The provocatively titled Lovehunter was the second full-length album from Whitesnake, the bluesy hard rockers formed in 1978 by David Coverdale following the dissolution of Deep Purple.

The singer had laid the group’s foundation with the late Bernie Marsden and Mick Moody on guitar, bassist Neil Murray and drummer David ‘Duck’ Dowle before his former Purple partner Jon Lord joined them on keyboards during the recording of their debut album, Trouble, the previous year.

Although Trouble had been a promising enough introductory statement, a more consistent set of songs aligned to escalating levels of internal chemistry and propelled Lovehunter on to a whole different plane.

Working at Clearwell Castle, the 18th-century estate in the Forest Of Dean where Purple had prepped for both Burn and Stormbringer, the band re-hired Purple’s producer of choice, Martin Birch, who had also overseen Trouble, to man the console of the Rolling Stones Mobile.

Later nicknamed ‘Headmaster’ by Iron Maiden, Birch was a serious guy but not without a sense of humour. Clearwell was said to be haunted, and Birch derived great amusement from piping spooky sounds into the band’s headphones as the tapes rolled.

Some of the album’s material, including Medicine Man, had been part-written and rehearsed, while other songs were composed in situ. Walking In The Shadow Of The Blues, which presented a textbook fusion of blues, hard rock and melody, was among those to fall into the former category.

It would become a pivotal early Whitesnake song and a stage favourite for many years to come. “Yeah, Shadow Of The Blues was brand new at Clearwell, which really pleased His Majesty no end,” Marsden told Classic Rock in 2019, laughing at the memory.

Marsden, who suggested the band should take a stab at Leon Russell’s Help Me Through The Day, had earmarked You And Me for inclusion on his own solo album, About Time Too (released the same year), but was persuaded by Coverdale to rewrite it for the group.

Enhancing its overall charm, the album ends with a short yet poignant sign-off, We Wish You Well, which to this day still sends concertgoers home with the audio equivalent of a warm, manly hug.

Whitesnake’s forays into the singles chart with the original versions of Fool For Your Loving and HereI Go Again – both later reworked for an MTV generation reboot – were still in the future, and the album’s main musical talking point was a salacious title track that had been worked on and then abandoned for Trouble.

Lovehunter saw the frontman barrel out his chest, proclaiming to be a ‘back-door man’ who’d ‘taken everything I could, but I’ve given all I can’ and promising to ‘give you all my loving, and use my tail on you’.

