It’s February 1973 at the London apartment of Jimi Hendrix’s manager, Mike Jeffery. The only other person there is James ‘Tappy’ Wright, a softly-spoken Geordie who has been working for Mike since the early 60s in Newcastle when Jeffrey was a club owner and manager of The Animals. The night is wearing on, the ashtrays are full, the bourbon is flowing.

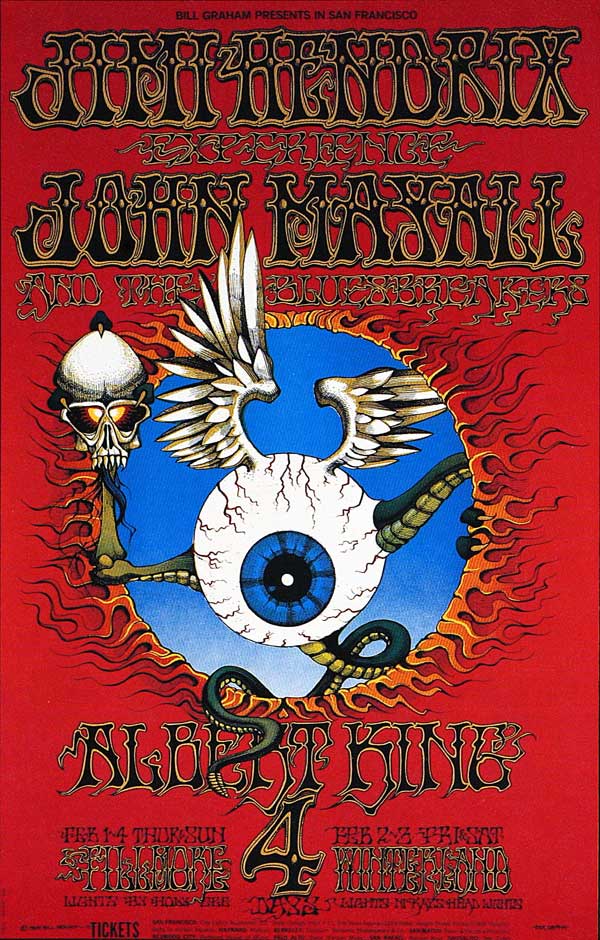

Mike owned the rights to Jimi Plays Berkeley, a film of Hendrix’s May 1970 concert at the Berkeley Community Center in San Franciso, widely regarded as among one of Jimi’s finest performances. After Jimi died, Mike had the idea that he would tour the film supported by live acts in his stable, Cat Mother and Jimmy and Vella. Because so many people who wanted to see Jimi never had the chance, watching him perform in a film coming out through a rock sound system in a cinema was the next best thing and according to Tappy, the tours of the UK and Europe were a huge success. So now they sit planning to take the idea to the States and this leads to a general reminiscence about Jimi and his last days.

“I can remember this as if it were yesterday,” says Tappy today, sitting in London’s Groucho club, remembering the night that Jeffery apparently confessed to Hendrix’s murder. “As we are talking, Mike began to get very agitated and pale. ‘I had no bloody choice, I had to do it’. ‘What are you talking about?’ ‘You know exactly what I’m talking about. It was either that or I’d be broke or dead’.

“I have to say that it did confirm suspicions that I had, that a lot of people had, only everybody was too scared to come forward and say anything. He was telling me, I didn’t ask and to be honest I really didn’t want to hear this.

”Mike gave away few details and Tappy didn’t press him further: “All he said was he got a few of his friends – I don’t know who they were, just some villains that Mike knew from up north and it was just booze down the windpipe. Like in that film Get Carter.

Barely a month later, Mike Jeffery was dead. Flying back from Majorca, his Iberian Airways DC-9 flight was in a mid-air collision over France. There were no survivors. Mike was terrified of flying and was in the habit of making several reservations at once and then choosing his flight at the last minute to escape the fates. But on 5th March 1973 his luck ran out and the full story behind his shocking confession died with him.

Tappy admits he sought no corroborative evidence then or since for Mike’s story: “Whoever else was involved was still out there and they might have thought Mike told me everything. So I kept my mouth shut, although I did tell my close friend, Bob Levine who was part of Jimi’s management team in New York. He told me to disappear.”

