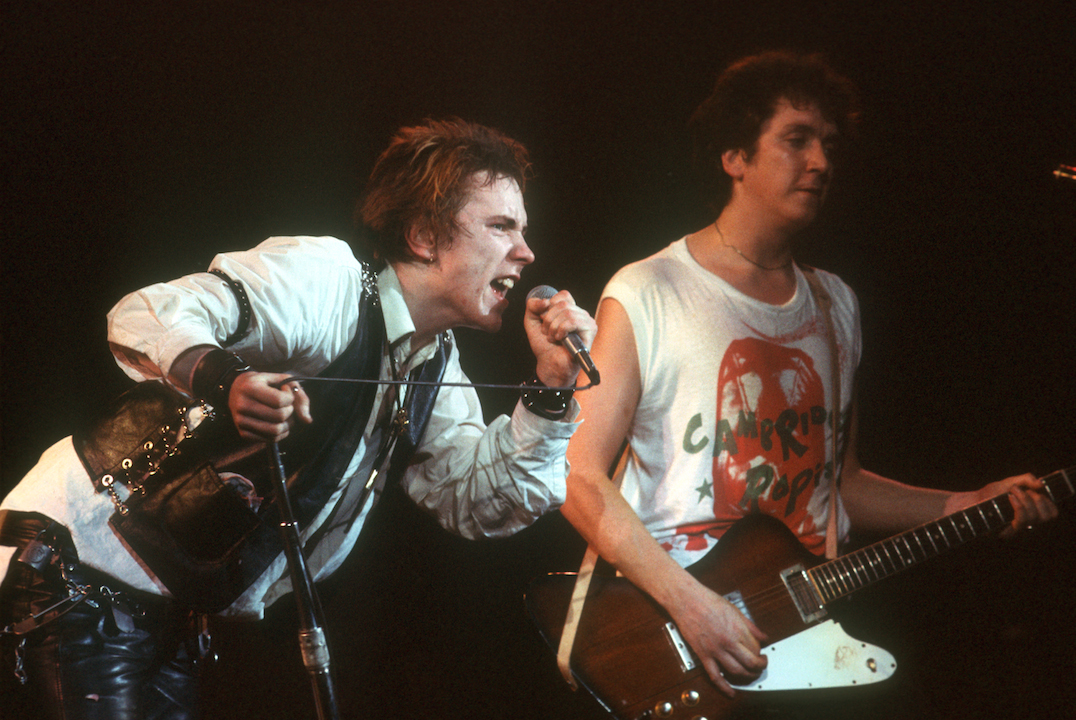

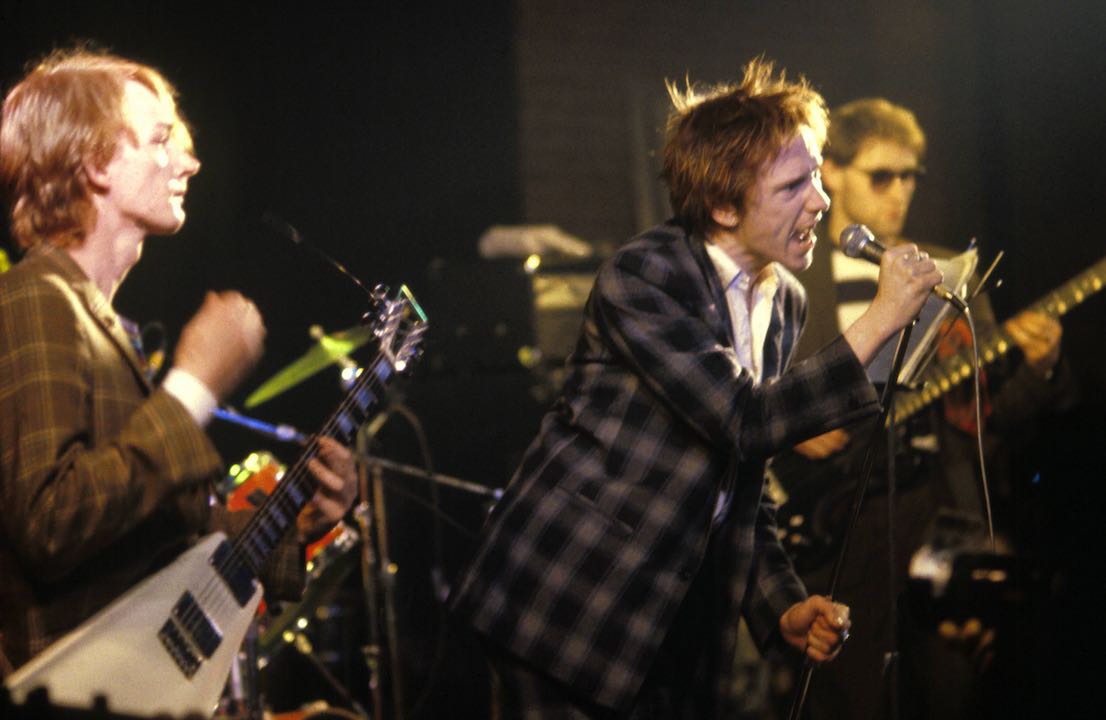

On December 1, 1976, John Lydon – or Rotten, as he was then known – was instantaneously catapulted from metropolitan obscurity to national infamy just for uttering a single, mischievous profanity while appearing on a live, pre-watershed local television show.

