What happened when goth went metal: an oral history

A look at the rise of goth metal, which saw some early goths elbowed into the margins or disappearing completely, their thunder stolen by the arrival of goth-leaning bands from the metal world

Goth was born in the 70s and came of age in the 80s, but the 1990s was the decade when it went from being a cult, Anglocentric concern to being a global movement.

Along the way it splintered into dozens of different sub-genres and strands, each with its own tribal characteristics, from the grandiose gothic extremity metal of bands such as Paradise Lost and Cradle Of Filth to Marilyn Manson’s Mephistopholean industrial mash-up.

The 80s goth scene peaked long before the decade that produced it ended. Prime movers such as The Mission and the Sisters Of Mercy were still regular visitors to the UK charts, while The Cure and The Cult had confounded expectations and become huge stars in the US. But its original spirit dissipated as bands began to mutate into something new.

Andrew Eldritch [the Sisters Of Mercy]: When we made [The Sisters’ guitar-heavy 1990 album] Vision Thing, my head was obviously in a Def Leppard mode. Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

Wayne Hussey [The Mission]: I couldn’t just write Wasteland over and over again. There were too many exciting new things going on. And it worked. For a while, anyway.

Nik Fiend [Alien Sex Fiend]: People had moved on to whatever the next thing was. It was like we had leprosy. Nobody wanted to be near us.

Wayne Hussey: By the mid-nineties, The Mission’s momentum had stalled and we were playing smaller venues. It felt like: “What’s the point?”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Jim Morris (Balaam And The Angel): We struggled from ninety-three, ninety-four onwards. We decided to go and do real-world things.

By the early 90s, goth’s old guard were either falling off or fading away. But a handful of disparate keepers of the flame began to emerge from the shadows, bands who came from the metal world but whose sound was underpinned with distinctly gothic sensibilities. Among them were Halifax’s Paradise Lost.

Gregor Mackintosh (guitarist, Paradise Lost): I grew up listening to goth. Paradise Lost was a mixture of death and doom metal at the start, butI had this alternative edge that came from the goth and punk scenes. We were constantly in goth clubs

Dani Filth (singer, Cradle Of Filth): Paradise Lost totally had goth sensibilities. I love the Gothic album [from 1991]. It’s so morose.

Gregor Mackintosh: A journalist said:, ‘You’re not metal, you’re not goth, what are you?’ We just said: ‘We’re gothic metal.’ That was in 1989. We’d never heard the term before. It wasn’t a thing. It didn’t actually become a thing until way later in the nineties.

Three thousand miles away from Britain, an equally unlikely group were plotting an equally unlikely update. New York band Type O Negative were formed by Peter Steele, the former frontman with controversial Brooklyn metal band Carnivore, whose Liberal-baiting songs included Race War. But Type O were an entirely different proposition.

Sal Abruscato (drummer, Type O Negative): Peter [Steele, Type O singer/bassist] loved that goth scene. He loved the girls. We used to go to bars to pick them up.

Gregor Mackintosh: We went on tour with Cathedral in 1990, 1991, and [Cathedral frontman] Lee Dorrian had an early Type O demo. I was a big fan of Carnivore, but this was more hardcore-y, but with keyboards and monks chanting.

Dani Filth: I didn’t pay much attention to Type O until our A&R guy gave us an EP of radio stuff they were doing for [Type O’s third album] Bloody Kisses. And it totally blew me away. It was punky but totally gothic.

Jyrki 69 (singer, The 69 Eyes): I walked past a record store and a guy I knew dragged me in and went:“Listen to this!” It was Type O Negative. It was Bloody Kisses. It sounded like The Cult and Danzig and the Sisters Of Mercy. I went: “This is ridiculous,” and I left. Of course, I soon realised that I was completely wrong.

Sal Abruscato: The whole vampire allure connected with people. It was around the time of that movie Interview With A Vampire [1994], and everything blew up after that. I remember there was a store in St Mark’s Street In New York City that started selling all kinds of ruffled shirts and velvet jackets and shit. And the band started attracting a lot of female fans because of it.

Dani Filth: There was a point where you couldn’t go to a rock club without hearing [Type O singles] Black No. 1 or Christian Women.

