Who is the real Paul Stanley?

On stage he’s the sex-crazed Starchild, the Kiss icon who rock’n’rolls all night. Off stage he’s a home-builder, chef, and family man who has finally grown to accept himself...

You know you’re getting close to Paul Stanley’s house when your ears start to pop. That, of course, has nothing to do with the bombastic Kiss frontman’s piercing falsetto that has helped the band sell more than 100 million albums over the past four and a half decades. It’s because Stanley lives high up the treeline in the Santa Monica Mountains, in a villa that he’s fond of calling “the house that bad reviews built”.

And he’s right. Plenty of fans love Kiss, but critics don’t, bashing them ever since the band first hobbled out of their New York loft in 1973, wearing five-inch platforms, black fetish wear and greasy make-up, to begin their conquest of the restless hearts of suburban teens. For most fans, Kiss were always more than just a band. They were a state of mind, a place where feeling alienated was venerated, where boys were men, girls were groupies and nobody ever had to turn down the volume.

For their critics they were an irritant. They could never quite figure out why four (mostly) intelligent and somewhat erudite guys deliberately played dumb with their comic-book theatrics, musical simplicity and promise to ‘rock’n’roll all night and party every day’.

While Kiss embodied every single thing rock’n’roll was supposed to be, they were actively, albeit unofficially, barred from being inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, kept out until 15 years after their eligibility. Bestselling author and Creem magazine co‑founder Dave Marsh, a member of the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame nominating committee, huffed in 2011: “Kiss will never be a great band, and I have done my share to keep them off the ballot.”

Fortunately they had supporters such as Rage Against The Machine’s Tom Morello, who called himself “a noisy, fist-pounding advocate for years for Kiss to be in the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame”.

People listened, because in 2014, the band were inducted by Morello himself. Morello isn’t the only modern-day musician who claims he owes his career inspiration to Kiss, though. Garth Brooks has famously said that Kiss were his Beatles, while Dave Grohl has been a diehard fan for 40 years.

“These days I spend every morning before school with Paul Stanley in the parking lot of our kids’ fuckin’ elementary school,” Grohl revealed a while back. He confessed that the two talk about Zeppelin, Electric Ladyland, the rigours of touring and, of course, school fundraisers – like the one the Foo Fighters put together last October, and got Stanley on stage for a version of Zep’s Whole Lotta Love and the Stones’ It’s Only Rock’n’Roll (But I Like It).

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Back to Stanley’s house, which was once owned by raunchy American comic Redd Foxx. Stanley spotted it around the time the members of Kiss put their differences aside, slapped the make‑up back on and reunited for the Alive/Worldwide Tour in 1996, their first with all the original members since 1979’s Dynasty go-round. That 1996 tour, which no one thought would ever happen, grossed a whopping $143.7 million, their largest payday to date, and was the top-grossing rock tour that year.

With his part of the take from the 13-month tour, Paul Stanley purchased a Big Dipper-shaped slice of property, razed Foxx’s white stucco Mediterranean-style digs and began constructing his dream home, based on country houses he’d loved when he was in Italy.

By the time the landscape artists were planting the first cypress trees on the property, the Italian tiles were being laid around the turquoise swimming pool and the frescos were painted in the dining room, and a fan in Cincinnati, Ohio, threw his prosthetic leg on stage at a Kiss concert in the Riverside Stadium. (Without batting a kohl-rimmed eye, the band members signed the faux limb and threw it back to him.) When Kiss got to the Rainbow Theatre in London for the reunion tour’s final show – where Stanley burned his guitar before smashing it, a gesture full of meaning and ire – the rose bushes were being planted and the water was turned on in the fountains.

Now, 21 years later, Paul Stanley is comfortable as lord of the manor in his Tuscan dream. While baronial in scope and interior decoration, the 9,000-square-foot home has a rather cosy, lived-in look. Unlike many other rock icons, such as Rod Stewart and Tom Petty, whose palatial homes resemble the hushed hotel lobbies they’ve spent many of their better days in, Stanley’s house looks like the way his 19-year-old self might have imagined a rock star’s house should look, with huge wrought-iron candle holders, with tapers as thick as an elephant’s ankle; large, overstuffed furniture that can completely swallow you; chairs fit for a Tudor king; a marble fireplace tall enough to roast an entire boar in it; not to mention the leopard-spot carpeting (like the finish on the BC Rich custom guitar Stanley used on the Animalize tour) that covers an entire room. Pride of place goes to the Tiffany lamp he bought in 1978 for $70,000 after his blush of real success.