Eventually Tappy moved back up north and became a club owner. In the early 80s rock manager Rod Weinberg reformed The Animals and Tappy found himself back in the business. “I asked Tappy to get involved because I needed somebody to keep Eric and Chas apart,” says Rod. From their chats about the past came the idea for the book which they started in 1999.

So what motive could Mike Jeffery possibly have had for killing his major source of income and the biggest rock star in the world?

Flashback to September 1966. The Animals had broken up over the summer. Bassist Chas Chandler was sick of the road and wanted to move into production. Keith Richards’ girlfriend Linda Keith had persuaded Chas to come see a young guitar player strut his stuff down at the Café Wha in Greenwich Village. Impressed with what he saw, Chas tried to cut a deal for Jimi Hendrix even before he brought him back to the UK. Nobody was interested. He had no more luck in the early days in London as he showcased his new find around the club scene. Everyone was blown away. Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Pete Townshend were in collective shock, but still no done deals.

Chas quickly realised he needed a business partner. He turned to The Animals manager, Mike Jeffery. Nobody in the band had trusted Mike, believing he had devised an offshore tax scam simply as a way of stealing all their money. But John Hillman, the lawyer who administered the offshore company in the Bahamas called Yameta, is adamant that, “The Animals without Mike Jeffery were nothing.” Mike was a sharp operator with connections – and now Chas was on the other side, Mike’s side.

Mike Jeffery was born in south London in March 1933. The son of two postal workers, Mike had an average school career, but was quite sporty. He was called up for National Service in 1951 and then signed on as a full-time professional soldier. He was drafted into the Intelligence Corps and from then on, not surprisingly, his army career becomes a bit murky. He later told tales of undercover work in Egypt during the Suez Crisis in 1956, counter-espionage work against the Russians and general murder and mayhem in foreign parts.

Some of this Austin Powers – Man of Mystery routine may have been employed to impress (and frighten) the young musicians he later had under his wing. But his father Frank did say that Mike could speak fluent Russian, that much of his army career was spent in ‘civvies’ and that when he was at home, he rarely spoke about what he did.

But probably his crowning achievement in the service of Queen and Country, was to make serious money selling old newspapers to British soldiers stationed in Egypt. Troops abroad are always desperate for news from home. Mike found out that in Cairo (off limits to soldiers) newspapers were on sale that were only a few days old. Strictly against the rules, he commandeered a truck and began shipping piles of papers back to the base. He was caught, but cut his commanding officer a slice of the action and still had enough money to start up in Newcastle as a club owner, but not before he earned himself a degree at Newcastle University. So no stranger to danger, Mike proved himself intelligent, charming and street-smart.

In October 1966, Jimi, Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell signed a production contract with Chas and Mike, but on 1st December, Jimi alone signed a four year management contract with Mike. Not only were Noel and Mitch excluded – even Chas’ name didn’t appear until some time later. Right from the outset, Noel and Mitch were only ever regarded by Mike and Yameta as ‘employees’ and whatever Jimi might have said to them verbally, this state of affairs was reflected in the contracts.

For Mike, Jimi was the star and he wanted as few obstacles in the way of his investment as possible. Eventually they signed to Track Records in the UK, but Mike’s big coup was signing with Warner Brothers in January 1967. Aside from the recording contract itself, he negotiated a $20,000 promotion budget, unheard of for an unknown artist’s debut album, and he wangled an exclusion clause for any soundtrack recordings – something Warners would regret later.

On top of that, Warners agreed not to sign Jimi directly, but instead to sign for the services of Yameta which contracted to supply the ‘master recordings of Jimi Hendrix or the Jimi Hendrix Experience’ to Warners – and in doing so Yameta retained ‘exclusive and perpetual ownership of all masters recorded’. Not even The Beatles or the Stones owned their masters.

So with the substantial backing of a major US label, the Jimi Hendrix Rock Machine began to roll. Like Cream, the band spent more and more time in the States in search of the big bucks. The tours got longer, the concert fees rose, especially when Mike arranged for self-promotion of the band. Instead of dealing with dozens of different promoters all over the States, they dealt with a handful and paid them a percentage to promote the band. And he also wised-up very early on, to the earning power of merchandising – so more cash for the Experience coffers.

But by mid-1968, cracks were appearing in the organisation. Jimi knew he had Chas and Mike to thank for everything, but he was beginning to resent what he saw as Chas’ grip on his creativity. This came to a head during the recording of Electric Ladyland at the Record Plant in New York where Jimi was bringing in extra musicians to move away from the trio format.

