When you settle down to speak with former Dr Feelgood guitarist Wilko Johnson about the constituent parts of his recently curated Wilko Johnson Presents The First Time I Met The Blues: The Chess Masters collection, you must first recalibrate your definition of the word ‘enthusiastic’. To bear witness to Wilko considering the recorded legacy of Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Howlin’ Wolf and Chuck Berry is an inspiring spectacle indeed.

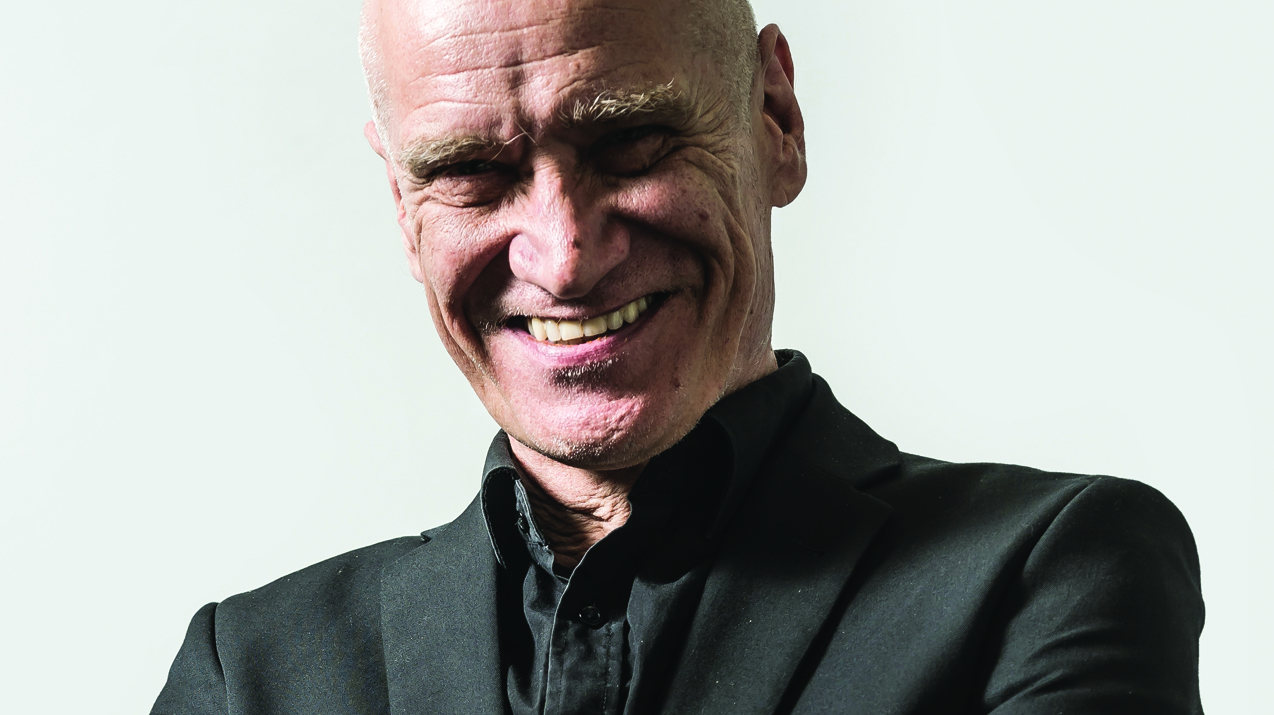

Wilko possesses what one might call a quite extraordinarily expressive face at the best of times, but when called upon to describe Hubert Sumlin’s Smokestack Lightning licks, Otis Rush’s train whistle sibilance or Little Walter’s wordless scowl it’s quite a sight to survey.

The eyes bulge, the jaw slackens, pregnant pauses hang heavy in the air between heartfelt and awestruck ‘Wow!’s. Riffs are sung as they’re recalled, beats stomped emphatically. The head jerks spasmodically from left to right in a gesture so familiar from the stage. Wilko’s restless animation is no mere stage act though, this is the actual, skull-spinning rate at which he chooses to live his life. And, for a man whose last chess opponent was The Grim Reaper himself, he’s the most entirely alive person you’re ever likely to meet.

So what is the secret of Chess Records’ immense success and continuing influence? “I’ve absolutely no idea,” admits our pallid expert with a delighted, eyebrows-aloft beam, “But I was asked to compile this selection, and what an easy job! With Chess you just dip your hand in the bucket and come up with gold.”

