In November 1973, as Kiss began work on their debut album at Bell Sound studio in New York City, it was the band’s sheer will to win that left the biggest impression on the two guys who co-produced that album, Kenny Kerner and Richie Wise.

As the latter recalled: “The desire to be huge, the desire to hit the grand slam right out of the box, was the foundation that Kiss was built on. Nothing was going to stop them from becoming the biggest band in the world. They wanted to make rock’n’roll history.”

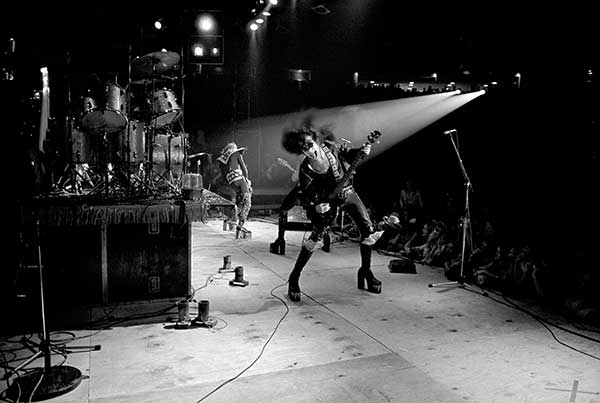

It was a dream that became a reality, but not without a long, hard struggle. For all the hype that the band generated with their larger than life image, and all the popularity they gained as an outrageous, take-no-prisoners live act, there was a period, the best part of two years, when they couldn’t buy a hit record.

The debut album, titled simply Kiss, shifted just 75,000 copies. The second, Hotter Than Hell, sold more, but stalled at No.100 on the US chart. The third, Dressed To Kill, almost made the Top 30, although its big anthem, Rock And Roll All Nite, flopped as a single.

It was only at the fourth time of asking that Kiss finally hit that grand slam, with their first million seller – the explosive double live album, Alive! And yet, through it all, what Richie Wise sensed in Kiss – the self-belief, and the burning desire for fame and glory – never wavered.

As guitarist/vocalist Paul Stanley said: “Doubt is poison. Obstacles are what you see when you lose sight of your goals. Ultimately you may lose some battles but you win the war. Other people may have thought we weren’t going to make it, but failure was unacceptable to us.”

For bassist Gene Simmons, the success of Kiss was in essence a triumph over fear. “Most people are afraid of ridicule,” he said, “but I wanted it so much that ridicule meant nothing to me, so long as there was just a glimmer of hope that I’d be wildly loved and all the women would want to have my children. That’s what we all strive for, but there are few of us who are willing to scale the heights.”

Stanley The Parrot, it was called – the funny little tune by Gene Simmons which was magically transformed into the swaggering, sexually charged rock’n’roll song that introduced Kiss to the world.

The title was not a joke from Simmons at the expense of Paul Stanley. The pair had not yet met when Gene wrote this strange song with a psychedelic sound and abstract words. But the first time they got together, in 1970, Stanley The Parrot was one of the numbers that Gene played for Paul, and there was something about it that stuck in Paul’s mind – a chord structure that was a perfect fit for a Kiss song in the style of the Rolling Stones’ Brown Sugar.

“We knew what kind of sound we wanted,” Paul said. For the lyrics, he looked to the glamour queens of New York’s rock scene and the mysteries in Bob Dylan’s Just Like A Woman. And it was this song, Strutter – a New York story with a New York groove – that was chosen as the opening track on the first Kiss album.

In the summer of 1973, before Kenny Kerner and Richie Wise were enlisted as producers, the band had cut demos of Strutter and other key songs – Deuce, Firehouse and Black Diamond – with a guy who had worked on some of the biggest and most influential rock records of the late 60s and early 70s.

Eddie Kramer, a South African expat, had served as recording engineer for The Beatles (on All You Need Is Love), the Rolling Stones (Their Satanic Majesties Request), the Jimi Hendrix Experience (Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold As Love and Electric Ladyland) and Led Zeppelin (Led Zeppelin II and Houses Of The Holy).

