On a cold night in March, Blaze Bayley is in Cardiff for a gig at the Fuel Bar & Music Room.

The place is like a shrine to the singer’s former band, Iron Maiden. At the entrance is a huge mural of Maiden’s monstrous figurehead, Eddie. The house beer is the Maiden-branded Trooper ale. And on one wall is a photo of a famous visitor to the club: behind the bar, pulling a pint of Trooper, Bruce Dickinson, the man whom Bayley replaced in Iron Maiden for five years in the 90s.

Seven thousand miles away, in South America, Iron Maiden are in the early stages of The Book Of Souls tour, on which Dickinson is serving double duty as singer and pilot of the band’s customised Boeing 747 ‘Ed Force One’. In Argentina, the band played to an audience of 50,000 at a football stadium in Buenos Aires. Other shows are in 10,000-capacity arenas – of the kind that Bayley remembers performing in during his time with the band.

In Cardiff, fifty people have paid £10 to see Blaze Bayley. On this current tour, in support of his new album Infinite Entanglement, there are bigger gigs to come, at festivals in Europe and in South America. But in the UK, all the shows are in small clubs.

At Fuel, the entertainment is mostly comprised of tribute acts, jokingly named: Faith No More Or Less, Quitesnake, and the Black Sabbath homage Children Of The Gravy. But there are, in common with Bayley, other well-known names appearing here, including punk star Richie Ramone, and ex-White Lion singer Mike Tramp.

For Bayley, now 52, the realities at this stage of his career are simply stated. “I am,” he says, “an underground niche artist. I’m not in your face, but I’m out there.”

The show he delivers at Fuel, backed by a three-man band, includes material spanning his entire career. There are songs he wrote and recorded with Iron Maiden, songs from his post-Maiden solo albums, and there is one from the band in which he first became famous, Wolfsbane.

There is deadly seriousness in the way he delivers the material from Infinite Entanglement, a sci-fi concept album that forms the first part of a trilogy. But the man has not lost the sense of humour that was so much a feature of Wolfsbane – a band whose fan club was named, with affection, the Howling Mad Shitheads. This much is evident when he introduces the song Kill And Destroy, from his 2002 album The Tenth Dimension, to polite applause. “Come on!” he yells. “I thought if there’s one place where they’d like a bit of killing and destroying on a Wednesday night, it’s fucking Cardiff!”

