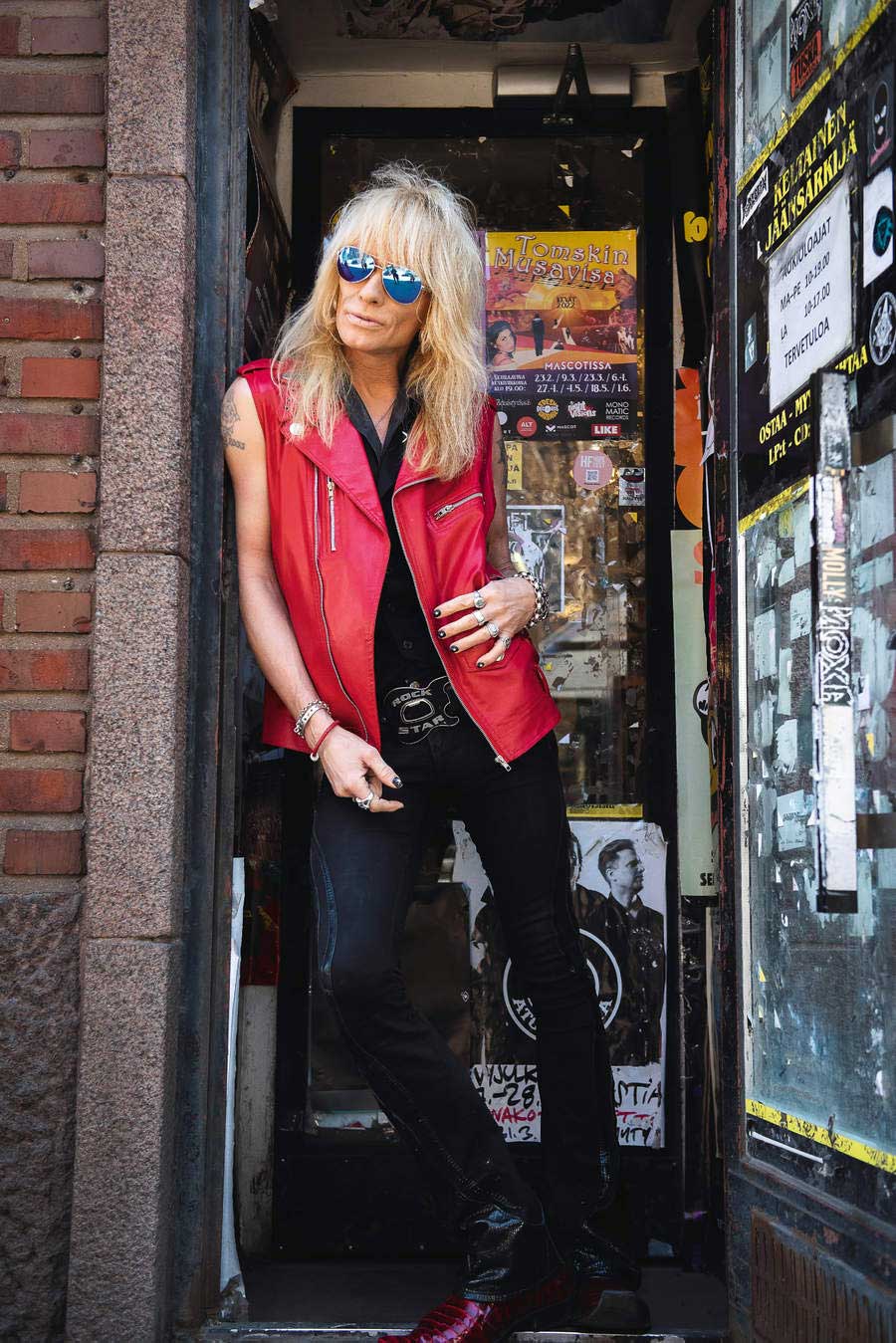

The door of Levykauppa Keltainen Jäänsärkijä record shop opens to a crisp Helsinki spring, yet in blows a hurricane. A twitching, motor-mouthing hurricane in sleeveless red leather, snakeskin boots, mirrored shades and glow-in-the-dark nail stars. Jittering into the shop, it flaps itself with a scarlet fan and checks its sunburst blond locks in a handheld mirror, admirers trailing.