“I had just bought my first apartment in New York. I literally had no furniture, but I had that lamp and I thought I was the luckiest guy in the world – but now I know I am,” he says, sweeping an arm that seems to encompass the whole house, the grounds, maybe the entire universe.

The house is located in one of the most geographically desirable areas in this geographically desirable city. If you squint and look beyond the column-lined loggia you can see the Pacific Ocean. Look the other way and you can see the not-so-gentle S-curves of Mulholland Drive, where Hollywood thrill-seekers Steve McQueen and James Dean regularly careered around the two-lane highway’s legendary hairpin turns, sometimes with near-disastrous results.

The strip of road that Stanley calls home has been known as Bad Boy Drive for the past 30 years or so, thanks to the debauchery and sheer wantonness of a trio of hellraising stars: Marlon Brando, Jack Nicholson and Warren Beatty during his bachelor days. If this were two decades ago, the name would fit Stanley to a T. Old girlfriends still talk about his lack of fidelity. But then it wasn’t something he has ever tried to hide. For most of Kiss’s glory years there was a constant parade of Penthouse pets and Playboy centrefolds who scampered through his life and his bed.

“I remember I was with my mom and I was telling her a story about a girl I was going out with,” reminisces Stanley, sitting on the edge of one of his fawn-coloured velvet couches in his family room. “She didn’t seem to know who I was talking about, so I said: ‘You know,” so and so. ‘She’s blonde and has big boobs.’ She looked at me and said: ‘All your girlfriends are blonde and have big boobs.’

“I used to enjoy just pushing my parents’ buttons to let them know I’m living a life they would be aghast at,” he says laughing, “but apparently it stopped working.”

However, since meeting his second wife, Erin Sutton, at Ago’s, a fancy West Hollywood restaurant co-owned by Robert De Niro, Stanley stopped his womanising ways. The couple married in 2005 and have three children together. “Erin was just a godsend. I always say if I need proof of God, it was meeting her.”

As if on cue, Erin, 20 years his junior, walks into the sitting room, having just picked up their youngest child, five-year-old Emily Grace, from school. (Stanley’s brood also includes 22-year-old Evan, with his first wife Pam Bowen, 10-year-old Colin and eight-year-old Sarah.)

The couple usually go to together the same cardio barre exercise class, a punishing session where he’s often the only man. Stanley posted a couple of selfies of himself splayed out on a yoga mat: “Been doing cardio workouts with Erin in a class of women. Ego makes me push on. JEEZ! Why am I sweating like this?” Another Instagram groused: “10:30am exercise class is over. On the floor. Conclusion?? The waiting is NOT the hardest part. @tompetty #exercise.”

The first thing that strikes you about Paul Stanley is how thin he is. “Rock’n’roll is never kind to the fat boy,” he told me more than 20 years ago. At 65 he’s amended the credo a little, telling me: “No one wants to see a fat rock star in tights.”

Maybe not in any kind of leisurewear. On this cold and drizzling winter morning, he’s wearing black Levi’s 511s, a black V-neck T-shirt and patent leather dress shoes, and around his neck an atavistic silver charm that looks to have primitive talismanic power. “Is it from Chrome Hearts?” I ask, citing a status jewellery line, a favourite of celebs including Steven Tyler, Lenny Kravitz, Cher and Chanel head Karl Lagerfeld. “No!” he says aghast. “If you buy Chrome Hearts it means you’re making too much money.”

Stanley is rather circumspect – and careful – about his wealth. Unless he’s at a charity event or an awards show where he’s wearing Brioni or Varvatos, he dresses down in jeans, T-shirts and trainers – always with black soles. He does his own grocery shopping at the nearby Ralph’s, by no means a high-end supermarket, driving himself in an understated black SUV. There are photos of him in a beanie and a T-shirt, holding a Starbuck’s coffee in one hand and giving the photographer the finger with the other.

Despite the veneer of civility, the perfect teeth and the expensive sculpted haircut, there’s still much of the guy from Queens who wanted to be a rock star, like countless other pre-teens when they saw The Beatles on television for the first time. Stanley just happened to be one of the few who managed to pull it off, galvanised by the idea of success as a panacea to the self-worth issues he felt as a child. These were due largely to a birth defect called microtia. His right ear was misshapen and he was partially deaf on his right side, unable to determine the direction of sounds in his school classroom. He sank into a pit of despair and suffered constant taunting. While scoring high in IQ tests, he wasn’t able to hear what his teachers were saying so consequently did poorly in school. Called ‘Stanley, the one-eared monster’ by his classmates, he kept to himself and had few friends.