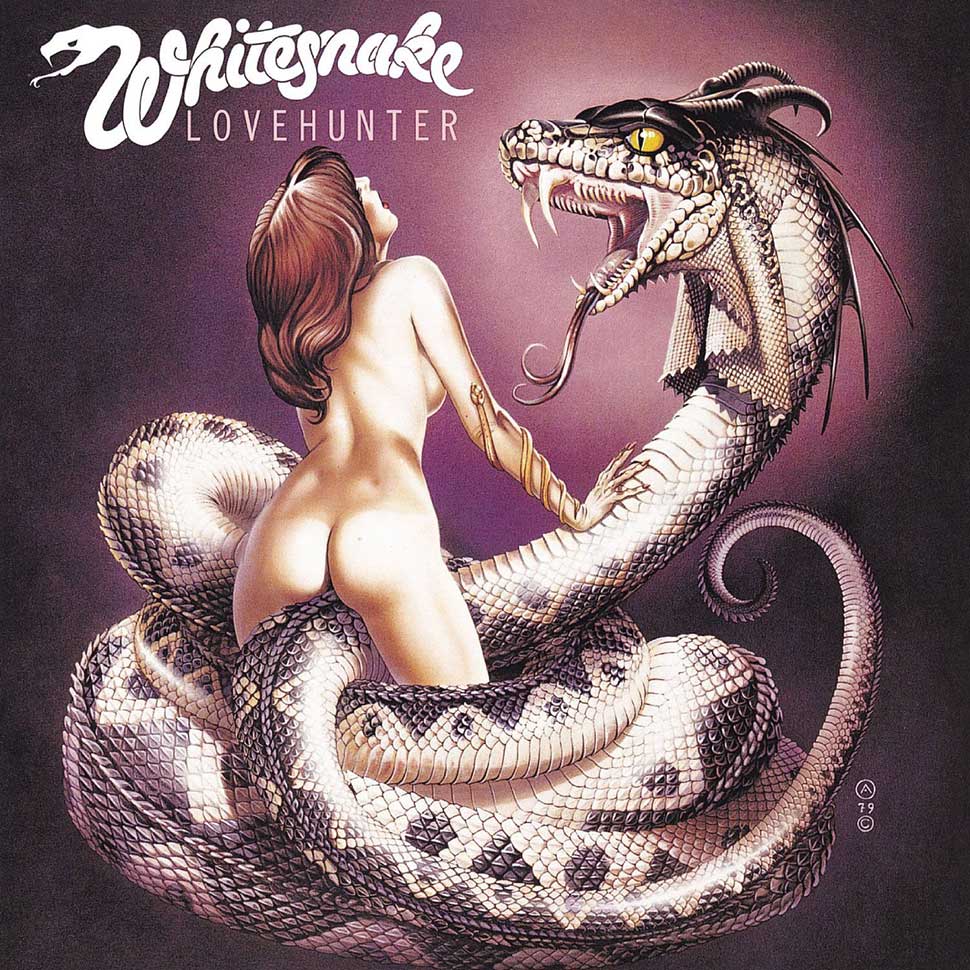

Coverdale had already inflamed the wrath of the so-called PC brigade with the previous album’s love- ’em-and-leave-’em lyrics, but Lovehunter – with a front-cover image of the rear view of a naked woman straddling the coils of a giant serpent – was about as subtle as a flying mallet. The image was drawn by the noted fantasy artist Chris Achilleos, whose work had sometimes appeared in Men Only.

“That’s where we heard about him,” Marsden said, smiling. “Somebody had one of those magazines, though I think he’d drawn a dragon or something.”

Coverdale later admitted that the Lovehunter sleeve was a knee-jerk response to those protesting about such imagery, and was conceived “just to piss them off even more”.

It certainly did that. The media campaign for Trouble had seen Coverdale cross swords with several journalists, including Robbi Millar of Sounds, on the subject of sexism. This time Sounds despatched a male writer, Phil Sutcliffe, although the outcome remained the same. Also a part of the interview, Marsden had felt compelled to ponder: “The sleeve is sexist, I have to admit that. Maybe we have done a wrong ’un. I don’t know.”

However, Coverdale was completely unrepentant. “We’re exercising the male fantasy of being a peacock and strutting,” he insisted to Sutcliffe. “We are playing cock-rock. We are bathing in innuendo.

"In America the sleeve has been banned for sexism and the album is going out in a brown paper bag,” he continued, before launching into an extraordinary rant: “I suggested stick-on panties for the boiler in the picture, but they seemed to think that would make it worse.”

Yes, he really did use the word ‘boiler’; four decades ago this was less of a hanging offence than in today’s more enlightened climate. And with the benefit of hindsight, Marsden happily admitted that the band’s wordplay and the Lovehunter sleeve were if not morally wrong, then a product of a bygone era.

"When you look at those things now, I can understand it,” he commented, referring to Whitesnake’s difficult relationship with the media. “Then again, we [the band’s instrumentalists] didn’t really take a lot of notice of the lyrics, though David wrote some magnificent ones like Ain’t Gonna Cry No More. What people didn’t realise was that what he wrote was completely tongue-in-cheek.”