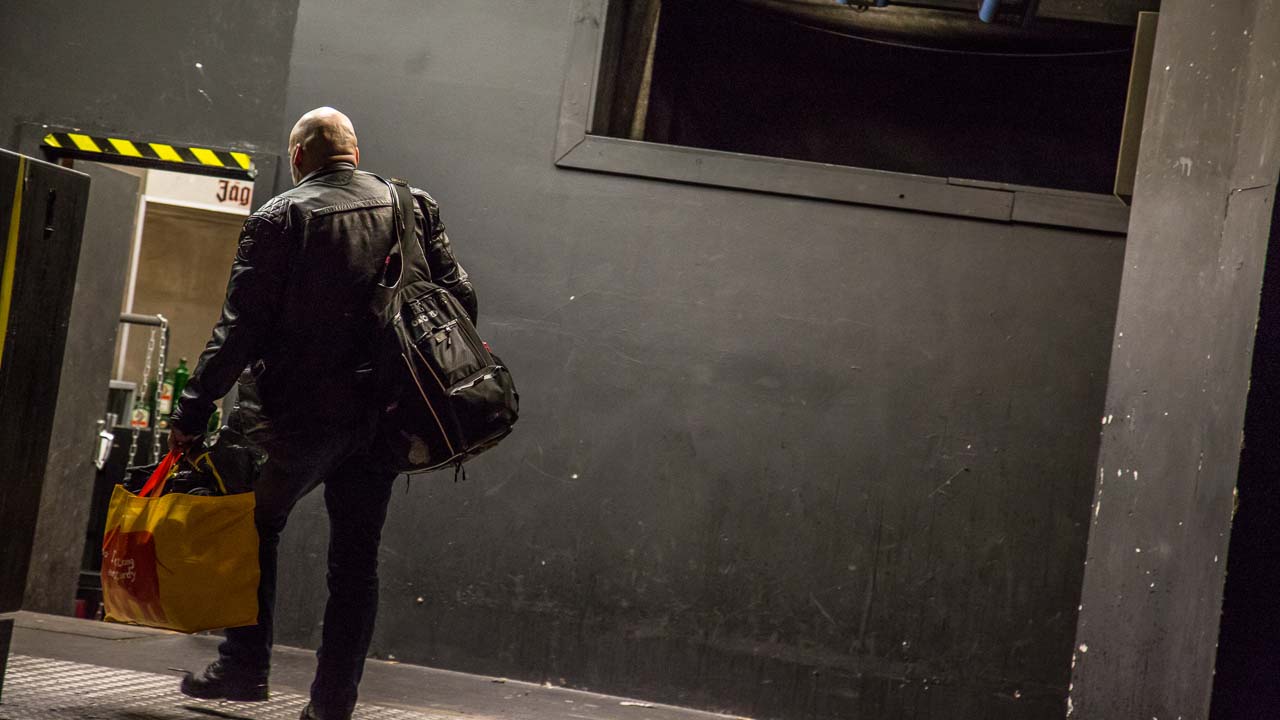

What is also evident, after the show, is the appreciation that Bayley has for the people that come to see him. He spends the best part of an hour chatting to fans – most of whom are wearing Iron Maiden t-shirts. Only when the last CD is signed and the last selfie snapped does he take time out to talk with Classic Rock.

“I owe my living to these people,” he says. “And there’s not a day goes by that I don’t feel incredibly lucky and privileged that I’m a professional singer, singing my own songs.”

We go a long way back, Blaze Bayley and I. It was in 1987 that we first met, at a Wolfsbane gig at the famous old Marquee club in London. What I saw that night was the best unsigned rock band in Britain: four scruffy hooligans who came on like Tamworth’s answer to Van Halen. And in Blaze they had a hugely charismatic frontman, whose witty one-liners could win over any audience, and whose rough-edged good looks led Quireboys singer Spike to call him – after the star of various 70s soft porn flick The Stud – “the Oliver Tobias of rock’n’roll”.

He was also a great interviewee. The first feature I wrote about Wolfsbane for Sounds began with a typically funny quote from him: “I see myself as a wanker in classic tradition.”

For many years I remained close to the band – so much so that when Blaze joined Iron Maiden in 1994, spelling the end for Wolfsbane, I was one of the people that their drummer Steve ‘Danger’ Ellett turned to. He was in tears when he called me, but I had tell him straight: this was Blaze’s big chance; he had to go for it. I also witnessed Blaze’s first gig with Maiden, in Jerusalem in 1995. But as time went on, we lost touch. Meeting him in Cardiff, it’s been twenty years since we last saw each other.

Sitting with him in Fuel’s small dressing room amid the detritus of the touring life – amps, guitars, sweat-soaked t-shirts, the warm beer and curling sandwiches – it’s like old times. But this interview is different to the many we’ve done before.

In these past twenty years, Blaze Bayley has been through the worst of times, both in his professional life and his personal life. After his exit from Iron Maiden in 1999 – when Dickinson returned to the band – Bayley experienced depression. But it was in 2008 that he hit rock bottom, following the death of his wife Debbie Hartland from a brain haemorrhage.

It is with remarkable candour that he will discuss these events. There is also a hard-earned wisdom in what he says about his life in the music business – the good times and the bad.

And yet there is something that has stayed with him – a love of music that it as strong now as it was when I first met him. “I love to sing,” he says. “It’s my curse and my blessing that I’m driven to do it, to the exclusion of so many other things. I have to do this.”

It was in the late 70s that the fifteen year-old Bayley Alexander Cooke decided he would be a rock’n’roll singer. “There was a sixth-form band in my school,” he recalls, “and I looked at the singer and thought, I’d be better than him.”

He had started singing when he was five or six, imitating the crooners that his mother and grandmother loved, such as Mario Lanza and Richard Tauber. When he hit puberty he discovered rock. He got into The Sweet and Slade, and then quickly graduated to punk and heavy metal. “I loved Zeppelin,” he says. “I loved the first Sabbath album – that weird, spooky shit. And then you had the Pistols and The Damned in the charts. It was an incredible time, and it was the energy in punk that gave me the idea that I could do that.” With such sensibilities, it was perhaps inevitable that his membership of the school choir was short lived. “That’s where all the girls were at lunchtime,” he says. “But I got kicked out for being too loud.”

