“We were pot-smoking hippies and Rick Wakeman was a pub guy. The angle twisted and we went off in a new direction”: The epic story of Yes and the three albums that changed the course of music

Along with King Crimson, Genesis and ELP, Yes were one of the founding fathers of progressive rock thanks to the trio of groundbreaking albums they released between 1970 and 1972 – The Yes Album, Fragile and Close To The Edge. In 2009, late bassist Chris Squire and longtime guitarist Steve Howe looked back on two years that changed music forever.

The Summer of Love was over. The 60s were fizzling out, the hippie dream fading like a cheap T-shirt. If the new decade needed some symbolism, then 1970 had the deaths of Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin within three weeks of one another. After Woodstock came Altamont. In a time that was all about the vibes – the new vibes were heavy, the new vibes were bad.

Yet between 1970 and 1972 came a golden age – perhaps the golden age – of rock music in Britain. Led Zeppelin recorded Led Zeppelin III and IV; Black Sabbath made Black Sabbath, Paranoid, Master Of Reality and Vol 4; Deep Purple cut In Rock, Fireball and Machine Head; The Rolling Stones released Sticky Fingers and Let It Bleed; Free recorded Fire And Water, Highway and Free At Last; Genesis made Trespass, Nursery Cryme and Foxtrot; Emerson Lake & Palmer recorded ELP, Tarkus and Pictures At An Exhibition; Jethro Tull managed Benefit, Aqualung and Thick As A Brick.

“Things moved at a different pace then,” says Yes’s Chris Squire, some 40 years on. “The ‘tour, album, tour, album’ thing was much shorter. In those days it was a tour of England, the States, a run down to Japan and Australia and you were ready to do another one. Now it takes forever.”

As the 1970s opened, Chris Squire and Yes, the band he’d formed with Jon Anderson in 1968, were on the brink of a tasty little run of their own. In that same golden period they recorded and released genre-defining albums The Yes Album, Fragile and Close To The Edge.

“We also managed to fit in a couple of line-up changes and couple of tours of America, too,” Squire chuckles. “All in all we were quite busy, I suppose.”

Squire had survived a psychedelic dalliance of his own, playing in a band called Mabel Greer’s Toyshop, where he first met Jon Anderson and guitarist Peter Banks. He’d also been in a flower-power outfit, The Syn, around the same time that Anderson had sung on a couple of singles for Parlophone under the shameful pseudonym Hans Christian.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