When I sign the Lovehunter cover these days, I write the word ‘cheap’ instead of ‘cheers’ on the girl’s bum. Because that’s what it was

Bernie Marsden

Coverdale didn’t seem to realise that in principle Sutcliffe was on the band’s side. His story pointed out that the sleeve did Whitesnake a disservice, because most of Whitesnake’s songs “were not sexist but sexy” – that with the film Spinal Tap still five years away.

“David believed those things were all right [to say] because he’d convinced himself they were,” Marsden said. “That said, there were times when Jon [Lord] and I would see something he’d said in the Melody Maker or whatever and we’d wrinkle our noses. But David was the singer, and he did the interviews.”

It’s hard not to feel some sympathy for Coverdale, whose Rock & Roll Women seemed to lay his manifesto on a plate – he was looking for ‘a high-heeled double trouble backstage queen/Who gets what she wants and knows where she’s been’ .This was six of one and half a dozen of the other.

“That’s true, but I completely concur with some of the criticisms,” Marsden insisted. “David did believe in that stuff, because he had to front it [on stage], and maybe you have to give him credit for that. Though when I sign the Lovehunter cover these days, I write the word ‘cheap’ instead of ‘cheers’ on the girl’s bum. Because that’s what it was."

Lovehunter would prove to be Dave Dowle’s last record with the band. Coverdale explained to Sounds that the drummer was “unable to take constructive criticism”, elaborating with: “Whitesnake was getting to be a like a Spanish hotel – it looked good from the outside, but the foundations were a bit shaky.”

However, the way that Marsden remembers events, Dowle wasn’t fired, and in fact might even have elected to walk away from the job, effectively stepping aside for his replacement, former Purple drummer Ian Paice.

“Jon [Lord] had let it be known that Ian was available, and David Dowle was becoming pretty unhappy within the set-up,” Marsden explained. “He was a Londoner who didn’t like being away from his family, so being at Clearwell for around a month completely did him in. But [the split] was nothing musical. Listen to the record. If, as David claims, the foundations were becoming unreliable, then I certainly don’t hear that, not at all.”

Bringing in Paice, the “more primitive” drummer sought by Coverdale, served to reunite three-fifths of Deep Purple’s Mk III line-up in Whitesnake. This fact was not lost on the press, who began to suggest that Whitesnake’s line-up changes were nothing more than a shift towards Purple getting back together.

Marsden became so infuriated that he had a run of T-shirts made. “They had the Deep Purple logo on the front, plus the words: ‘No I wasn’t in…’,” he said with a laugh now. “Because of that, some of the press said: ‘Oh look, the first chink in the armour. Bernie Marden kicks back.’ But everyone in the band laughed their heads off.”

In the months leading up to the release of Lovehunter, Whitesnake had been one of the bands of the weekend at 1979’s Reading Festival. “We went down an absolute storm, and that made a big difference,” Marsden recalled fondly. “We sold a lot of records when it came out. Ian was yet to come, but Jon had already joined and it made us think: ‘Maybe we’re a bigger band than we thought.’”

Released in October ’79, Lovehunter became the band’s first Top 30 album in the UK. When it was released in Argentina, a chain-mail bikini bottom was airbrushed on to the female star of its sleeve, while for the US market a sticker was applied to conceal her posterior.

Although Lovehunter represented a massive step up from Trouble, talking in an interview years later Coverdale made the rather perplexing statement that Lovehunter would have made a very good EP.

“David really said that?!” Marsden asked, disbelievingly, before adding with a chuckle: “I don’t know which of its six tracks he would have taken off to make it happen. But albums are like your children – nothing is perfect. And once you’d made them, you can never go back.

"However, back in those days Whitesnake really was a collective. Now David does exactly what he likes. But back then we argued about things because they really mattered. It was a good, healthy, positive thing.

“And because of that the band got better and more successful with Ready An’ Willing [1980] and Come An’ Get It [’81],” Marsden concluded. “But Trouble and Lovehunter were still really good records, and for David to say that he doesn’t like his first and second born children… well, I think that’s a bit disrespectful, really.”