Before Wolfsbane, he had only one band of note, a small-time Tamworth pub act named Child’s Play. He was, he says, “too full of fire for those guys.” But in 1985, he found kindred spirits in guitarist Jase Edwards, bassist Jeff Hately and drummer Jon Buckingham. This was the original line-up of Wolfsbane, formed at a time when hair metal was king. “We decided it would be more interesting to be glam than just metal,” he says. “So we gave ourselves these really outrageous names. Jon was Stakk Smasher. Jeff was Slut Wrecker, then Jeff D’Brini. And I became Blaze Bayley. It stuck.”

By 1987 they had recruited Steve Danger on drums, and recorded a demo tape, Wasted But Dangerous. That demo would change their lives. When Bayley and Jeff Hately went to the Marquee in June 1987 to see the debut UK gig by Guns N’ Roses, they met Slash afterwards, and gave him their tape. Another copy travelled, by a circuitous route, to one of the most powerful players in the American music industry.

Rick Rubin, co-founder of Def Jam Recordings, had produced some of the defining rap and rock records of the mid-80s: LL Cool J’s Radio, Run DMC’s Raising Hell, Public Enemy’s Yo! Bum Rush The Show, the Beastie Boys’ Licensed To Ill, Slayer’s Reign In Blood and The Cult’s Electric. In 1988, Rubin relocated from New York to Los Angeles to launch a new label, Def American, to which he signed Slayer, Danzig and Masters Of Reality. Looking for new bands to bring to the label, he read a Kerrang! review of Wolfsbane’s gig opening for Satanic metal screamer King Diamond at the Hammersmith Odeon. Rubin instructed one of his staff – future Black Crowes producer George Drakoulias – to get Wolfsbane’s demo to him. Drakoulias found the tape at a market in New York and mailed it to LA. And as Rubin later told me: “I played the tape, woke up the next morning and was singing the songs.”

Rubin called the Tamworth number on the cassette box. When Bayley answered the phone it was eleven o’clock at night, and he was in his pyjamas. He thought, when Rubin introduced himself, that it was a hoax. At the end of the call, he still couldn’t quite believe what he’d heard. The hottest music producer in the world was signing this little known band from Tamworth to an eight-album deal.

Sadly, for Wolfsbane, their relationship with Rubin quickly turned sour. According to Bayley, there was an agreement between them that Rubin would produce the band’s first two albums. “The problem was,” Bayley says, “that we didn’t get on so well with the first album.”

While they were recording that album in LA, there was one night that Bayley remembers fondly, when he ran into Slash in a club. “Oi!” he said. “It’s me, Blaze!” Slash responded by singing the guitar riff to one of the songs on that demo, Loco. But most nights, they were too broke to go out. “We were miserable,” Bayley says. “Def American wanted to project this illusion: appear big and successful and you will be. But they were only paying us a hundred dollars a week. So you can’t do fuck all apart from sit around. You can’t take a bird out, you can’t do nothing!”

They came out of it with a strong album. Live Fast, Die Fast was a balls-out, loud-and-proud heavy metal record with a handful of great songs in Manhunt, Shakin’ and I Like It Hot. The album was released in 1989 and greeted with rave reviews in Sounds and Kerrang!, although not in the NME, who claimed that the burger-loving Rubin must have had “ketchup in his ears” when he signed Wolfsbane.

The album was not a hit. This, in itself, was not a major concern for a band on an eight-album deal. What frustrated them was a lack of touring. “We could not get Rubin to understand that we were a band that had to live on a tourbus,” Bayley says. “He would never stump up the money for us to tour.” Worse was to follow when Rubin withdrew as the band’s producer. The job went to Brendan O’Brien, who would go on to produce albums for Pearl Jam, ACDC and Bruce Springsteen, but was a relative novice when he started working with Wolfsbane in 1990.

With O’Brien, the band made the best record of their career, a six-track E.P. that was every bit as OTT as its title: All Hell’s Breaking Loose Down At Little Kathy Wilson’s Place. In addition, Wolfsbane toured the UK as the opening act for Iron Maiden. “I’d met Bruce before when he came to see us play in New York,” Bayley says. “A lovely guy. They all were. It was a great tour with Maiden.” There was also, at Hammersmith Odeon, a bit of fun that turned out to be strangely prescient. As Bayley recalls: “That night, when Maiden played Bring Your Daughter… To The Slaughter, Bruce gave me the mic and left me to sing it while he jumped around…”

What also proved prophetic was the title of Wolfsbane’s second album: Down Fall The Good Guys. Produced by O’Brien, and released in 1991, the album was the last that the band made for Def American. The love that Rick Rubin once had for them was long gone. They were dropped, and from that point, the writing was on the wall.

