The other blues brothers: When Joe Perry Met Johnny Winter

Just months before he died, blues icon Johnny Winter and Aerosmith’s Joe Perry met for the first time to talk hell-raising, music-making and the price of fame.

He may have just entered his eighth decade, but Johnny Winter is having a moment. One of rock’s great survivors, the grizzled Texan blues-rock pioneer is as busy now, at the age of 70, as he’s ever been.

As well as a career-spanning new box set – the aptly titled True To The Blues: The Johnny Winter Story – there’s a warts’n’all documentary on the horizon: Down & Dirty, which covers both his lengthy music career and the battles with booze and drugs that have accompanied it.

No less intriguing is Step Back, the second in a series of covers albums – Winter calls them ‘tributes’ – that find the singer and guitarist recording songs by some of his influences from the 50s and 60s, accompanied by friends and contemporaries, such as Eric Clapton, ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons and, on a version of Lightnin’ Hopkins’s Mojo Hand, Joe Perry.

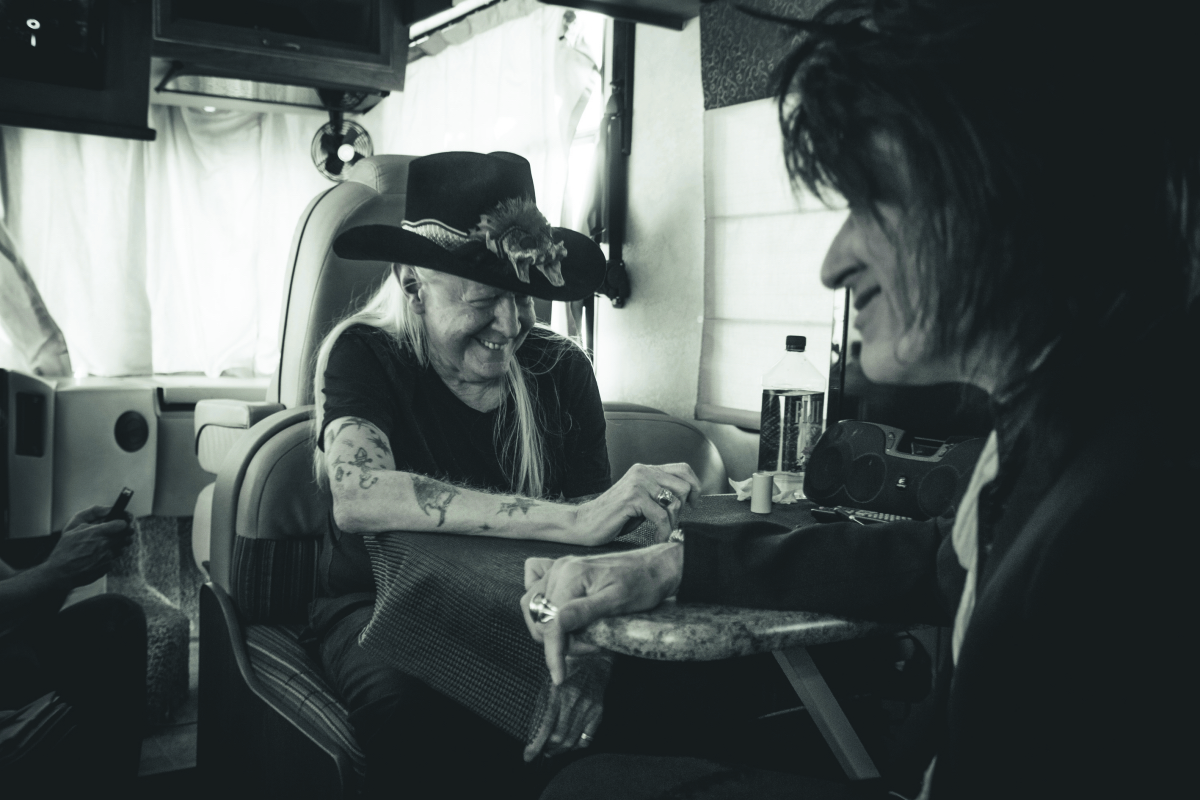

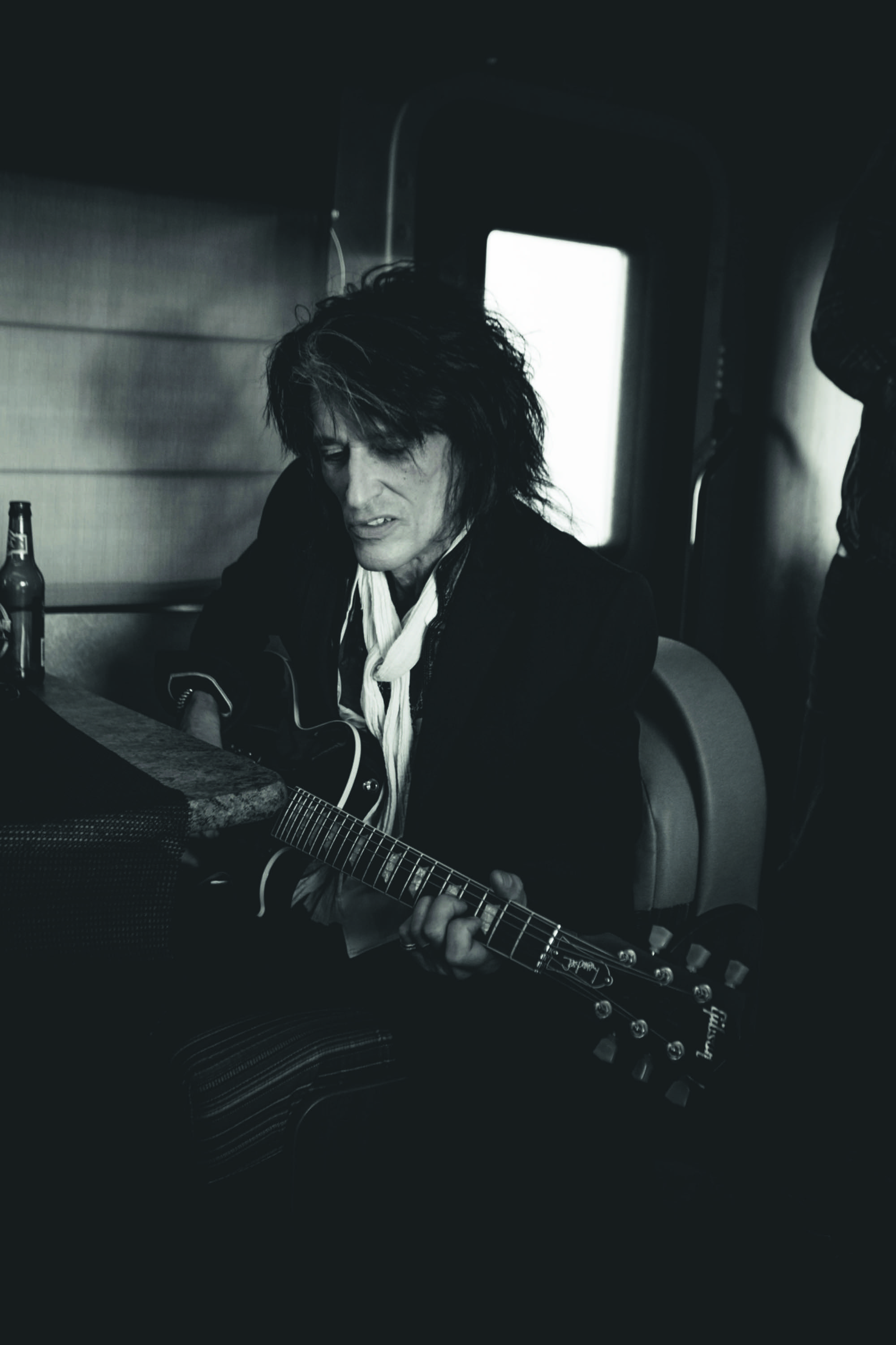

Not entirely coincidentally, Perry is currently perched on the edge of a sofa in Winter’s trailer parked outside LA’s Saban Theatre, a couple of hours before the latter is due to take the stage. Classic Rock has engineered a meeting between these two icons, who, despite similarly lengthy careers and a shared love of the blues, have never met before.

