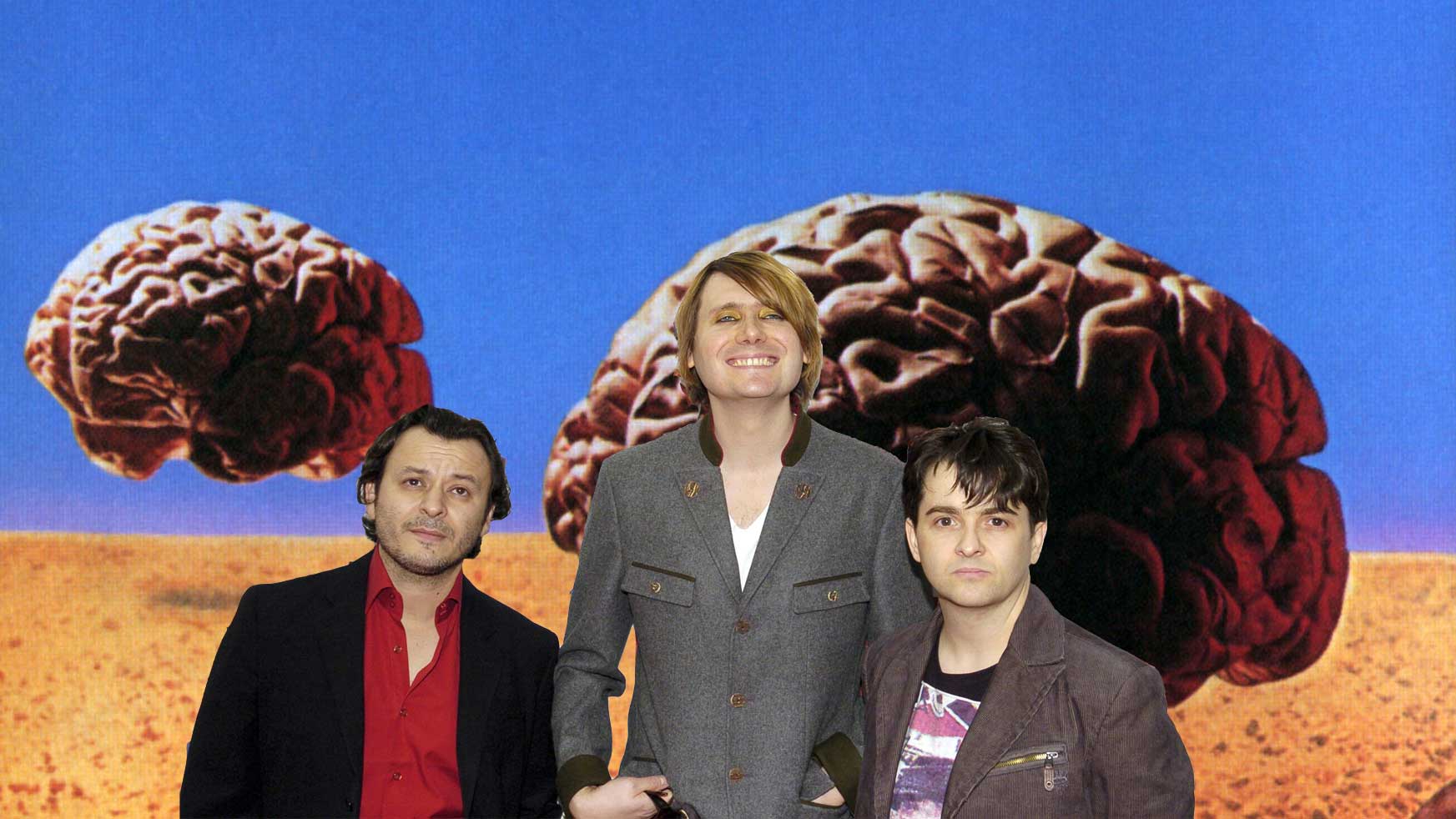

By his own admission, Nicky Wire is more nervous than when he met Fidel Castro. Rush are on stage sound-checking for the first of two shows at Wembley Arena. The Manic Street Preachers – James Dean Bradfield, Nicky Wire and Sean Moore – are walking into the auditorium when the long black drapes at the rear of hall part momentarily to reveal Geddy Lee hunched over his keyboard.