“It wasn’t like putting on a shirt you didn’t like and then going home to change,” he says. “I couldn’t go home and change this. I just had to live with it.”

Or at least until The Beatles and The Byrds came along, and a change in fashion that allowed men to wear their hair long.

For years, no one knew. Not even his bandmates in Kiss. “I think we can’t reveal our secrets until we’re comfortable enough to,” he says. “When you are, then the ultimate freedom comes from freeing yourself from the things that you hide.”

Stanley was halfway through his first run as the Phantom Of The Opera in 1999 when an audience member got in touch with him. She worked for an organisation in Canada called AboutFace that helped children with facial differences cope. Without knowing it, she intuited that the phantom was more than just a role for Stanley. After the two met, he admitted that he had a traumatising facial deformity, and by the end of their meeting had agreed to become a celebrity spokesperson for the organisation. He now helps raise funds for them and visits schools to speak to would-be bullies and detractors about classmates who might be similarly handicapped. And it was by doing this that his healing and self-acceptance really began.

“That’s when I realised the phantom was me,” he says earnestly. “That I was born to play it. It was a story of a scarred, deformed musician who hid behind a mask. I didn’t even realise that was why I was so drawn to the part, and when I did. It was a massive turning point for me. Everything in my life changed after that for the better.”

But with Paul Stanley, you can never tell. He’s rather parsimonious when doling out information, playing things close to the perfectly tailored vests he likes to wear. It wouldn’t be incorrect to say he’s still wearing a mask, just that now it’s invisible. He’s careful, appropriate, soft-spoken and articulate, polite and warm. Approaching friendly, but not quite getting there.

For him an interview is another performance. But then maybe it always was, and I was too blinded by being a private in the Kiss Army to notice; too paralysed by nerves the time I joined the band on stage for my breakout story, I Dreamed I Was Onstage With KISS In My Maidenform Bra. And, after all, it was Stanley who showed me how to hold my red guitar “low and sexy”.

My mind keeps screaming: ‘Where is that guy who used to whip up his audiences into an orgiastic frenzy, teasing and taunting, demanding that they say “rock’n’roll” like their life depended on rock’n’roll, when it was clear that his did?’ Then, dangling his lean, leather-booted legs over the lip of the stage, just out of reach of the grasping crowd, wiggling his ass and dancing away right out of their clutches. He later explained: “The reason I’ll throw myself at the audience is to see if they’ll take me.”

Now he knows they will. And that changed something in him. On stage he’s effusive and inappropriate. In his exaggerated New York accent, pitched way above his normal speaking voice, he asks, as a lifelong teetotaller: “How many of you people like to get high?” while stretching out the last syllable until it becomes a screech. Or prodding: “How many of you girls like to get licked?” Or emitting a huge scream, followed by: “I’ve got a feelin’, people! If y’all loosen up just a little bit we’re gonna get this place so hot we’re gonna have to call out… the Firehouse!”

Off stage he’s anything but that character. This is another guy. Sincere. Serious – very serious. Was it the make-up that gave him licence to become Jekyll to his own Hyde?

“No,” he replies firmly. “The years that we were out of make-up [1983-1996] were fine for me. I found them very satisfying because I got a chance to be out there without make-up, which I craved at that point.

“I think it was easier for me because my persona was one that wasn’t really defined by the make-up – it was embellished,” he explains, emphasising the last word. “To me, the make-up was just reinforcing what you were seeing and who I was. But the day we put the make-up back on before the reunion tour was magical. To look in the mirror and see that face again was empowering.”

Would it be fair to say you’ve integrated the Starchild and Paul Stanley?

“Totally,” he says, nodding his head.

But they were separate for a long time.

“Very much so. That’s why there are still bands and there are still performers who don’t want to go home, because they don’t have a home and because they need that mass adulation.”

But what about you? The Starchild needs the attention, but Paul Stanley doesn’t any more?

“That’s not really what I meant,” he replies stiffly, getting up to straighten one of the floor-to-ceiling drapes. “To a point it’s easier to live with the attention you get from being on stage all the time than to get your shit together and get your life in order. But if you do get your life in order, everything is enhanced.

