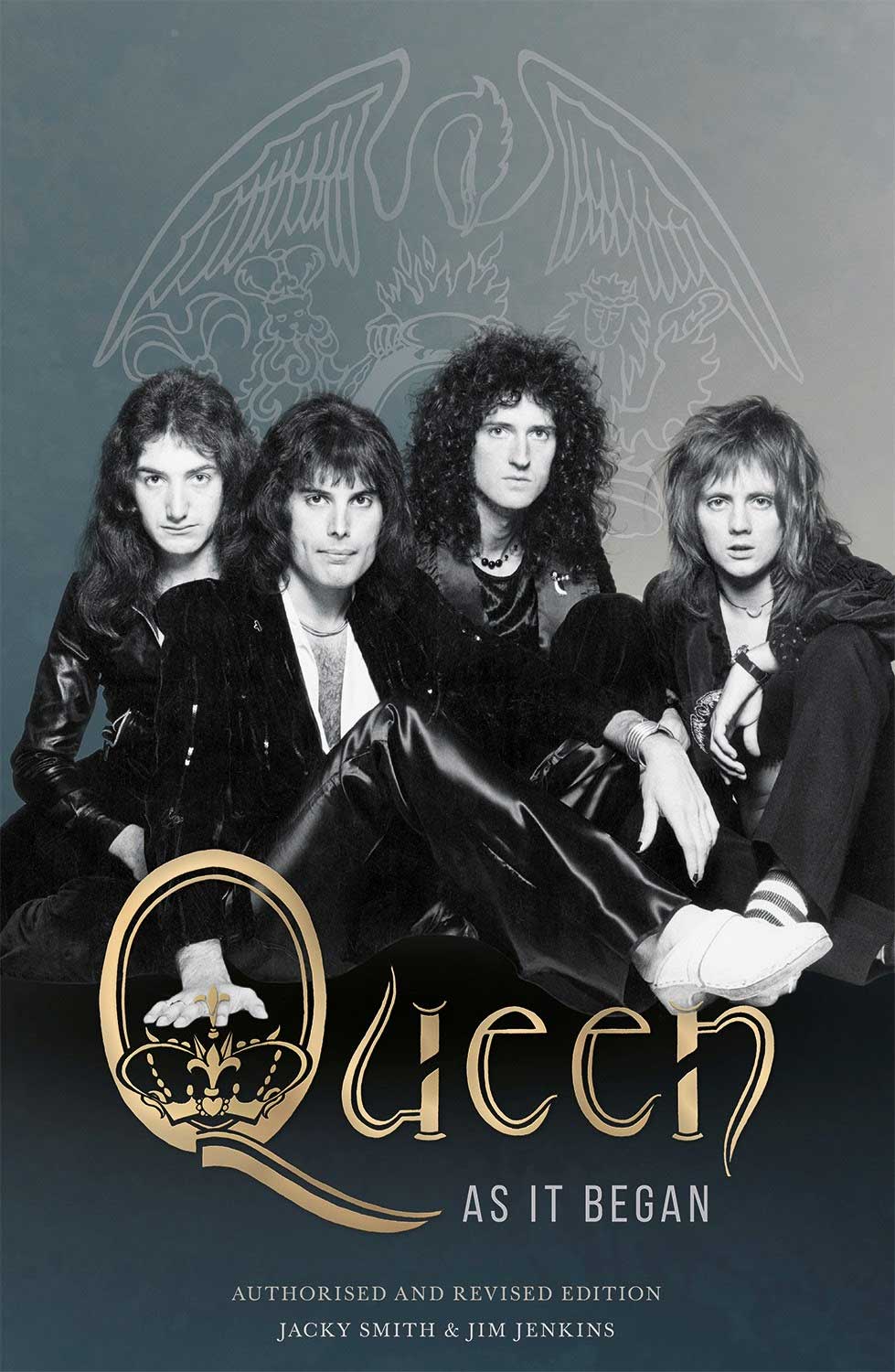

Back in 1992, Official International Queen Fan Club president Jacky Smith and superfan Jim Jenkins published an authorised biography of the band, Queen As It Began. It's since become something of a collectors' item - original hardbacks can sell for hundreds of pounds – but a republished version is on the way.

"We both decided that the time was right for an update on As It Began because we had so much new information and facts from the very early days, thanks in part to speaking to so many people who had come to light over the years and were part of that story." say Jacky and Jim. "We also felt we should document the years from losing Freddie to 1996 - before everyone started to forget.

"The book is a factual document of the time with new insights from Brian and Roger, and additional information from the many people who surrounded them and were a large part of the 'Queen Machine'."

In the edited excerpt below, it's 1981. Queen are visiting South America for the first time, and not everything has gone to plan. Argentinian Promoter Jose Rota has booked the tour on his credit card, while even the band's VIP passes – which featured two women sharing a banana – had fallen foul of local pornography laws.