“Are you from Hanoi Rocks? I can’t believe it!” gasps a passing fan who, as he bags an autograph, says he recently left St Petersburg for Estonia… “Because of… y’know.”

“Yeah, it’s not your fault your leader is a dick,” Michael Monroe says with a grin. “Just have a good time in rock’n’roll, okay?”

As ex-Hanoi singer, resurgent Finn-rock hero and judge on The Voice Of Finland, Monroe says he gets that a lot.

“Yeah, yeah,” he jabbers, “but it’s nice, it’s part of the deal. That’s why I always carry these cards with me.”

He hands me a pre-signed cartoon postcard from an inside pocket.

“Autograph cards. If I start signing on a street corner there’d be a line of locals getting autographs. I don’t mind, it’s part of the job. Anyone who complains about being popular is full of shit. Why’d they create a career like that, then?”

Out on the streets here in the Finnish capital – a seamless union of business and bohemia where quaint fishing ships fill the harbour and chic cocktails are worth every cent of their eye-watering price tags – Monroe is a traffic-stopping scandal of brazen rock’n’roll, a walking sliver of Sunset somehow materialised in Europe. But scuttling inside Yellow Submarine (what the record shop’s name translates to) he’s suddenly king of his own glam-rock fiefdom.

The shop – heavy on punk, new wave, rock, prog and metal – was only founded in 1989, and was situated next door between 1993 and 2007, but Hanoi Rocks are embedded in these walls. In pride of place in the racks by the door is a copy of Monroe’s celebrated 2011 album Sensory Overdrive, complete with its cover shot of fabulous fingernails holding open a shocked eyeball: “It’s my eye,” he says, “forced to watch the world in ruins and decay, and I cannot shut them."

Between the Black Sabbath, Misfits and The Who flags decorating the vinyl racks, and beside displays dedicated to The Renegades and New York Dolls, Hanoi posters abound. There’s even a Hanoi Rocks Christmas card from 1983 pinned to a CD rack, featuring the band as such heavily hairsprayed Santas that you wouldn’t want them near your fireplace.

“That was taken in Tavastia club next door,” Monroe says, pointing to a fresh-faced Monroe pouting down from a far wall in late-70s leopard-print. “It was my second ever gig as a singer. I was, like, seventeen.”

What would you say to that guy?

“I’d say: ‘Keep going, you’re on the right track.’”

The poster sets him off on a memory trip to his pre-Hanoi days, homeless on the streets of Stockholm with bandmates Nasty Suicide and Sami Yaffa, learning the art of shoplifting from their fellow vagrants, and chatting up girls in bars solely to gain access to their sofas and fridges.

A pattern for the afternoon is set. We’re here, with 50 euros to spend, to treat Monroe to a strictly budgeted trolley dash around his favourite record store. What we get, though, is a 90-minute tour of a life at the sharp end of rock’n’roll, told through the medium of vinyl.

Even this building itself holds memories: Monroe used to have a management office upstairs, and a fan once calculated that he’s played more than a hundred shows at the adjoining Tavastia club, from the early days of Hanoi to the farewell shows as their reunion ran its course in 2009.

“We did eight shows in six days,” he recalls. “It took some work to maintain my voice all the way to the end. I was actually relieved when it was over. I’ve never left the backstage as quickly as I did after the last song. I just wanted to go home. But you always do a great show at Tavastia, there’s a magical vibe. You can’t do a bad show here.”

Behind almost every record sleeve in the store, meanwhile, lurks a Monroe anecdote, generally drenched in thrill and pathos, and dotted with pithy catchphrases such as “streaming is deceiving”; “music has no business in the music business”; “I started out with nothing and I’ve still got most of it left”.