Wilko first encountered the delights of Chess R&B in 1964: “I really started finding out about rhythm’n’blues because of The Rolling Stones. I was mad for the Stones and wanted to know where they were deriving this music from. Their first album was nearly all covers and a great many of those covers were by artists associated with Chess, Muddy Waters and people like that. So then you’d start finding and checking out these artists for yourself, and their music was a revelation. It was so powerful you didn’t know how they were doing it. I remember back then that if you saw a disc with a Chess label, it made you excited just to look at it, because you knew there was something great on that disc.”

Living on the outer edge of the Thames Delta, on Canvey Island, and saving every spare penny for a Telecaster of his own made record-buying almost impossible: “But you could borrow records from school friends.” There were, however, a pair of truly essential albums that effectively changed the direction of Wilko’s young life: “Two great compilations from the Chess label were released on the Pye International R&B label – which had a very distinctive yellow and orange label that used to give me the shivers as well – The Blues Volume One and The Blues Volume Two. A whole lot of my early R&B education came from those records.”

Here’s hoping these timelessly visceral recordings, many of which have been re-compiled by Wilko himself on The First Time I Met The Blues, will inspire a whole new generation.

Muddy Waters

I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man (1954)

“The power and expressiveness of Muddy Waters’ voice is just miraculous, so direct, and the song’s marvellous. Willie Dixon wrote so many great songs. I first heard Muddy when the first Rolling Stones album came out. I also remember there was this fantastic television programme, a live British blues show filmed on a railway station in the rain [Granada TV’s Blues And Gospel Train of 1964, which also featured Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Otis Spann, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee]. Muddy made his entrance walking along the railroad track. He was playing a Fender Telecaster, which excited me because my hero, Mick Green [of Johnny Kidd’s Pirates], played one and I wanted one. Muddy played it with a slide, and when he hit this first note… Oh man, it just sounded so good. All these blues guys were just so cool.”

Little Walter

My Babe (1955)

“Little Walter was a bit of a dark character. Came to a sticky end. I saw him at Newcastle City Hall in 1967. He came out on stage, did My Babe and Juke, and didn’t say a word. He just scowled at the audience, which was great. Hear one note from Walter and you know who it is, he’s just the sound of the blues. He’d been in Muddy Waters’ band and his harmonica playing was a huge influence on Lee [Brilleaux, Dr Feelgood frontman]. Lew Lewis loved him. When I first heard these records, I didn’t have a clue who was doing what or how they were doing it, and now I’ve been at it for 50 years, I’ve got half a clue. This wasn’t pop music, this was dark, heavy stuff that made you feel like a little white schoolboy. Little Walter really was spooky, all that ‘Get me a mojo hand’ stuff, so exciting and so strange. The blues wasn’t just a catchy tune and a chorus at all.”

John Lee Hooker

Sugar Mama (1952)

“I probably listen to more John Lee Hooker at home than anything else. I first heard Sugar Mama on The Blues Volume One, it’s just John Lee Hooker and his guitar. Oh man, that’s a mysterious one. He’s not playing a regular riff, he don’t give a damn about no 12-bar, he’s going to change the chords where he feels like it. It’s not flashy guitar, but it’s powerful. His voice is so vibrant and heavy, it sounds so free and natural. It’s hard to put into words the power that these people exuded. Obviously, it came from black culture in America, it was something they were born into, but you could live for a hundred years and never play the boogie like John Lee Hooker.

“There’s menace lurking in all this music, a potential for violence, an unspoken threat. ‘I’m drinking TNT and smoking dynamite, I hope some screwball starts a fight’. One of the things we used to love in Dr Feelgood was putting on the violence. We’d stare people down and my guitar was my machine gun. It was all just absolute pure enjoyment, everybody loves playing cops and robbers. When you’re a kid playing cops and robbers your fingers really are a gun, they really are, and it’s the same with my guitar. It really is a machine gun: ‘bang, bang, bang’, and you’re feeling that violence. Lee would be standing there – and to me Lee was always the leader of Dr Feelgood, look at any pictures of Dr Feelgood and I’m looking at Lee, taking my cue from him – and he’d go, ‘It’s time for the guitar solo… boom’, and I’d go ‘whoom’, do my thing and ‘whoom’, I’m back by his side again. It was just like a gang. He was the leader and I was the guy that… killed people.”

