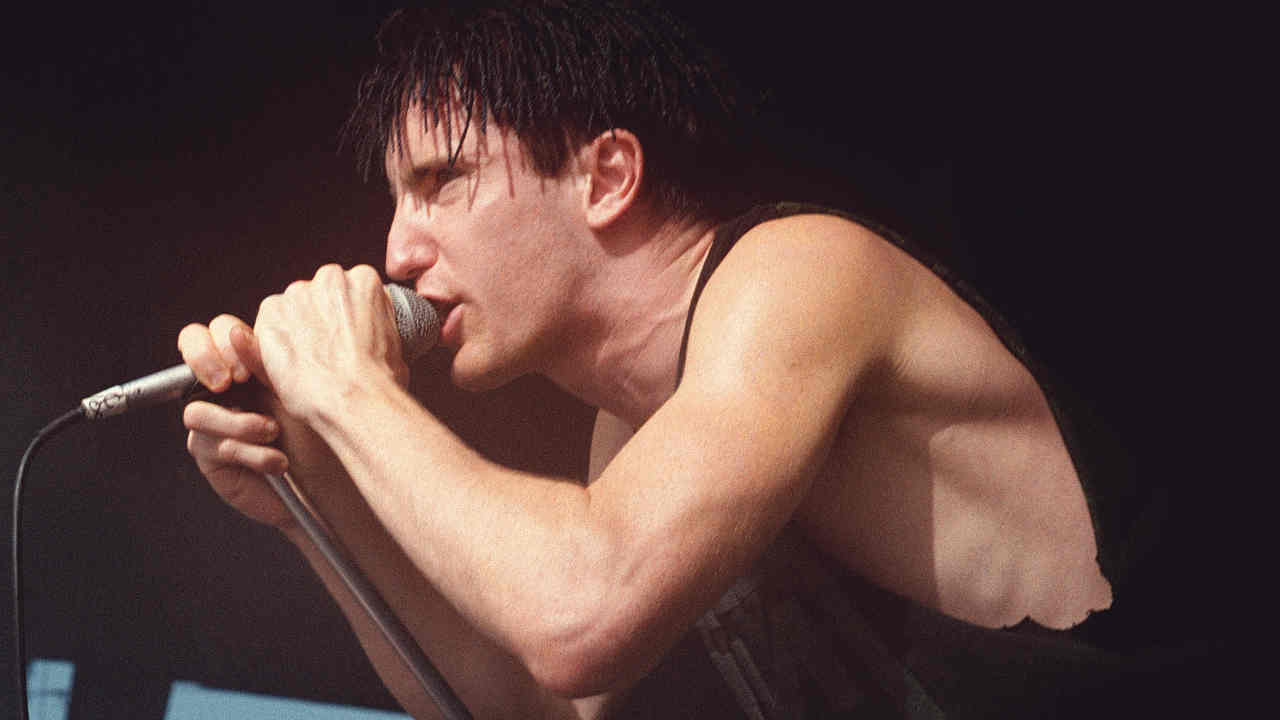

The year is 1992 and Trent Reznor is refusing to put out new music. His band Nine Inch Nails is under contract with TVT Records, who are pushing for a follow up to his massively successful 1989 debut album, Pretty Hate Machine. The label wants “commercial, easily digestible” synthpop. Reznor wants a darker, more industrial metal sound. The result is deadlock.

Reznor has spent much of his career rebelling against what he calls the “greedy record industry”. When Universal reissued Pretty Hate Machine in 2011, he urged fans not to waste their money on “record label bullshit”. In 2009, he told fans where to find illegally filmed HD footage from NIN’s Lights In The Sky tour. Prior to the release of Year Zero, he used gig venues to hide USB sticks containing leaks of unrelease, unprotected album tracks. He even took his former manager and Nothing Records co-founder to court, eventually winning back assets he’d lost through an unconscionable contract agreement. But even amid a career rich in rebellion, 1992’s Broken stands out as the crown jewel of mutiny.

When he wrote it, Reznor believed his music career was dead in the water. He’d been offered a contract with TVT based on the merit of his demos (you can find them on demo album, Purest Feeling). The label thought they were signing a pop act, so when Reznor presented Pretty Hate Machine to TVT founder, Steve Gottlieb, he was told he’d ruined what could have been a promising music career.

Broken became an artistic expression of the frustration, depression and anger he felt at that time. Almost everything about the EP is designed as an act of insurgence, from the lyrical content to the accompanying film and the cryptic messages in the liner notes. Thirty years on, it remains Trent Reznor’s finest ‘fuck you’.

Track titles like Happiness In Slavery and Help Me I Am in Hell were barely masked expressions of Reznor’s struggle for artistic control. At the 0.28 second mark of the track Physical (You’re So), Reznor can be heard whispering a dig at Gottlieb. In fact, the inclusion of this particular cover was another slight on TVT, who had previously blocked NIN from releasing it.