Queen As It Began - Authorised and Revised Edition, by Jacky Smith and Jim Jenkins, is published on March 24 by Omnibus Press and is available to pre-order now.

On 28 February 1981, it seemed all the problems had been ironed out: everything had gone to plan as Queen took to the stage in front of 54,000 fans at Vélez Sarsfield in Buenos Aires for their first concert in South America, and although bands had played indoor venues on the continent, none had aspired to the huge stadiums that Queen were filling.

The band were nervous and apprehensive. They were under the spotlight from all quarters, as the entire music industry waited to see if their ambitious plans would bear fruit or if they would fall flat on their faces.

Queen needn’t have worried, the fans went crazy, every song they played was recognised and ecstatically received, and the crowd even sang along in English, though few spoke the language. When it came to Love Of My Life Freddie Mercury stopped singing and the audience took over, word perfect all the way through. It was, for Queen, a very moving experience, and Freddie wasn’t the only one to wipe a damp eye.

The following night the show was broadcast live on television to over 35 million people in Argentina and Brazil. After each show, the band were escorted out of the stadium by military police, in some thrilling manoeuvres that would have put movie car-chases to shame. The only reason for such measures was that the local people were concerned for the band’s safety among such joyously riotous crowds – but the band never felt in any danger. The vibes were all good.

The president of the Vélez Sarsfield stadium threw a party for Queen at his home where they were introduced to the footballer – and almost demigod to the Argentinians – Diego Maradona; Brian swapped his Union Jack T-shirt for Maradona’s football-team shirt.

They were also invited to meet General Viola, the president of Argentina, at his house. He had specifically requested a meeting with them as the shows they had given were thought of as a major cultural event in his country. Freddie, Brian May, and John Deacon accepted, but Roger Taylor did not agree with the president’s political views, and so declined the invitation on principle.

There was a short break between the concerts in Argentina and those set for Brazil, which was fortunate for two reasons. The band had wanted to play at the biggest stadium in the world, the famous Maracanã Stadium in Rio, but the promoter had been unable to book it; the governor of Rio had changed the law to specify that the stadium could only be used for football matches and cultural or religious events, and Queen didn’t qualify. The band offered to donate a substantial sum of money to the special charity run by the governor’s wife, but that offer fell on deaf ears, so they finally had to admit defeat.

Negotiations took place to play instead at the second biggest stadium in the world, Morumbi in São Paulo. Eventually, just ten days before the show was advertised to take place, the promoter managed to secure permission for them to perform there. The tickets went on sale immediately and sold out so quickly that a second night was organised, for which tickets sold out in the thirty-six hours prior to the show.

Local security was hired for the band members during their stay in São Paulo, and John’s ‘guard’ introduced himself by saying he had killed 212 people so therefore must be good at his job.

Plans were going well, apart from a small matter. The concert organisers couldn’t have been more helpful – everything the band required they were provided with. However, tour manager Gerry Stickells spotted something odd: "I noticed the equipment they were providing us with had, in every case, always belonged to someone else," he observed. "We were using huge, Super Trouper spotlights, and they all had Earth, Wind and Fire stencilled on the side. Some other piece of equipment had another band’s name on too. It just dawned on me that they had obviously “confiscated” this gear during previous tours."

This caused serious worries about whether Queen’s equipment would be seized at the end of their tour – and the band had with them virtually every piece of equipment they owned. They couldn’t take any chances and after the second Morumbi concert, they decided the gear would be removed with great speed. They chartered a Flying Tiger 747 cargo plane and arranged for it to be on the runway at São Paulo after the show.

Meanwhile, the concerts at Morumbi went ahead. The band walked out on stage on 20 March 1981 to deafening cheers and thunderous applause from 131,000 people, the largest paying audience for one band anywhere in the world to date. Before the show the following evening, while the band were in the dressing room, Gerry was trying to make a phone call. After the seventh telephone he tried failed to work, he grew angry, an unusual occurrence, ripped the telephone from the wall and threw it out of the window.

The police were called and the band locked into the dressing room until the incident had been resolved – but the promoter had failed to realise that they were due onstage at any moment. The band were eventually released to take the stage in front of another 120,000 people.

In total, Queen had played to a staggering 479,000 fans on the tour and had grossed over three and a half million dollars. During that tour every one of the band’s albums were in the Argentinian Top 10 and the single Love Of My Life spent a year in the singles charts – a feat never before accomplished by any band, British or otherwise.

South America had been a triumph for the band and the crew. It had been evident right from that first gig in Buenos Aires, when the band had astounded the Argentinian organisers with not only their stage performance and the response of the audience, but with their organisation from beginning to end. Band and crew flew back to the UK, tired and elated, and knowing that, in a few short months, they would be doing it all again in Venezuela.