As someone once said, music makes teenagers of us all. And as Nicky and James sit down to interview Rush for Classic Rock, both Manics look very fresh-faced indeed. James has his questions scrawled on the back of a newspaper; Wire has pages of A4 neatly anointed with questions and notes. James says that Wire has four obsessions in life: sport, certain painters, stationery and Rush. Given the Manics’ famously dogmatic stance you might imagine that they have more in common with The Clash than Canada’s favourite sons.

Strange to relate, but Rush have a following in Wales that borders on the hysterical and not even the Manics (who hail from Wales, natch) are immune to it. This journo has known Nicky for a number of years and the last time we spoke we argued for ages about whether Moving Pictures or A Farewell To Kings was the greater album. Here’s what happened when the Manics grilled their heroes.

Nicky Wire: Far Cry [the first track on the Snakes & Arrows album] sounds like such a classic Rush record – especially those musical stabs. It just transported me back in time. When you went in to record it, was it your intention to make a classic-sounding Rush album?

Geddy Lee: I don’t think we really know how to make a ‘classic’ Rush album. I don’t think it’s something we’re capable of doing. Just like when you guys get together, you try to do something you like, that tickles your fancy in some way…

James Dean Bradfield: But with Far Cry, you must have heard echoes of what people call classic Rush?

GL: We intentionally threw in that chord at the end of it from Hemispheres; that was one of those obvious nods to ourselves because we knew it was something a lot of our fans would be into. It was like an inside joke for them.

Alex Lifeson: Nick Raskulinecz [the album’s producer] brought this whole idea to us that we should look at our past and see what we can draw from it and not always try to run away from it. Sometimes you forget that those are your strengths. I think he opened our eyes a little bit to that…

JDB: We’ve stolen quite a bit from your music [laughter]. Synchronicity by The Police has a massive Rush influence, and there’s a song on the new Biffy Clyro album that’s just 2112. Does it ever annoy you when people lift your stuff? It annoys me.

GL: Really [laughs].

AL: I never think of it in those terms, but you know you can be subtly influenced by something you hear. I think we go through the same thing…

GL: I think we’ve written a couple of things that Jimi Hendrix did…

NW: I’m really influenced by Neil as a lyricist. When he joined, did you realise that he wrote words?

AL: We hoped he did [laughter].

GL: We didn’t find out until we were with him on that first tour. Originally, our old drummer [John Rutsey] was the lyricist. He wrote all the lyrics and he had this breakdown when we were recording. He decided that he hated all the lyrics and he tore them up the day before we were supposed to start the vocals, so I had to quickly write all those lyrics out right off the top of my head. So then when Neil joined the band, we didn’t know he was as literate as he is, or that he had an interest in doing that, and when we were on tour together Alex and I were like: “He reads a lot…’”

AL: He’s always got one of those things – what is it, a book?

GL: So we said: “Neil, have you ever thought about writing lyrics?” He said, no, but he’d love to try, and we were like: “Whew, great.” Because we did not want to do that job…

NW: You recorded in Rockfield studios in Wales. I was wondering if you had any memories of it? We recorded there, and were constantly saying things like "Closer To The Heart was recorded on this desk…"

GL: We went there for A Farewell To Kings and then went back for Hemispheres. We were there for months.

AL: It was a long, long, long, long time…

GL: With Hemispheres, we went early to Monmouth and rented a house. We wrote the whole album there, then we moved into the studio and we used up all our time. We still weren’t done, and then we had to go to London. We actually used our mixing time in London to finish all the vocals and everything, so we were way behind on that album…That was painful.

JDB: People we knew in the Valleys would go and try to find Rockfield just because you’d been there.

GL: Really? They were great people there, it was our first residential experience and our first experience of British television. In those days there was like, three- and-a-half channels…?

AL: Open University every morning when we were just going to bed.

GL: And waking up to the sound of cows mooing and sheep baa-ing outside.

NW: I think they’ve still got the same furniture there.

AL: I hope so.

NW: Getting technical, Geddy, how do you manage to play double-neck guitar, Moog, bass pedals and sing lead vocals at the same time?

JDB: We tried to use bass pedals and it was fucking impossible [laughter].

GL: Even now the thing I have to practice most before a tour is that choreography between the pedals and vocals and bass. That is the hardest part without question. If I could just play bass that would be a treat!