Saying “shit” to Bill Grundy, as a 20-year old, defined the subsequent course of John Lydon’s life. Forever ‘Rotten’ in the mainstream consciousness, he has spent the better part of four decades endeavouring to cultivate a more accurate public image than that of a foul-mouthed yob, gobbing nihilism and casually breaking Britain while unapologetically saying the unsayable.

The original Sex Pistols era took up less than 30 surly months of Lydon’s life yet still marks his every move. However much influence various incarnations of Public Image Ltd might exert, there’ll always be countless media hacks queuing up to goad John’s inner Rotten. But not this time. Lydon is in his adoptive home of Los Angeles, where he has lived with his wife, Nora, for more than 20 years. As he boils a kettle to make his morning tea (it whistles shrilly as he pads from couch to kitchen), he’s fully primed to promote the soon-to-come tenth PiL album, the modestly titled What The World Needs Now…

We begin where most Lydon biogs conclude: in the Pistols aftermath. As we wend our way through the late 70s and beyond, we drift back and forth into Lydon’s private psyche. There we find a driven soul, haunted by feelings of guilt since a childhood incident born of a four-year battle with meningitis; a tireless musical evangelist; a struggling stepfather who’s as baffled as the next man by the arcane processes essential to successful parenting; an early-to-bed, early-to-rise home bird, deeply in love with his wife, who laughs easily, adores Led Zeppelin and just happens to have once been Johnny Rotten.

The first thing you did on leaving the Sex Pistols at the beginning of 1978 was make an A&R trip to Jamaica, funded by the Pistols’ label, Virgin. How was that? Did it give you the headspace to formulate your next move, the total reinvention that was Public Image Ltd?

Well, it showed that Virgin had some good intent as a record label towards me. Although at the same time there was shenanigans going on behind the scenes with the others [ex-Pistols guitarist Steve Jones and drummer Paul Cook] putting together a pile of tapes that they called The Professionals. It was presented to me when I came back from Jamaica, actually when I’d just started PiL, as: “Would you just put some voices over it? Put some words to this.” Very annoying. Me, well, I knew about reggae, it’s in my culture, and so any opportunity really for a bit of a holiday. It turned out to be fantastic. I brought [photographer] Dennis Morris and [DJ] Don Letts with me. We had a hoot, and indeed really helped form Front Line, Virgin’s reggae label. It was different times way back then to what it is now.

Were there any specific artists you were instrumental in getting signed to Front Line?

No, I didn’t actually, physically sit down with anyone. I just handed over an enormous list of recommendations. There was a lot of auditioning going on out there, [but] I kept away from that. I was just a magnet, but if anybody asked me about contracts, my clear-cut advice was: don’t do it.

You always had a broad palette of influences: Krautrock, Hawkwind, dub, Van der Graaf Generator, Captain Beefheart, even your parents’ record collection with their Celtic influence was in there somewhere. It wasn’t stuff from Top Of The Pops or even The Old Grey Whistle Test. Where were you finding all this?

Well, that would be there, and you’d see it, and know it was in existence, but for me, from quite an early age, record stores thrilled me, just like book stores did, and libraries. So whatever jobs I had I’d be saving up and rushing out in my spare time or at the weekends, Saturday afternoons usually, and just raid record stores. It was a very good hobby of mine and because I like art too, I was attracted to just the covers of records, many times. Things like [forgotten early 70s prog band] Paladin come to mind there. The man who did that artwork [Roger Dean] also did the Yes albums, but I knew them and friends had them and there was just no need for me to go off into that angle.

Did you have a group of friends that you could swap albums with?

Oh, you would never swap because you know someone would put a thumbprint on your vinyl and that’s how to lose a friend [laughs]. But you would share – you can’t do all this alone, it’s a group thing.

Malcolm McLaren was a New York Dolls groupie-turned-manager when you first met him. Were they your thing as well?

Well, I always assumed that they were following the likes of, say, Kiss. It was a style of glam rock, more closely associated with Kiss, without anything I could hook into culturally. Just talking about being a drag queen from New York didn’t really offer too much exciting imagery to me, so there was the difference there. What I loved about them was the fact that they really, really, really couldn’t play, and that was an enjoyable thing. I discussed this years later with Todd Rundgren. I asked him what was it like recording them, and he said the same thing: the chaos theory in it was good to work with, refreshing.

And they carried it off with such chutzpah.

Yeah, and that’s a lovely thing. Music doesn’t always have to be perfect and well played in order to get its message across. Thinking back to the New York Dolls, I remember loving that line in Babylon: [sings] ‘I got to get away to Babylon, I can’t stay.’ I didn’t realise that Babylon was actually an area in New York City. I thought it was a biblical reference.