Chas also got cheesed off about the drugs, especially LSD – and the growing band of groupies and hangers-on that infested the recording sessions. Chas decided to cut his ties as Jimi’s producer and went back to England, although for the time being, he retained his management interests. Jimi too was getting tired of Mike’s insistence on the need for constant touring – and moreover, the audience expectation that he would smash his amps or set fire to the guitar and the general boredom of playing the same songs every night. As he said later, he was fed up ‘playing the clown’.

Matters came to a head in the summer of 1969. The band’s performances became unpredictable depending on Jimi’s mood. Sometimes exhilarating and powerful, other times scrappy and ill-prepared with Jimi, Noel and Mitch hardly looking at each other. Noel left, Billy Cox was brought in and Jimi repaired to a rented house in Shokan, upstate New York to consider the future.

Although Mitch stayed on, Jimi began talking about Sky Church Music and gathered around him a whole group of new musicians of varying quality who played a patchy performance at Woodstock in front of the 30,000 people left on the Monday morning after everybody had gone home. Then Jimi went off the road and Mike Jeffery went nuts. Despite all the success, the cash was running out.

Although Mike had struck great recording deals, actually getting the money out of the record companies was the devil’s own job – they were always months or even years in arrears. So the real money was in touring – often thousands of dollars in suitcases and paper bags. But once Jimi left the Woodstock stage on 18th August 1969, he turned his back on touring until 25th April 1970 and the start of the Cry Of Love tour.

So the income was falling while the expenses were going off the radar. Jimi had no concerns for studio costs – he spent hours and hours just jamming and experimenting. Electric Ladyland alone cost $60,000. The band always spent heavily; limos, hotels, paying the bills for the damaged and the doomed who hung round Jimi’s neck, and who he could never refuse. He loved fast cars (although he was as blind as a bat) and one weekend bought nine guitars.

Mike was no stranger to spending either. As a character on the music scene, he was always felt something of an outsider. With his perennial prescription dark glasses and long black coat, he cultivated an air of menace, but he desperately wanted to be accepted among the American rock management elite, men like Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman. Partly as a way of getting closer to Jimi, he took on more of the hippy look and dropped lots of acid. In the summer of ’69, he bought an expensive house among the hip rock community in upstate New York and rented the house at Shokan for Jimi.

Then there was the financial black hole that was Electric Lady Studios. Mike had great success as a club owner both in the UK and Spain and tried to persuade Jimi to invest in a club in New York. Eventually this evolved into the idea of building a state of the art studio. Nice idea, shame about the location. In his book, Tappy recalls that ‘New York’s Eighth Street was right in the heart of Mafia territory; there were already four Italian clubs in the neighbourhood and the mob were not keen of having a rock star with Jimi’s reputation setting up shop in their midst and bringing a lot of unwanted attention into their area’.

Against that backdrop, there were endless problems getting the necessary building permits and then the site was flooded after they discovered they were building right on top of an underground river. And as shrewd as Mike might have been, he could also be impulsive. When it came to equipping the studio, instead of trying to arrange instalment plans for purchasing, attorney Howard Krantz says ‘Jeffery would just…buy the item outright’ adding to the cash flow problems.

So even though Mike secured a whopping loan from Warner’s, the original budget of $500,000 soon became a distant memory. Mike took the very dangerous step of borrowing money from the Mob. Bob Levine, who had worked for Sinatra, knew these guys and would act as the go-between. Tappy says he would “drive up to these big houses with gates, just like you see in the movies. Bob would tell me to wait in the car and then he’d come out with a package.”

The Godfather and The Sopranos have embedded gangsters in our popular mythology, so it is easy to forget that the Mafia are real and really do hurt people who cross them. Added to which Mike had left some unfinished business in London: Electric Lady studio manager Jim Marron remembers Jeffery telling him he owed someone $20,000: “They sent a guy over to kill [Mike] if he didn’t pay. That won his respect” – and he paid up.