The band struggled on for another three years. A fourth album, titled simply Wolfsbane, was released in 1994. “We were,” Bayley says, “limping along.” And at the same time, Iron Maiden were looking for a new singer, after Dickinson had quit to go solo.

In a private conversation, Wolfsbane’s manager Gary Garner gave Bayley the unvarnished truth. “I can’t sell Wolfsbane,” Garner said. “I’ve tried. No one’s interested.” He also gave the singer some career advice. “If you have a chance to audition for Iron Maiden, you have to take it.”

Bayley says now: “Up to that point, I hadn’t thought about Maiden. But I realised, this opportunity is going to come once in a lifetime.”

When he auditioned for Maiden, it was in the strictest confidence, by order of the band’s manager Rod Smallwood. “It was horrible having to keep it a secret from the lads in Wolfsbane,” Bayley says. “We’d been so close and been through so much together. It was a confusing time in my life, so bittersweet and melancholy.”

It was Steve Harris, Maiden’s bassist and leader, who told Bayley that he’s got the gig, just before Christmas 1994. The first person Bayley told was his girlfriend, Debbie. The second was his father. To celebrate, Bayley bought a crate of Guinness. Then he had to break the news to the other three guys from Wolfsbane.

“Because it all happened so quick,” he says, “I had to tell them on the phone. It was hard. Very sad.”

- Steve Harris: Genesis Was Never The Same After Peter Gabriel Left

- Wolfsbane: Wolfsbane Save The World

- Iron Maiden: How Somewhere In Time Rejuvenated Metal's Biggest Band

- The 10 Best Iron Maiden Songs Sung By Blaze Bayley

The popular consensus on Blaze Bayley’s career with Iron Maiden is this: that he wasn’t good enough to be in the band; that he couldn’t hit the notes that Bruce Dickinson did: that the two albums he made with Maiden – The X Factor in 1995, Virtual XI in 1998 – are the worst they ever made.

As MetalSucks.com once put it, succinctly and brutally: “Blaze Bayley-era Iron Maiden is awful… an utter crapfest.”

Bayley had to live with this kind of criticism from the moment he joined Iron Maiden, and it’s never gone away, not in all the years since he left the band. “You can’t help but take it personally,” he admits. “You’re human.” His response, from the outset, was to simply ignore the bad press. And he continues to do so. “Early on I said – as dumb as it sounds – I only believe the good reviews. Every bad review, I thought, it’s wrong. I put myself in that place, and that was how I survived.”

What is often overlooked, in assessments of Bayley’s time with the band, is the decline in Maiden’s work in the preceding years. The 1990 album No Prayer For The Dying bordered on self-parody. 1992’s Fear Of The Dark – the last recorded before Dickinson bailed – was not much better. Equally, as Bayley says: “Let’s not forget that Bruce left. His enthusiasm for Iron Maiden had gone, completely. His heart wasn’t in it.”

Bayley understands the circumstances that led to Dickinson’s departure – foremost among them, a disillusionment that first set in after the band’s marathon, 11-month World Slavery tour in the mid-80s, which left him physically and mentally exhausted. “That tour,” Bayley says, “was the real game changer for Bruce. It was the kind of tour that I dreamt of going on, but it really hurt him.”

Above all else, Bayley is simply grateful for what Dickinson’s exit presented to him. “To join this legendary band,” he says, “it was an incredible opportunity for me.” He also admits, with admirable honesty, that he was “bricking it” at the prospect of fronting one of the biggest bands in the world. “I’ll use a football analogy,” he says. “It is exactly the same game in the Sunday league, same rules, but in Maiden it felt like I’d been picked for England. The expectation – the level of intensity – was so high.”

Other singers had auditioned for Maiden. For many outsiders, Michael Kiske of Helloween seemed the best fit. But as Bayley says: “Steve Harris heard something in my voice that he wanted to work with. He wanted to try a different sound.”

