As the 70s progressed, the exponents of progressive rock expanded their artistic visions exponentially. Compositions grew beyond 12”-vinyl confines and arrangements embraced lavish complexity and epic scope. Yet while their peers stretched out toward outer space, Wire focused their experimentation on inner space. Just as the newly stadium-dwelling prog colossi were endeavouring to dazzle vast crowds with grand musical gestures, Wire were down in the dance halls looking to inject fresh vitality into a stale old ceremony.

At the close of ’76, and with punk’s brightest hopes already settling into their role as the new guard of Chuck Berry-rooted rock‘n’roll orthodoxy, Wire were one of a few emerging bands truly worthy of the much over-used epithet ‘new wave’, let alone the ultimate accolade of ‘progressive’. And so, as their peers and forebears set about reconstructing the time-honoured building blocks of rock into ever more baroque sonic structures, Wire simply set to work designing better bricks.

Over three frenetic years and three landmark albums Wire reinvented what rock could be, from the ground up. With initially limited technique the original quartet of Colin Newman (guitar, vocals), Graham Lewis (bass, vocals), Bruce Gilbert (guitar) and Robert Gotobed (drums), employing a modus operandi acquired at art school, set about identifying exactly what it was that they were good at.

“We decided we were good at stopping and starting,” remembers Graham Lewis. “And we got an incredible thrill from it. The first thing we discovered that Wire had between the four of us was a sense of where the gap was. I suppose the break in 12 X U [on Pink Flag] is the best example of that. The thrill when everybody came back in at the same time. It wasn’t counted, it was intuitive. Very precise… We liked precise. And fast and slow. These were our compositional tools and we made the most of them.”

It sounds preposterously, childishly simple, but that, in a nutshell, is the magic of Wire. Nothing is ever overly complex, nothing is ever overly anything, but elements are placed together with such complementary precision in compositions of such fat-free concision and melodic perfection that Wire’s best moments rank alongside Pink Floyd’s best moments. And while Floyd will sometimes take 20-odd minutes of atmospherics and ambience to get you to where you need to be, Wire can casually coax your finest hairs aloft in a sub-two-minute ode to a silverfish.

And then there’s their characteristic rhythms; their jerky syncopations. It’s very hard to be directly influenced by Wire without stumbling into unintentional plagiarism, anyone who hears Three Girl Rhumba or Practice Makes Perfect – just like Blur and Elastica before them – is going to want to do something like it, because, well, it’s brilliant. But you can’t do something like it, you can only copy it, because it’s so well constructed, so utterly devoid of anything superfluous, that it’s perfect.

How then does one attain such perfection? Well, first of all, you attend a 1970s art school where, according to Graham Lewis: “What they taught was thinking, which gave you the nerve, the confidence and flexibility to pursue something outside the status quo and, inevitably, the peers you meet at such establishments encourage you in that constant pursuit of the new.”

“Art school’s ultimately about ideas,” agrees Colin Newman. “What I learned in art school was that it’s okay to call yourself an artist, it doesn’t have to have an ‘f’ in front of it. I was really pretentious when I was in my early twenties, but I felt seriously that I was doing something new, and Wire was a good context to be doing it in, because we all had that same conviction, they all liked newness.”

In short, in order to progress, you’ve got to be progressive. Specifically though, how do you become Wire? How do you stumble upon an entirely inimitable style? The undeniable, matter-of-fact lope of Lowdown; the crooked, Britpop-exemplifying beat of Three Girl Rhumba or Practice Makes Perfect?

“Lowdown is a manifesto,” reveals Lewis. “I didn’t realise until about 10 years later because I didn’t turn the paper over. There were more verses written on the other side of the bit of paper, but I never turned it over.” Best laid plans, eh…

“Lowdown is funk slowed down until it loses its funk,” says Newman. “It’s a classic funk riff slowed down until it becomes something else. It was one of the first Wire songs, but its concept undermines the whole notion of Wire being a punk band, it doesn’t conform to any of the punk aesthetic.”

“In that mid-70s period we were listening to Sly Stone,” Lewis nods. “Sly was doing more radical records than the white boys were doing.”

“Practice Makes Perfect, that’s the perfect Wire song,” Newman insists, “I walked into the rehearsal room, started playing and singing it, and by the time I’d gone through it once – the arrangement was already there – they’d already worked out their parts. You just give them the notes, and they find their parts. With the staccato Practice Makes Perfect riff it would have been so obvious for any drummer to have just mirrored that on the toms. What did Rob [Gotobed] do? Reggae, the side-stick, syncopated feel, that’s how he heard it, so that again became something else.”

“Can, Kraftwerk, Neu!, The Grateful Dead – it’s all dance music,” adds Lewis. “But badly done by white boys.” Wire were signed to EMI’s original progressive rock imprint Harvest by A&R man Mike Thorne who, between 1977 and ’79, produced the band’s opening trilogy of albums.

