Why the true story of Glam Metal needs to be told

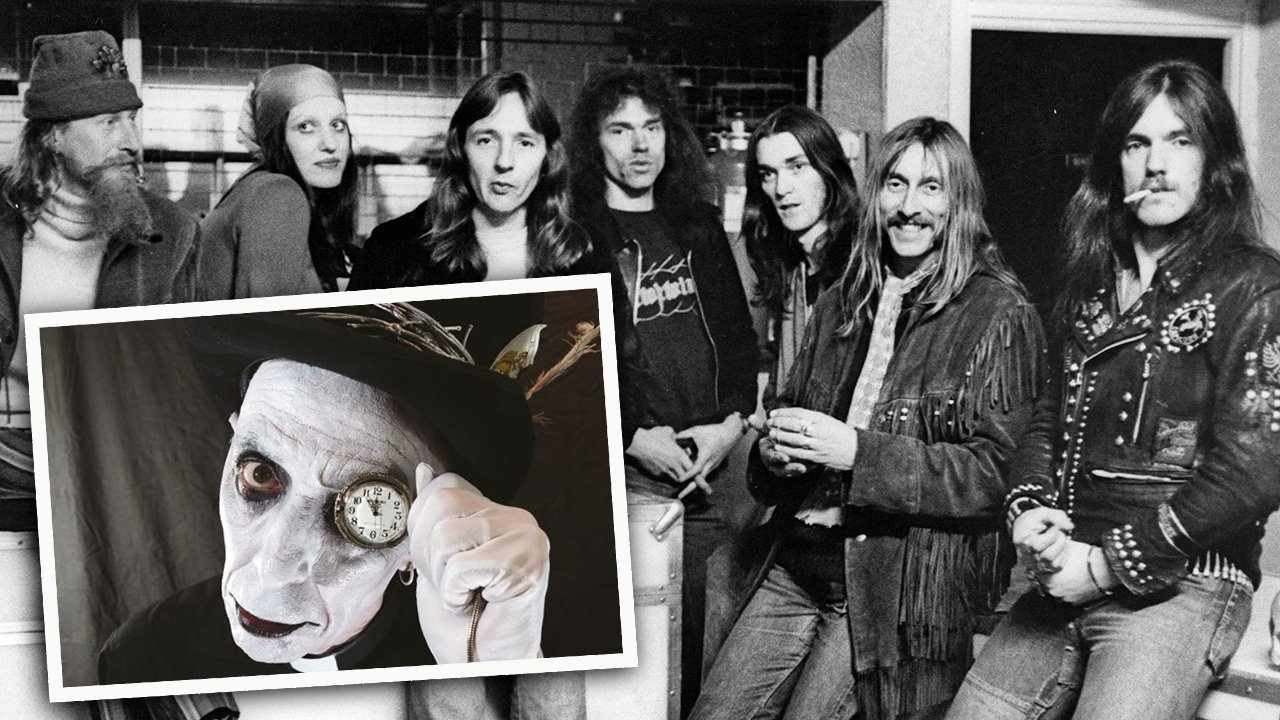

Glam Metal once bestrode the globe like an enormous, hairspray-drenched goliath, but it's almost been written out of history. We meet the man who plans to change that...

“It was what MTV was built on, and what sold out stadiums all over the world,” says Justin Quirk, author of the forthcoming book Nothing But A Good Time - The Spectacular Rise and Fall of Glam Metal, which aims to tell cultural history of the genre. “It struck me that there had to be a story in there.”

For a while, back in the 80s, Glam Metal was everywhere. For rock fans growing up in the UK, where the sound of hard rock was invariably accompanied by the stale, sickly scent of patchouli and two litre bottles of warm cider, its emergence provided an impossibly glamorous glimpse into another world altogether.

It was a world where the party never stopped, where men embraced the feminine and made themselves more attractive to females in the process, where you could go to Hull, or Hatfield, or Huddersfield, and find a taste of Hollywood if you knew where to look.

Conventional wisdom states that a cold wind blew in from the Pacific North West and the party stopped, and everyone knows that story. But the years that preceded grunge? Now there’s a tale that deserves to be properly told.

“It struck me as odd that this kind of music has been sort of written out of history, and seems to be pretty much the only genre which is considered completely beyond the pale in terms of serious critical reassessment,” says Quirk. “The emergence of grunge obviously hit glam metal very hard, but part of the response seems to have been a kind of collective embarrassment, and a general denial that anybody was ever into this stuff. And I knew from my own memory that these bands were huge at the time - it wasn’t some niche concern that was limited to one place.”