Bo Diddley

Gunslinger (1960)

“I became aware of Bo Diddley before discovering the Stones because Buddy Holly had a posthumous hit with the song Bo Diddley, and I’d heard Bo’s version of that. I got given Bo Diddley’s 16 Greatest Hits – again on the Pye International label – for my 17th birthday. Every track was just so exciting: real jungle music, just… Wow. The drums and guitar are just so off the wall. He had this vibrato effect on the guitar and was known as a bit of an experimental guitarist, but he was also a poet: ‘Bo Diddley didn’t stand no mess. He wore a gun on his hip and a rose on his chest.’ Oh, what! He was like a forerunner of rap music, that song Say Man is even delivered like a rap. He played Dingwalls one time and me and my band backed him and, well… It was good.”

Sonny Boy Williamson

Don’t Start Me Talkin’ (1955)

“Although there were two Sonny Boy Williamsons, it’s the second Sonny Boy that we all know and are most familiar with. He had this kind of cool voice. It wasn’t intense like Muddy Waters, it was more laid-back. He was a great harmonica player too. I remember he used to do this thing where he played it with his nose. He looked like a jazzer, he had this hat… I don’t know much about jazz, but he looked a bit be-bop; a bit cool jazz. He used to radiate a very friendly, groovy feeling in his music. And this is a great song, I often use that expression myself, someone will ask me about somebody or something and I still say, ‘Don’t start me talkin’ or I’ll tell everything I know’. It’s such a great phrase, and while he has that whimsical jazz delivery, he’s singing with absolute authority. I never saw him, even though he was in England a lot. In those days I was a schoolboy on Canvey Island, going to a gig in Southend involved big expenditure for me. London? You might has well have asked me to go to the moon. I never went to The Marquee until I played there with Dr Feelgood.”

Howlin’ Wolf

Smokestack Lightning (1956)

“Oh, The Wolf, what can you say? His voice is like a force of nature, extraordinary. When he’s singing he sounds like the microphone is going to explode and the speakers are going to blow, because his voice is just so powerful. You have to hear it. It’s hard to describe. He was such a big man, and he sounded like it. When he held a Fender Stratocaster it looked like a little ukulele. His band featured Hubert Sumlin of course, a man that was responsible for some of the most powerful and expressive guitar playing you can hear anywhere. Smokestack Lightning? Now there is some spooky stuff. What an evocative record. That riff, and The Wolf’s singing, ‘woo-ooo’ and all that. You get this picture of a shack by a railroad track, lightning striking and this guy literally howling for his baby. The phenomenal voice of the Howlin’ Wolf, the sound of Hubert Sumlin, the songs of Willie Dixon. Even after all these years, there’s nothing to touch it… Nothing.

“And there never can be, because all of these people came from a time and a place, all of these extraordinary musicians gathered around the Chess label. Oh, to have been in that room while they were making that music.”

Otis Rush

So Many Roads, So Many Trains (1960)

“Again, this song was on that Pye International The Blues Volume One album, and it’s just got the most amazing guitar sound on it. When me and my brother first heard it we were trying to work out what it was: ‘Is it a saxophone?’ [Sings] ‘doodle-doodle-doo’… Wow! And his voice was so soulful. He was one of those people that had that whistle on his sibilance. So he’s singing ‘So many roads, so many trains’ with a whistle on every single ‘s’. ‘I was standing at the window, When I heard that whistle blow’ [whistles Wilko, laughing]. Me and my band played with Otis at The Town And Country Club a few years ago.

“When I discovered authentic blues, I never went off The Rolling Stones though. I was led into this by The Rolling Stones, they were just so phenomenally exciting, and as a schoolboy they just seemed so incredibly anarchic. I loved the Stones. Thought they were great, I’ve never lost my enthusiasm for The Rolling Stones, they had their own take on the blues and went on to do stuff like Brown Sugar which is absolutely great, and developed from the blues.”

Buddy Guy

First Time I Met The Blues (1960)

“Wow! Another one. What a voice. What a guitar. I remember him appearing on Ready Steady Go!, and I was already into him. First Time I Met The Blues is such an amazing song. Another spooky one. What’s he talking about, man? The blues is chasing him. He’s going, ‘Blues, blues don’t murder me’, and he’s running through the woods, tremolo guitar chords are hitting and saxophones droning and it sounds like a bloody nightmare, and you can hear this guy screaming, ‘The blues are after me’.