And if that wasn’t enough, he had the American Inland Revenue Service (IRS) on his tail. Jimi never benefited from the Yameta tax haven because he was a US citizen; only UK citizens could afford paying tax in this way. Nor could Mike legally bring in any money from the Bahamas without the IRS getting their chunk. So Bob Levine recalls Mike’s assistants Trixie Sullivan and Kathy Eberth, arriving in New York with wodges of cash stuffed in bras and boots. The IRS was threatening to impound Electric Lady if Mike didn’t start making some regular payments. So he was treading a very fine line financially and was perpetually in need of cash injections to keep the boat afloat.

“Forward planning was not his strong suit, says concert promoter Ron Terry: “[Mike] planned from minute to minute. If he was broke, he reacted and that put pressure on his artist.”

Mike was also becoming very concerned not only about his worsening relationship with Jimi, but about those he saw as posing a threat to his position and his income. The music business was and still is, a hotbed of suspicion and paranoia. Maybe because of his involvement in Cold War activities, Mike’s sense of paranoia was more finely tuned than most. He was always wary of those who were much closer to Jimi than he would ever be and often tried to engineer ways of dividing and ruling.

Early on, he applied this technique to Chas and Record Plant staff like producer Eddie Kramer and engineer Gary Kellgren. But from 1969, Mike’s paranoia became more focused and intense. He even bugged Bob Levine’s office to keep track of what was going on, so distant was he feeling from Jimi and his circle. The band’s PR agent in the States, Michael Goldstein observed that Mike “would stop at nothing to ensure the success of his artists, but he couldn’t relate to them personally”.

Mike was very angry that Jimi refused to tour and blamed much of this on his renewed relationship with drummer Buddy Miles. To compound the crime, Jimi was working at the Record Plant with a new producer, Alan Douglas. Jimi had met Douglas through Devon Wilson, a notorious New York groupie who had a strange and rather unhealthy relationship with Jimi. Douglas was essentially a jazz producer who also had interests in films and books and Jimi quite liked his more New York bohemian, laid-back attitude.

But the recording sessions were not very fruitful and Alan Douglas was no match for Mike Jeffery, so much so that Alan wrote to Jimi in December 1969 saying he didn’t want to produce him any more. Still Jimi pressed on with plans for a new band with Buddy and bassist Billy Cox. Without Mike’s permission, the Band Of Gypsys played two dates at Fillmore East over New Year 1970, before Mike intervened, not only firing Buddy, but insisting that Jimi reform the Experience. Noel Redding was put on standby, but eventually The Cry Of Love tour kicked off with Billy Cox on bass and Mitch Mitchell.

The US tour was a good money-spinner, but still Mike had mounting debt. A critical element in the story is whether or not Mike had taken out an insurance policy on Jimi’s life. When Warner Brothers concluded a whole new set of agreements with Jimi in 1968, they took out an insurance policy, something which had become standard practice since the death of Otis Redding in 1967. Mike also prepared a similar policy and the document was in with a whole pile of concert contracts waiting for signature while they were in Hawaii filming Rainbow Bridge. Bob Levine spotted it and says he warned Jimi not to sign it; Tappy says he did.

Although from Mike’s point of view, Jimi was back on track, their relationship was souring by the day. Jimi was incensed that by forcing him to fire Buddy, he was now interfering in the creative side, something he had never done before. Mike now had one eye on the calendar – his contract with Jimi expired on 1st December 1970 and he became increasingly convinced that Jimi would jump ship.

With Electric Lady Studio at least partially open, Jimi had been working there for about a month. The very last thing he wanted to do was more touring, but he signed contracts to tour Europe in the autumn of 1970. A lacklustre performance at the Isle of Wight Festival was followed by a disastrous show in Arhus, Denmark, which was stopped after only a couple of songs. Jimi was still reeling from the effects of a handful of unidentified pills he had taken earlier just to block the misery of his situation. Worse was to follow in Germany on the Isle of Fehmarn where the atrocious weather and warring Hell’s Angels encapsulated the sorry mess of Jimi’s faltering career.

So Mike knew the clock was running out on his contract with Jimi. He had a mountain of debt which included two creditors you didn’t mess with – the Mafia and the IRS. But while it is true that Mike’s management contract with Jimi expired at the end of 1970, Mike still had quite an investment in Jim’s career. He had a half-share in the studio, various considerations as a result of the new deal struck by Warners with Jimi in 1968 and because of that little exclusion clause from ’67, had rights over two films, Jimi Plays Berkeley and Rainbow Bridge.