Sal Abruscato: We had the gritty, Brooklyn thing. It was unique for the time. The only other thing you could hear with a voice like that was the Sisters Of Mercy.

Ville Valo (HIM): Type O Negative were able to create this really odd combination. They had such dry humour, and at the same time were kind of spooky and kind of fun – you want to get fucked up, get fucked, and at the same time be scared of it.

Sal Abruscato: The goth scene totally embraced us. We ended up playing some weird places. We played this underground BDSM place with all this torture equipment. There were people dressed up and walking round on leashes. We were going: “What the hell are we doing here?” We were just four guys from Brooklyn.’

Cradle Of Filth had bubbled to the surface of the murky pond that was the early-90s UK black metal scene. Their debut album, 1994’s The Principle Of Evil Made Flesh, took the template drawn up by Norwegian bands such as Emperor and Mayhem and added some distinctly gothic flourishes.

Dani Filth: I remember having an album from The Batcave with a load of bands like 45 Grave on there, but I didn’t think the music justified the image. At that point I was into my thrash metal – everything had to be faster and heavier and darker.

Gregor Mackintosh: Cradle went deeper with that gothic philosophy, especially the further they got into their career.

Dani Filth: Our second album, [1996’s] Dusk And Her Embrace, was a total gothic album in sensibility – it’s even got a song called A Gothic Romance on it. Then [1998’s] Cruelty And The Beast is obviously based on the life and crimes of [16th-century Hungarian noblewoman and serial killer] Elizabeth Báthory. I think that cemented our inroads with the goth community.

Jyrki 69: Cradle Of Filth always had that very English gothicness to them.

Dani Filth: Because we’re English, we got tarred with the Hammer Horror brush. It did nark me a little bit. It was quite kitsch. I suppose it could have been worse, though – it could have been the Carry On films.

Cradle Of Filth’s satanic imagery and gleeful blasphemy landed them in hot water on more than one occasion; the front of one notorious T-shirt featured a picture of a masturbating nun under the words ‘Vestal Masturbation’, with the legend ‘Jesus Is A C**t’ written on the back. But they were small fry compared to Marilyn Manson, whose goth-industrial calling card Antichrist Superstar album was catnip to the protestors of America’s religious right.