“Back then Buddy Guy was a technically brilliant guitar player. In later times he did achieve some more success, but I think he went too much in the direction of Hendrix, and don’t go there, cos nobody can get there. Though many have tried.

“In about 1967, I used to play this regular Thursday gig at the London Hotel in Southend, and sometimes nobody would turn up apart from [British musician] Mickey Jupp, his brilliant guitarist Mo Witham and Robin Trower, and I can remember sitting at the back of the hall in the break and they were playing records. There was this girl I was looking at, and they were playing Rex Garvin & The Mighty Cravers’ Sock It To ‘Em JB. [Sings] ‘ba-dup, buppa-duppa-dup’, and every time it went ‘buppa-duppa-dup’ she’d wiggle her backside and… What! Then they played Jimi Hendrix’s Stone Free and Robin Trower went ‘That’s what I wanna do’. And, well, that’s what he did.”

Tommy Tucker

Hi-Heel Sneakers (1964)

“Tommy Tucker is a keyboard player and Hi-Heel Sneakers was a massive hit record, very groovy, very danceable, but the guitar playing on it is absolutely great. There’s this organ bit, but the guitar part is just sweet and beautiful. On the B-side of Long Tall Shorty there’s a track called Mo’ Shorty, which is the backing track of Long Tall Shorty with lead guitar over the top playing the tune, and it sounds brilliant. He’s obviously using a Stratocaster because it’s got that sweet Stratocaster sound, and he’s shaking on the tremolo arm. I don’t know who the guitar player is [it’s Weldon Young, by all accounts], but Tommy Tucker made these two absolutely superb records, Long Tall Shorty and Hi-Heel Sneakers, which had I Don’t Want ‘Cha on the B-side, with yet another great guitar part. Everyone in the world knows Hi-Heel Sneakers, but I’m sure very few people could tell you who’s doing it.

“Very few of these artists made any money out of any of these records, they were all being ridiculously exploited. What we’ve come to know now as a fair return for doing it just wasn’t there then. It’s a situation that led to John Lee Hooker moonlighting as John Lee Booker, recording for all sorts of people because he was only paid a few dollars per track. Of all the money that Hi-Heel Sneakers made, how much got back to Tommy Tucker? Probably not a lot. I’ve spent a fair amount of my career without a record deal and every now and then I’ve made a record for an independent label. Even as you’re doing it, you know you’re never going to see any money… Bastards [laughs].

“But I’ve had a pukka deal too, I still get royalties and statements back from the stuff that I did with Dr Feelgood. I’ve probably made a million by comparison with what Muddy Waters got. Which can’t be right. They should have paid Muddy much more, not me less [laughs].”

Chuck Berry

No Particular Place To Go (1964)

“What can you say about his achievements? Chuck Berry is absolutely one of the greatest songwriters of the 20th century, and has said absolutely everything that there is to say about American cars. If you go and buy a greatest hits selection of Chuck Berry, it’s just one classic after another. I’ll always remember the first time I heard Memphis, Tennessee, which is another strange one. It’s got such a plaintive sound and the lyric is so brilliant, and it pays off in the last line when you realise he’s singing about his little daughter. Everything that comes before takes on a different significance when you realise that. What a brilliant lyric. And, of course, the opening riff to Johnny B Goode, I mean everyone’s got to know that, ain’t they? But I think the guitar solo on No Particular Place To Go is one of the greatest pieces of guitar playing on record. And its opening chord? Someone taught it to me at school and one of my favourite tricks is to walk up to somebody with my fingers on that chord, go ‘What’s that?’ They go, ‘I don’t know’ and you go ‘duddle-a, duddle-a, duddle-a-duh’, and they all know it, because it’s so distinctive. Yeah, Chuck Berry, what a showman. All those songs, it’s mind-boggling, there are literally hundreds, and so much of rock’n’roll was defined by what he did.

“I’ve seen him play a few times, but the first time was at Southend Odeon. I knew all his records, but didn’t know about the duck walk. It was mental. During the second or third number I jumped out of my seat and ran to the front, then the whole audience got up, and as I ran towards the stage he looked at me. I can remember boasting about it later. It was great. Anyway, as I say, stick on a Chuck Berry greatest hits album and you realise that he’s created a songbook that’s entered the consciousness of the human race, and it is just so glorious and happy and… Oh wow, how much joy has that bloke brought to the world?”

Wilko Johnson Presents The First Time I Met The Blues: The Chess Masters is out now on Spectrum.