When he reflects upon his five years in Iron Maiden, Bayley speaks with great pride. He calls it “an amazing achievement” that Man On The Edge, a song for which he wrote the lyrics and melody, was chosen as the flagship single from The X Factor. He describes that album’s epic opening track, Sign Of The Cross, as “a massive, defining song” – and instrumental in him “finding this other area of my voice”. He is proud, too, of what he achieved on Virtual XI: the emotional depth he brought to Como Estais Amigos and The Clansman, the latter a genuine Iron Maiden classic.

Inevitably, there is sadness when he discusses his departure from the band. He understands the logic behind it. “They had to make a business decision,” he says. “Getting Bruce back, it was the right thing to do. Look at what they’ve done since. I don’t think anything bad of the guys.” At the time, however, he was devastated. He says he never saw it coming – that Steve Harris never spoke to him about the possibility of Dickinson’s return. “When they told me,” Bayley says, “I already had songs ready for the next album.”

It was not all bad. When he was let go, Bayley received a golden handshake. “Maiden took very good care of me,” he says. “I can’t complain about that.” But he spent all of that money on launching his solo career – hiring a band, recording albums under the name Blaze. And in the longer term, he succumbed to depression.

“In Iron Maiden, I was living my dream,” he says. “And when that dream was lost, I didn’t take time out to grieve.”

It was while writing his third solo album Blood & Belief in 2003 – four years after he was ousted from Maiden – that all the feelings he had suppressed finally came to a head. “I found myself in such a dark place,” he says. “All of that pain came out – the disappointment and the rejection I felt – and I went through the most severe depression. Some of the lyrics on Blood & Belief are about my mental health. I felt worthless, really.”

What pulled him through, he says, was the support of his girlfriend Debbie. That, and a sense of his own worth as a musician – ironically, a legacy of his time in Iron Maiden. “I felt I was good enough,” he explains. “I may not have been good enough for Iron Maiden, but my songs and my lyrics were good enough, because they were on Iron Maiden albums. So I had the confidence.”

He kept plugging away: kept the business ticking over, enough to pay the bills. In 2007, he and Debbie married. A year later, his world fell apart. At the age of 38, Debbie Hartland suffered a brain haemorrhage and three strokes. “When she was in intensive care,” he says, “I would not allow myself to think that I wouldn’t get her back. But I lost her.”

Debbie Hartland died on September 27, 2008. Bayley has the dates of her birth and death tattooed on his arm. “She was the great love of my life,” he says. “You only have one love like that.”

He pauses briefly, measuring his words. “When I lost Debbie, things were never the same again. What happened with Iron Maiden, it’s nothing – absolutely nothing – compared to losing the love of your life. That’s when I wondered whether I should give up. But she had so much belief in me, that’s why I kept going.”

For all that he has been through, Blaze Bayley still considers himself lucky – for what he has had in the past, and for what he has now.

His career as a touring musician comes with a price. When he is away, he misses his daughter from his second marriage, which has since ended. “My little girl is four,” he says. “So for me, leaving to go on tour is horrible. But there’s a choice: I could go and get a regular job, or I can do this. And I love what I do.”

Wolfsbane remains a part of his life. Since the band reunited in 2010, they still tour and make albums on an occasional basis. But in the immediate future, his focus is on his solo work – first, his current world tour, and beyond that, the completion of the trilogy begun with Infinite Entanglement. “Right now,” he says, “there are so many things going for me.”

The fame that came to him as a member of Iron Maiden is what continues to sustain his career, all of 17 years since he left the band. As he explains, very simply: “I can advertise as ‘Blaze Bayley, formerly of Iron Maiden’, and it will make just enough people interested.”

He retains a philosophical view on what has become of Iron Maiden, and himself, since they separated. “Maiden are where they should be,” he says, “and I am where I’m happy. The bottom line is, I feel incredibly proud that I was a part of that band. For me, it’s never been a problem that people say, ‘You used to be in Iron Maiden.’ Well, yeah – the greatest band in heavy metal, ever. I’ve got no problem with that.”

Blaze Bayley fulfilled a dream with Iron Maiden. Now, so many years on, it is a different kind of dream that drives him. “I’ve played to ten thousand people a night, and I’ve played to fifty people a night,” he says. “But really, I don’t care anymore, just as long as I’m still making music.

“Music is my life. I put my heart and soul into it. My hero was Ronnie James Dio. He worked until he died. And that’s what I intend to do. All that matters now is that I just keep going. For me, that is the dream.”