’re being called back on stage for five encores every night,” he points out with a hearty chuckle.

Inspired by a love of The Kinks, the Small Faces, The Who and Johnny Kidd & The Pirates, Walthamstow-born Box formed his first band, The Stalkers, in the mid-60s while still a teenager. By the time Bobby Moore hoisted the Jules Rimet Trophy aloft at Wembley Stadium on the evening of July 30, 1966 when England won the World Cup, The Stalkers had become Spice.

At some point late in 1969 the band caught the attention of influential manager/producer/publisher Gerry Bron. It was at Bron’s insistence that the youngsters changed their name once more, to Uriah Heep, an ’umble, obsequious character in Charles Dickens’s 1850 novel David Copperfield.

Bron then installed the group in Hanwell Community Centre in West London to assemble songs for their debut album. Through the facility’s walls they could hear the Mk II line-up of Deep Purple prepping for what would be their In Rock album.

By their own admission, on their first three albums the young Uriah Heep were “just thrashing about trying to find a direction”. Their unfairly maligned Very ’Eavy, Very ’Umble album, mixing folk, blues, jazz and hard rock, was followed by two studio albums in 1971: the progressive rock-inclined Salisbury – on which multi-talented keyboard player Ken Hensley began to eclipse Box and frontman David Byron as the band’s main songwriter – and Look At Yourself, the first release on Gerry Bron’s new record label Bronze Records.

In between the two releases, on March 26, ’71 Uriah Heep played their first show in the US, supporting Three Dog Night, in front of 16,000 people at the State Fairground’s Coliseum in Indianapolis, Indiana. For the Londoners it was a first glimpse of the infinite possibilities of rock stardom.

“When we got there, and saw all the limos and groupies, it was mind-boggling for us,” Hensley said later.

“There was never a feeling of being overawed by it all,” Box insisted to Heep biographer Dave Ling. “We all felt that this is where we should be. The American audience loved us from the first minute onwards. Believe me, lots of champagne was cracked open on that first night.”

When the group returned to the US for the second time, in January 1972, they were booked to open for Deep Purple, their noisy neighbours from Hanwell Community Centre. Their gregarious guitarist, meanwhile, was taking advantage of his group’s burgeoning reputation by thumbing through local phone directories and placing calls to random young ladies, inviting them along to gigs and parties.

“You’d tell the bird you were in Uriah Heep, and next minute the hotel was full of women,” Box recalled cheerfully. But such a lifestyle wasn’t for everyone. On January 31, upon completing the final date of the Deep Purple tour, bassist Mark Clarke quit the band, having joined only four months previously.

“Mark jumped ship because he couldn’t deal with the stresses of the touring we were doing, which were excessive, I have to say,” Box says. “It was a mad, mad, mad time for us all. Mark felt that he just could not keep up with it, that he was going to have a full-on nervous breakdown if he stuck around any longer.”

Although Clarke’s time in the band was short, the ex-Colosseum bassist did make one lasting and significant contribution to Uriah Heep, writing a striking, harmonised middle eight for a new Ken Hensley composition titled The Wizard, based on a fantastical recurring dream he’d had every night for a week.

“I remember Ken playing The Wizard on an acoustic guitar in the back of our van,” says Box. “It was the first time I’d heard anyone play guitar with a drop-D tuning. He couldn’t find a middle eight, so Mark Clarke wrote that, and the whole song sounded so good to everyone. I think we all knew it was something special."

Gerry Bron, too, heard potential in Hensley’s whimsical power ballad. Ahead of their second visit to the US, Heep were rushed into Lansdowne Studios in Holland Park, where they tracked the song (and single B-side Why) in a matter of hours. Before the session ended, The Wizard’s semiacoustic intro was beefed up with the addition of an unusual instrument – the studio kettle.

“We were making a cup of tea, and had the studio door open, and as we were listening back to the intro of the song we heard the whistle, and thought: ‘Hang on!” Mick Box recalls. “We went into the kitchen, recorded the kettle whistle two or three times and got it re-tuned to a high C. That’s the note you hear at the beginning of the song.”

While Bronze Records readied The Wizard for an international release, Heep bedded in Mark Clarke’s replacement Gary Thain with a five-night stand at the Whiskey A Go Go club in Los Angeles in February ’72. New Zealander Thain had come from the Keef Hartley Band, and clicked instantly with Heep’s other new addition, drummer Lee Kerslake, who had joined just three months previously. The pair’s obvious chemistry, and superior musical ability, immediately elevated the whole band to a new level.

“Now we finally had a real steam engine of a rhythm section,” Box says, admiringly. “Having those two powerhouses behind us provided a wonderful foundation for the band. Lee was a fantastic drummer, and Gary would come up with these great bass lines that never got in the way of the melody of the song but always seemed to enhance it. It was an incredible knack. It was a real pleasure to work with the pair of them. Everything just clicked into place.”