“Mike recognised that we were serious about what we were doing and that it was fully formed,” offers Lewis. “He said he couldn’t understand how we’d done it, but that we seemed to understand what we were doing.”

If we were likened to King Crimson in 1969 we would be very, very happy to be prog.

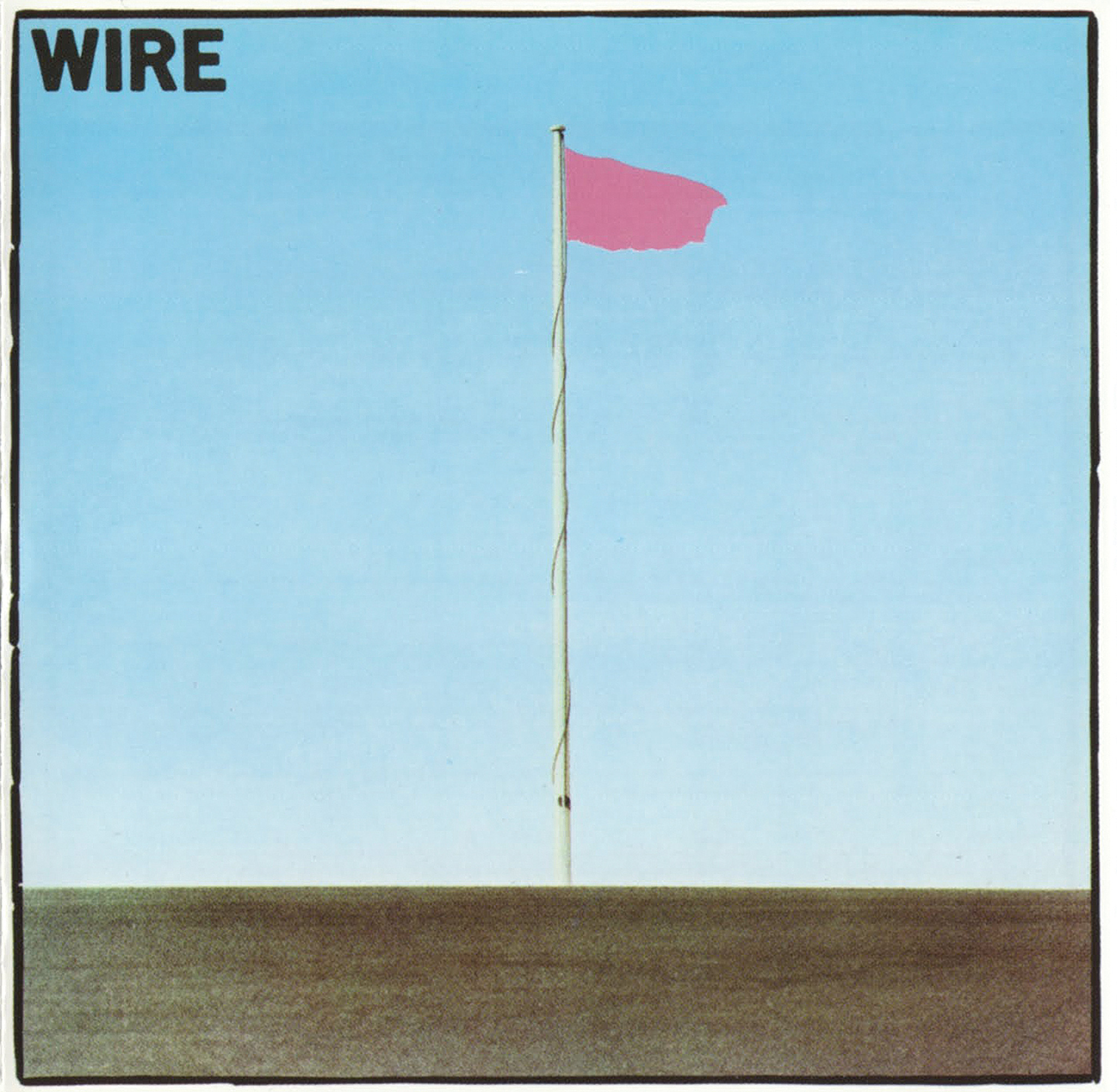

It was Thorne who was responsible for the band’s 1977 Pink Flag debut capturing such an undiluted document of Wire Mk 1 for posterity. The four were writing constantly, developing in leaps and bounds, but Thorne saved the band’s more considered and sophisticated compositions for album number two.

