No other British guitar band burned as brightly and brilliantly in the '80s as The Smiths. The Manchester quartet formed in summer 1982 and released their debut single just under 12 months later later - 40 years ago this past summer. But by the time their fourth studio album Strangeways, Here We Come arrived in 1987, they had already split. The tensions that made them so creatively potent also ended up pulling them apart. The Smiths had started something they couldn’t finish.

What a legacy singer Morrissey, guitarist Johnny Marr, bassist Andy Rourke and drummer Mike Joyce left behind, though. Their four era-defining records barely touches the sides - there was also a run of landmark 45s and quite possibly the finest B-side of all-time.

This was music that both perfectly captured the strife of the early '80s and has remained timeless since, tales of suburban mundanity that were also missives of hope and inspiration, songs of the ridiculous and the sublime. Their astonishing alchemy can be summed up by two pairings: there were the stars of the show in Morrissey, the lyrical provocateur and master melodicist, and Marr, the guitar whizz with the Byrds-y jangles and chiming, picked hooks. But the duo behind them were equally as crucial: Rourke’s bass playing combined a punky snarling with frenetic intricacy, often filling in the space around Marr’s guitar parts, and drummer Joyce held everything down with an unshowy dynamism. It made for an exhilarating meld, albeit not one built to last.

They became a new benchmark for indie-rock bands, influencing an array of groups across subsequent decades that includes The Stone Roses, Deftones, Radiohead, My Chemical Romance, Blur, St Vincent, The National, At The Drive-In, Boy Genius, The 1975 and more.

Here’s our guide to their four studio albums, plus a pivotal outtakes collection.

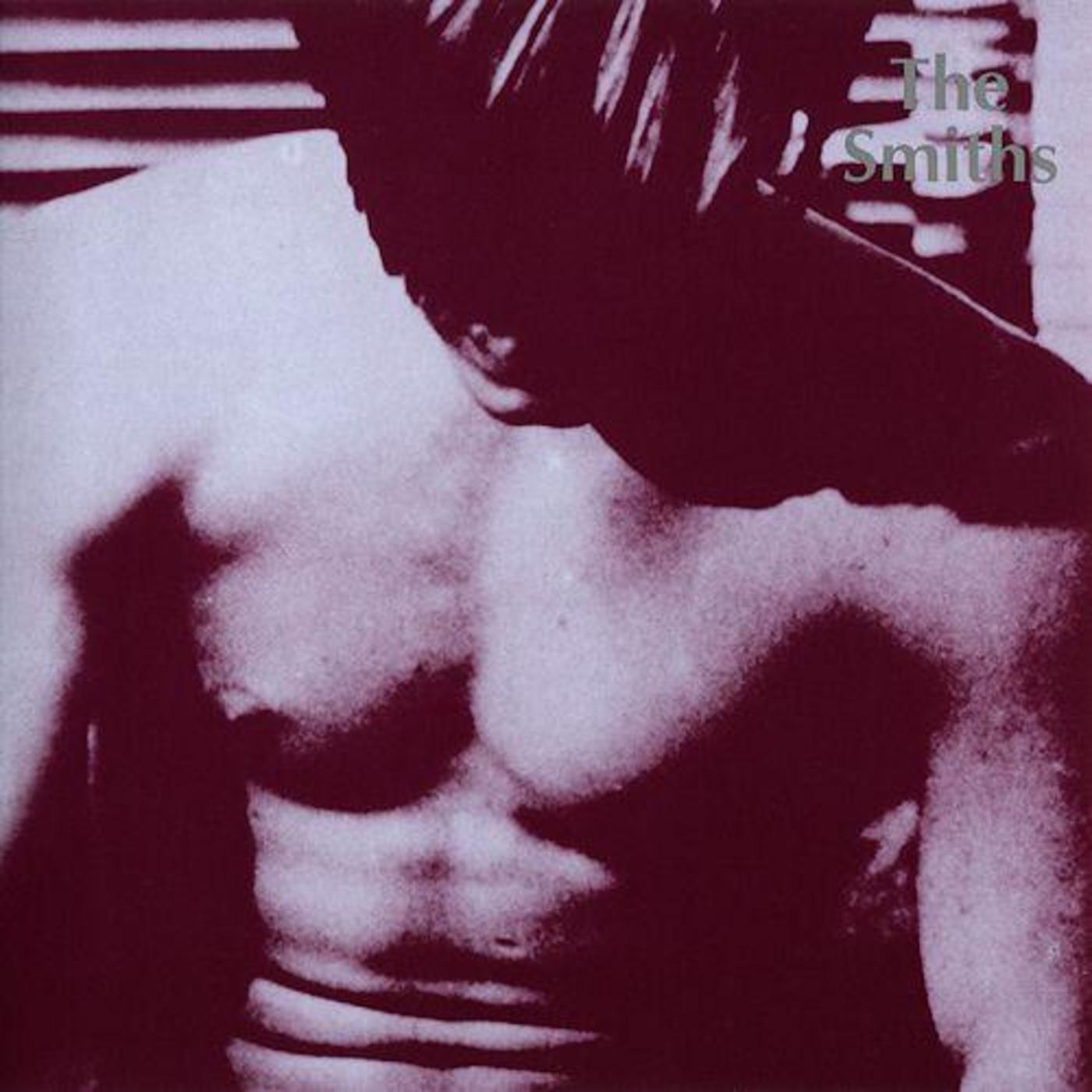

The Smiths (Rough Trade, 1984)

