But how far was too far? And who, exactly, was Ziggy? And why, 50 years after its release, does this particular album most commonly define David Bowie in the public’s imagination? Surely the songs on the earlier Hunky Dory were more sophisticated and the later works riskier and more experimental?

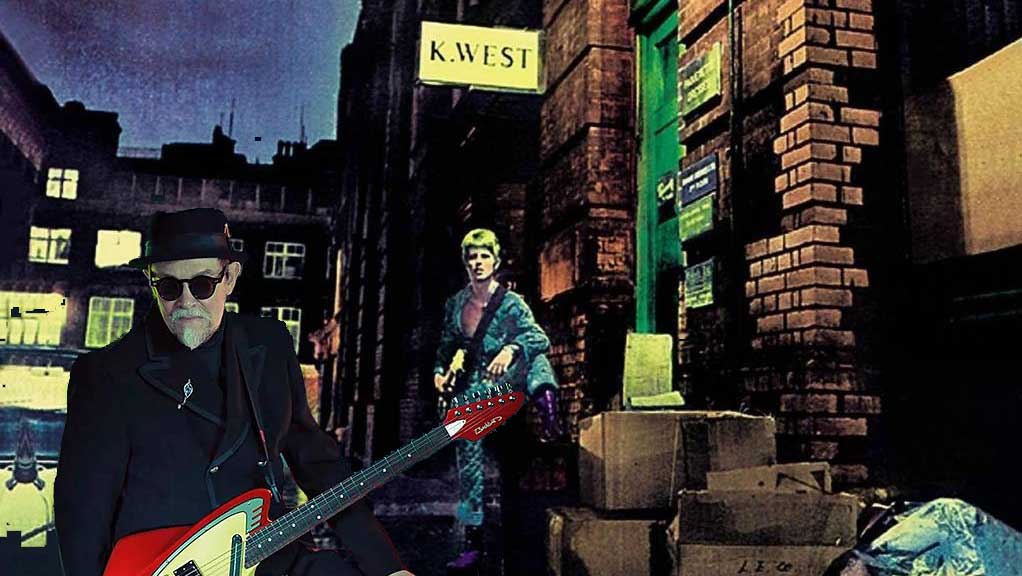

50 years ago, most of us thought that David Bowie epitomised Ziggy Stardust, even though the songs told the tale from an observer’s point of view rather than in the first person. And while David did sometimes strum an acoustic guitar on stage, the man who really took the guitar on a trip in The Spiders From Mars was the brilliantly gifted Mick Ronson.

Mick, like myself, was a Yorkshireman rather than a Martian – though apparently some Southerners still can’t tell the difference between Mars and Hull. So, does this mean that Mick was Ziggy? History has it that Ziggy was based on Vince Taylor, an obscure English rock’n’roller who believed himself to be both God and an alien. (Don’t laugh, we’ve all been there.) Another possible inspiration was eccentric psychobilly singer The Legendary Stardust Cowboy and, as some stories tell, Ziggy also happened to be the name of a tailor’s shop Bowie knew of.

Of course, 50 years ago, such minutiae hardly mattered. Here in the 21st century, it might just earn you a few points at a pub pop quiz. Ziggy Stardust struck a chord with those of us raised on 50s rock’n’roll, 60s psychedelia and counter-cultural hedonism. My own art student background responded enthusiastically to the concept, the art-pop/ pop-art element, the theatrical fin de siècle decadence, the faint electrical crackle of science fiction and, of course, Mick Ronson’s cosmic blues showboating.

A brilliant creation by one of pop music’s trickiest artificers, Ziggy brought theatre into pop in a manner that was seductive and challenging, yet sweetly unthreatening. For all the implied overtones of Nietzsche, Wilde and Gide in Bowie’s previous two albums, there was just as much Elvis in Ziggy as Genet.

Check out the hip shaking, the studied flick of head and hair, the orgasmic pout and the knowing grin. Hendrix or the Stones may have sent your parents scurrying for the smelling salts but the Spiders suggested drag nights at the local working men’s club, wartime Berlin cabaret and English pantomime.

My first wife barely blinked when, in the very earliest incarnation of Be Bop Deluxe, while still holding down a ‘respectable’ day job, I marched out of the door carrying my guitar case in one hand and her makeup bag in the other. I had no serious intention of launching a career on the back of it – ‘glam’ seemed little more than a giggle, an attempt to wham-bam-bamboozle the local macho boys and attract some pretty girls. But it worked in ways I could never have imagined. Bizarrely, I’m still struggling to shake off the blessing/curse of Axe Victim after all these years. (Hmm… perhaps that means I’m Ziggy.)

The album transformed Bowie’s fortunes almost overnight. Ziggy was everywhere, on the front cover of Rolling Stone and dozens of other pop culture rag-a-zines. Ziggy’s artfully orchestrated glamour and resultant commercial success opened the door to all sorts of ch-ch-changes, not only for fans but for Bowie’s career too. Popular appeal creates a fortune and fame magnet, but it attracts darkness as well as light. Did Ziggy, unbidden, become more powerful than his creator? Does Ziggy’s 40-year-old ghost still rattle the doors of Bowie’s corporate tower? The answer to that is, I think, ‘probably’.

Now, it seems almost superfluous to analyse the music. Even if you haven’t heard the album for 50 years, its echoes linger: the sign of an indisputable pop classic. What surprises me, after not hearing the album for years, is just how nasal and light Bowie’s voice sounds compared to his later beautifully rich croon, but then that’s youth for you. Time has forged from his voice a far more subtle and dramatic instrument.

Here, however, it exhibits a charmingly gauche exuberance, with the same occasional faint echoes of Anthony Newley and Mick Jagger that were evident in earlier recordings. It’s peppy and preppy, part proto-punk, part Eel Pie Island post-mod English blues.

Despite the album’s almost dry, early 70s production values, whenever Mick Ronson dives for pearls via his string arrangements and guitar dynamics, the sound noticeably opens up, broadens and deepens. Shame about the ‘pub piano’ sound though, which, via Star in particular, seems to have infiltrated both Roxy Music and Mott, though perhaps to better effect.

The main songwriting gems for me are much the same as they were back then: Starman, Ziggy Stardust, Hang On To Yourself and Suffragette City. These, above all other tracks on the album, prove the most enduring. Some of the music comes across as a frozen product of its era, even though it virtually created that era to begin with. Other aspects transcend the period brilliantly and shine way beyond it. Like so much of David Bowie’s work, it thrives on its glorious contradictions.

The original version of this feature appeared in Classic Rock 172, in June 2012.