In mid-March, back in England the quintet returned to Lansdowne Studios to complete work on their fourth album.

“Everyone was focused,” says Box. “We were recording in London, which was nice, and the chemistry in the band was bar none. There were no personality clashes, no factions fighting for different things, no diversions.”

“There was a magic in that combination of people that created so much energy and enthusiasm,” Ken Hensley later noted. “We all wanted the same thing, were all willing to make the same sacrifices to achieve it and we were all very committed.”

As he had done on Look At Yourself, keyboard player Hensley led the sessions, bringing five new songs to the table. And, as with The Wizard, the album’s foundation stone, the songs largely had fantasy themes. The heavy-grooving Rainbow Demon spoke of a rider on a crimson horse, ‘possessed by some distant calling’; the delicate Paradise told of a heavy-hearted young man’s quest for true love; its multi-part companion piece, the dramatic hymnal epic The Spell, featured heavenly choral vocals, a stunning Hensley slide guitar solo, and gloriously portentous lyrics: ‘You will never break the spell. I’ll summon all the fires of hell’. The spooky, organ-driven, Circle Of Hands, meanwhile, was inspired by a brush with the supernatural.

“It was born out of a séance we were invited to by some girls in Italy,” Box reveals. “It all got a bit out of hand, a bit freaky. These things start out as a bit of fun, then you start to get a bit uncomfortable, and then it’s: ‘Bloody hell, I’m getting out of here!’ That was the first and last time we tried to summon spirits of the dead. We were dabbling where we should never have dabbled.”

The down-to-earth guitarist brought rather more grounded tunes to the studio: the bluesy, Zeppelin-esque All My Life, the hard-riffing Poet’s Justice, originally conceived as an acoustic track, and the driving Traveller In Time. All three songs were fleshed out in jam sessions with David Byron and Lee Kerslake.

“I’d have riffs knocking around, and maybe a verse, and when I took them into rehearsals those two would jump on them and suddenly we’d have another song,” Box marvels. “They came together very quickly, as we were very attuned to one another. It was almost too good to be true. Someone would nip out to the shop, and come back to find another song written. It was such an easy album to record.”

“There was nothing between us and the music,” Hensley told the Classic Rock Revisited website in 2016. “This liberated my creativity. And the fact that FM radio in America was pioneering the musical freedom trend made it even more inspiring.”

For all five musicians, and Gerry Bron, Heep’s self-appointed sixth member, the choice of a single from the album was a no-brainer: everything about the rollicking Easy Livin’ screamed ‘radio hit’. Written by Hensley in just 15 minutes, it was a tongue-in-cheek reflection of outsider perceptions of the band’s lifestyle.

“It had excitement written all over it,” says Box. “I thought the guitar sound was fantastic, it was so up-front, and aggressive and pumping like mad. The title came from a conversation we had in the van. We were in the north of England, driving down to London to listen to some recordings in the studio before going to the airport to fly to America, and someone said: ‘This is easy living, isn’t it?’ as a joke, a piss-take. But it resonated with Ken. It wasn’t a song that we over-thought.”

With a sleeve featuring artwork by the noted fantasy artist Roger Dean, Demons And Wizards was released on May 19, 1972, and peaked at No.20 in the UK chart the following month.

Initial reviews were positive: “Demons And Wizards has got to be the party album of the year so far,” Rolling Stone raved. “They may have started out as a thoroughly dispensable neo-Creak & Blooze outfit, but at this point Uriah Heep are shaping up into one hell of a first-rate modern rock band.”

It was the August release of Easy Livin’ – singled out by Rolling Stone writer Mike Saunders as a “flat out fuzz-tone punk rocker” – that turned the album into a global smash. Although Easy Livin’ failed to chart in the UK, it became a Top-20 hit across mainland Europe, and peaked on Billboard’s Hot 100 at No.39 on September 23. By the end of October, Demons And Wizards had reached No.23 on the Billboard 200 album chart.

“Hearing the song on US radio was immense,” Box says. “But you had to get out there and work it. We started out touring in the Midwest, the strongest rock market, and let the music filter out to the coasts. Then things started moving very, very fast. A hit single is like a small boulder rolling down a hill, gathering moss, and by the time it gets to the bottom it’s huge. It wasn’t long before we were doing ten-thousand-seaters right across America, and had Lear jets and limos at every airport. It was an absolutely amazing time.”

But there was a darker side to the band’s US success. With tour posters promising that Demons And Wizards “performs mentalingus on you”, Heep began to encounter “freaky people” coming out of the woodwork at their shows. In a 1973 NME interview, David Byron related a tale of being visited in Detroit, the band’s biggest market, by the city’s messianic underground leader, Jaggers, a stick-thin, Mick Jagger-obsessed guy wearing a long black cloak and white face-paint.

