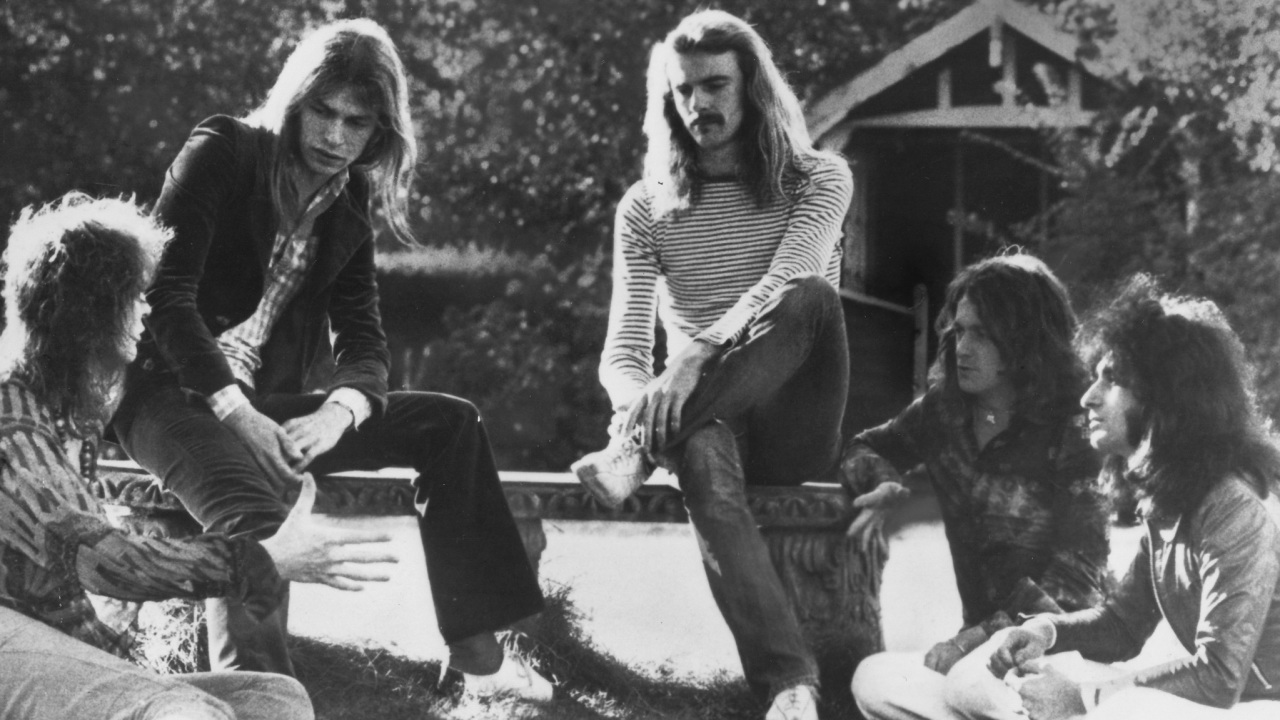

To mark the 40th anniversary of Yes’ remarkable seventh album Relayer in 2014, Steve Howe and the late Alan White shared their memories of their early struggles to move on without Rick Wakeman, and eventually delivering one of their favourite records in their catalogue.

From The Yes Album through to Tales From Topographic Oceans, Yes’ capacity to harness differing ideas and influences gives the impression that those albums are incremental – each one building upon the successes and lessons learnt from its predecessor.

By contrast, 1974’s Relayer is perhaps the most radical departure in the group’s 1970s catalogue. Startlingly different to anything preceding it, the record incorporated adventurous time signatures and other harmonic elements more usually associated with jazz-rock acts such as Return To Forever or Bundles-era Soft Machine.

Never content to rest upon their laurels, Yes required their listeners to take a leap of faith as they enthusiastically dived into uncharted waters. Though significantly shorter than Tales, Relayer is just as multifaceted and, in its own way, just as challenging.

It possessed many recognisable features, including Roger Dean’s striking cover artwork; but it also included some of their most angular and dissonant music up to that point. Despite the ambitious and sometimes difficult musical terrain it mapped out, upon its release in the winter of 1974, it hit the Top 5 in the album charts on both sides of the Atlantic.

In the ensuing years, Relayer’s reputation and stature has continued to grow. Yet at the end of May 1974, following Rick Wakeman’s decision to quit the band, that outcome was by no means certain when the band settled in their rehearsal room to consider their next move.

Alan White: Morale was low – obviously people were disappointed Rick had gone because he was an important part of the band. I think we’d started working on some of the Relayer material before he left, but he had a bad taste in his mouth after playing and touring Tales From Topographic Oceans, and I guess he just wanted to carry on with his own music.

We all got a grip and started looking for a new person, while working as a four-piece to get the flow going. We spent a long time rehearsing, getting the basic ideas for Relayer together.

Steve Howe: We’d tried working with ex-Aphrodite’s Child keyboard player Vangelis Papathanassiou. Musically it would have been fantastic with Vangelis – he had a fantastically strong direction – but the reason it didn’t work out with him was that when we said, “Let’s play that again,” he’d say, “Well, it won’t be the same.”