Given this pedigree, the four members of Kiss were thrilled to work with Kramer. As Paul said: “I’d been an Anglophile since I was a young teen. All the bands that inspired me were British. And I worshipped The Beatles.”

But while Kramer had the kudos, it was Kerner and Wise who had the connection that paid off – for them, and, in no small measure, for Kiss. Neil Bogart, a brash record company executive, had founded a new label in 1973 – christened Casablanca Records in reference to his famous namesake, Humphrey Bogart.

Kerner and Wise had first hooked up with Bogart when, as boss of the Karma Sutra label, he signed Dust, a New York power trio in which Wise played guitar alongside bassist Kenny Aaronson, who later backed Joan Jett and Billy Idol, and drummer Marc Bell, who went on to become better known as Marky Ramone.

Kerner wrote all of the band’s songs with Wise. They also co-produced for the first time on what turned out to be Dust’s final album, Hard Attack. Their next production for Bogart – a novelty song, Back When My Hair Was Short by Gunhill Road – made the top 20.

From there, more hits followed. And it was this partnership, between record company mogul and savvy producers, which led to Kiss becoming the first act signed to Casablanca Records.

“Neil Bogart would leave demo tapes for me outside of his office,” Kerner said. “I would come by once a week and pick them up.”

It was on a Friday night that Kerner pulled out the Kiss demo recorded by Eddie Kramer, and as he recalled: “It just blew me away. I said, ‘Shit, this is exactly the kind of stuff Neil should have on Casablanca – a legitimate and credible rock group.’ I brought that tape back to him Monday and said, ‘You want to sign these guys.’ So that’s how we became involved with Kiss.”

It was at Le Tang Ballet Studios, right across the street from Bell Sound, that Kerner and Wise saw Kiss perform live for the first time. They came away with a simple remit for the job ahead. “We decided that this had to be a real street album, a real raw album,” Kerner said. “Exactly the way they were live.”

According to Wise, the whole album was recorded in six days, with a further seven days of mixing. For lead guitarist Ace Frehley, the album had the hard edge and streetwise feel that Kerner and Wise had aimed for.

“That spontaneity,” he said, “and that tough kind of sound.”

What he also heard, on a deeper level, was the band’s collective state of mind. “We were all very hungry at that point in our lives. We put in one hundred and ten per cent on that record.” And above all else, there was, as Ace bluntly put it, “a bunch of fucking great songs”.

From Strutter all the way through to the epic finale, Black Diamond, many of these songs would remain in the band’s live set for decades to follow. Deuce, one of Gene’s, was Ace’s favourite. An aggressive, up-and-at-’em number, it was the first song that Ace played with the band during his audition, and served as the opening salvo in thousands of Kiss shows.

Firehouse – written by Paul when he was a high school kid grooving on The Move’s 60s hit Fire Brigade – had a slow, heavy swing and a neat ‘whoo-ooh-yeah!’ hook, and became a concert showpiece for Gene’s fire-breathing act.

100,000 Years had a sound like thunder and a far-out sci-fi story. And in Cold Gin, amid the hard riffing, there was an ironic twist. It was Ace’s drinking song, but it was Gene, a strict tee-totaler, who sang it.

For a band in thrall to The Beatles, it was always the intention to have all four members of Kiss singing lead, the way John, Paul, George and Ringo had. But while Ace, at this stage, still lacked confidence in his voice, drummer Peter Criss had no such inhibitions.

As a fan of legendary soul singers such as Otis Redding and Sam Cooke, he brought a little R&B grit to Nothin’ To Lose, his whiskey-and-cigarettes voice mixed in with Gene’s and Paul’s, although it was Gene who delivered the risqué lines about anal sex: ‘I thought about the back door/ I didn’t know what to say… She didn’t want to do it/But she did anyway.’