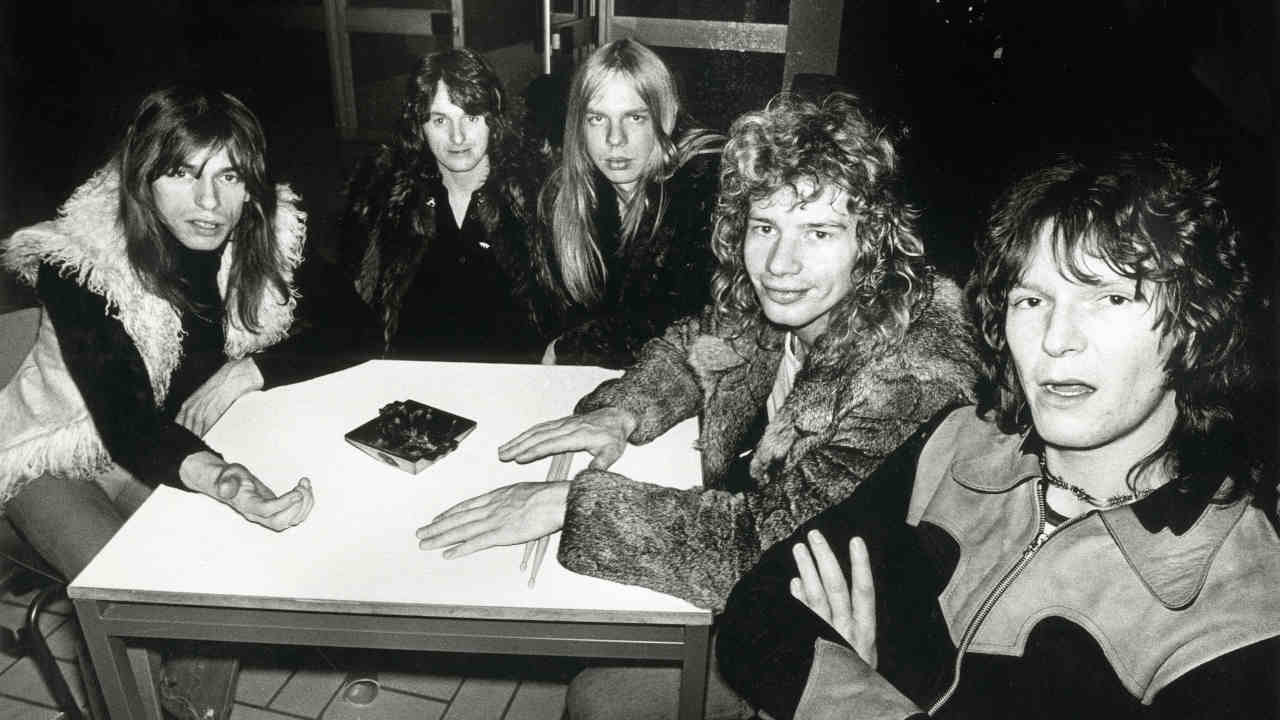

Yes were a less druggy, more serious proposition from the start. Squire, Anderson and Banks found a gifted drummer named Bill Bruford and keyboard player Tony Kaye and teased out a couple of formative albums called Yes and Time And A Word, made up of band originals and covers.

“When we were doing Time And A Word, Peter Banks was not very happy that Jon and I were very keen on using orchestration,” Squire recalls. “I suppose that caused a bit of a rift and that’s why… it was definitely a musical difference we had going. We parted ways.

“I frequented the UFO club and I’d seen Steve Howe playing in a band called Tomorrow there and at whatever the Reading Festival was back then; the Richmond Festival, I think. I’d seen him play at the Speakeasy in a much smaller environment with his own band. He was definitely number one on my list. I thought he was a blazingly good guitar player. He did take a bit of persuading [to join Yes].”

Steve Howe had been on the edges of getting somewhere. Tomorrow had a minor hit with My White Bicycle, later covered by Nazareth, and he’d rejected approaches from The Nice and Jethro Tull while in his own band, Bodast.

“Even though I was only in my early 20s, I’d been through a few ups and downs and I’d just been in a group where most probably the musicians weren’t as strong as me,” Howe remembers. “I was looking for a group where we were all equal in terms of capabilities. There had to be something right about this group, because besides living on the breadline, my music wasn’t getting a chance. It was very much about the internal chemistry. I believed that you had to have that to get things going. I felt that this was the time for me. I was getting noticed, and I wanted to do something that would pull this together.”

Howe took a guitar and a few effects pedals down to Yes’s rehearsal room in Barnes, West London, a small basement space in a house owned by their manager.

“I didn’t know Yes, “ he admits. “I’d seen them written about but I didn’t know what they were about. And although I can’t underestimate how good it was to hear Jon sing or Chris play the bass, or Tony Kaye, who was very funky on the organ, it was Bill who made me realise: ‘Hang on, this guy over there, how does he play that?’ The group was one I thought I could be part of, because everyone shared a very broad appreciation of music.”

Within weeks, Howe and the rest of Yes were out of London and ‘getting it together in the country’, living in an old farmhouse in Devon, home to Langley Studios. The idea was that they’d write an album’s worth of material and get to know each other.