And while Jimi might have made a lot of noise about finding a new manager, who could that have been? The only name ever mooted was Alan Douglas and Jimi knew full well that Alan was not even close to being as effective as Mike. So it needed to be a major player who was also prepared to take on Mike Jeffery with all that might entail. That said, if Mike had lost Jimi, he would have lost the share of the concert revenue, which as we have seen, was the most immediate and lucrative cash cow. And given the level of Mike’s paranoia over money and Jimi, it was enough that he believed it. He might have calculated that Jimi Hendrix was worth more to him dead than alive – but did he engineer it?

The key to the last few hours of Jimi’s life lies with the testimony of Monika Dannemann. Born into a wealthy German family, Monika was a talented artist whose career as a skater was cut short by injury. She first met Jimi very briefly in Germany in early ’69 and not again until a few days before his death – although she claimed that Jimi kept in touch, writing her letters she refused to let anybody see.

I interviewed Monika in 1989, for my biography Electric Gypsy, travelling down to Seaford on the south coast of England. Her house was situated in a quiet, respectable street. She opened the door and there she stood looking exactly as she did the day Jimi died: striking blonde hair, heavily made up, wearing a crushed velvet dress and a jangle of jewellery. The sense that time had stood still for Monika was underlined when I went inside. The walls were covered in her artwork – every painting featured Jimi Hendrix. The house was a shrine. She was very friendly and, in her quiet way, told me the same story she told the coroner at Jimi’s inquest and subsequently all the other journalists and writers who over the past 20 years had tried to uncover what happened.

The essence of her story was this. Jimi was booked into the Cumberland Hotel near Marble Arch, but was actually saying with Monika in the basement flat of the Samarkand Hotel about 10 minutes drive away. During the afternoon of 17th September, they went with some people they’d just met to a flat near Baker Street. They returned to the Samarkand around 8.30pm and stayed there until the early hours of the morning when Jimi asked to be driven to another flat not far from the Cumberland Hotel in order to tell the perennially jealous Devon Wilson, who had flown in with Alan Douglas and his wife, that he was now engaged to be married.

Monika dropped Jimi off, came back about 30 minutes later and they returned to the Samarkand about 3am. They talked, Monika made Jimi a sandwich. They got into bed about 6am, Monika took a sleeping pill and fell asleep about a hour later. Jimi was still awake and she didn’t see him take any pills. She said she woke at 10am, saw Jimi was asleep and she went out to get some cigarettes. When she came back about 15 minutes later, she noticed Jimi had been sick and she couldn’t wake him up.

Not knowing who Jimi’s doctor was, she made some phone calls to Jimi’s friends, eventually reaching Eric Burdon who told her to call an ambulance. That was 11.18am. It arrived nine minutes later. She said that the ambulance drivers were very relaxed, no blue lights, and she travelled with Jimi in the ambulance to St Mary Abbott’s Hospital. Monika waited around and was eventually told by a nurse that Jimi was dead. The main thrust of her story was to blame the medical staff for his death, in particular the ambulance drivers, who she said had Jimi upright all the time.

I knew what Monika would say and so I had little cause to question any of it – until I went down to the hospital. I checked the hospital admissions register for that day, 18th August 1970, but could find no record of Jimi’s admission. I questioned Walter Price, a hospital porter who had been on duty that day.

“Jimi was never admitted,” he told me. “He was taken straight to the morgue.”

What he said was not entirely accurate, but doubt now crept in about Monika’s story. Checking back on her past statements, the bare bones of her story remained, but her actions and the timings altered with each telling. The discovery of those inconsistencies began a chain of events that ended not only in a much clearer picture of what happened, but a demolition of Monika’s story. She vainly fought back with threats of legal action against anybody – including me – who doubted her word.

As Tappy makes clear in his book, and confirmed by everybody in Jimi’s orbit – he regularly fell in love with ‘the woman of his dreams’, showering her with intimate whisperings and promises of undying love. Maybe sometimes he believed it himself, but mostly Jimi was charming his way to sex. It fell to Monika to be the last woman Jimi would ever woo and she convinced herself that he was sincere about marrying her and setting up home in England.

By common consent, the only woman who Jimi genuinely cared about – and who cared about him without any ulterior motive – was Kathy Etchingham. (“I wish they’d stayed together,” says Tappy. “Jimi might still be alive today.”) Jimi and Kathy lived together with Chas and his wife when Jimi first arrived well before he was famous – and later shared a flat together in Mayfair. And it was Kathy in the early 90s, aided by Mitch Mitchell’s wife Dee, who took on the task of uncovering the circumstances of Jimi’s death.