Indeed, the Aerosmith guitarist is especially enthused to meet the more laconic Winter. Back in the late 60s, Perry was one of those hungry Young Turks who soaked up such groundbreaking Winter albums as The Progressive Blues Experiment and Second Winter, taking cues from Winter’s soulful playing that he would later incorporate into Aerosmith’s arena-wrecking mega-hits. “I’ve been influenced by Johnny probably since I was about seventeen or eighteen,” says an uncharacteristically effusive Perry. “I’ve always loved his music.”

And is this really the first time your paths have crossed?

Joe Perry: This one time, many years ago, at the Academy of Music in New York in 1972 – this was before we had a manager – [Winter’s former manager] Steve Paul had heard of us and said: “I’ve got this show with Humble Pie and Edgar and Johnny Winter, and I’ll give you twenty minutes so I can check you out.” So we played that show, did our twenty minutes, and he passed on us. Johnny and I might have passed each other in the hall that day, but that was probably it. But I remember going to see him at a club called the Boston Tea Party in Boston in 1969. That was Johnny and Rick Derringer, and it was a really kick-ass rock band. That show got me to put a slide on my finger. And I haven’t put it down since.

I think you’re both bluesmen, at the core.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

JP: I am as much as I can be, really. Johnny’s got the credentials and he’s played with a lot of the greats. I was more the next generation. Just like Johnny, I’m just another link in the chain. The thing with the blues is, you can play the same song every night, and every time it’s a different song. At least for me it is. We carried that over into rock’n’roll. I mean, we’ve done some songs that were pop hits, they weren’t the blues, but I tried to carry over that feeling, to make them a new song every night. It’s not the blues per se, but you’re giving it that platform, you’re giving it some guts. That’s what I got from Johnny, watching him pour his heart and soul into it.

Johnny, when did you first realise that you were going to be a blues player?

Johnny Winter: When I was twelve, hearing the blues on the radio. I thought: “I have to learn how to play this, this is cool.” It was just more emotional, it had more feeling, than any other kind of music I ever heard. It just makes you feel good. I still love hearing it, and I still love playing it.

Which is better – being successful, or being hungry?

JW: I like being successful a lot better [laughs].

JP: I like to have a comfortable bed, and I like to eat once in a while. But I have to say, some of my best times were back when we were struggling.

JW: That was very fun, when you’re still trying to make it.

JP: It’s that time when people you don’t know start showing up at your shows. At first you’re just calling up all your friends to come to the club so the owner thinks you’ve got something going on. But then there’s that night when there’s new faces in the audience, and you realise you’ve got something that they want to hear. That’s a great feeling.

Johnny, when you were coming up, were you on a different circuit to bands like Aerosmith?

JW: Not at first. I was playing rock and R&B for a long time before I started playing the blues. Until the British bands came around, white people didn’t even want to hear the blues. It wasn’t until the Rolling Stones and John Mayall and people like that, when white people started caring about the blues. So I didn’t really get to start playing it until about 1967. I never wanted to be a rock star, it’s just that Steve Paul wouldn’t let me play the blues.

How did audiences react when you first started playing the blues?

JW: There were only a couple of places to even play it. There was a club called the Love Street Light Circus in Houston, and a place called the Vulcan Gas Company in Austin. I wasn’t making nearly as much money playing the blues. It was really my drummer ‘Uncle’ John Turner’s idea. I didn’t know if we could make any money off of it. And for about a year we didn’t. They paid us fifty dollars a week. We were really struggling, sleeping on floors and stuff. And then a Rolling Stone article came out about us and everything changed overnight. Suddenly we were playing big festivals. The week before, we were playing to a hundred people.

Was there one show where you realised you were a success’?

JW: I’d say Woodstock. That’s when I thought we’d pretty much made it. There were so many people there. There was mud everywhere and nobody knew who was going on when. It was a big fuckin’ mess. We had to take a helicopter out of there, you couldn’t drive at all. I remember flying over the crowd, just thinking: “Look at all these fuckin’ people.” It was really something else.