“For as long as you’re on stage, it’s magical. But the disparity between being on stage and off stage, that’s where the problem comes in. So I see some other bands and I know why they’re out on tour – because they can’t stand being home. It’s much nicer to use one to enhance the other.”

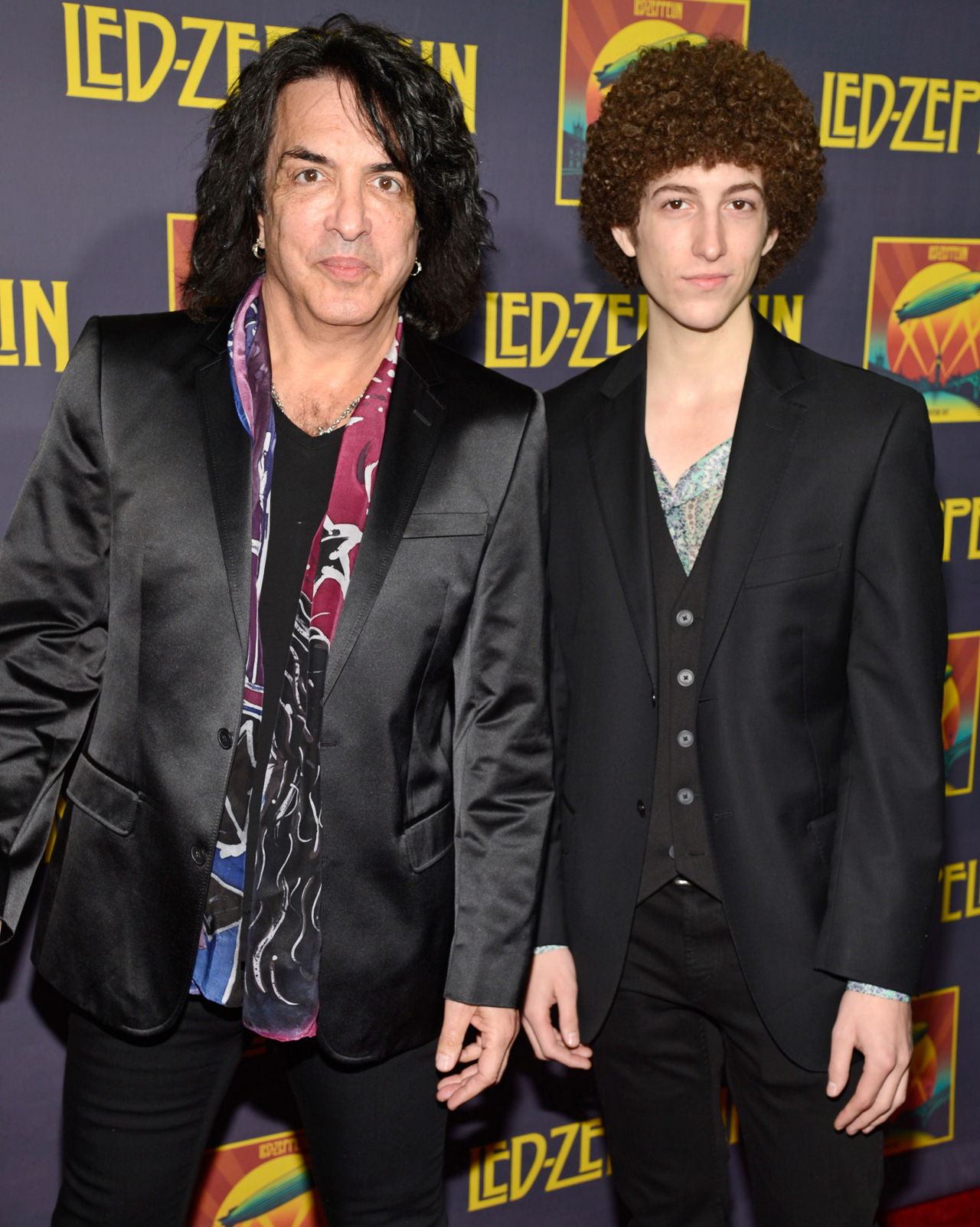

These days, Stanley doesn’t feel the need to tour as much. When he does, he makes sure he can take his brood, save for Evan, who lives in New York where he heads up his own band, The Dives. After the debacle of Kiss’s 2000 Farewell Tour with the original members, Stanley says there’s a slim-to-none chance that they will ever again re-form the band with the original line-up, despite the fact that last year he collaborated with former bandmate Ace Frehley in a video for a cover of Free’s Fire And Water, a track from guitarist Ace’s covers album Origins Vol. 1.

