As they prepared to take the stage to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the original Woodstock, Nine Inch Nails looked out from the covered backstage area at the sheets of rain pouring from the sky. The 200,000 fans waited on the mud-slick field, poised for the moshpit to erupt.

Nine Inch Nails had played festivals before, but nothing on this level, and the guys – frontman Trent Reznor, guitarists Danny Lohner and Robin Finck, keyboardist James Woolley and drummer Chris Vrenna – were anxious and fidgety before showtime. The weather was irrelevant. It was time to sink or swim.

To ease the tension, James scooped up some mud and flicked it at one of his bandmates, who responded with a playful, “Fuck you,” and flung a larger handful back at the keyboardist.

“It was like the beginning of a food fight,” Chris recalls. “One thing led to another, and the next thing we knew, everyone was covered from head to toe and we were all laughing for the first time of the day.”

Mud was even more omnipresent for Woodstock ’94 than it had been in 1969. At the back of the fairgrounds, fans danced in dirty-brown, knee-deep puddles. In the moshpits, they slid into one another as if they were fighting on ice skates.

And other bands, especially Green Day, turned a potential disaster into a free-for-all party. When the crowd started throwing clumps of dirt at them, they embraced the chaos, flinging it back and triggering a giddy, chaotic mud fight.

By the end, frontman Billie Joe Armstrong had dropped his pants and a security guard had accidentally clocked bassist Mike Dirnt in the mouth, knocking out some of his front teeth.

The show did for Green Day what the mud costumes did for NIN; footage of the show was repeatedly splashed across MTV and three months later Green Day’s second album, Dookie, hit No.4 on the charts.

If there was a theme song for the festival, it’d be Primus’s My Name is Mud. But rather than trash the venue – as some fans did at Woodstock ’99 – or get mad and leave, the majority of crowd members revelled in it.

Motivated by recreational pharmaceuticals, primal lust or a combination of both, they spent as much time frolicking in the mud at the back of the festival grounds as they did in the audience.

“There was shit going on back there that had nothing to do with what was going on by the stage,” recalls Blind Melon guitarist Rogers Stevens. “It was like Lord Of The Flies. You could vaguely hear music and there were giant mud puddles with naked people writhing around. Some of them were dancing, some were, uhh, doing other things.”

The line-up for Woodstock ’94 included alumni from Woodstock ’69 (Santana, Joe Cocker, Country Joe McDonald) and old-schoolers who didn’t play the original festival (Jimmy Cliff, Allman Brothers, Bob Dylan).

But most of the highlights were newer, heavier and more contemporary bands. In addition to Nine Inch Nails and Green Day, the event featured Metallica, Aerosmith, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Jackyl, Porno For Pyros, the Rollins Band, Candlebox, Collective Soul, King’s X and Primus.

Alice In Chains were originally booked but had to pull out since vocalist Layne Staley was in drug rehab. As a consolation, guitarist Jerry Cantrell took the stage at the end of Primus’s set to join a jam redolent of Led Zeppelin’s Dazed And Confused.

“What was going on [for the original Woodstock] was the best contemporary bands for 1969,” Metallica’s Lars Ulrich told MTV before the group’s monster set.

“Now, we have the best contemporary bands for 1994. Music has evolved and society has evolved. Anyone expecting this to be a reprise of what went on 25 years ago should have their head examined.”

In 1993, the Woodstock team rented out the 840-acre Winston Farm in Saugerties, New York. It was the location where Woodstock 1969 was scheduled to take place, before the owners got cold feet, forcing promoters to move it southwest to Max Yasgur’s Dairy Farm.

The line-up was announced on June 14, just two months before the concert. Some celebrated the news. Some didn’t. Purists argued that the new acts – especially the heavier ones – tainted the legacy of the original Woodstock.

Others complained that the $135 ticket price and corporate sponsorship (including abundant Woodstock merch and a pay-per-view simulcast) killed the organic, grass roots vibe of the 1969 event.

Communities around Saugerties worried that local highways and roads weren’t large enough to accommodate street traffic from 200,000 expected attendees.