The EP was kept under wraps while Reznor feuded publicly with Gottlieb. He believed TVT had hindered the promotion of Pretty Hate Machine and so he initiated a lengthy legal battle to free NIN from the label. The stalemate was eventually broken when Interscope founder, Jimmy Iovine, partnered with TVT to buy NIN’s contract.

Reznor felt ‘slave traded’ from one bad deal to a worse one. In an attempt to turn the tides in his favour and regain ground, he put on a “raving lunatic act” and negotiated the creation of his own vanity label, Nothing Records.

Satisfied he’d made the best of a bad situation, Reznor presented Broken to Iovine and it became the first release from Nothing Records by way of Interscope and TVT.

The cover artwork featured a large logo for Nothing Records — a blazing emblem of rebellion. The EP credits and press sheet were laced with acidic digs at TVT and Interscope, most notably: “The slave thinks he is released from bondage only to find a stronger set of chains.”

After interference from TVT regarding the risqué BDSM content in his Sin music video, Interscope’s promise of full creative control made Reznor intensely suspicious. He put them to the test by hiring fledging short filmmaker, Jon Reiss, to make a music video for the single Happiness In Slavery. The aim was to go as far as possible…no holds barred.

They settled on a concept based on Octave Mirabeux’s French novel, The Torture Garden. The video would feature ‘SuperMasochist’ performance artist Bob Flanagan, being voluntarily tortured and disembowelled by a machine which would eventually grind him to mincemeat.

Reiss claimed that Reznor deliberately sought out filmmakers who had not been “polluted by the process” of making commercial music videos. It was his intention to make a video that had no limits…and he succeeded.

The combination of graphic violence and full-frontal nudity made the video virtually un-airable — Interscope and MTV were both furious. “This video was basically a Fuck You to the industry,” says Reiss.

Reiss went on to direct a performance music video for another track on the EP, Gave Up, which was filmed inside the Tate house. In the start of this video, the words ‘FUCK YOU STEVE’ can clearly be seen on a computer screen within the shot — an Easter egg which many believe to be another dig at Gottlieb.

Not satisfied with the chaos caused by the Happiness In Slavery video, Reznor upped the ante. He hired Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson (Coil/Throbbing Gristle) to direct a longer film which would make Happines In Slavery “look like a Disney movie”.

In a 2014 interview, he said: “There was no label involvement or pressure from anyone, it was just he and I talking. ‘What if we built a framework around these songs, what if we took an approach where it really was scary, instead of a cop out horror movie nod to the camera. What if it felt real?’”

They weren’t playing around. The result, known as The Broken Movie, was far more real than either of them anticipated. It contained six short films acting as music videos for the Broken EP, all linked together with a found footage narrative in the style of a snuff film.

Only two of the music videos (Wish and Happines In Slavery) actually featured Reznor or the band — the rest were unsettling narratives of rape, torture, cannibalism, and murder. The footage was so shocking that Christopherson requested to send Reznor the master tape in an unmarked envelope to avoid it being traced back to him.

The film was ultimately shelved when Reznor decided that, when combined with his decision to rent the Tate house, the tape was too much. "I thought, 'Enough. I don't know that I need this kind of thing.' With the house it felt too stunty, and Peter agreed. So we shelved it."

Not wanting the work to go to waste, Reznor posted copies of the VHS to selected friends, each with its own unique dropout so he’d be able to identify the culprit in the event of a leak. His suspicions weren’t unfounded. Bootleg VHS tapes made their way into circulation and went viral, cementing the film as an underground cult classic (albeit a horrific one). Poor image quality from repeated tape duplications even left some fans wondering whether they were watching real snuff film footage.

.

The Broken Movie was far too graphic to ever see official release, but that didn’t stop Reznor from including a sizable portion of the footage in the video album Closure. It has since leaked several times, with many NIN fans believing Reznor to be the culprit in each instance.

The film is a shining example of an artist pushing back against the system which supressed the darkness he was trying to express. Distribution of the film continues to this day and is still perpetuated by Reznor, who has included a secret link to the full video on the NIN discography page

At the time of its release, Reznor referred to Broken as an ‘ugly record’ made at an ugly time in his life. But that didn’t stop it from going platinum or charting at number 7 in the US Billboard 200. The EP won Reznor two Grammy Awards for Best Heavy Metal Performance, one in 1993 for Wish and one in 1996 for Happines In Slavery. He would later joke that his epitaph would read: “Died. Said ‘Fist Fuck’. Won a Grammy”.

Although NIN would remain under contract with Interscope until 2007, the release of Broken signified a minor victory for Reznor: he had regained some of his creative control, proved his bankability, and cemented NIN’s place as an alternative music zeitgeist. Broken also marked the first tentative steps toward what many believe to be NIN’s greatest album, The Downward Spiral.

Much of the creative output from NIN is a deliberate challenge to authority, but the story behind Broken makes it stand apart. Not only is it an epic ‘fuck you’, it’s a fuck you which still resonates thirty years later.