JP: You look at the careers of the bands that played Woodstock, and that was the show that put most of them on a national level. I mean, Ten Years After were kind of a one-trick pony, they didn’t have much backing them up, but the bands that had the stuff, Woodstock made ’em.

Did you go to Woodstock, Joe?

JP: I’m not really a mud person. I heard about it, I knew it was going on, but I stayed in New Hampshire that weekend. But we were asked to play the anniversary show. Steven [Tyler, Aerosmith singer] and Joey [Kramer, drummer] were both there, and they were talking about tripping and getting muddy, and I was like, just get me in and out without any mud. It was really crazy. There was a little of the vibe of the first one, I think – a lot of people showed up with knapsacks and tents – but there was also a lot of Coca-Cola signs all over the place. That put a crimp in the vibe, for sure.

Corporate sponsorship wrecked rock’n’roll.

JP: The way the business has gone, I think you’re seeing the end of a really cool era. I think we were fortunate to be able to see it, to see bands of real quality playing in clubs and theatres in the sixties and seventies, and you got to see that all grow and grow. It didn’t used to be about money, at least not for the musicians. In the beginning, nobody made money making records. You put out a record to advertise your tour, and you toured to sell records. The guys that made the money were the lawyers and the managers. We got to go out and play and party and get laid, and that was it.

Johnny, is the lifestyle of a bluesman the same as the lifestyle of a rock’n’roll star?

JW: Pretty much. Rock stars make more money, they take more drugs. Blues guys mostly drink, smoke a little pot. They don’t do a lot of coke or heroin.

Would you rather hang out with blues guys?

JW: Oh yeah. They’re a lot friendlier, a lot more willing to help you out.

JP: Blues players are a little closer to the road, a little closer to their audience, a little less concerned about the charts and all that stuff. Those are the kinds of guys I’d like to hang out with.

When was the ‘golden age’ for seeing live music?

JW: The 1950s, for sure. It was a great decade for music. There was a lot of great blues, and rock’n’roll had just come out. It was some of the best music I’ve ever heard and some of the best shows I’ve ever seen – stuff like early Elvis, Fats Domino, Little Richard. I loved it.

JP: For me, I think it was the education I got when the English guys came over and turned Americans on to American music. I have to say it was the Stones. They really stuck to their guns. They were really surprised when they came over here and turned on the radio. They expected to hear the blues. They couldn’t believe we weren’t listening to the blues in our own country. When they would come on a TV show here, they wouldn’t come on unless they also had, like, Howlin’ Wolf on. I remember seeing that on Shindig.

JW: He would’ve never gotten on without those guys. They did a lot for the blues.

JP: And they gave credit to people. I mean, I love Jimmy Page and everything, but he put his name under a lot of things that he shouldn’t have, let’s put it that way. But the Stones always gave credit where it was due. After they got bored with being pop stars, they really got into their roots. Exile On Main St is a hardcore blues record. And it turned a whole generation of white kids on to the blues. Johnny covered a lot of Stones over the years – Silver Train is one of my favourites.

Did you know the Stones, Johnny?

JW: Yeah, I knew Mick and Keith. I once went to a party they were having, and I got so drunk that I went into the bathroom and passed out. My wife had to drag me out. That was a good party.

Given all the rehabilitation involved, is the rock’n’roll lifestyle really worth it?

JP: After a while, you realise how much it’s taken out of you.

JW: I would’ve died if I didn’t stop. I’m sure of that. The kind of stuff I was doing, there’s no way I’d still be here if I didn’t quit.

JP: Your body’s only got so many drinks in it. It’s only got so many hits of blow, so many pills it can take. When you’re born, there’s a set amount that you’re going to be able to take before it turns around and bites you on the ass. Some people can do it forever and they’ve learned to control it. Other people, within a year they’re dead. And you don’t know that when you’re drinking your first drink or taking your first hit. It’s playing with fire. At first you’re just having a few drinks, maybe nursing a hangover the next day, but eventually it affects your playing, and you end up not caring as much, and if you let it get that far, your body starts falling apart.

Of course the mythology is that drugs and alcohol fuel the music, that you wouldn’t have been able to make it without them.