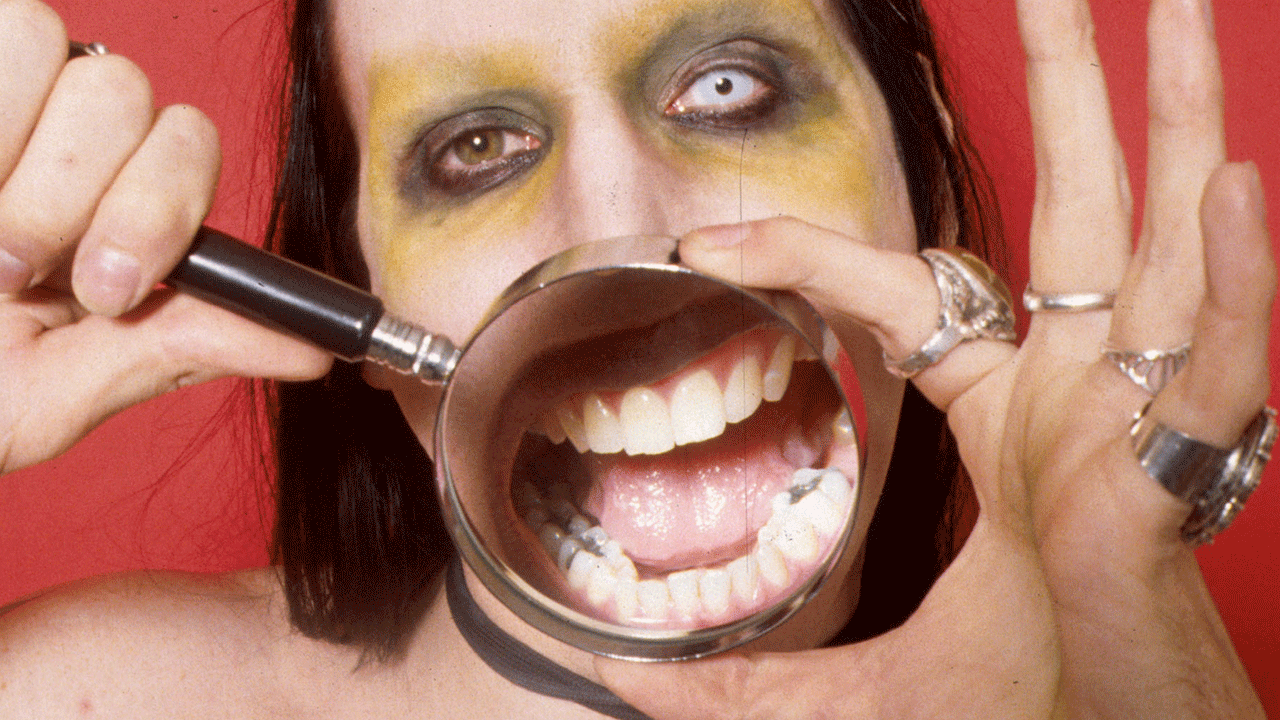

Marilyn Manson: I don’t know what all falls under the technical umbrella of ‘goth’. I think a lot of the bands that originated it, they were taking the piss out of it, because a lot of those bands were British. A song like [Bauhaus’s] Bela Lugosi’s Dead… and then you have bands like Alien Sex Fiend.

Nik Fiend: Yeah, Marilyn Manson looked a bit familiar. Same with Johnny Depp when he did Edward Scissorhands. I thought: “Fucking hell, you’re doing a Nik Fiend there, mate."

Dani Filth: The goth thing with America, they just got it askew. It’s just not quite the same thing. The British invent stuff, the Americans put their own spin on it.

Gregor Mackintosh: You’ve got to give Marilyn Manson his dues, but it was nothing to do with what we were doing. It obviously did have nods to the early-eighties goth scene, but it was more to do with the eighties glam scene, which we were never into at all. It was fun, and we were never that.

Marilyn Manson: I avoided writing vampire songs, until [2007’s] If I Was Your Vampire. That song is the new Bela Lugosi’s Dead. It’s the all-time gothic anthem.

During the late 90s, the boundaries between the goth and metal scenes started to blur. Extreme metal bands such as Portugal’s Moonspell and Sweden’s Tiamat began to channel their inner Eldritch. Paradise Lost, whose 1995 album Draconian Times had seen them being pitched as the British Metallica, suddenly pivoted towards a synth-heavy sound that owed more to Depeche Mode and the Sisters Of Mercy.

Gregor Mackintosh: [Paradise Lost’s 1997 album] One Second was a backlash to the metal press at the time calling us “the new Metallica”. We needed to do something fresh and challenging and new.

Dani Filth: There was a period of time in the late nineties where it looked like goth metal was going to become the next big thing. [Italy’s] Lacuna Coil were very important to that, certainly on their first two records. Moonspell went through a massive goth phase. Bands like Tiamat and Sentenced decided they didn’t want to be metal any more.

Gregor Mackintosh: When gothic metal became more of a thing in the late nineties, it was nothing to do with what we were about. It was just something that had just taken on the look and nothing of the musical sentiment.

Dani Filth: Were we an influence on that? Well, I’m not shying away from it.

Gregor Mackintosh: We toured with the Sisters in the late nineties. We got on with them great. Andrew Eldritch was doing his anti-goth thing at that time. He was going on stage all dressed in white. It was a proper statement of anti-gothness. I found it ironic, cos the songs are so goth.

As the 2000s began, goth found an unexpected new figurehead from the unlikely climes of Finland. Helsinki outfit HIM, fronted by porn shop owner’s son and bona fide pin-up Ville Valo, were Byronic heroes who wrapped their commercial pop-metal in dark romance. Their five-pointed ‘heartagram’ logo positioned them halfway between Aleister Crowley and Mills & Boon.

Jyrki 69: The 69 Eyes had been playing for ten years, and we’d gone from being a hard rock band to more of a goth-rock thing. I loved The Cramps and later [Anglo-American punk/ goth supergroup] Lords Of The New Church, things like that that.