And on Black Diamond – like Strutter, a New York song, begun with images of working girls ‘out on the street for a livin’’ – it was Peter who sang the hell out of it after Paul had crooned the intro.

The album also had Let Me Know, a song that Paul originally wrote in 1970 as Sunday Driver, and a track that came right out of leftfield, a lilting instrumental piece, titled Love Theme From Kiss.

Most people are afraid of ridicule, but I wanted it so much that ridicule meant nothing to me

Gene Simmons

The image for the album’s cover was of huge significance for a band as visually oriented as Kiss. Photographer Joel Brodsky was chosen for his work on albums such as The Doors’ Strange Days and Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, and his vision of Kiss – four painted faces surrounded by darkness – was in the truest sense iconic.

As Peter Criss said: “We wanted the cover to look like Meet The Beatles.”

The album was released on February 8, 1974. Paul Stanley described it as “our Declaration Of Independence”. But it was not the hit they had hoped for.

On the US chart, it peaked at a disappointing No.87. And the single that was added to the album in May of that year – a version of Bobby Rydell’s cheesy old 50s hit Kissin’ Time, recorded at Neil Bogart’s insistence – also bombed, despite heavy promotion with regional ‘kissing contests’ across the USA.

In the long term, validation would come. Over time, the first Kiss album would be recognised for what it truly is: a classic debut as definitive as the opening salvos from Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, Boston, Van Halen and Guns N’ Roses. But in the short term, there was no time for the band to dwell on failure.

The wheels were moving so fast. Moreover, for Kiss, self-doubt was an alien concept. As Paul Stanley said: “It’s like American football. You grab the ball, put your hand out in front of you, put your head down and start running forward. Anything that gets in your way goes down.

Kiss had been on the road for six months – “non-stop”, Gene Simmons said – when they pitched up in Los Angeles in August 1974 to record their second album. Kenny Kerner and Richie Wise had moved their operation to LA, and it was there, at Village Recorders studio, that Hotter Than Hell was created in a high-pressure atmosphere, with the band simultaneously homesick for New York and tripping out on all that California had to offer.

“The LA scene was really decadent and wild,” Peter Criss later said. He and Ace Frehley revelled in this environment. As Ace recalled, somewhat hazily: “It was a lot of fun out there.” But for Simmons, puritanically opposed to alcohol and drugs, albeit addicted to casual sex, it was at this point that he first sensed a division within the band.

“It was obvious that I had nothing in common with Ace and Peter socially,” he said. “For them, a good time was spelt ‘b-o-m-b-e-d’.”

The California sunshine had no effect on the band’s music. If anything, Hotter Than Hell was darker and heavier than the first record. Some of the songs were upbeat in tone: the title track a straight-shooting pick-up number with a riff and a lyric directly influenced by Free’s All Right Now; Let Me Go, Rock ‘N’ Roll as uncomplicated and rowdy as its title implied; Got To Choose and Comin’ Home as catchy as an STD.

But there was bludgeoning force in Parasite, written by Ace and again sung by Gene. And in the band’s first ballad, Goin’ Blind, written by Gene back in 1970, the sweetness in the melody was offset by the grim images he conjured: ‘There is nothing more for you and I/I’m ninety three, you’re sixteen…’

In another Gene song, Watchin’ You, he played voyeur over a mean riff lifted from Mountain’s Mississippi Queen. And in Strange Ways, a downbeat heavy-hitter, Ace’s tune, sung by Peter, an off-kilter, whacked-out vibe was completed with a solo, drenched in feedback, which sounded, as Ace put it, “like a dinosaur”.

Even the sound of the album was a little odd. The debut sizzled, but Hotter Than Hell was as murky as the LA smog. This lo-fi sensibility would make this album a key influence on grunge music in the 1990s – Melvins, a seminal band, loved by Kurt Cobain, cut a version of Goin’ Blind on their 1993 album Houdini. But in 1974, Hotter Than Hell was not the kind of record that was going to take Kiss where they wanted to go.

