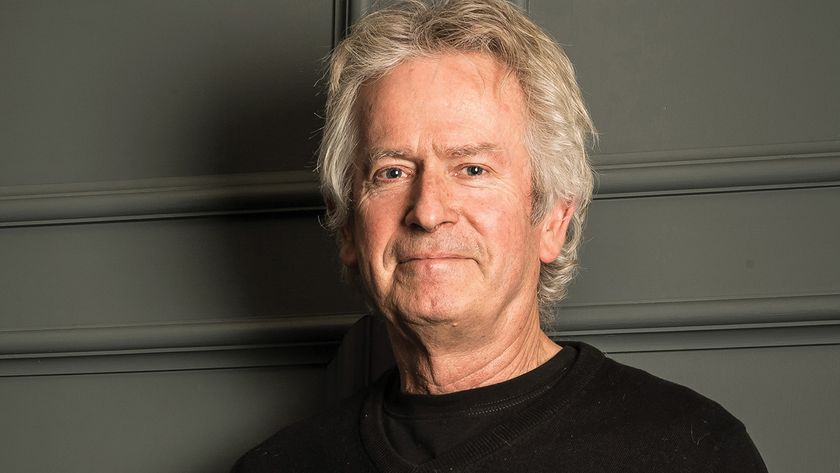

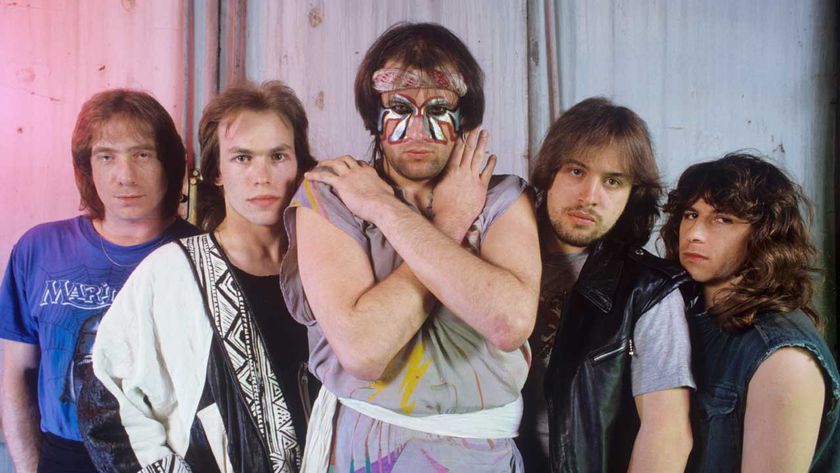

Mick Wall’s book Like a Bat Out of Hell: The Larger than Life Story of Meat Loaf relates the story of Meat Loaf, an overweight Texan teen who went on to become one of the biggest stars on the planet.

Not long after releasing Bat Out Of Hell in 1977, the world lay at Meat’s feet. The album was selling by the bucketload, producer Jim Steinman was ready to record a follow-up, and Meat’s star was firmly in the ascendant. But then something terrible happened… he lost his voice.

This extract from Wall’s book tells the tale.

It began with a noise, an unholy noise, a noise that no one had heard before. It came out whenever he tried to sing. It began with the high notes, the ones he used to hit with the accuracy of an army sniper.

‘HHGGGGGUUUUURRRRGGGGHHHH!’

The sound of air being forced from a kettle, of strangulation. The sound of a bat trying to find its way out of a deep, dark cave. ‘I asked Meat Loaf to come up and start just rehearsing, just so I could hear what shape his voice was in,’ Steinman recalled in a BBC Radio interview. ‘And he opened his mouth and we both like just looked at each other in shock – because the sound that came out of his mouth didn’t even resemble a human voice … It was like this low, guttural sound – like a dragon trying to sing. It was a horrifying sound, and there was no way we’d be able to do a record like that and he didn’t know what to do. He just stared at me, sort of helplessly, and said, “What do I do now?” I said, “I think you better go get help.”’

‘HHGGGGGUUUUURRRRGGGGHHHH!’

Jim and Todd just fucking stared at him.

‘I can tell you very specifically,’ Steinman told me, ‘his voice was great for about month but he didn’t do anything to train it, or keep it going right, it just got abused or something happened psychologically, which was part of my [original] point to David Sonenberg. About a month into the tour his voice basically had gone, and he didn’t take time to rest it. And it just was a very kind of horrifying, fascinating situation for me to see crowds of up to twenty thousand screaming along with this record and performer of my music. And I’m on stage at that point … where he didn’t sing one good note the whole night. The perverse thing for Meat Loaf was not being even a bit self-aware of the situation.’ He got away with it, ‘because sometimes people bring enough of the record with them that the last thing they’re paying attention to is the performance. There are performances that are very well known, such as the Old Grey Whistle Test thing, where he didn’t sound great. It’s like only if you listen to the record can you [detect] an appreciable depreciation, so to speak.’

A year on, Meat’s voice sounded inhuman, animalistic. He knew that he could sing. It was still there at the lower end. At least it was at first. The damage wasn’t physical, it was psychological. As he later wrote in his autobiography, ‘The doctors all said, “Meat is fine physically. It’s all mental.” But psychosomatic or not I still couldn’t sing.’ From somewhere deep down inside, his body was in rebellion, refusing to do the thing he loved to do.

It was weird.

‘HHGGGGGUUUUURRRRGGGGHHHH!’

It was fucked.

He thought about Jim working on the album with Roy Bittan and not him. He thought about Todd dismissing his ideas. He thought about the songs he couldn’t fully embrace and hadn’t had the chance to shape. He thought about the great effort it took him to get into character to sing them. He wondered if his subconscious was stopping him, trying to save him from the madness that he’d lived through during the end of the Bat tour, the hideous physical and moral decline he’d fallen into.

‘HHGGGGGUUUUURRRRGGGGHHHH!’

They sent him to doctors, one after the other, progressively more senior and eminent, New York thousand-dollars-an-hour specialists, and they all told him the same thing: ‘There’s nothing wrong with you.’ And then the whispers began. He wasn’t sure if they were real or not at fi rst, but it soon became clear they were. He’d lost his voice and now he was losing Jim. Jim was the guy who wrote the songs. Jim was the dark and brilliant presence behind Bat. He was just the singer and if he couldn’t sing, then what use was he, to Jim or to Cleveland International, who were getting increasingly freaked out and impatient? Everyone around him was wired up, crazed by excess, fuelled by booze and cocaine. Everyone wanted something, and for a while what they wanted had been him.

Now it wasn’t, not any more.

‘HHGGGGGUUUUURRRRGGGGHHHH!’

He stopped going to doctors and started going to faith healers and oddballs – guys that hit him with kitchen implements while he hung upside down like a fucking bat. Steinman later told an incredulous Sandy Robertson about ‘the witchdoctor’ in California that Springsteen’s manager had recommended. Claiming the guy had fixed things for Jackson Browne and Bonnie Raitt. A guy named Warren Berrigan who told Meat that he’d been traumatised when he fell off stage and injured his leg all those months back in Ottawa. Said Steinman: ‘The guy’s treatment is he injects you with your own urine and then he beats the shit out of you! He has Black & Decker power tools, huge saws, axes … He puts rubber pads on your body and he pounds for three hours and you scream.’ He added, nonchalantly, ‘I can’t imagine Jackson Browne going through this.’

Mick Wall’s Like A Bat Out Of Hell: The Larger Than Life Story Of Meat Loaf, is out now.