When vocalist Kristoffer Rygg co-founded Ulver in 1993, he was a teenager infatuated with the danger and rawness of Norwegian black metal. “When you’re 15, 16, 17, that stuff has quite the draw,” he told this writer in 2020, “even though I never ventured into the murder business or the arson business.”

Instead, Rygg ventured into the genre-busting business. A trilogy of metal and Nordic folk releases offered everything he had to say in those spaces. So, after working as a studio apprentice and meeting late production/keyboard whizz Tore Ylwizaker, the musician reinvented Ulver as a fearless force, unafraid of industrial, progressive, ambient and even pop textures. The band now have an eclectic catalogue of 13 albums, with number 14 currently being released one single at a time.

Such an extensive discography can make it hard to know where to start. This is where we come in. Below, Hammer has condensed Ulver’s decades-long aural adventure into five standout works, representing this collective at their restless best.

The black metal trilogy (1995–1997)

Ulver’s black metal era consisted of just three albums, released via underground labels over a meagre two-year period. Yet, you can hear copycats of Bergtatt (1995), Kveldssanger (1996) and Nattens Madrigal (1997) emerging in the subgenre to this day. The way the debut played Nordic folk melodies on grotty electric guitars continues to be imitated, as does the vocals’ frequent rise from full-throated screeching to majestic, choral tones.

Ulver then quickly sliced their soundscape in half, furthering their folkish tendencies on Kveldssanger, where Nattens Madrigal embraced totally raw, high-speed, all-electric metal. It’s easy to see how the band felt like they’d accomplished their mission after this trilogy, as everything in their initial musical vocabulary got explored to its fullest extent. Thank fuck they returned refreshed, though, as their mastery of black metal’s characteristics left them nowhere to go except into far weirder and more interesting territory.

Perdition City (2000)

After Nattens Madrigal, Rygg worked as an apprentice at a recording studio in Oslo and met Ylwizaker, whose background was in post-punk as opposed to metal. He’d also developed an infatuation with electronic music. All these things ended up pulling Ulver away from metal on 1998’s Themes From William Blake’s The Marriage Of Heaven And Hell: an industrial double album as unrestrained as it was enormous. The band’s ‘metal’ members left afterwards, setting the stage for Perdition City to explore even further, while also proving more minimalist and cinematic.

Subtitled “Music To An Interior Film”, Perdition City was just that: a score for whatever images your mind conjured up while listening. Its combination of jazz, rock, electronic, ambient and Psycho samples was employed with dynamic intent, the idea of soundtracking movies very much an ambition for the group. This preoccupation would keep them from making another studio album for five years.

Blood Inside (2005)

Between 2000 and 2005, Ulver focussed on scoring art films and releasing ambient/electronic EPs. So, when the time came to make another formal album, they turned about face, pursuing a more maximalist and direct approach. Conventional instruments like the electric guitar and acoustic drums were reintegrated, the compositions were ratcheted into tight rock songs, and Rygg howled with unapologetic flamboyance.

Opener Dressed In Black introduced the re-reinvented Ulver, starting with expected synth and keyboard sounds before slowly expanding. Percussion crashed through, layer upon layer of singing was added on top, then the electronics built to near-symphonic levels of huge. Followup For The Love Of God made the cacophony even louder, falsetto vocals wailing as blasts of hammering percussion and all-consuming keyboards shot back and forth. Come the clamouring The Truth and riff-powered In The Red, Ulver felt like mavericks again, transformed just as listeners thought they’d finally settled down.

Shadows Of The Sun (2007)

Rygg characterised Blood Inside and successor Shadows Of The Sun as “flux and reflux” in a 2007 interview. After Ulver’s previous album had seen them eschew their atmospheric side with louder, sharper songs, they went back to smooth and mellow moods, albeit through different means. Shadows… wasn’t an instrumental/electronic effort like their early 2000s scores, instead sounding stripped-back and classical. The Oslo Session String Quartet was hired to lend cellos and violas, while any sense of exuberance got stripped away.

Such choice cuts as All The Love and the title track plodded forwards like hymns, no choruses to be found as Rygg sang with unbroken, melancholic depth. Eos had no percussion whatsoever, with only an ambient shimmer underpinning the haunting lyrics and a moving mantra to the Hindu god Shiva. It was all of personal significance for Rygg, who drew from his own experiences with depression and paranoia. Meanwhile, Ylwizaker studied classical composers for a year before making the music.

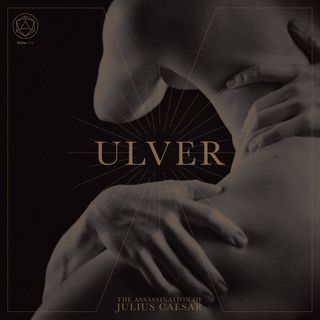

The Assassination Of Julius Caesar (2017)

Shadows… was followed by the more rock-inclined Wars Of The Roses, after which Ulver entered their most prolific era yet. They released four esoteric musical projects in five years, from psych-rock cover album Childhood’s End (2012) to ATGCLVLSSCAP (2016): an 80-minute, live-recorded drone piece. Then, out of nowhere, they were a synthpop band.

Released with only days’ notice in 2017, The Assassination Of Julius Caesar was the ultimate left turn in a career defined by left turns. Ulver, one of the least commercial bands on Earth, had pulled from Duran Duran and other 80s sensations to make eight nostalgic bangers. Nemoralia and So Falls The World flaunted irresistible choruses which drew from the iconography of Ancient Rome. Meanwhile, the likes of Rolling Stone projected vintage musical language into the future, making a nine-minute giant of electronic, gothic flair. Surprise and acclaim followed, and seven years on Ulver still inhabit this unforgettable yet still-experimental songwriting space.