Yeah, and with so many connotations to someone coming from a reggae background.

[Laughs] Well yeah, so you can understand my interest in those angles and aspects.

The first incarnation of PiL featured you, bassist Jah Wobble and guitarist Keith Levene. How did the relationship between the three of you develop and ultimately fall apart?

They were mates from before. Keith because he was in The Clash and fell out with them, and Wobble from approved school. So we were off to a flying start. When I started PiL, I wanted it to be a level playing field, but what that really meant was that I was the one paying all the bills and everyone collecting equal profit. Then egos started to creep in and made the whole thing kind of sad. It took a long, long time for me to get a band back into that position of level playing field and egos left at the door, thank you. I mean, I sacrificed my own voice just to get more bass into the grooves, that’s the way I was approaching the studio, which was kind of ahead of the technology at that time.

Ultimately though, there was a clash of egos.

Yeah, you’ll find this with people and, well, they’re your mates and so you endure and you hope that something good will come out of the end of it, but usually it doesn’t. If somebody shows signs of selfishness, it’s a no-no. But that’s alright because they went on to do whatever they went on to, and so for me, no animosity in it.

Before that, the three of you made PiL’s second album, 1979’s Metal Box. If Never Mind The Bollocks was the road map for punk, Metal Box was the road map for post-punk. With the benefit of hindsight, which of the two are you most proud of?

My most important achievement in life was surviving meningitis, and recovering my memory [Lydon contracted spinal meningitis at the age of seven]. All other things really are just cherries on top of a very, very serious death cake, and that’s really the reason for putting out the last book, Anger Is An Energy. It’s very important to me that people understand that I came fully loaded into all of this. I wasn’t discovered under a leaf, desperate to be a pop star. My desperation was to try and get out the fact that I had found myself and I was full and vibrant, and eager to grab the bit. The Pistols I really used songwriting-wise to attack institutions that told us we were hopeless and without point or purpose, kind of woke that cause up, and then moved on to PiL, which was really self-analysis.

PiL’s marriage of that raw self-analysis with your diverse musical influences seemed to work perfectly.

Not at the time, because the press were being so bad-minded towards me. Then again, that’s the story of my life. I always seem to be ahead of the curve.

A nice place to be?

Not really, not all the time, because it makes you feel like you’re on the executioner’s block in an almost permanent way. Then again, it’s a lot healthier than being faced with: “Oh, you’re wonderful,” because then you could fall into laziness. Luckily I’ve never been allowed to do that [laughs]. My most enduring musical restrictions have really been financial. Not having the money to really go to town on things, but I seem to like the cheap and cheerful approach a lot better. I suppose it’s a constant reminder of when I went to Jamaica, of going into the studios and seeing just how little equipment was there yet hearing just how much goodness they could squeak out of it.

You’ve spoken of your enduring feelings of guilt associated with not recognising your parents when you were stricken with meningitis as a child, but it wasn’t your fault.

That doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter…

Do you think that guilt may have been symptomatic of a Catholic education?

No, it’s just how flimsy a personality can be, and how something like that can just take that away, and then you slowly have to crawl your way back. You cannot ever forget that feeling of guilt when it just clicked one day: “Oh my God, this is my mother.” In many ways it’s a gift, it’s an ironic gift, because it makes you stronger, it gives you the will to survive and endure all manner of tragic situations thereafter. I really didn’t have too long a time before my mum died, so it’s short-lived.

Following the trauma of your illness, did you draw closer to your parents?

Not initially, no. No, no, quite the opposite – there was a kind of cold static in-between us. I didn’t know how to express sadness, you see – it’s taken me years to really sit down, and through PiL I learnt to analyse myself and really tear down those walls I had perfected as self-defence.

Did that coincide with a time of normal youthful rebellion? Did a generational divide suddenly exist between yourself and your father?

No, there was never anything like that in my house. Their record collection alone would prove that wrong. They were very open-minded with music, always had been, and that was a very good thing indeed. My dad didn’t understand my love of books, but my mum did. They were very loving. I just didn’t know how to reciprocate that love. I felt I had no skills in it. I had a good four years of my life missing there and I suppose they are very important developmentally, of family bonding, because you can’t go back to pretending you’re seven, not at eleven, so it’s an awful lot of catching up to do and that takes time.

Your mother’s death in 1978 had a profound effect on you, which you worked through, very publicly and at the height of significant police harassment, with the PiL song Death Disco. Not long after, you left your dad and brothers in London when you moved to the States – another wrench…

My dad wasn’t left. That isn’t how we viewed each other at all. We’re dotted all over the planet. My own band at the moment, I mean, Lu [Edmonds, guitar] is in Siberia, Bruce [Smith, drums] is in New York, Scott [Firth, bass] is in Norwich and I’m in LA, but we don’t view each other as being left behind. My dad too, I’ve got to tell you, is a bit of a gyppo and travelling is in his nature. He was always working away from home and so, healthily, that indicated to me that space is not distance.