Even at their earliest Manchester shows, The Smiths already felt like a fully-formed proposition. There were bumps in the road when it came to recording, though. One version of their debut album, made with Teardrop Explodes guitarist Troy Tate in the production seat, was binned off when the band were unhappy with the flatness of the recordings. A second crack with John Porter proved more successful, the producer understanding that the key to getting the band’s magic down on tape was two-fold. Firstly, they needed to capture the band’s live power and, secondly, combine that with overdubs of Johnny Marr’s parts – the guitarist could see a bigger picture, a sound beyond that which one person could play.

It resulted in the group’s rawest album recording but one that signposts the greatness to come, from the taut, post-punk rush of Miserable Lie, where a tightly-wound Marr riff anchors Morrissey’s theatrical falsetto to the mix of shrill guitar hooks, alluring croon and urgent stomp that drives What Difference Does It Make?. The latter showed that this bunch of leftfield outsiders could also make brilliant pop songs, and they’d only just got started.

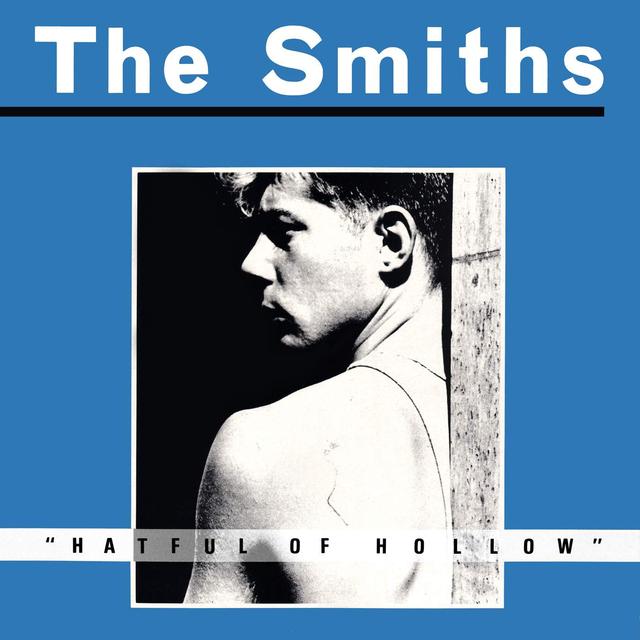

Hatful Of Hollow (Rough Trade, 1984)

There would be three compilations of non-album material put out in The Smiths’ lifespan (the others being The World Won’t Listen and Louder Than Bombs, both released in 1987), but none are as definitive as this 1984 set. Released in November of that year, it went to Number 7 on the UK Albums Chart and stayed in the chart for almost a year. This was no mere outtakes compilation – Hatful Of Hollow signalled the moment when The Smiths began to reshape the musical landscape.

Intended as a stopgap whilst they made Meat Is Murder, it collected radio sessions of tracks from their debut - some, such as a menacing version of Reel Around The Fountain, improved on their recorded counterparts – alongside standalone singles and B-sides. Of those, none is more mind-blowing than the psychedelic rock groove of How Soon Is Now?, a song that manages to sound atmospheric and like an avalanche at the same time and which shockingly wasn't even originally an A-side - it was on the flipside to the 1984 single William, It Was Really Nothing. Some bands have a job getting their second record to live up to their debut, but now The Smiths had a task on their hands matching an outtakes record.