Touching up his make-up over the Slade section, he recalls going to his first gig, in 1972, aged “eight or nine. I saw them in a teen magazine and I got a chance to go and see the concert, and I was blown away. Noddy Holder was wearing a top hat with mirrors, and they were loud as hell;I couldn’t hear nothing for a couple of days. But it was fantastic.”

Then sight of a Best Of Leonard Cohen compilation reminds him of the time in 1986 when, en route to meet his future wife, he spotted Cohen on the streets of Manhattan. “It was a rainy day, he was in a raincoat and following me with his eyes. I was like: ‘Who is that guy? He looks familiar.’ We went to Judy’s place, and she pulled out this record from her record shelves and said: ‘Have you ever heard of Leonard Cohen?’ ‘I saw the guy on the street today.’ ‘Are you serious?’”

Just as there appears to be little logic to the organisation of the shop’s sections, Monroe’s stories time-jump generations. Seeing a cover of Led Zeppelin II transports him back to his earliest musical awakenings, when his father went into a record shop in 1972 and asked what the kids were listening to these days. His son’s fate was sealed that day.

“He got Led Zeppelin, Creedence Clearwater’s Pendulum, and Love It To Death, Alice Cooper. We got that and it was like: ‘Wow, what is this?’ The sound was so amazing. [Alice] had that husky kind of voice and the image was skinny and starved, the kind of guy with chemistry you wanna go see. On the back cover, Neil Smith had the hair I always wanted, puffing up all straight like mine. Sometimes when it got a little bit longer I puffed it up so it became big, then people thought I started some glam resurgence in LA – all these bands that played hairspray cans better than instruments."

Chancing upon the Nazareth aisle prompts a recollection of bonding over the band with Axl Rose. An altar of sleeves from local 70s-rock heroes Hurriganes takes him to the streets of late70s Helsinki, running for his life from “the James Dean kids”.

“They were a cross between Teddy boys and skinheads,” he says. “They were beating people up, anybody who looked different. People got killed. I had to run a few times. But Andy [McCoy] had the coolest drape jacket, bright red, and leopard lapels, creepers and a fifties hairdo all different colours. I had electric-blue vinyl pants and clothes from a mental institution. We thought it’d be suicide going around with long hair, but if they didn’t know how to categorise us maybe we’d get away with it. The intolerance was incredible.”

He pulls out a portable speaker and fires up Hurriganes’s chunky-rock second album Roadrunner from his phone, air-guitaring along to late guitarist Albert Järvinen’s “phenomenal” solos and drowning out Big Star on the shop stereo. Everywhere Monroe goes, it seems, is a show. Spotting Tom Petty’s Wildflowers in a wall rack, he sings a full rendition of its obscure bonus track – or “fuck-off song” – Girl On LSD word for word. It’s just one example of his detailed knowledge of his territory.

Grabbing MC5’s Kick Out The Jams – an example of what he dubs “junkie touch: you can tell that some players like drugs more than playing, but the attitude was amazing” – he details meticulously the censorship edits. When he falls worshipfully on Cheap Trick’s latest album In Another World, he can list virtually every gig they ever played in Finland.

Across in the vinyl section, he brandishes an Iggy Pop record. “First you got into punk, and then you realised where that was coming from – Iggy And The Stooges, MC5. These guys were really on to something, a real revolution. The government didn’t like it. That’s the closest we’d come to people having the power, because it was in the name of love and peace, so they didn’t know what to do. They couldn’t crush it with violence.”

He’s suddenly reminded of Dead Boys’ Stiv Bators, who nobbled Iggy’s stage gimmick of swinging a mic lead around his neck – with near tragic results.

“Stiv, the only person who ever died on stage for real. He got caught in the lighting rig and was hanging there. The roadies noticed that he was turning blue and there was piss pouring down his leg. He was clinically dead for a while but they took him to hospital and revived him. Someone [also] hit him over the head with a bottle in CBGBs, and he just kept singing until he passed out from loss of blood.”