The album was released on October 22, 1974, and one member of the band was lucky that he lived to see it. Ace Frehley, always a loose cannon, ran wild in LA, and as he later recalled, in typically blasé manner: “I got into a car accident. I got drunk one night and was driving around the Hollywood Hills, driving faster and faster until I lost control and hit a telephone pole. I think I was just testing destiny…”

The facial injuries he sustained, while minor, presented a problem when photographer Norman Seeff shot the group for the album’s cover at a Hollywood studio. As Ace explained: “This doctor told me I could only put make-up on half my face.”

As a result, his image was later enhanced with superimposing. And whatever his discomfort going into that photo session, it was quickly forgotten. To create a bacchanalian atmosphere, Seeff brought in girls and booze. And by the time they were done, even the normally composed Paul Stanley was so wasted he had to be carried by Gene to a waiting car.

When Kiss left LA in September ’74, they headed straight back out on the road. They got a raise from manager Bill Aucoin – up ten dollars to eighty per week. The sales of Hotter Than Hell, still meagre, did nothing to change that. But out on tour, night after night, a buzz was building about Kiss. As Kenny Kerner said: “These guys were superheroes to kids.”

All they needed was one hit song to break them nationwide. Neil Bogart was certain of that. And so, when the band returned to LA for a show at the end of that year, Bogart told Paul Stanley, in precise detail, what kind of song this should be. As Paul recalled: “Neil said that we needed an anthem. And to his credit, at that point, the idea of rock’n’roll anthems didn’t exist. He said, ‘You need something that your fans can rally behind – a song that embodies what you’re about.’”

Paul chose the right place to write it – in his room at the famous Hyatt House hotel on Sunset Boulevard, a joint that became known as ‘The Riot House’ after all the wild parties that been staged there, one of which involved Led Zeppelin’s hard-drinking drummer John Bonham riding a motorcycle along the corridors.

Paul took out an acoustic guitar and within a few minutes he had it. “Very quickly I came up with the chords and the melody,” he said. “And right away I had the lyrics: ‘I wanna rock and roll all nite and party every day.’ It was very much to the point, and it was very primal in that it really wasn’t anything that I pondered.

"At that time I don’t believe people talked about wanting to party. It was just a one-word description of a way of getting loose. Rocking and rolling all night and partying every day isn’t so much a physical action as much as it’s an attitude. It’s a way of looking at life. It’s a mindset – a mindset about liberation and celebration of the individual.”

The song was completed with a verse from a work-in-progress Gene had, Drive Me Wild. “I never had the chorus,” Gene said, “but I had this notion of a car as an analogy to a woman, the idea of, ‘You drive me wild, I’ll drive you crazy.’ So the pieces were basically stuck together. Take my verse and attach it to Paul’s chorus and you’ve got a song.”

When Neil Bogart heard Rock And Roll All Nite, he was ecstatic. What surprised Paul and Gene was what Bogart said soon after. He had appointed himself as producer of the band’s third album. It later transpired that this was a political manoeuvre. As rival record companies were showing an interest in signing Kiss, a power struggle had developed between Bogart and Bill Aucoin.

As producer for Kiss, in the studio with them, day in, day out, Bogart could keep them close to him. For this album, Dressed To Kill, the band had run a little short on material, having banged out two records in a year and toured incessantly.

To make up the numbers, Paul and Gene dug into their past to rework two Wicked Lester songs, She and Love Her All I Can. But as Paul said: “Gene and I could write fast, and we did that on Dressed To Kill – writing in the morning, and by the time the other guys showed up there was a song.”

Room Service was quintessential Paul Stanley, hip-shaking rock’n’roll loaded with double-entendres. “I lived on the road at that point,” he said. “And I was getting room service in any way, shape or form it came.” C’mon And Love Me – its title self-explanatory – was also, Paul said, “very autobiographical”.

Rock Bottom had Paul and Ace in perfect harmony, the beautiful acoustic intro drawn from an instrumental piece by Ace, the “actual song”, as Paul put it, another that he cribbed from All Right Now. And from Gene, there was Two Timer, in which he kvetched about a cheating woman without a trace of irony.