Around that time, you had helped out your brother Jimmy with his band the 4” Be 2”. In fact, you were on tour with them in Ireland when you were arrested for walking into a policeman’s fist…

It was actually two policemen’s fists [laughs]. I’m really good at that, very clumsy indeed. But good came out of all of these bad situations, because when I got out of jail I went straight back to London and rushed into making [PiL’s third album] The Flowers Of Romance.

The Flowers Of Romance was another bold move. Jah Wobble had left, so you reinvented your sound without bass guitar. Next thing you know, you’d stumbled upon something else, a sound that a lot of drummers, including Phil Collins, took heed of.

Yeah, I had less than a week to work with Martin Atkins, the drummer at the time, because he was off on a tour with Brian Brain, and Keith just wasn’t interested at all, so I had a free run, more or less, and enjoyed every second of it.

The production on a song like Four Enclosed Walls evokes the same sort of paranoia as the Pistols’ Holidays In The Sun. It sounds really claustrophobic, do you know what I mean?

Well, wow… No, I don’t [laughs]. God, it’s only my voice and drums [laughs]. And if I could create that impression just by using drum loops, which is what we had to do, well… I suppose what I was exploring was non-structure inside structure. Four Enclosed Walls has turned out to be quite a forward-thinking song in light of what’s going on in the Middle East at the moment.

Exactly. And it has such a Middle Eastern sound to it as well.

From a Crusader’s point of view.

Shortly after The Flowers Of Romance was released in 1981, you moved to New York. What was the final incident that convinced you that you had to leave London?

As Public Image we found finding gigs in England completely hopeless. We’d very quickly worn out our welcome. There was a hangover from the Pistol days, of fire marshals and local councils having their say, and promoters not trusting any concert that I’d be a part of. So, we had to go to pastures new. We kind of accidentally ended up in New York and, eventually, in Los Angeles [in the early 90s]. It was a long, long process. One thing leads to another in life, a series of small steps.

What was your social life like when you moved to the US? You used to be a really social character when you were in London. Did that carry on in the States?

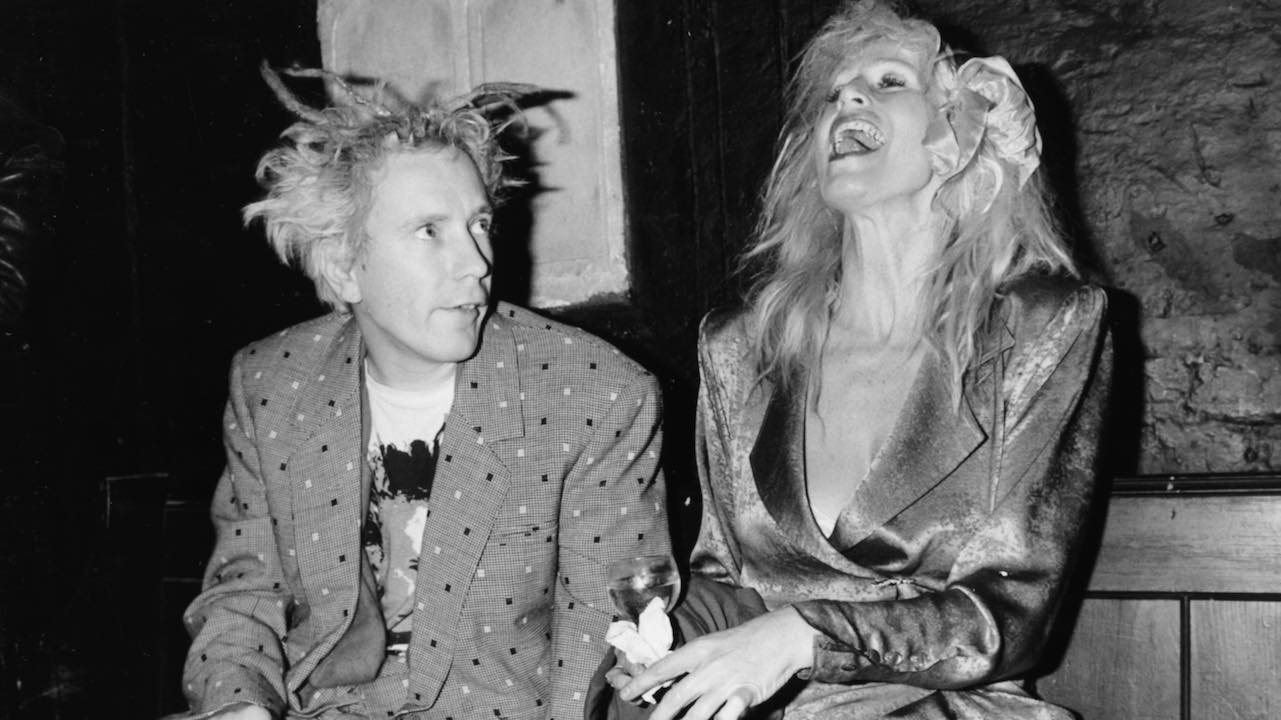

No, I kind of quietened down in New York and I’ve been that way ever since, really. I don’t like to go out to do clubbing or anything like that. I like getting up very early in the morning and I like going to bed early at night, and it’s mostly just me and Nora; very few distractions. And we like it that way where we keep each other company and we don’t tear each other’s heads off. Sometimes all that running around and chatting to endless people, it’s taxing on the brain to remember who half of them are the next day, and I don’t like that. I’m one for very, very deep commitments in my friendships and everything else.