Furiously flicking through records like a vinyl junkie possessed, and telling a guy filming him without permission to fuck off, Monroe stumbles on a section just made for him: here be Queen, Pink Floyd, Thin Lizzy, T-Rex, the Stones, the James Gang and Deep Purple. Only Hall & Oates soil the section, “or as Stiv used to call them, Hall & Ass. Where’s the Michael Monroe?”

Perhaps he’s twigged that by buying his own records he gets a portion of the cash instead. But soon to be added is Monroe’s new album I Live Too Fast To Die Young. Has he done that?

“Yeah,” he grins. “I’m gonna turn sixty this year, so I can’t die young any more, right? I live my days, I don’t count my years. If you keep a fresh young mind you stay young for ever. I’ve always wanted to maintain that excitement about life and the curiosity as a child, I never want to lose that. It would be boring to wake up one day and go: ‘I’m good enough, I don’t have to try any more.’”

Carved from an original 34 songs, I Live Too Fast is a strident rock’n’roll record with “more air and depth and variety”. Murder The Summer Of Love laments our tendency to tear down exciting movements such as flower power, only to get nostalgic about them later. Young Drunks, Old Alcoholics traces the inevitable downfall of every rock hedonist that ever danced with Mr Jack.

“The industry loves a great train wreck, until it’s not funny any more,” says a man who, surrounded by maniacs, miraculously avoided such pitfalls himself. “All of a sudden you’re on your own, you end up an alcoholic or an addict. It’s gonna catch up with you. It was easy for me. I never enjoyed getting drunk, it made me feel sick and I threw up and felt stupid. My favourite part was the next day when you start getting normal again and the poison leaves your system.

“I had my demons and I went through my heavy period, acid and speed and all that, but I always learned something. I had that one trip, I got to that point where I finally broke on through to the other side. I had an out-of-body experience and I saw what I needed to see there and that was it, that was the last trip I took.”

Donald Duck, you see, had shown him the light.

“I was floating in the water – and I’d been up for two days before on one of these trips that had Donald Duck on the label – and I was up in a bright light and talking to my guardian angel, which was actually my higher self. And I felt great, everything was perfect, now I know about my path in life. It was clear what I wanted to say.

"I was like: ‘Okay, I have a reason to be up there. Not just a pretty face, but I gotta write lyrics that mean something.’ Everything made perfect sense. I thought: ‘If this is death, then fine, great, but if it’s not and I get back in my body, I’ve seen this.’ And everything fell into place. It was an epiphany.”

With that, the hurricane blows back out the door, purchases in hand, off to the nearest café to crank up his portable speaker and sing along to the Stones’ Fingerprint File and – truly bizarrely – Geordie’s Geordie’s Lost His Liggie, a northern folk jig about losing a marble down the toilet, sung by pre-AC/DC Brian Johnson. For one afternoon, at least, Helsinki rocked.