“The mainstream press was negative from the start,” recalls John Scher, then president of Polygram Diversified Entertainment, which co-promoted the event with Woodstock Ventures. “For months they said, ‘There’s gonna be riots and crime.’ That didn’t seem to stop anybody from buying tickets, but it made our lives pretty hellish.”

Originally, promoters planned a two-day weekend festival across August 13-14, but added Friday to the schedule when they realised there was a surplus of groups that wanted to play, and that they could entertain campers who arrived early.

Jackyl were the first metal band to play on Friday. Vocalist Jesse James Dupree took the stage in an Uncle Sam hat and a mirror shard jacket that weighed 40 pounds. He started by pouring whisky over the crowd. Then someone tossed a joint onstage and he sparked up, unconcerned about the area’s strict drug laws.

“They were being a little heavy-handed about drugs and alcohol, but how can you have a Woodstock without people smoking a little dope?” he asks.

“We were having fun in the spirit of rock’n’roll and we woke everybody the fuck up because our adrenaline was spiking.”

During Jackyl’s nine-song set, Jesse James lit a gasoline-soaked stool on fire, then destroyed it with a chainsaw. Later, he picked up a 12-gauge goose gun rifle and fired into the air in tribute to late Woodstock legends Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Keith Moon.

In the process, he accidentally slashed open his hand, smearing blood over himself. As a farewell gesture, he smashed his Gibson SG guitar and dropped his pants during She Loves My Cock.

“They had a 40-foot-square screen behind me and I didn’t want to miss the opportunity to have my penis be 10 feet long,” he says. Woodstock had begun.

There was a chill in the air and dark clouds on the horizon as Blind Melon took the stage on Saturday afternoon - a day that saw one of the most mixed and muddled festival line-ups in history, everyone from Cypress Hill to The Cranberries to, ah, Salt-N-Pepa getting in on the action.

Blind Melon vocalist Shannon Hoon seemed determined to make Woodstock ’94 a long, strange trip. Before going onstage, he dropped acid, put a barrette in his hair and smeared on mascara. He just needed one more thing for his androgynous transformation…

“As we’re going up, I turned around and Shannon was completely fuckin’ naked in the crowd,” Rogers Stevens recalls. “He told his girlfriend to take off her dress and give it to him. She did and he put it on. He looked so fuckin’ cool.”

The band’s psychedelic, bluesy hard rock was mesmerising, and, thanks largely to Shannon, they looked as good as they sounded. The Woodstock site stayed dry until Blind Melon finished… then the skies opened.

Regardless, the Rollins Band toughed it out, navigating puddles to deliver a scalding showcase of metallic post-hardcore tinged with blues, jazz and provocative comments.

“Newsweek [asked me], ‘What do you think about Woodstock?’” Henry told the crowd. “And I said, ‘I think it’s the hippies cashing in on all the money they were too high to make in the 60s. Now, they look like Don Henley and they’re cashing in. So make sure you get yer ya-yas out before you go home because they’re gonna get the rest.’”

But festival officials were soon forced to scramble into action when more than 150,000 people without tickets knocked down the perimeter gates and stormed the grounds, turning the festival into a free show.

“We thought the fences would hold up,” says John Scher. “We reinforced them, but when you’ve got 100,000-plus people trying to get in, there’s no such thing as a fence. On a certain level, it was great and we enjoyed it while it was happening, but we also knew it was a bit of a catastrophe.

"Right away, we thought, ‘How the hell are we gonna feed and get water and sanitary facilities for the extra 150,000 people?’ We had to shift gears and get more supplies in, which we did by late Saturday. And fortunately, we had more than enough room for everybody.”

Many of the trespassers arrived just in time for Nine Inch Nails, who took the stage looking like Marines who’d crawled through a field littered with IEDs. Following an instrumental intro, the band launched into Terrible Lie from first album Pretty Hate Machine.

Mixing songs from their debut and their thrashy EP Broken with their then-recently released breakthrough The Downward Spiral, Nine Inch Nails brought the vitriol, counteracting the peace and love creed from Woodstock ’69.

They closed with Happiness In Slavery and Head Like A Hole, during which Trent attacked and battered a keyboard at the back of the stage, which regurgitated echoes of agonising noise.

Only Metallica could follow that. They were still two years away from releasing Load and, in the burgeoning alternative nation, were in need of a credibility refresher.