“I roomed with Bill and maybe that’s why Bill and I are quite close, because we kind of had to share things and get along with each other,” Howe says. “The concept was to be a reasonably organised professional musician. I don’t think Yes had any other criteria. It was a bit like an orchestra: ‘Here you are, you play this instrument.’ One of the first things I played them was The Clap, and they said: ‘Great. Put that on the album.’ That got me really committed. I threw in everything I had. And I had quite a lot of instrumental sections, I had the middle of Yours Is No Disgrace, I had Wurm.”

“I suppose we were all on a similar, pot-smoking wavelength,” Squire considers. “That side of it was covered, really. We got on quite well. The arguments we had were over music, at that time.”

Yet, as Squire hints, the character of the group was emerging.

“We didn’t have the baggage of all that stuff we eventually accumulated over 10, 20, 30 years,” agrees Howe. “We weren’t overly living in each other’s pockets. We worked in Devon to create The Yes Album. Then we started doing gigs – and we couldn’t wait to get away from each other at times. It’s a fiery sort of creature. You need to go away and cool down. I don’t think we anticipated any big problems in those first few years, because it was all about the music then.”

The Devon sessions produced a blueprint for the future of Yes. Howe worked his guitar lines together with compositions by Squire and Anderson to form long, themed pieces. The Yes Album would feature three nine-minute songs: Yours Is No Disgrace, Starship Trooper and Perpetual Change.

There then followed what was an odd few months, when, as they prepared to record the new material, Yes also released Time And A Word, which had been completed with guitarist Peter Banks, before Howe joined, but nonetheless with Howe in the photo on the sleeve. It was a halfway house of a record, already superseded by the time it came out. The Yes Album followed just eight months later.

“There is an odd story about that too, which is kind of a stroke of luck, “ says Squire. “When The Yes Album was released, they had this postal strike. Back in those days, Fred Bloggs who owned the local record shop used to mail in to the record retailer how many of this they’d sold, how many of that. On Monday they used to open the envelopes, and the chart would come out on Tuesday. When there was a postal strike there was no way of getting this information, so they decided to take the whole of the British charts from Richard Branson’s new Virgin record store in Oxford Street. Our manager, Brian Lane, was straight down there, I’m assuming buying a whole load of records. So we went to No.4 in the Virgin store, therefore we were No.4 in the national charts. And when the postal strike was over, because we were No.4 in the charts, all the provincial stores ordered the record. I’m not saying it was dodgy, I’m just saying it was very fortunate there was a postal strike.”

The Yes Album was a Top 30 hit in America, the band followed it out there, and the new life of Yes began.

“There was a sort of personal upheaval about the time I joined Yes and started to rise to success,” says Steve Howe. “A relationship just broke up, and it was a very painful one. It was partly because I did start a new life. It wasn’t that I wanted to sacrifice it, but I’d always sensed that when you joined a band you pushed some of your life away to deal with it. The moment Yes really started to get big, there was a painful but necessary change in my life. Other people came into it and I started a fresh one. My wife Jan, who I’m happily still with, she started with me then and she saw it all happen.”

“It was very exciting to go to Sunset Boulevard and play at the Whisky, stuff like that,” Squire says. “I could feel the energy of what was going on too.”

Within weeks of returning to the UK Yes were headed for the studio again. But the speed was beginning to open further divides in the band.

Squire: “I don’t know exactly what it was, but there was a lack of communication between Steve and Tony Kaye. It looked like that for the band to move on we needed to change one or the other – and Steve was proving himself to be a very valuable part of the organisation. I’d spotted Rick Wakeman. I suppose you can say I head-hunted him. It wasn’t easy, it took a lot of persuasion, but eventually he agreed.”

Wakeman would become a force majeure, both for the music and for the band. His willingness to embrace orchestration, his classical training and session man’s speed acted like rocket fuel on Yes’s music. His character added some torque, too.

“To put it blatantly, we were pretty much pot-smoking hippies and Rick was a pub guy,” says Squire. “Some of the magic comes when you knit someone in who isn’t like the last person. The angle twists and we go off in a new direction.