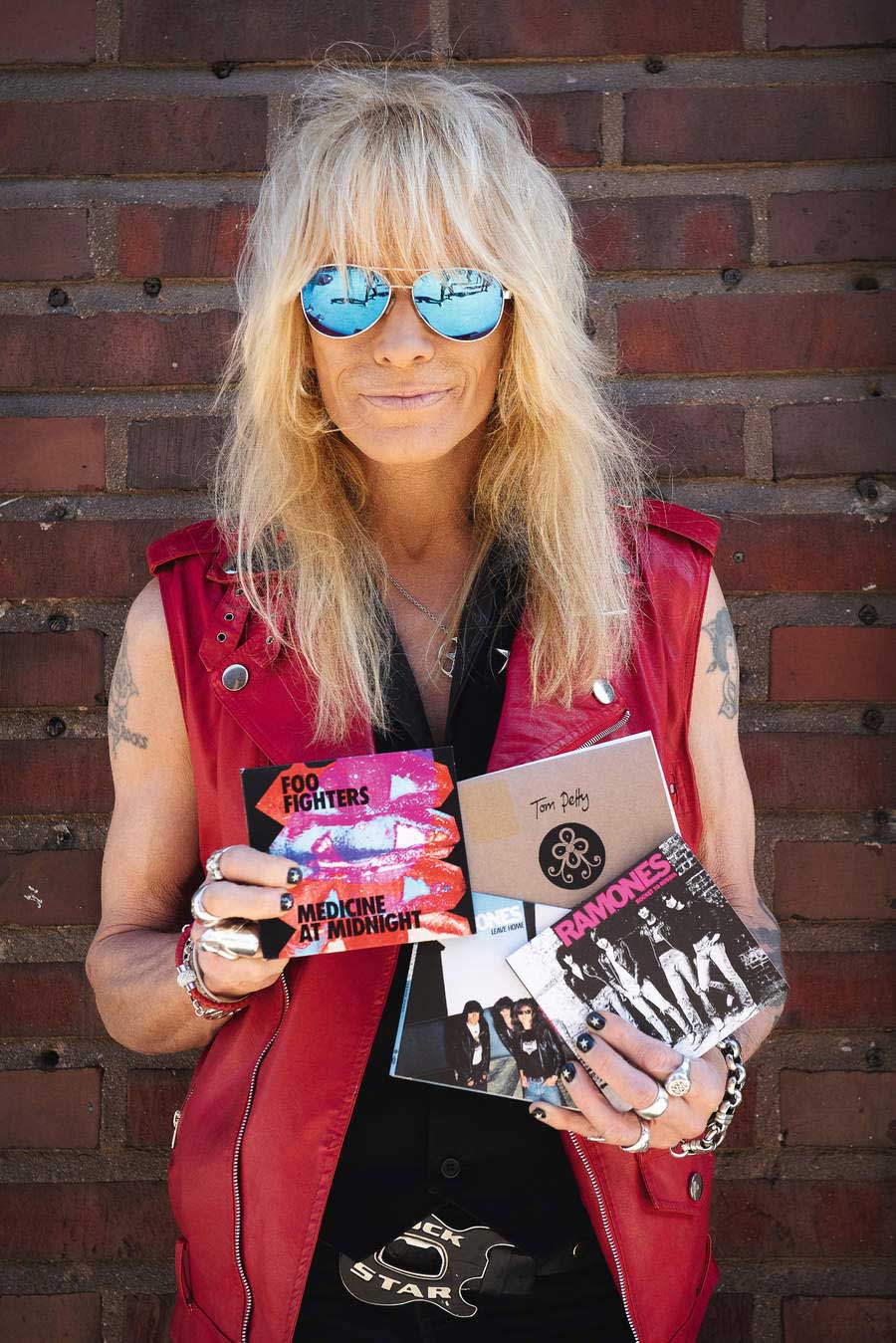

£50 Record Store Challenge - Michael Monroe's choices

Ramones: Leave Home

“They saved rock’n’roll. They came out of the left field and wrote under-two-minute songs: no guitar solos, dumb lyrics, brilliant. They totally revolutionised the situation back then. Big bands were rich rock stars living in their castles and wrote songs that you couldn’t really relate to, and played twenty-minute solos, self-indulgent crap that put people to sleep. Here comes Ramones and suddenly you don’t have to be a virtuoso player, as long as you’re writing songs that are relevant and get a reaction and say something. It was a good kick in the ass for all these complacent rich rock stars out of touch with reality.”

Ramones: Rocket To Russia

“Rocket To Russia was one of the best ones they made. It was the third one, still no guitar solos, every song is great. I love the cartoons.”

Foo Fighters: Medicine At Midnight

“They’re a good example of the continuation of this tradition. This album was incredibly well produced, it sounds so good in every way. When they played Helsinki two or three years ago they invited me on stage four times to jam some harp. The show finished with AC/DC’s Let There Be Rock, with me singing lead.”

Tom Petty: Wildflowers

“The single had a bonus B-side, Girl On LSD, which is here as an out-take. One of the guitar strings is a little out of tune on this version. He’s one of the greatest songwriters, alongside Bruce Springsteen, John Fogerty and Ian Hunter.”