Woodstock ’94 did just that, exposing the band to fans who loved Green Day and Pearl Jam but might not yet have been won over by Metallica’s heavier, more explosive music.

“Metallica went up and overpowered everybody with their stage set,” Jesse James says, adding that the band may have had an unfair advantage. “Nobody was supposed to bring more than one truck, and I think Metallica showed up with a couple of them, so they had a lot of bells and whistles. But they were great.”

Metallica burned through 15 songs in two hours, opening with their cover of Budgie’s Breadfan, then ensnaring the masses with a pyrotechnic barrage of hits, including Master Of Puppets, For Whom The Bell Tolls and Enter Sandman. During One, two minutes of machine-gun fire and flashpot bursts illustrated both the celebratory vibe of the event and the pre-millennial angst of the era.

After Metallica, Aerosmith took over for a post-midnight set, and the mood shifted from stark and explosive to fun-loving and oh-so sleazy.

Aerosmith’s singer Steven Tyler and drummer Joey Kramer were in the audience at the original Woodstock, and though they were young, they never forgot what spreading peace and love – or was that getting a piece of spread love? – was all about.

Despite the rain, the group were on fire, as Steven gyrated around with the mic stand dressed in a Mad Hatter’s outfit, bandanas tied to his sleeves.

While Sunday saw a set from Perry Farrell’s post-Jane’s Addiction band, Porno For Pyros, the most talked-about band were Red Hot Chili Peppers.