We were kind of improvising – but were learning parts as we went along, and I think that’s when we realised he was such a spontaneous player that Yes was going to be a problem for him. We were really about working out a solid arrangement and relying on him at any given point to play something that we’d recognise.

Vangelis felt he didn’t really need to. He was always going to play off the cuff – which would have been wonderful, but we’re not a jazz group!

Patrick brought something like fresh blood to the thing – like I had and like Rick did

Steve Howe

Alan White: It took a while before we found the right keyboard player. I used to joke, “Whoever turns up next week is recording the next album!”

Steve Howe: There was somebody before Patrick Moraz, and I called him and made the offer. But he said, ‘Why do I need to join Yes when I’ve got ELP?’ Musically, it would have been amazing to work with Keith Emerson, but whether or not the personalities would have blended, I just don’t know.

We were starting to realise that the personalities in the group is a very important thing. It doesn’t matter how much the music seems to be the goal – it won’t work unless you all get on.

Alan White: The first time Patrick played with us, he had this jazzy, prog kind of intro that became the opening of Sound Chaser. It didn’t really have a fixed time to it but rather it was something that was felt between the keyboards and drums. I came in with the drum pattern that’s in fives and sevens.

I got to know the lick real well and played it note for note on the drums around the kit. I don’t think we took that many times to nail it. It was one of the real early takes and we used one of them. It was pretty off the cuff.

Steve Howe: I think the confidence of the band really comes from the union of the five people. Once we had Patrick there, we were up and running. With his flamboyance he brought something like fresh blood to the thing – like I had and like Rick did. Patrick was brilliant and more than capable of holding the fort, so to speak.

An album doesn’t sound good unless you’re having fun and that’s what you hear when you put that record on

Alan White

Alan White: The Gates Of Delirium was one of the hardest numbers we ever did. It demands a hell of a lot of energy and precision; and, of course, if it’s played sloppily, it just doesn’t work. I look back on it and I think, “Oh my God, we were really crazy!” It’s certainly out there.

Steve Howe: For me, every Yes album was always a journey to find better sounds and ways of interpreting the music on guitars that excited me. When it came to Relayer, I decided I was going to go Fender, but not a Stratocaster because the sound was so common at that time.

The Telecaster is one of the greatest guitars ever designed and I was so excited to have a great 1955 model. It just felt right for the album. The guitar on Gates rarely stands still. I move from being sweet and the next minute I’m scratching at the melody.

Alan White: We were very prog-minded and experimental in those days. We were looking for anything that sounded different. From a percussion point of view, it extended to Jon Anderson and myself going to a scrap yard and banging pieces of metal in the morning for about an hour to see what sounded good.

We actually built a frame in the studio made out of springs and car parts which, of course, ended up on the album in the battle section of Gates – it was pretty crazy stuff.

I came up with the theme that comes out of the battle on Gates. I used a rhythmic technique and my basic knowledge of chords and wrote the changes between chords in seven. Patrick liked that progression and Steve took it and developed it.

To Be Over is one of the most beautiful things we did that wasn’t actually a slow song

Steve Howe

Steve Howe: Jon wrote most of Gates, though we get credited in a very discrete kind of way that Yes invented. There was a balance in the way that members of the group contributed to each other’s music – that was the whole key to what we did in Yes.

None of us could stand up and say we wrote that whole thing because it was all a collaborative process. The way we operated from Topographic onwards was to give everybody more credit. Some guys did a lot and some did very little, but it was a way of involving the whole band.

The other highlight of the album is definitely Soon. To end Gates with what is, in effect, another song entirely, really is such a cool thing to do. We were trying so many things. Patrick added quite a flair to the album generally, but it was very noticeable on Sound Chaser. That was the most crazy, OTT number where we all had to think on our feet every single second of the track.

In the middle there’s what’s in effect a cadenza for electric guitar, synth and percussion. We’d got to that point and said, ‘What’s going to happen now?’ I had this idea, which was a kind of rock flamenco. I was using flamenco guitar technique with a plectrum. There was a diminished chord which we used to refer to as the ‘Hammer Horror’ chord and I used that a lot in that section.

Alan White: The whole thing about Yes is we would work things out melodically and do all the technical side, working out parts. When it comes to putting it down, then you add the feeling on top and that’s what makes a difference with Yes. It’s very complex, technical stuff with feeling.

Steve Howe: The other instrument I use on To Be Over is the pedal steel, which is a complicated instrument. I cite this track as one of the most beautiful things we did that wasn’t actually a slow song. It’s mellow, soft and gentle, but it’s also quite bouncy, and I like that quality. Overall, it’s a pretty important album without too many comfort zones.

Alan White: Relayer is in the top three albums Yes ever did – the other two being Tales and 90125. We were all totally into it. We were in the studio and coming up with new ideas on a daily basis. An album doesn’t sound good unless you’re having fun and that’s what you hear when you put that record on: Yes having fun.