It was back on home turf, at Electric Lady Studios in New York City, that Dressed To Kill was recorded in February 1975. In the role of producer, Bogart played it smart by keeping it simple. And as Ace said: “There was a lot energy in that record.”

The cover photo, shot by Bon Gruen at the corner of 23rd Street and Eighth Avenue, presented the bizarre image of the masked rock’n’rollers suited and booted, Gene in Gruen’s wife’s clogs.

Released on March 19, 1975, Dressed To Kill was the band’s first Top 40 album in the US. Rock And Roll All Nite, for all its populist genius, only made it to No.68 on the Billboard Hot 100. But as a concert draw, Kiss had an irresistible momentum.

“It just became this tsunami,” Gene said.

And so, a bold decision was made. “It was a live-or-die situation for Casablanca,” Gene recalled. “They didn’t have any hits. We hadn’t even had a gold record. But we just decided that we were going to do a live album. And we were going to make it a double live album.”

We hadn’t even had a gold record. But we just decided that we were going to do a double live album

Gene Simmons

They knew exactly where it should be recorded – in the cities where they could pull the biggest audiences. And in 1975, there was no city in America that loved Kiss like Detroit did.

As Paul Stanley said: “We could play small auditoriums around the country, but in Detroit we were the governor, we were it! It was a very special relationship. I’ve said it a thousand times – Detroit opened its arms and legs to us!”

For a producer, they went back to Eddie Kramer. “I was disappointed that I didn’t get to produce Kiss’s first album,” Kramer later admitted. “Politics prevailed. But when it came to the live album, I decided to go for it because of the challenge of making those guys sound great.”

A total of four shows were taped – at Detroit’s Cobo Hall on May 16, in Cleveland, Ohio on June 21, Davenport, Iowa on July 20, and Wildwood, New Jersey on July 23.

Later, there was some overdubbing at Electric Lady. As Kramer said: “With all that jumping around it was impossible to get an accurate performance.” But what he got out of those recordings was one of the greatest live albums of all time – named, with an emphatic flourish, Alive!

It began with a rabble-rousing, hyperbolic introduction from roadie J.R. Smalling that would echo down the years: “You wanted the best and you got it, the hottest band in the land… Kiss!” It featured definitive performances of so many stone-cold classic songs, including Deuce, Firehouse, Black Diamond, Cold Gin and Rock And Roll All Nite.

Crucially, as Paul said: “It really captured the live experience in terms of what it felt like in the audience. That was the whole idea of Kiss Alive! It was an album that totally immersed you in the show.”

And it was Paul, as frontman and cheerleader, who did most to make the fans a part of the show, rapping to them between songs like a rock’n’roll preacher.

“It’s like a church revival,” he said. “It’s trying to get everybody to peak together.” The cover of Alive! – shot by Fin Costello during rehearsals – had the band in a typically over-the-top pose. But it was the photo on the back cover, also by Costello, which resonated most powerfully with Kiss fans: two Detroit teenagers, Lee Neaves and Bruce Redoute, holding a homemade Kiss banner, the vast expanse of the Cobo Hall behind them.

“When Alive! came out and we saw that photo, we were astounded,” Redoute said. “It was a dream come true.”

Alive! did the same for the four guys in Kiss. Released on September 10, 1975, it was the album that made them superstars. The extracted live version of Rock And Roll All Nite reached No.12 in the US. Just as Neil Bogart had instructed, it was the anthem that defined the band. And in its slipstream, Alive! rocketed to No.9 in January 1976.

It was the hit that saved Casablanca Records, the hit that transformed Kiss into a pop culture phenomenon. And for the members of the band, life would never be the same again. As Gene Simmons said: “The wild thing about success is that before you have it, you can’t really comprehend it. But then, when you’re immersed in it, it’s a completely new world with no rules. And you’re king of the hill.”