Why has your relationship with Nora remained so strong? I may be wrong, but I expect you can be a little difficult to live with. How have you not driven her to distraction? Does her presence change your behaviour?

Well, that could be said about either of us, but together? No [laughs]. And if other people found us difficult to live with, well, that’s because we shouldn’t be living with them.

You’ve been together for a long time, since London, since punk. She’s the single constant in your life.

Well, what’s that, thirty-five, forty years now? I’m not counting – time flies by when you’re having arguments.

Could you have stood moving to LA without her?

I had to, really, because the business was what drew me here, it was where I needed to be, and we hooked up again properly. I suppose in a weird way I was like the advance guard. I’d also considered, around that time, moving to Germany, but there’d be a language barrier and Stuttgart’s not exactly the centre of the universe, although the idea did appeal to me.

The notion of John Lydon settled in Los Angeles is almost counterintuitive. LA seems like the least likely place you’d ever call home.

Well, it appealed because we played here so much, we became a very well-known California band, and quite a lot of the audience really didn’t know much, or relate to the Sex Pistols background, which was very, very relieving. For many years, I was running two completely different audiences.

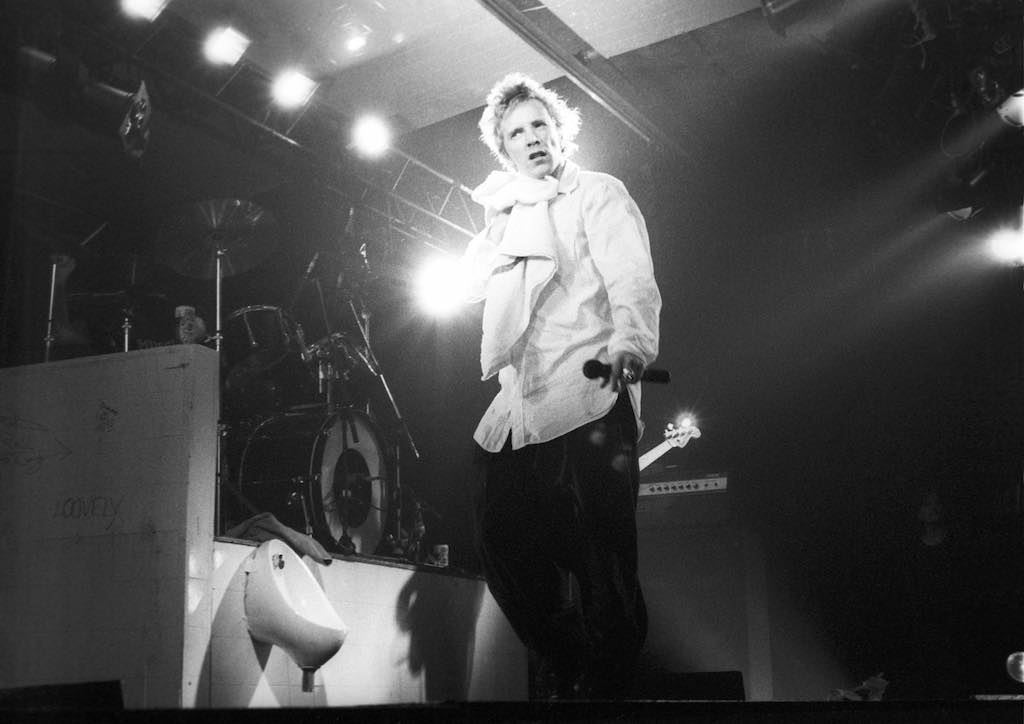

Having seen you play in various PiL and Pistols incarnations over the years, both in the UK and mainland Europe, one thing that strikes me is that people just won’t stop spitting and throwing shit. I’m guessing you don’t get that in the States?

It’s not even like that was ever a part of the Pistols thing. It comes across to me almost like some kind of resentment for whatever it is I do, and well, lo and behold, there it is. Life’s hard, but there are quite a few people out there determined to make it harder for me, and view things in very childish ways. And a lot of this has been media-led, and of course gossip-led too, by people who really should have known better. The alleged adults who were apparently supposed to have looked after me in my early years, mismanagement and the seven deadly sins, and it’s very hard to crawl your way back out of that. That’s not exactly the character I’ve ever portrayed myself as, so I don’t quite know what people expect me to be when they behave like that, other than I feel like turning a hose on them.

The night you brought the Album tour to Brixton springs to mind. People who’d paid to get in were delighting in forcing the band offstage. It’s like that was the show for them, that’s what they’d come for.

