On Monday night, five days before the first of Led Zeppelin’s two shows at Knebworth, there were some 30 or so fans staked out in the campsite next to the site. By Friday evening there were around 30,000 people massing around the entrance.

At 3.30am, after the fence had been breached for the third time, the organisers opened the turnstiles. The fans piled through and ran into the darkness towards the stage and settled down for the moment they’d been waiting for, which was still 18 hours away.

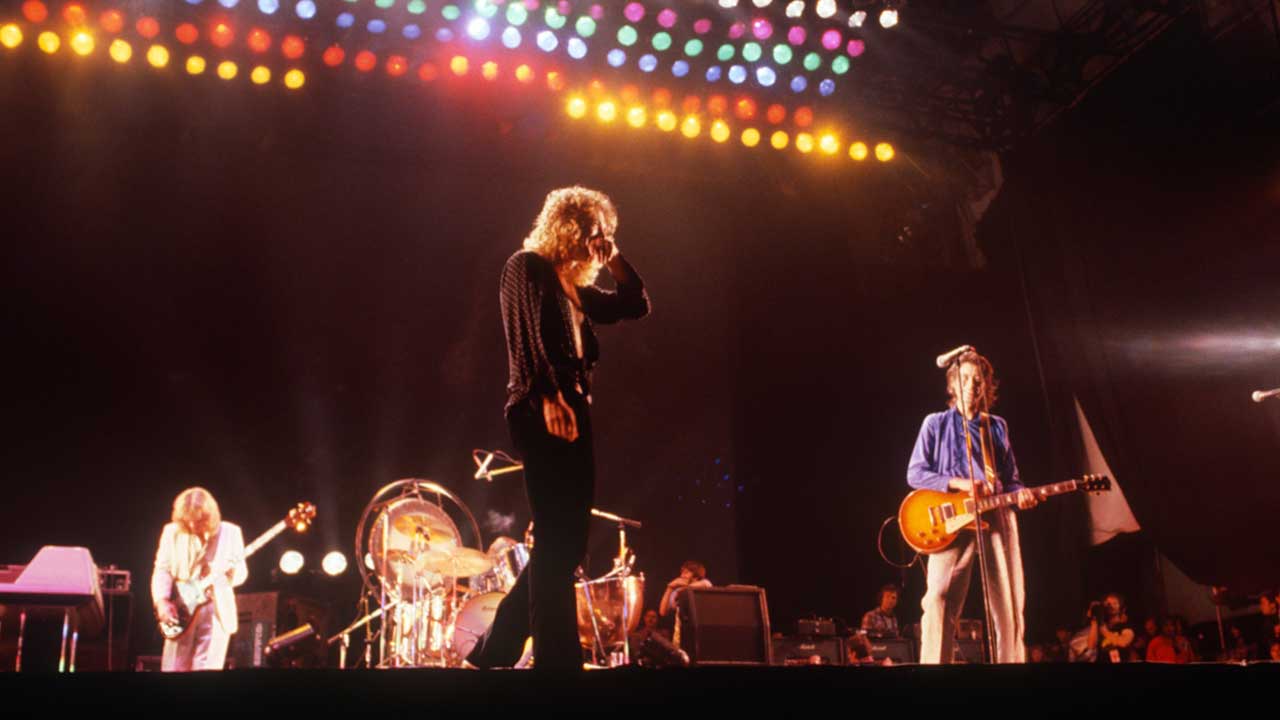

Finally Led Zeppelin walked on with no introduction and launched into The Song Remains The Same. Three hours later they were basking in the adulation of the crowd after the final encore, Heartbreaker.

What and how Led Zeppelin performed at Knebworth was less important than their appearance. For most it was the first (and only) time they saw a band that had not played in Britain for four years.

Knebworth was about the return of Led Zeppelin. The 100,000-watt sound system, the 600,000-watt light show, the white light and swirling smoke that engulfed them during Achilles’ Last Stand, the pyramid laser than encased Jimmy Page during In The Evening – these are the memories that anyone there took away.

But anyone watching the show a second time a week later would have become aware of the sluggish performance, the rambling and often incoherent guitar solos and the reliance on former glories.

There were just two songs from the band’s new album, In Through The Out Door, which still hadn’t been released although it has been recorded before last Christmas. It was as if the last two years – punk, new wave and a new generation of metal bands like AC/DC and Van Halen – had never happened.

In between the two shows there had been a dispute over the attendance figures between the promoter (who said 110,000) and the band (who said 150,000). Backstage the atmosphere, which had been tense for the first show, was downright unpleasant.

Regardless of who you believed, the attendance at the second show was around half that of the first. It was not enough and the promoter, Freddie Bannister, went bankrupt. A couple of months later a full-page ad by Bannister appeared in Melody Maker, clarifying “some misconceptions in the press”.

The ad cleared Zep of any responsibility for the event’s insolvency, stating that the band had “substantially” reduced their guarantee and that manager Peter Grant had been “completely co-operative”. Bannister added that, “It would be a privilege and a pleasure for me to promote another Led Zeppelin concert.”

Sadly, he never got the chance.