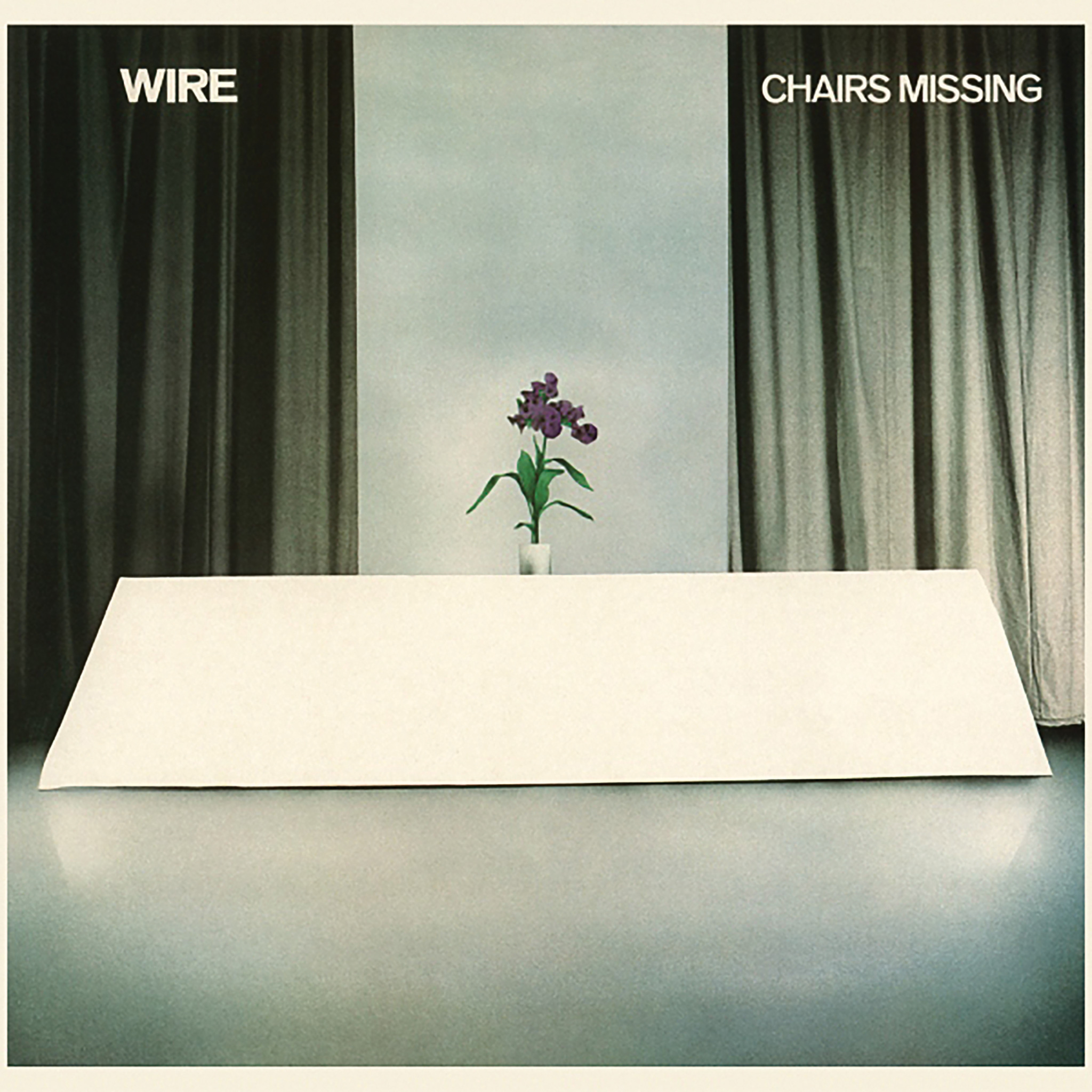

By the time ’78’s Chairs Missing arrived, Wire had been joined on the post-punk frontline by similarly progressive bands XTC and Magazine. In academic retrospect it looks an awful lot like a loosely connected movement, a new wave of post-punk prog even. Graham Lewis would beg to differ: “I think it’s a load of bollocks.”

That said, Colin Newman, though reticent to be pigeonholed into a sub-genre, isn’t averse to Wire being accorded prog status: “If we were likened to King Crimson in 1969 we would be very, very happy to be prog.” Lewis, meanwhile, is suddenly very keen to discuss Garden and Eccentric Man from The Groundhogs’ Thank Christ For The Bomb album.

Upon delivering third album 154 (its September 1979 release coincided with the band’s 154th gigs) arguably their most traditionally progressive recorded statement to date, Wire left Harvest and, ostensibly, set about courting eligible labels. But, as Newman admits: “Wire was in the process of ceasing to exist at that point. We were poorly managed, didn’t make any money, the group sort of dissipated.”

Of course, Wire reconnected in 1987, again in 2003 and having continued to move forward in dogged pursuit of invariably engaging incarnations of ‘the new’, remain as relevant and progressive as ever.

On the eve of the release of their stunning 14th studio set, Colin Newman asserts: “Wire aren’t a classic rock band. It’s not that we’re not proud of the records we made in the 70s, it’s just that we feel we’ve something new to offer, and new things are what we’ve always been about.”

Wire’s self-titled album is out now on Pink Flag.