The lowest common denominator took over and so the whole ideology of punk developed into something selfish, disastrous and small-minded. Around that time in the mid-eighties they were inches away from seig heil-ing. I can’t endure that. I’m just going to get on with PiL and not bother with it, and hope that the stupidity dies down. It’s taken a long time, but it has. When PiL went out on tour again in the nineties, there was much less of that nonsense and more people remembering punk as it really was. It’s always the imitators that behave in that negative way. I suppose it’s the thrill of trying to out-rotten Johnny Rotten. You know, I’ve created a very, very strong character there that instantly creates resentment [laughs]. I don’t quite know how it happened, but there we go.

You don’t seem to have been altered at all by your environment. Even after 35 years in LA you still show no outward signs of having become intrinsically Californian. But what about Finsbury Park? Do you still feel at home there?

No, I don’t suppose I’ve ever felt like I truly, totally belong to any lump of soil. I’m fairly transient and I’m not easily affected by my surroundings to the point where I feel I need to imitate the locals in order to fit in. You know, you take me or you leave me – either way, I’m just going to continue to be what I am. The main attraction for coming to California was the all-year-round similar weather. In fact, we don’t have weather here – it’s consistent and that’s very, very good for my physical health. Meningitis left me with many, many problems. All physical, I mean. I just can’t bear living in England for another November. It’s guaranteed pneumonia.

In 1983, after you moved to the US, PiL had their biggest hit with the single This Is Not A Love Song.

Yeah, eventually it was, in a very roundabout way. Virgin didn’t want to release it at first and that forced me into the position of releasing it somewhat erroneously on a German label and in Japan, and it took off in those two markets – amazingly, frighteningly, because it immediately brought to attention that, “Oh dear, I might have a contract problem here.” And Virgin could have played a bad ball here, but they had in mind, “Oh no, look, we’ve told him he doesn’t stand a chance of making any money with his silly new music, and here he is doing exactly that. We might as well go with the flow for a bit.” That’s a simplistic way of putting it, but that’s basically what happened. And then, of course, they jumped down my throat on the next bunch of stuff I’d be putting up, telling me I wasn’t commercial enough

The fact that no one knew what you were going to do next had become your selling point. As if to prove that point, you went off to do 1984’s World Destruction with the pioneering hip-hop DJ Afrika Bambaataa.

Bambaataa played a lovely, oddball collection of music at his gigs and that drew me in. We found we knew the same people that were hanging around the dance club scene in New York. That’s where I met [avant garde musician and producer] Bill Laswell.

Then there was another career tangent with 1986’s technically faultless, comparatively heavy Album, which Bill Laswell produced. It featured an incarnation of PiL that included Steve Vai, Ginger Baker, Tony Williams, Ryuichi Sakamoto and Bernie Worrell. Was that line-up contrived at Laswell’s suggestion?

No, I had a very young band from California at the time, very young kids, but when I took them to New York to make Album with Bill, they panicked and shit themselves in the studio. They couldn’t handle the pressure, so I had to just knock that on the head and get in anyone who was available as quickly as possible. It was quite literally on the phone: “Look, can you do this? Can you do that?” The songs were already there, they had to just come in and give it a quick listen and see where we could go from there on in. Because [PiL’s label] Elektra were on our case, and so we released the album without mentioning anyone who was on it, and it went straight in at No.80 in the American charts. And that same week, Mr Krasnow, the head of Elektra, asked to have a meeting with me and told me he’d have to let me go. The plan was that they were going to invest all their money in Metallica, and they couldn’t really see a future for my kind of music. And so, there we go, we parted our ways. It was only after the event that they found out who was actually on the album they’d dismissed. The irony is not lost on me.

And how ironic that the NME had previously reported that Ginger Baker had joined Public Image Ltd as an April Fool’s Day news story, only for him to then appear on Album.

I know, the joke backfired on even them [laughs]. Working with Ginger was fantastic – what a nutter. Wow… free-range talent that one.

He’s almost more Johnny Rotten than Johnny Rotten.

Similar backgrounds you see, and so there was a lot of good point and purpose to it. I could understand his rage very, very easily. Steve Vai was a terrific bloke, and terrific to work with. He’d never attempted in his whole life any kind of rhythm guitar up until working on that record, and he wasn’t quite sure that he’d be capable of doing it, or achieving it, so what we did was, we all just went out and got drunk on saké and came back in, and lo and behold, there it is. Once the pressure’s off, the stuff starts to flow.

The biggest hit from Album was Rise. Only an Irishman could have come up with that record. It’s very Celtic in both its sound and sentiment.

Yeah, with possibly a bit of Zulu thrown in for good measure [laughs]. I was listening to an awful lot of African music at the time. A lot of that was to do with Ginger, of course, because he’d come with the African nations wrapped around him. So yeah, you’re right, the song is an Irishman’s song but it shape-shifted into many other things besides. The song came first and the lads who came on board brought in other aspects, and so we played around with that. It was the first time ever that I was really in a proper big-time studio and treated with some kind of respect, where I wasn’t told, you know, “Don’t sit there unless you put a plastic bag down.”