Ville Valo: Finnish music has always kind of been melodramatic. It’s very rarely just about ‘Let’s go into bed and do it all night long’. It’s always been more dramatic and sentimental and maybe more wussy-sounding in that sense.

Jyrki 69: I DJ’d at the very first HIM show, but I didn’t even bother to look at the band. It was just another heavy metal band with a strange name – His Infernal Majesty. After the show, this young guy came over and gave me his EP. It was Ville.

Ville Valo: At the time, when we called ourselves His Infernal Majesty, we had a lot of shit from black metal bands. They were like: “What the hell are you doing? You’re playing this mediocre hard rock and you’re using our imagery!”

Goth still exists, especially when you go to mainland Europe

Gregor Mackintosh, Paradise Lost

Jyrki 69: We started to hang out, and that’s when I realised he had a fresh outlook on a lot of things. I couldn’t find the tracks that led to where HIM were coming from. It was romantic metal for girls, in a way.

Ville Valo. The first time we came over to the UK, we did a goth night at this club, and everybody hated us. We played twenty minutes and then got the fuck out.

Jyrki 69: HIM’s success opened up the door for a lot of bands. We toured with Paradise Lost. They said it was the first time they got girls in the audience.

HIM’s rise coincided with a wider swing in interest towards goth. The mainstream had always dabbled with the genre’s imagery, from 1994 comic book movie The Crow to Madonna’s gothic earth-mother look in the video for her 1998 single Frozen.

Suddenly, bands such as Evanescence and My Chemical Romance were taking the look of goth to a new generation, albeit in diluted forms. Eventually the original goth bands returned too: The Mission, Fields Of The Nephilim and others all re-formed.

Wayne Hussey: We reunited in the early 2000s, then split up again in 2007. I had no intention of coming back to it. But then my manager suggested doing a twenty-fifth-anniversary tour. And we’ve stuck at it since.

Nik Fiend: When we first put a Halloween show on at the Music Machine [in London] in 1984, people didn’t know what the fuck we were on about – fortune telling and cobwebs and smoke machines. Now, you go in Tesco’s and you’ve got two aisles filled up with fucking skeletons.

Gregor Mackintosh: Goth still exists, especially when you go to mainland Europe. There’s a romantic ideal of it.

Nik Fiend: We headlined Zillo festival in Germany: fifteen thousand people, totally up for it. They screamed for the first three songs. I felt like I was in The Beatles, mate. It was very much alive and fucking up for it.

Wayne Hussey: What’s different this time around? Well, there aren’t drugs being immediately laid out on top of the amp when we walk in the rehearsal room.

Nik Fiend: But a lot of them had used what we did, using guitar with drum machines, which was unheard of. Depeche Mode were huge, but it was such a tiddly little sound next to [Alien Sex Fiend’s] Girl At The End Of My Gun or Dead And Buried.

Goth has lasted because it’s a lifestyle – the sensibilities, the atmosphere, the emotion it creates

Dani Filth

Wayne Hussey: I realise our peak time was the eighties and early nineties, but we’ve made some good records recently and we’ve retained a fair proportion of our audience.

Andrew Eldritch: People think that I live in a Bavarian castle surrounded by bats. But no. I’m surrounded by a great many computer screens and I like to watch suspect Japanese films and listen to cricket all day. Test Match Special is so good.

Nik Fiend: The glam thing lasted for a finite amount of time, the punk thing lasted for a finite amount of time, but the goth thing seems to have just gone on and diversified. It’s brought in elements of metal, folk, fetish, everything.

Jyrki: The real goth scene is really electronic. We play at goth festivals and we’ll be one of the only bands there using real back lines. Real goths find us irritating. We’re a loud, obnoxious rock’n’roll band.

Nik Fiend: People still sneer at goth, but I’m not worried. I’d rather people thought it was shit. I thought a lot of things were shit in life, but as I got older I actually got into things when everybody else was washed up with it.

Dani Filth: Goth has lasted because it’s a lifestyle. The spectrum of bands that have been deemed goth are so different to each other that it’s got to be the lifestyle – the sensibilities, the atmosphere, the emotion it creates.

Read more: What we do in the shadows: an oral history of 80s goth

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.