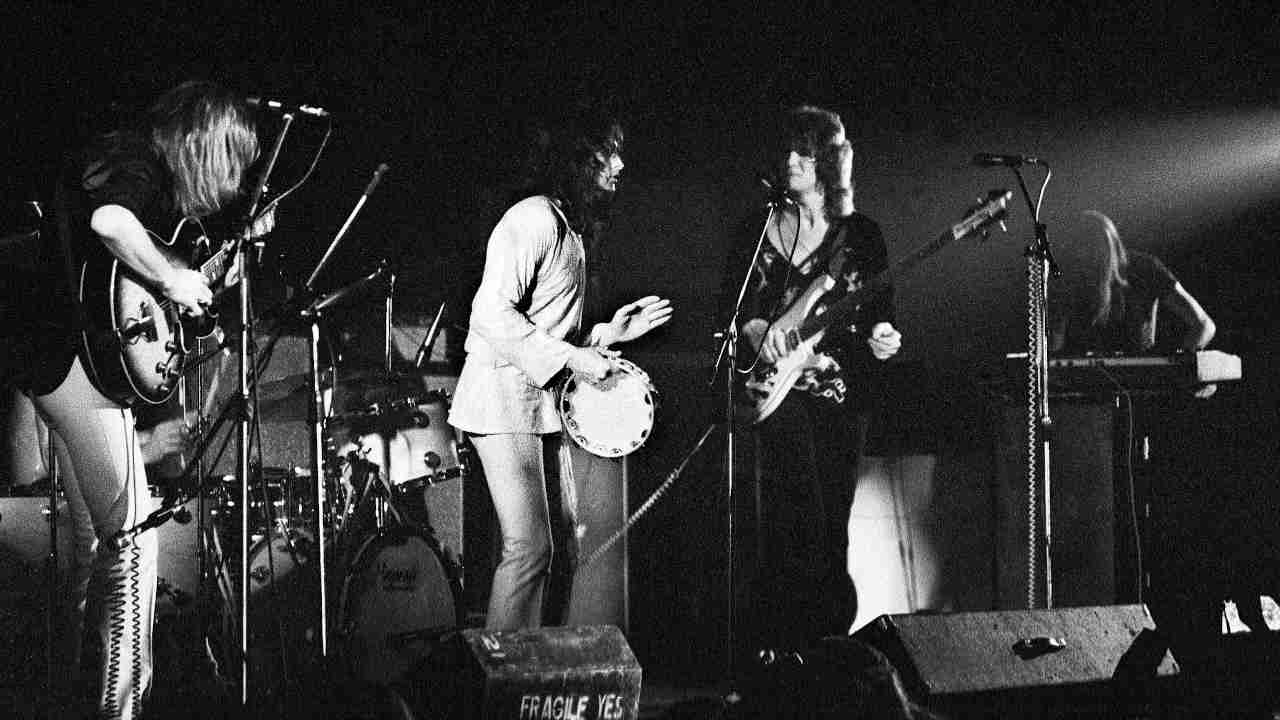

“We suddenly found that, because of the demand, we’ve got to get another album out and we’ve got to get it done in a couple of months. And in actual fact, from day one to the end of mixing we did Fragile in six weeks. We knew that we didn’t have enough organised pieces to fill an album, so we went: ‘Tell you what. Let’s do our solo efforts and use them as links between the band tracks.’”

Fragile was Yes’s first truly great record, a landmark of progressive rock. Short on time, long on inspiration, each band member spliced a short solo piece between three epic songs: Roundabout, South Side Of The Sky and Heart Of The Sunrise. Deeply ambitious, strangely quirky, gloriously indulgent, the songs summed up what the new genre was about: fiercely committed musicianship and challenging music. Anderson’s opaque lyrics and high, plaintive singing contrasted with the rasping toughness of the Squire/Bruford rhythm section and the virtuoso flourishes of Wakeman and Howe. It was a heady brew, of and for its time.