I remember waiting in the bar for you to come on during the Album tour, hearing Led Zeppelin’s Kashmir coming over the PA, and thinking the DJ was having some kind of breakdown, but it turned out to be the first song in PiL’s set. Quite an audacious move.

Yeah, I know. I was supposed to run on and do the Robert Plant bit, but no, I can’t [laughs]. I mean, we’d rehearsed it, but it never, ever felt right to [do it]. I thought I’d be standing in someone else’s shoes at that point, but it was a good homage to a band that we do love. Although, yes, I’ve never mentioned Zeppelin very much, Physical Graffiti is one of my favourite albums. The sheer terror and ferocity of it… beautiful landscaping.

And there’s a very similar Middle Eastern influence to that found in Four Enclosed Walls at the very heart of Kashmir.

Even though none of us think about it. Come on, the boys came from Birmingham – there’s curry houses all over the place, mate [laughs]. You know what I mean? It’s your surroundings.

You put PiL on indefinite hiatus in 1993, following a couple of water-treading albums. But you followed that with Open Up, an inspired 1995 collaboration with techno duo Leftfield. How did that come about?

I knew Neil [Barnes, Leftfield founder] from working in the play centres, which was the job I had before the Sex Pistols. Where you’d look after children whose parents worked late after school, and in with that lot were, of course, some problem kids too, who needed to be kept off the streets and so you provide some kind of attention for them. I loved that job – set me up lovely for the Pistols, by the way – but Neil did similar work, so that was the connection through a friend called John Gray.

Years later, one thing led to another when they were starting with Leftfield and I always got on, I thought, very well with Paul [Daley, Leftfield co-founder]. The only trouble was that the pair of them didn’t seem to get on very well with each other, which leaves you thinking, “Oh my God, all bands seem to be like this.” It took a few years to actually get it into the studio because their original demo idea was, for me, too slow. Then someone had the bright spark of saying, “Look, we’ll just speed it up!” So I heard that, ran straight in and made it up on the spot. We did it very, very quickly, in less than one evening. It was great fun to do, and then, of course, when it was released six months later, I was accused in America of profiteering on the fires that were burning down the Hollywood Hills because of the line ‘Burn Hollywood, Burn.’

My God, you can’t win, can you?

You can’t win [laughs]. Hello, there’s a journalist here trying to tear me a new arsehole and, for God’s sake, just get it right. I mean, even you clowns must know that it takes six months before you get a record released. But there we have it.

It’s interesting you saying how your experience with the play centres helped you with working with the Pistols.

Yeah, problem kids [laughs].

Do you think your relationship with Steve, Paul and Glen was broken from the beginning? After Malcolm recruited you, they didn’t even turn up for your first rehearsal.

Yeah, it was a very, very bad, ugly thing to do.

Do you think they might have preferred Malcolm to have found them a Rod Stewart type so they could have simply become a new version of The Faces?

Listen, I’ve got to tell you that as people, outside of making records or rehearsing or anything like that, I really like these fellas, and so that’s what drew me back in. One consistent factor of the Pistols that made it work was that Paul Cook is so level-headed and he’s the voice or reason when we’re all yelling and trying to tear each other apart, and that kind of works. He was the maypole we danced around, and that’s why to me he will always be one of the best drummers I’ve ever heard in my whole life. Not only has he got perfect timing, he keeps it nice and simple, but he has a personality you can trust.

Yeah, that’s important in a drummer.

Bloody hell, yeah. And here I am, having worked with the other ultimate extremes in life and I can tell you there’s good and bad in everything. Whatever the situation is, make the best of it. There’s no time for wallowing in self-pity. You have to get into it, because you’re here for this purpose, and for me, this is the only thing I’ve found in my whole life that I was actually made for. Illnesses and all the horrible situations in my life fully well-rounded me to be able to do this. Songwriting is my thing. I’ve found myself, and I’m not going to throw that gift away by making commercial crap. Even though the term ‘sell-out’ has been thrown at me since day one [laughs]. And, my God, people accusing the Sex Pistols of being a boy band? Well, I look back now and go, “Yeah, we were a boy band… unlike any other.”

What compelled you to take complete control with your first solo album, 1997’s Psycho’s Path, where you played all the instruments, as well as self-producing it?

Not all of it, just bits and pieces. There’s always someone skilful working in the background. I like to put myself in these high-risk situations. When I feel that amount of energy and tension building in me, there’s only one place to go, and that’s straight into the studio. I built a studio in LA so I can just go in and mess about all day long. I far prefer working with other people. I like to be sprung off, get other ideas outside of my own, just as much, probably more so, to avoid the conceit of actually studying the violin, or the piano, or the saxophone. All my hard work really goes into the vocal side. I’m trying to drag things out of my personality that maybe I’d rather keep buried, but if you’re going to write a good book, it has to be an honest book. If you’re going to make a good record, it has to be an honest record, and this is what you have to do.

It’s the process of dealing with a lot of stuff, I guess, because you can’t voice it in any other way really.