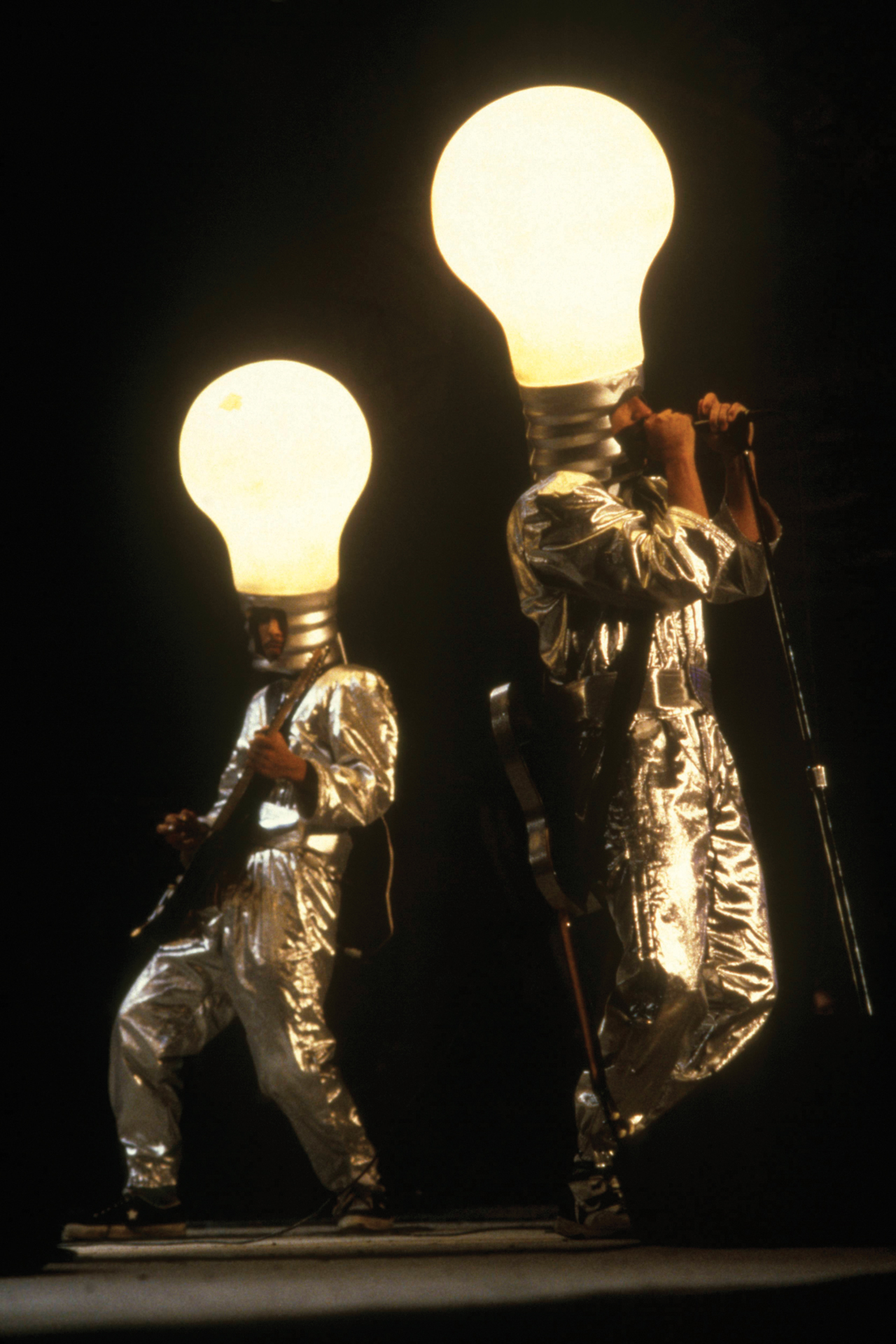

They took the stage dressed as lit lightbulbs and powered through the funk-fuelled Give It Away, which they ended with the snippet of Black Sabbath’s Sweet Leaf.

Guitarist Dave Navarro thinks the costumes looked killer, but at the time he was dead set against them. He had played a couple of small warm-up shows with the band, but the Woodstock gig was his first major appearance, and he didn’t want to look ridiculous.

“We hadn’t worn them before, so there was this element of the unknown,” he recalls.

“The costumes took so long to make, they didn’t arrive until the day of the show. We put those things on our heads, and they were, like, 50 pounds each. It was nearly impossible to play.”

Intensifying his first-show jitters was the knowledge that Perry Farrell, his former Jane’s Addiction bandmate, was in the audience.

“Perry’s one of the coolest frontmen in rock and he’s about to watch his old guitar player come out dressed like a fuckin’ lightbulb,” says Dave.

“That’s what was going through my head. But we only used the costumes for one song, then I got to run around for the rest of the show.”

For the encore of The Power Of Equality, the band returned to the stage dressed like Jimi Hendrix circa Woodstock 1969.

“I was cool with that, because Hendrix is one of my all-time heroes,” Dave says. “If it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t have become a guitar player.”

In the end, Woodstock ’94 was a youthful celebration that proved sex, drugs and rock’n’roll were still alive and well, and could be enjoyed without mindless acts of destruction – even with the inclusion of a bunch of hard rock and metal bands.

“The audience was accepting of everybody,” John says. “The same people that were digging Metallica and Henry Rollins were star-struck by Bob Dylan and Peter Gabriel.”

Still, certain concert-goers were more passionate than others. About nine months after Woodstock ’94, DJ Scott Shannon from New York radio station Z100 called John with some unexpected news.

“He went, ‘Hey man, what’s going on?’” recalls John. “‘I’m getting dozens of calls from people who are having babies and I think there’s a good chance they were conceived at Woodstock!’”

Today, those kids are 24 years old, and some of them are probably making plans to attend the 50th Anniversary of Woodstock concert, which was due to take place this year in Watkins Glen, New York in August – but after many, many issues and various bands dropping out, the entire event has been cancelled.

A glance at the tracklist of the Woodstock ’94 live album is a reminder of how solid the event’s line-up and performances were for metal fans. NIN’s Happiness in Slavery won a 1995 Grammy award for Best Metal Performance and Metallica’s For Whom the Bell Tolls was also nominated.

In addition, tracks by the Rollins Band, Jackyl, Green Day, Red Hot Chili Peppers and Primus stood strong alongside classic rock numbers by Dylan, Peter Gabriel and Joe Cocker.

Like its predecessor, Woodstock ’94 was a celebration of cultural diversity and musical innovation. Significantly, it was also a snapshot of a moment when metal groups and loud alternative bands influenced by metal, punk and classic rock brought the spirited sounds of the counterculture into the mainstream. Two days of rain, mud and overcrowding couldn’t stop the (r)evolution.