Incredibly neither the ambulance drivers, nor the police who attended the 999 call nor the doctors who did actually go through the motions of trying to revive Jimi in the hospital, were ever called to give evidence. For reasons best known to himself, the Coroner Gavin Thurston, just wanted this done and dusted as quickly as possible. The cause of death was cited as inhalation of vomit caused by barbiturate intoxication and with no evidence of foul play or suicide – Thurston declared an open verdict.

Kathy and Dee tracked down all these people and others besides. They gathered so much new evidence that the Attorney General ordered a police investigation. As it happened, a number of those who were happy to speak privately to Kathy either wanted nothing to do with the police or changed their stories for fear of publicity. So the inquest was not re-opened, but their testimonies stand. And so the story now looks like this.

Monika and Jimi did go the flat of some complete strangers in the afternoon, but Jimi stayed far longer than Monika wanted to, enjoying the attentions of the young women who were there and when they eventually left around 10.40pm, the owner of the flat Phillip Harvey said that Monika went crazy and was screaming and shouting at Jimi all the way out in the street. Later she did take Jimi to a party, but he was there much longer than 30 minutes, probably a good few hours. It was a flat belonging to a businessman with links to Track Records, Peter Cameron. Others present included Devon Wilson, Alan Douglas and his wife Stella. Monika came back to collect Jimi – he told Stella to get rid of her. But Monika kicked up such a stink that he had to leave.

When Eric Burdon asked Monika why she hadn’t called an ambulance, she said that she was scared because there were drugs in the room. So first on the scene was Eric’s roadie Terry Slater who told Kathy that he and Monika cleared out the flat, going across the road to some adjacent gardens where they buried the drugs. Meanwhile the ambulance drivers arrived to find Jimi dead and alone in the room. Following procedure they tried to resuscitate him in the ambulance, but he was clearly gone and this would explain why they were so relaxed and didn’t rush through the streets. Terry said that he and Monica viewed all this from across the street. The doctors at the hospital also tried resuscitation, but they could see it was hopeless. Jimi had been dead for hours.

Every time Monika told the story, critical details changed; the time they went to sleep, when she got up, whether or not she went out for cigarettes and so on. It transpired Jimi had swallowed nine of Monika’s German sleeping tablets, the equivalent of 18 times the recommended dose. And this is what killed him. Maybe she blamed herself for leaving them lying around. Maybe she felt guilty if Jimi had taken all those pills so he could escape from her constant nagging. Or as she told Terry Slater, maybe she was just scared.

Here was a 22 year-old white girl, a stranger in a strange land, from a wealthy background with a very conservative father, caught in a bedroom full of drugs with a world famous black musician. Could it be that on discovering Jimi dead she panicked and fled the hotel, and that all her strange behaviour and inconsistent stories were the product of covering-up this moment of weakness?

The problem was made worse for Monika over the years because she told everybody about not calling the ambulance immediately. So it became the wisdom among fans and other musicians that Jimi died because she delayed.

And where was Mike Jeffery while all this was going on? He was definitely in London on Sunday 13th September to visit Danny Halpern at Track Records. By all accounts he was desperate to find Jimi to discuss an upcoming court case concerning claims that Jimi had signed a deal with PPX Records before he signed with Chas and Mike. Did Mike stay in London? No, said both his assistant Trixie Sullivan and Jim Marron who both maintained Mike was in Majorca when the news came through.

However Bob Levine tells a different story. Interviewed by writer John McDermott he said that it took a week after Jimi’s death for Mike to call the New York office pretending that he had only just found out; “but I knew he was lying because I had spoken to people who saw him at a party Track Records had staged in London the night before Hendrix died”. And who were these people? According to Bob the very same people that had been at the flat of Peter Cameron – the man with links to Track Records – where Jimi had been seen that same evening: Devon Wilson and Alan and Stella Douglas. Could this be one and the same party – with Mike arriving and leaving early – and Jimi turning up much later?

As deep as Kathy and Dee were able to dig, there are still two significant and unexplained aspects to Jimi’s death. The first is that he was found fully clothed on top of the bed. Every version of Monika’s story has them going to bed together which by any normal interpretation means getting undressed and pulling back the covers.