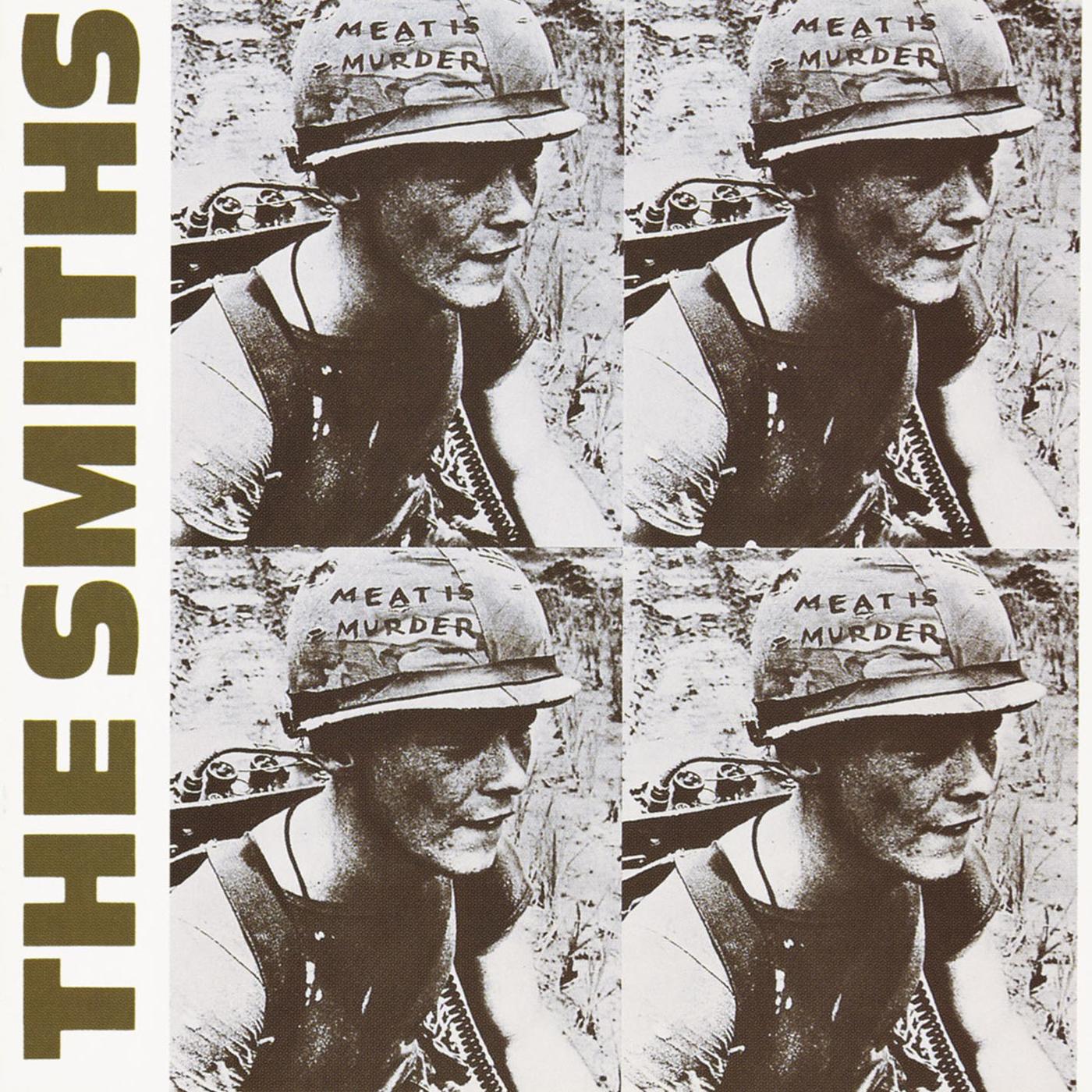

Meat Is Murder (Rough Trade, 1985)

Everything coalesced for The Smiths around the time of their second album. They were tight as a unit, their debut and Hatful Of Hollow had established them as a vital force in British music and now they stepped it all up a gear. That meant honing the fizzing musicality of their previous work at the same time as Johnny Marr expanding his musical vision with folk-tinged diversions and choppy hillbilly riffs. Lyrically, there were leaps forward too – Meat Is Murder was Morrissey’s most politicised work yet, not least in the pro-vegetarianism of its title. Keen to present a united front, Rourke and Joyce became vegetarians during album sessions.

That sense of The Smiths as a gang of defiant outsiders only helped to expand their blossoming reputation – Meat Is Murder became the band’s only Number One album. It also introduced them to engineer Stephen Street, a collaborator who would help them reach new heights on their next record…