At the end of the second reunion tour in 2002, Stanley and Gene Simmons really intended to pull the plug on the band, until (and yes, the reason does sound somewhat unbelievable) an attendant at a car wash that Stanley frequents near his home told him they shouldn’t do it, and that maybe they should instead just consider it a farewell to Peter Criss and Ace Frehley. “I took that as a sign and that’s exactly what we did.”

Stanley also seems to be getting along better with Simmons now. He’s stopped saying things like: “Gene lives close by. His ego is so big I can see it from here.” Now his comments are much milder.

“Gene’s my brother. He lives right down the street. And we like each other so much that we stay out of each other’s way. As sickening as it might sound, we’re not beyond sending each other texts of appreciation. We both have the lives that perhaps we didn’t intend to in the beginning, but we both made it possible for us to reach the lives that make us happy. If you would have told him thirty, forty years ago where he’d wind up, he couldn’t comprehend it. But you have to keep moving forward. And you may find your destination is not where you intended.”

Stanley’s home is noticeably devoid of Kiss memorabilia, except for a Kiss pinball machine pushed against the far corner of the room. “We all play it. It’s awesome. I wouldn’t want any of that other stuff in the house, but this… I know who I am, what I’ve done. I don’t need to keep reminding myself.”

There are few other accoutrements of life as the lead singer of what was the number-one rock band in the world in 1977, according to a Gallup poll. Perched on an antique wooden occasional table are framed photos of Stanley, his family, Paul McCartney, and one of Stanley with Jimmy Page, his true musical hero, then as now; when his iPhone rings, the unmistakable first four notes of Led Zeppelin’s Good Times Bad Times slice through the deep silence of the room. “Did you hear that?” he asks.

In Stanley’s entryway is an abstract painting titled Crossroads that he painted himself. It’s stunningly good, and reminds one of Picasso’s African period, if the Spanish artist had used more primary colours instead of earth tones. “I painted one for Jimmy and it hangs in his entryway too,” Stanley says proudly.

We continue a short tour of the rest of his home. His patent leather shoes make a squeaking sound as he crosses from the carpet to hardwood floors, their glossy mirror finish trapping flecks of the early afternoon light. He catches me looking at them and says, a little defensively: “What? I like patent leather.” It’s a small, humanising moment.

Squeak, squeak, squeak, squeak. We move from the family room into a more formal living room with a gleaming black grand piano.

“Do you…” I begin to ask.

“No, I don’t know how to play,” he replies, anticipating my question and besting me in what’s beginning to feel like fast ping-pong, rather than a true interview.

We follow the natural curve of the house into a large dining room lit by a crystal chandelier, with a mural that Michelangelo could have painted – airy and celestial, with cherubs and clouds floating beatifically on a lemon-yellow background. On a massive formal dining room table that seems lifted from Game Of Thrones are the remains of a Monopoly game set up for two players, with no clear winner. A fitting game for the children of a man who is worth more than $200 million.

“No, no, my children aren’t spoiled,” Stanley counters. “Evan sold vegetables at a roadside stand and was a delivery boy for a deli. I had a conversation once with a very successful doctor and he asked me: ‘How do we get our children to have the thirst and the desire to succeed when they already have everything?’ I told him you can’t replicate your childhood. You can’t replicate your life, because it would be artificial. It’s like when your grandfather would say: ‘When I was your age I didn’t have shoes to go to school.’ Well, I have shoes. I didn’t grow up in a house like this – I was a cab driver – but it doesn’t mean that my children can’t have the values that will have them aspire to their own successes.”

Squeak, squeak, squeak, squeak…

As we move through the house, the high-ceilinged rooms spill into one another. There are no doors or divisions between them, it’s one lovely, sprawling space, ending at a bright, spacious kitchen with a restaurant-quality range. Pots and pans are stacked haphazardly in the cupboards. Drawers are a little ajar, there’s a pile of used plastic Ziploc bags in a corner of the counters, and a carved wooden highboy is stacked with papers.

The items are actually recognisable from the photos of meals that Stanley makes and posts on his Twitter account. Last autumn he posted: “Just winging dinner. No pun intended! Made Chicken Piccata but don’t know how.” Then: “No sauce? NO PROBLEM! Check out my pizza with olive oil, cherry tomatoes, parmigiana and rosemary. AWESOME!! @FoodNetwork @FoodChannel.”