Quirk, who has written for The Guardian, Kerrang!, Esquire, The Times, Sunday Times and The Independent, is currently running a crowd-funding campaign in order to finish the book. Contributors will get their names featured in the finished publication, while those prepared to splash out a little more money can claim rewards that include Quirk DJing at an event of their choosing.

Why does glam metal deserve a book?

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

It struck me as odd that this kind of music has been sort of written out of history, and seems to be pretty much the only genre which is considered completely beyond the pale in terms of serious critical reassessment.

When I started researching it, I realised that what I didn’t really want to do was an exhaustive user’s guide to glam metal - partly because it wouldn’t be that interesting, but also because those things always feel like you’re on a hiding to nothing, and will always miss out something which someone considers important.

I was more interested in stepping back a bit and looking at why it happened where and when it did - and the more I looked into it, the more it felt like a real product of its environment. This decade when America was rebuilding itself after a very fractious seventies and early eighties, and seemed to be regaining its confidence culturally. Action films, wrestling, huge stadium shows, yuppie culture, MTV, America winning the cold war, huge works of art etc - everything seemed to be getting bigger and more inflated and excessive, and it seemed like glam metal was the musical wing of all that. But over the course of the decade, it gradually soured into something a lot darker.

I think Appetite For Destruction is probably the crucial turning point in all that - on the one hand, as an album that’s got all the key elements of 80s excess (drugs, women, partying, LA etc), but they’re all portrayed in a really grim, seedy light. The comparison for me is with that strand of sixties hippy culture, where things start off as fun and liberating, but end up with Manson and Altamont. Those scenes where the wheels come off really badly are always grimly fascinating.

Who should buy it?

Not just diehard glam metal fans - I want to write something which is of a wider interest to anyone who thinks about why music turns out the way it does, and how it can’t really be separated from the culture around it. America was in a fascinating place at that time, and I think we’re still dealing with the repercussions of it to some extent. It’s a cultural history more than just a narrow musical one, although you might get more out of it if you accept that Hysteria is one of the greatest albums ever made as a starting principle.

What would you say to fans who look back with a degree of embarrassment about their glam metal past?

That’s a natural part of growing up, but you shouldn’t be too hard on yourselves. While there was something ostensibly ludicrous about walking around a suburban town in south east England in cowboy boots and a top hat, it’s no more or less ridiculous than most phases people go through. And as they say in The Wrestler - ‘Was there something wrong with just wanting to have a good time?’

- The 10 Essential Glam Metal Albums

- Bon Jovi: Songwriters, Strippers and Suds – the Story of Slippery When Wet

- Our TeamRock+ offer just got bigger. And louder.

- 10 Hair Metal bands who should have been huge

You’re a DJ. What’s the one glam metal track guaranteed to fill the floor?

It’s a hugely obvious choice, but You Give Love A Bad Name is an absolutely perfect, machine-tooled pop song which will be getting played to big groups of rowdy drunk people until the balloon goes up. That and Living On A Prayer are basically the same tune just slightly reworked, but they’re completely irresistible - the production is great, the backing vocals are just right for yelling along to, and they absolutely hit the ground running.

They actually have an enormous halo effect on the rest of Slippery When Wet which is really not as great an album as people remember - most of side two is pretty forgettable, but those singles just lift the whole thing.

Is glam metal ripe for a non-ironic return? After all, Ratt and others feature fairly prominently on the soundtrack to the latest series of Stranger Things.

I can completely see this happening. I was thinking about it last summer when Barry Gibb played at Glastonbury - he looked at first nervous, and then cautiously relieved, then finally weirdly touched that he’d been welcomed like that by the crowd and they acknowledged him as a genius. 10-15 years ago, disco was essentially treated as a novelty, only played at fancy dress nights, written off as this frothy, lightweight thing and people like Nile Rodgers were these peripheral figures. But people went back, and reassessed what they did and realised how important it was culturally and musically, and now treat them with absolute reverence.

I think you’re getting the first stirrings of that - Mariah Carey and Taylor Swift both covering Def Leppard songs, those recent WASP shows in London seemed to be the biggest shows they’d played in a long time etc – but I would genuinely be unsurprised if that slot at Glastonbury in a few years time has someone like that playing.

Online Editor at Louder/Classic Rock magazine since 2014. 39 years in music industry, online for 26. Also bylines for: Metal Hammer, Prog Magazine, The Word Magazine, The Guardian, The New Statesman, Saga, Music365. Former Head of Music at Xfm Radio, A&R at Fiction Records, early blogger, ex-roadie, published author. Once appeared in a Cure video dressed as a cowboy, and thinks any situation can be improved by the introduction of cats. Favourite Serbian trumpeter: Dejan Petrović.