“We were learning and perfecting what we’d started doing on Starship Trooper, ” says Squire. “Heart Of The Sunrise almost fills out Yes’s blueprint – doing pieces that were longer, the style of us having a song with movements. It has a very fast instrumental and a melody and some quirky instrumental parts, then the song again.”

“I think we believed we were incredibly commercial as well,” says Steve Howe. “I’m saying this slightly tongue in cheek, but we sort of thought, obviously the artistic endeavour and development was so good that it was going to be an enormous hit. And then it was!”

Yes returned to America as headliners, sold out Madison Square Garden and set themselves on a path that would lead them to the commutes on Concorde, the private jets, the garages full of cars.

“I had four cars,” says Howe. “Trevor Horn said to me: ‘They never work, do they? You never know which one’s got petrol in, which one’s been serviced.’ He went back to one car and so did I.”

“We rolled with the times,” Howe remembers: “I could see that Bill and I were good moderates early on. We liked to have fun too, but we were stable people. The 10 years of me nurturing and trying to do the right thing for Yes, and all the success we had, was hugely rewarding, but there seemed no end to it. We were pushed around a bit. We created a scenario where we barely had time to live.”

With a formula established, Close To The Edge, recorded between April and June 1972, was in the shops by September that year, little more than nine months after the release of Fragile.

“We weren’t writing pop songs,” says Steve Howe. “When we did Roundabout, that was big, but in Jon’s and my mind we hadn’t got to the biggest. When we started writing Close To The Edge we started talking bigger, bigger. A whole different mood. We started getting new age, really; we got kind of floaty and gloomy, and those bits make the other bits sound even more powerful.”

The album featured just three songs: on vinyl the title track consumed side one, while And You And I slugged it out with Siberian Khatru on side two. Like Fragile, the album was esoteric in feel, cut through with Anderson’s strange words and the band’s rich, evocative prog rock.

“Jon had a way of taking my simplistic lyrics like, ‘Close to the edge/down by the river’ – meaning the Thames – and making them sound like something else,” Howe explains. “So sometimes people would criticise the lyrics and they were mine. He did write the majority of the lyrics, and he had a little bit of new age, new world concept all flowing together, a bit like the great artists. Dali was always throwing together obscure things, and Jon was throwing together the most obscure words. Sometimes perilously. But in a way, he didn’t think so much of meaning but the way they would sound.”

“The song Close To The Edge we did rehearse and play from beginning to end before we went into the studio,” Squire remembers. “Although we’d record in sections, we knew where the end was going to be. We had a game-plan. And that was really the last time we were ever able to do that. By the time we got to Tales From Topographic Oceans [1973] we didn’t have a sense of the ending, and that created another set of problems.”

As Squire suggests, Yes’s period of genuine excess was about to begin. A live triple album, Yessongs, preceded the perturbing and impenetrable Tales From Topographic Oceans.

“The private jets started in ’74, I think,” Howe says. “I was on the cover of Melody Maker about six times in the 70s, purely because I was the guitarist in Yes. Your life does become different then, and a lot of the arguments and so on were not about music any more. But the period up to Close To The Edge, times were different and we were part of a generation of groups who had albums as hits, rather than singles. If you look back at an album and it’s 20 years old and still selling copies, then you’re not doing much wrong.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 138, October 2009

Jon Hotten is an English author and journalist. He is best known for the books Muscle: A Writer's Trip Through a Sport with No Boundaries and The Years of the Locust. In June 2015 he published a novel, My Life And The Beautiful Music (Cape), based on his time in LA in the late 80s reporting on the heavy metal scene. He was a contributor to Kerrang! magazine from 1987–92 and currently contributes to Classic Rock. Hotten is the author of the popular cricket blog, The Old Batsman, and since February 2013 is a frequent contributor to The Cordon cricket blog at Cricinfo. His most recent book, Bat, Ball & Field, was published in 2022.