In fact Stanley is a gourmet-standard chef, who cooks up prosciutto Brussels sprouts and chicken marinade on the Hallmark Channel, giving shout-outs on Twitter to Food Network chefs Scott Conant or Alex Guarnaschelli, or giving cooking demonstrations on Kiss Kruises.

“I’ve been cooking since I became a single dad [in 2001, after his divorce from actress Pam Bowen],” he says. “I’m pretty good at it. I’m good at Italian food and have a pizza oven outside.”

So good that there are videos of him stretching a disc of dough twice the size of his head, spinning it and tossing it four feet in the air. “My fingers have been everywhere,” he says, leering at the camera, “and they gave pleasure to a lot of people.”

It’s a reminder that if Kiss were superheroes, his special talent was the power of sex. Preening and strutting for audiences for the past 44 years – a shoulder drop here, a nipple pinch there – he was the Marilyn Monroe of rock frontmen.

But since 2012 there’s been more steak than sex sizzle in that mix. Or at least hamburger. Stanley and Gene Simmons became co-owners of Rock & Brews, a family-friendly restaurant chain that is a combination of sports bar, brew pub and concert hall, each boasting a Great Wall Of Rock bearing iconic rock art, and flatscreen televisions that continually stream some of rock’s greatest moments – Kiss concerts included.

Currently with 18 locations, from Hawaii to Mexico, there are plans to develop a destination casino and resort in Braman, Oklahoma, in partnership with American Indian tribe the Kaw Nation. At each of the openings, Stanley demonstrates his cooking acumen, making a pizza on the fly, all the while giving cooking tips.

So what’s your best tip?

“Cooking tip?” He looks flummoxed, taking a long minute to consider. “Oh my gosh. Balancing flavours. That applies to art. That applies to music. I’m a monkey at a typewriter when I’m cooking, but if you just keep tasting, you figure out where your balance is. The way you do anything is the way you do everything,” he says seriously.

There is a side of Paul Stanley that comes across like a motivational speaker. Okay, a big side. Perhaps much of that has come from overcoming his own demons – and that doesn’t mean Simmons, although there certainly were some intra-band dynamics that Stanley has dealt with over their 47-year-long partnership. Kiss were well into their twentieth year – and Stanley into almost the thirtieth year of his intermittent psychotherapy (that began when he was just 16) – before he really dealt with some of his self-esteem issues. He grew up in a household where his parents weren’t particularly effusive or affectionate, with an elder sister who clearly had emotional problems and developed some issues with drugs. But Stanley had to deal with something more tangible: that microtia condition.

“My struggle has always been to be the best me. So I’ve always been hard on myself. And maybe that’s the best way to accomplish what’s important to you. Because it’s so easy to please other people, but you go home every night and you’re the one who has to live with yourself. So compliments and attention are pretty hollow, and it only lasts as long as the person’s talking to you. My quest was always something different. And it wasn’t something that I needed to tell people. It was ongoing every day.”

But is the guy who started Kiss the same guy who answered the door today?

“Yeah. The heart’s always been the same. Growing up the way I did, I think I reached a point where I realised that who I patterned myself on, my parents, was a dead end that was only going to lead to my own demise in one way or another. So I had to go back to square one and learn… virtually I’ve had to learn to walk again, because I didn’t learn in a healthy way. So that was my struggle.

“I don’t say that for sympathy. We all have challenges, and maybe what people have responded to in my book [Stanley’s autobiography Face The Music: A Life Exposed] is realising that they’re not that different than I am. And I realised I wasn’t that different than them. Especially in the make-up.”

One of the first women to work in rock journalism, Jaan Uhelszki got her start alongside Lester Bangs, Ben Edmonds and Dave Marsh — considered the “dream team” of rock writing at Creem Magazine in the mid-1970s. Currently an Editor at Large at Relix, Uhelszki has published articles in NME, Mojo, Rolling Stone, USA Today, Classic Rock, Uncut and the San Francisco Chronicle. Her awards include Online Journalist of the Year and the National Feature Writer Award from the Music Journalist’s Association, and three Deems Taylor Awards. She is listed in Flavorwire’s 33 Women Music Critics You Need to Read and holds the dubious honour of being the only rock journalist who has ever performed in full costume and makeup with Kiss.