NW: Growing up, our view of the three Rush personalities was that Alex was the missing link, a renegade…

GL: Well, he’s a Serbian, so it is like the missing link, isn’t it?

NW: Geddy was organised, but a kind of rock, and Neil is an absolute mystery. Is there any accuracy in what we used to talk about in our bedrooms?

GL: Alex is certainly the most emotional and spontaneous of all of us. Neil’s not a mystery to us, we just see him as the big goof he really is [laughter]. And he’s very disciplined, he’s a total pro.

NW: He’s not a bad drummer either, is he?

GL: He’s getting pretty good.

AL: He’s getting better.

GL: I suppose to fans, because he removes himself from the public eye, he does have that enigma thing going on. I can see that.

NW: I remember watching the video for Tom Sawyer on Top Of The Pops. Did you realise with Moving Pictures that you’d gone overground, as it were?

AL: It was a turning point, definitely.

NW: Was it easy to make or was it quite painful?

GL: Permanent Waves was easy to make, and that was just before. Then we started having problems late in the Moving Pictures session because we were working on one of the first computerised consoles in Canada and it was starting to freak out. We had to shut down the mixing session for a while and they had to send someone from England to recalibrate the console.

AL: My recollection is of it being enjoyable. We had a lot of fun moments. I remember Witch Hunt, when we were outside in the freezing cold recording the mob scene for the intro…

GL: And that was the night John Lennon was shot. I remember that’s where we were, because we came in after recording that whole intro and it was all over the television.

NW: I’ve got a real soft spot for Grace Under Pressure.

AL: That was a very difficult record to make.

NW: I think I can hear the misery on there, that’s why I like it.

GL: That was also the first record we made without Terry Brown.

NW: I wanted to ask you about Terry, he seemed like a real part of your family in a way.

GL: He was our mentor, for sure. He taught us a lot. He taught us everything about making records back then, but after Signals I think we just felt we needed to learn somebody else’s way of doing things. We were able to guess what he would say before he would say it. When that happens, you need to move on.

AL: Yeah, we’d finished school. It was time to go.

NW: As someone who’s had bad experiences with producers, have you ever had any?

AL: We’ve had some difficult times with producers cause they didn’t happen to be a producer… [laughter]

GL: We worked with one producer on an album that I will not mention and the whole making of it was very difficult because we found out that the guy couldn’t really make a decision. That’s a hard thing to deal with when you have a producer and you go: “How was it?” And they go: “I don’t know, what did you think?”. I’m in here, you’re out there – you tell me!

JDB: Geddy, you’re one of the only singers I’ve met who’s in a similar position to me in that you’re mostly singing someone else’s lyrics. Did you have a complex at the start about doing it?

GL: It’s never just a natural experience. Once in a while there’s a lyric that comes along from Neil that I just agree with 100 per cent and I wish I’d written it, and then that song is never a problem for me to sing. But sometimes there are lyrics that are not exactly in sync with the way I think about things, and that’s where I have an issue.

But Neil gives me such incredible latitude with his lyrics. Like, he’ll give me three or four songs he’s written and if there’s only a line or two that I love in that, then I’ll go back in and tell him that these lines really speak to me and he’ll say: “Great.” And he’ll write that song around it.

JDB: I know that sometimes Nick or Richey [Edwards] will have given me a lyric that I found hard to perform. One lyric I couldn’t have sung, even on a basic emotional level…

GL: I have to believe in what Neil’s saying and as long as my impression is strong and I feel like I can sing it with conviction, that’s fine. But if I can’t sing it with conviction then it doesn’t matter, I can’t do it.

NW: In the Rock In Rio DVD there’s that most amazing scene where the crowd sing YYZ back at you.

GL: Natural Science, too. Now other audiences do it. We’ve noticed in the UK a lot of the crowds doing those same parts when we play those songs; it’s very sweet to see that.

NW: I think Rush are one of the few bands to never compromise. You’ve always seemed to have complete control of your destiny – with the new record, too. I think you’ve always kept your integrity…

GL: That means a lot, because for many years we failed in doing what we wanted to do. Then one day we succeeded. It felt so good and bought us some freedom. In the early days we got a lot of pressure from the record company. Then we made 2112 and thought, “Well, we’d rather die trying,” you know…

AL: And look where the record companies are now [laughter]…

GL: Kick a dog when it’s down, right?

This feature was originally published in Classic Rock issue 113, in December 2007.