JP: Well, it helps you bear the road. But one of the things that got me sober was I realised it was the music that got me high in the first place. The first time I heard the music that inspired me, I was stone-cold sober. So I think back to those times and I realise it was already in there.

Does the blues work as well stone‑cold sober?

JW: I know it does. I like it a lot better, actually. I know I play better.

JP: For sure. You want to hear what your rhythm section’s doing, you want to react to that. If you’re out there sober, you can do things you never thought you could do.

Johnny, what’s your favourite show that you’ve ever played?

JW: That’s a tough question. There’s been a lot of great ones. Probably Woodstock, though.

JP: There’s different reasons why a gig can be good. But one that got me down deep in my soul was a show we did last year. When Aerosmith first got together there were five of us living in an apartment together. I rented the apartment. We were five guys, all struggling to make it. Forty years later they wanted to put a sign on the building as a historic site. So we did a gig on a flatbed truck, right out in front of the building, and forty-thousand people showed up. Just standing there and looking at all those people, and turning around and seeing where my old bedroom was, forty-two years ago, that one really hit me. I don’t know if we played great. All I know is that forty-thousand people showed up and it was really an amazing thing.

Johnny, you have a documentary coming out, Down & Dirty. What was it like making it?

JW: It was a lot of fun. They followed us all over, from Japan to Europe, everywhere. It covers my whole life story, good and bad. Joe’s in it.

JP: I am?

JW: Yeah. And you look good [laughs]. I saw it a few months ago, at the premiere at South By Southwest. I really loved it.

Does it have everything you’ve always wanted to know about Johnny Winter?

JW: Yeah. Probably more than you’d want to know.

How do you guys feel about the state of rock’n’roll these days?

JP: Everything is so compartmentalised these days. So specialised and industrialised. I couldn’t tell you Justin Bieber from Lady Godiva or Lady Goo-Goo or whatever her name is. I mean, more power to them, they’re the latest thing, but I just don’t hear that stuff.

One thing’s for sure: when you guys stop playing, it’s all over – the whole notion of ‘classic rock’.

JP: That’s what I was saying earlier – it’s the end of an era. The Stones are still out there doing it. I’d like to be the last one standing, but with those guys, who knows? Seeing this whole thing go from basically a cottage industry in the fifties and sixties, through the punk thing, then the MTV era. That was a crazy time. The record companies were pouring out money like it was water. Then Napster came and killed the record industry. That was fine for us, because we make our living playing live, but it knocked off a lot of people who made a living selling records but didn’t do well playing live. Guys like Johnny and I were fortunate enough to come up in a time when you had to be good at playing live to make it. But the era that we’ve all known and loved is over. When a guy like Billy Joel says he’s not going to write any new songs because it’s a waste of time, that all anybody wants to hear are his hits from way back when, that’s when you know it’s really over.

Johnny, are you ever going to quit?

JW: I don’t think so. Not unless I’m no longer physically able. Otherwise I’m gonna keep going.

Joe, do you have a favourite Johnny Winter song?

JP: TV Mama. I love the lyrics, I love the feel of that song. But of course there’s so many that I like, and I might really love the solo on a particular song, so it’s hard to pin down just one. But I think that album [Nothin’ But The Blues, 1977] is the best of them. Johnny’s records are part of that lexicon of music that I have to keep with me at all times for when I need that kick in the ass.

Johnny, do you have a favourite Aerosmith song?

JW: Probably Walk This Way.

JP: [Laughs] I’m surprised that he even knew who we were, to be honest. I mean, give me a break. We’re from different worlds.

Johnny Winter’s True To The Blues: The Johnny Winter Story, is out now on Columbia/Legacy. For even more pics go here.

Classic Rock contributor since 2003. Twenty Five years in music industry (40 if you count teenage xerox fanzines). Bylines for Metal Hammer, Decibel. AOR, Hitlist, Carbon 14, The Noise, Boston Phoenix, and spurious publications of increasing obscurity. Award-winning television producer, radio host, and podcaster. Voted “Best Rock Critic” in Boston twice. Last time was 2002, but still. Has been in over four music videos. True story.