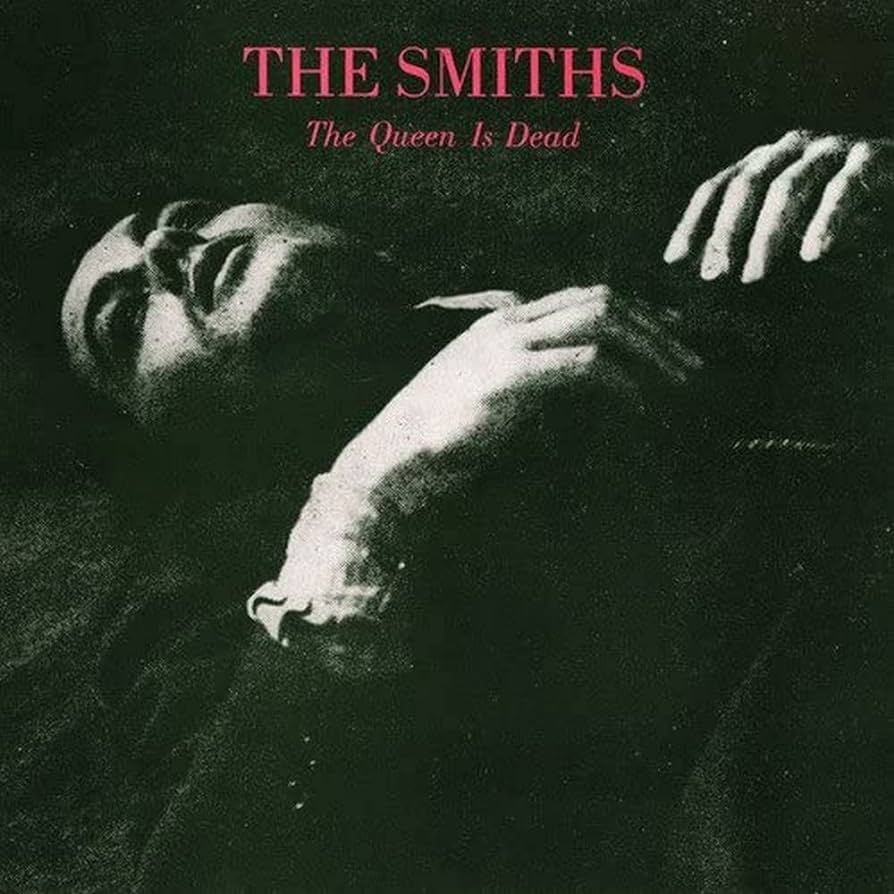

The Queen Is Dead (Rough Trade, 1986)

Both of The Smiths’ first two studio albums had started with tracks that had a certain restraint about them, songs that sounded like they’d been locked in a small room for their own good. With its rolling, loose-limbed drums, turbulent shrieks of guitar and frantic, fluid bass lines, The Queen Is Dead’s opener and title track blew everything wide open. As for the vocals, this was Morrissey at his flounciest and funniest – see the way his voice bottoms out on the word “piano”. Not everyone found him hilarious on The Queen Is Dead, however – Johnny Marr was reportedly aghast when he discovered what Morrissey had done lyrically to Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others, a song the guitarist considered his musical masterpiece. But somehow their ideas beginning to splinter made for their triumph.

One way of looking at The Smiths is that they were a supreme singles band, but The Queen Is Dead is where they did it over a full record. Even before you get to mournful classic There Is A Light That Never Goes Out, there’s a run of jaw-dropping cuts – I Know It’s Over, Cemetry Gates, Bigmouth Strikes Again – that sound nothing like each other but all sound like The Smiths. At this point, they were out there on their own.

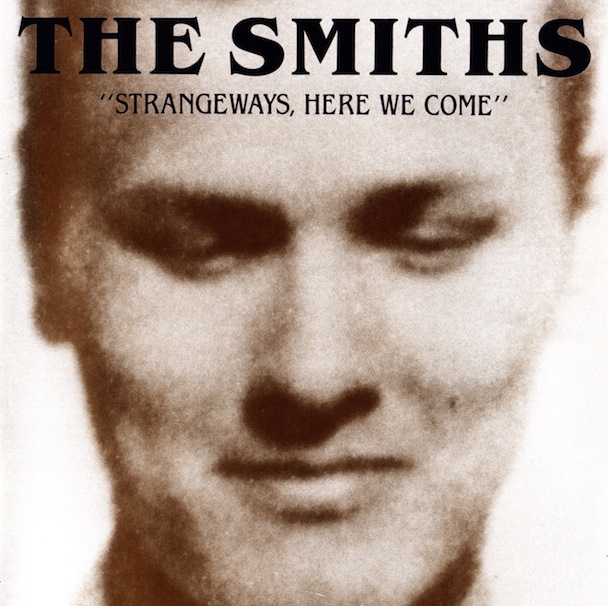

Strangeways, Here We Come (Rough Trade, 1987)

All you need to know about how The Smiths had unravelled in the wake of The Queen Of Dead is that by the time of Strangeways, Here We Come’s release in September, 1987, they had already disbanded several months before. It’s a shame this was the full-stop on The Smiths because it sounds like a gateway to something more experimental and ambitious in scope, taking in haunting piano codas, synthetic strings, ghostly guitar riffs and, on Death Of A Disco Dancer, an outro that weds epic post-rock and boogie-woogie piano. Far from the swaggering host who is saying rude things about your mum on The Queen Is Dead, here Morrissey sounds vulnerable and yearning.

It’s a perfect “let’s start over again” record. Except The Smiths didn’t start over. This was the end. Four studio albums, a smattering of game-changing A-sides and a posthumous live thriller in 1988’s Rank and they were out. The world was never the same again.