“He came in and shut the door and said: ‘Lock it’,” Byron recalled. “He said: ‘You see, the thing is, the people think I’m dead. And that’s why I dress in black. If anybody asks if you’ve seen me, say you haven’t.’ It turned out he was a lunatic. And this goes on and on and on in every major town in America.

"These birds with cherry-red lipstick come up and say: ‘Hey man, you’re really cosmic. It’s so heavy. And I really dig it… I always listen to your message.’ Crap. All these weird birds got hold of our old ladies’ phone numbers and addresses, and they started doing all these ghostly trips when we’re away. We were getting so many weird letters that it was driving us round the bend. It just started to do us in.”

“It got very, very silly,” Box admits. “We got to the point where we had bodyguards outside each of our hotel rooms, particularly in the Midwest. It got heavy, and very hedonistic, totally decadent. All the stories you hear about being a successful rock band in America are all true. And I can’t tell you any of them! Ha ha! I enjoyed it for what it was, but I never felt like it would last forever at that level.”

The guitarist’s caution proved prescient. Before embarking on a two-month US tour scheduled to run from October 13 to December 17, the band were rushed into Lansdowne Studios to record a new studio album. Released in November, The Magician’s Birthday reached No.28 in the UK and No.31 in the US. But its short-term success came with long-term costs. Ken Hensley described the making of the album as“frustrating” and “the beginning of the end”, claiming that a number of his songs were unfinished, rush-released before being properly signed off. Mick Box too was unhappy with the pressure exerted on the band. Looking back, the unassuming guitarist lays the blame squarely at the feet of management.

“Doing The Magician’s Birthday that quickly was all about capitalising on the success of Demons And Wizards,” he reflects. “If you want my honest opinion, I think that was down to management greed. Gerry Bron was pushing us so hard that there was no attention to anyone’s personal life or health. It was ‘Go! Go! Go!’ I can understand an element of that, because when we first started off he put a lot of money in, taking out full-page ads in the music papers, buying us a lot of equipment, and putting us on a twenty pounds-a-week wage.

"So he did invest in us. But by the time we reached Demons And Wizards we’d paid him back tenfold, and he was still pushing for more, more, more. There were demands for another hit single, which got draining, as we always saw ourselves as an albums band. Also, as Ken was having great success with his songs, management singled him out and started only listening to what he had to say, which created animosity with the rest of us. And then the wheels started falling off.”

It is perhaps some measure of the high expectations raised by the success of Demons And Wizards that Uriah Heep are sometimes considered to be the ‘nearly men’ of British hard rock. It’s true that they never threatened to match the success of Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, Black Sabbath or Queen, and on a statistical level never again came as close to cracking the mainstream as they did with their fourth studio album. But 45 million worldwide album sales and a touring presence in 61 countries are hardly indicators of failure.

Unfailingly honest and unpretentious, Box can concede that, at points in their career, Uriah Heep “didn’t stay true to their platform”. But having racked up nine UK Top 40 albums, and been on the Billboard 200 no fewer than 15 times, his band have enjoyed career highs that precious few modern rock bands could ever aspire to. Crucially, Box is still loving life in the band he began writing for 50 years ago.

“We’ve got a great foundation,” he says cheerfully, “with a history and songs that have stood the test of time, and we’re still writing new music which the fans are enjoying as much as ever.”

However, he’s not unaware of the esteem in which Demons And Wizards is still held, as was evidenced when Uriah Heep performed the album in full in the US for its fortieth anniversary. But it’s an album holding bitter-sweet memories for the guitarist, not least because four of the musicians who played on it – David Byron, Gary Thain, Lee Kerslake and Ken Hensley – are no longer alive. Singer Bryon passed away in 1985 due to alcohol-related health issues, bassist Thain succumbed to a heroin overdose 10 years earlier, in September 2020 Kerslake lost his battle with prostate cancer, and most recently Hensley passed away (in November 2020) following a short illness.

Roger Dean’s cover artwork still hangs in the front room of Box’s London home, and he’s signed enough copies of the album over the years to be aware of its significance to fans.

“There’s something on every Uriah Heep album that I can look back on with fondness,” he says, “but Demons And Wizards means a lot to me. Where we were as a unit, creatively, it was the band at its height, with that line-up. Listening back to the album through the speakers at Lansdowne back in 1972, we felt like we had something special, but that was just within our inner circle. After that you just hope that it might take on a life of its own and become successful. Which, to our immense gratitude, it did."

“I know how much that music means so much to so many different people, and it’s humbling,” the guitarist continues. “With the Roger Dean cover, it was the first time that the music and the lyrics and the artwork were intrinsically linked, and I think that contributed to its success. But then, funnily enough, it was Easy Livin’, with no mythical lyrics whatsoever, which was the hit that opened up the world stage to us.

"If that song taught us anything, it’s that sometimes in this business it’s best not to over-think."