The second point is that both the ambulance drivers and the doctor who attended Jimi at the hospital say that Jimi was in a real mess. Dr John Bannister was the surgical registrar on duty that day. When Dr Bannister read my book he wrote to me from Australia: “The very striking memory of this event,” he wrote, “was the considerable amount of alcohol in his larynx and pharynx… I recall vividly the large amounts of red wine that oozed from his stomach and his lungs.”

Yet the toxicology report revealed an alcohol blood level equivalent to about four pints of beer – and in any case, Jimi had an unusually low tolerance to alcohol. Once when he’d had a bit too much, he totally trashed a hotel bedroom. Earlier that month in Sweden, Jimi had swallowed pills, but there was no alcohol involved. However inconsistent her testimony, nothing Monika said suggested that Jimi had drunk a lot of wine, nor had he done so earlier in the evening. And there was no mention of empty wine bottles in the room. So where did it come from?

The open verdict came as a great relief to both Warner Brothers and Mike. If the verdict in any way suggested suicide, foul play or that Jimi had somehow contributed to his own death by reckless behaviour, then the insurance companies would have refused to pay out. In fact while the new police investigation was under way, the BBC tracked down the original insurance investigator who looked into Jimi’s death who confirmed that he had been looking for ways not to pay, but refused to reveal the contents of his files.

On the strength of a poem written by Jimi before he died, a very stoned Eric Burdon went on British television to declare that Jimi had died by suicide which brought a stern warning from Warner Brothers to shut up or else. And if Mike was convinced he’d lose Jimi, as Noel Redding pointed out later, his death was very convenient for Mike’s health and well-being. Tappy says he was able to clear all his debts and moreover, offer Jimi’s father Al, the sole beneficiary of Jimi’s estate, nearly $250,000 for Jimi’s half-share in Electric Lady studios.

There was a curious epilogue involving Monika and Mike. In the immediate aftermath of Jimi’s death, there were plenty of rumours flying around that Mike had been involved. In her book of artwork published in 1995, Monika wrote that even so, when she was in New York at the end of February 1971, she went to see Mike at Electric Lady studio – the man who everybody told her would do anything to buy silence. All they seemed to speak about was the possibility that Mike could become her manager to promote her artwork. She says that she specifically asked Mike to come to her to hotel room to ‘discuss things privately.’ Monika wrote that she resisted Mike’s offers and flew off to Seattle. But why did she seek him out in the first place?

Jimi’s premature death aged 27 was followed in the years to come, by the deaths of other key figures who died before their time. Always battling against heroin addiction, Devon Wilson fell to her death in mysterious circumstances from the Chelsea Hotel in February 1971 while Mike Jeffery died aged 39 in 1973. For Noel and Mitch, it was always a case of ‘what do you after playing in the Jimi Hendrix Experience?’ The answer was ‘not much’ and although Mitch fared better than Noel, both drank heavily as they slipped rapidly into obscurity. Noel died aged 57 in May 2003, Mitch followed in 2009 aged 61. Chas Chandler was also only 57 when he succumbed to a heart attack in July 1996, the same fate which later struck down Hendrix historian Tony Brown also in his fifties, who more fully documented the events leading up to Jimi’s death.

And what of Monika? As her story was crumbling in the face of new evidence, she made one accusation too many and Kathy Etchingham obtained a court order banning her from telling any more lies to reporters about Kathy and her investigation. Monika breached the order and had to face Kathy in open court. She was found guilty of contempt of court on Wednesday April 3, 1966. Always regarded as mentality quite frail – and liable for £30,000 in costs – two days later she died by suicide, her body found in a fume-filled Mercedes at her home in Seaford where I’d interviewed her seven years before. (There was no suicide note and predictably some – including her partner, guitarist Uli Jon Roth – speculated that she too was murdered.)

There may well be somebody out there who knows exactly what happened to Jimi Hendrix between 4am and 8am on Thursday 18th September 1970. And although the inquest was not re-opened, the case remains open. There is no statute of limitations on murder.

Rock Roadie by James ‘Tappy’ Wright and Rod Weinberg was published by JR Books in 2009. Harry Shapiro’s Jimi Hendrix – Electric Gypsy was published in 1990 and shortlisted for the Ralph J. Gleason music book prize.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 135, in July 2009.