No you can’t, and there’s no self-pity in it, because this is something my mum and dad never would have allowed. I’m always aware of that. They’re still in there, lurking about inside my head, giving me a good slap if I go on to a wallow.

Following Psycho’s Path, you tried a lot of new stuff away from music, including dipping your toes into the world of reality TV with I’m A Celebrity… Get Me Out Of Here. Were you disillusioned with music as a whole or just the business of making music?

I found myself stranded and abandoned, and at the same time hugely in debt. If I tried to form any kind of band there would be outstanding bills to be paid, so I needed to make money elsewhere for a while. I was financially crippled by the labels and that was very punishing. I couldn’t even get a new label because I was still connected with debts from the old ones. So any new adventure that crossed my path, I thought, “Ha, I can do that.”

And you had a right laugh with it, obviously.

Yeah, only because I was able to pick and choose. I had a very, very good time with eYada – it was an internet radio broadcaster. I’d broadcast live from my house every weekend for four hours, and that was a great, great time, because the people I wanted to talk to weren’t rock stars, they were American intellectuals, philosophers and politicians, and I really, really enjoyed that, and I did intersperse that with all manner of oddball bits of music I’d find. I continuously raided record stores because music’s for sharing. So are ideas, and if you can combine the two together, wow.

Interestingly, while Never Mind The Bollocks and Metal Box shaped a lot of people’s musical future, the radio show you presented on Capital Radio in 1977 with Tommy Vance was of equal influence on that generation. Pistols fans who tuned in for a lesson in punk were presented with Krautrock, dub and various esoteric sounds that had never been broadcast before.

Well, it’s what I like, it’s what I am, it’s part of what’s been the making of me, and why on earth would I want to deny that and pretend to be something I’m not? Here’s where the rows with the management started.

Malcolm McLaren really hated you doing that radio show, didn’t he?

Yeah, absolutely. Thought that was ruining the image. You cheeky bastard! What image? I am the image. I write the fucking songs, don’t I? [Laughs] I’m the one what had to stand up there and endure. While Malcolm’s swigging Bloody Marys, I’m the one what had to stand there behind the microphone and take whatever comes, so anybody who had the audacity to tell me what my image was or wasn’t, it wasn’t going to go down too well.

And you had to be the front, and suffer the consequences, for all his often-ruinous ideas.

Yeah, and all his ideas were reverse engineering.

And he wasn’t terribly supportive. When he sent you out on tour through the ultra-conservative southern states of America, he was notable by his absence.

Well, that was a good idea because we found it verydifficult to get gigs anywhere as the Pistols, and to tour the south just seemed extremely audacious, and proved to be a very, very wise move. Go straight into the heart of the alleged enemy and, Ithink, you’ll find that they’reyourtotal friends.

You’ve done the Pistols reunion thing twice. Is that permanently finished with now?

I wouldn’t call it a reunion; I don’t like that word. For us it was a make up or break up, and we made up and now we’ve broken up. We’ve got it out of our systems; now we can get back to being friends. It’s very important that be understood – I value them all as human beings far more than I do as me in a band with them.

And you really don’t want to become the Rolling Stones, doyou?

No. I don’t, no. Forever trotting out the same monotony? No. No, no. I can truly, honestly say I’ve never done this for the money. I think the evidence is overwhelming [laughs]. I laugh at it myself because if I go back and I look at my life, Ithink, “My God, you know, are you a bit silly? Youcould have tea-cosied there for a bit.” Nope, can’t have it. There’s just something in me that just says, “No, I won’t wake up and feel good about myself.” So there it goes. So integrity is the word Ihover around, hoping that that is indeed what it is, because there’s every chance, if you fully believe in integrity, that that’s not what it is at all. This is the trouble with over-thinking yourself. You know, I mean it when I say I’m my own worst enemy, so no matter what bad can ever be said about me, it ain’t nothing that I’ve not already considered.

Surely you can’t lie in bed awake all night worrying if you’ve got integrity.

Well, I can’t lie to myself. It took me four years to remember who I was and I’m not going to let that one slip, never, ever again.

Lu Edmonds and Bruce Smith have been members of PiL since the 80s. Why do you think you’ve been able towork so well together for so long?

Because Lu’s a bit nuts. I suppose he’s a bit like myself. He could have taken the easy road and just been a punk guitarist – of some good repute too, let it be said – but he got bored with that. His ideology is to explore every sound and find good in everything, and that’s very similar to me. When on stage, we’ll put in leading notes or drop hints and take the songs into other areas, and Bruce is very, very in tune with us in that respect, and Scott most definitely. After all these years we’re finally getting to where we want to be, so the pressure’s off – we don’t record just for the sake of it, and we don’t have to make commercial crap. We do what we do, we’re now fully independent and no one waves a finger over us saying, “No, no, no,” or“I’llcancel the cheque.”

Double Trouble, the lead single from the new PiL album, sounds incredibly contemporary. Put it next tothe Sleaford Mods and it sounds fresh as a daisy.

Yeah? I would have thought that was one of my more old-fashioned styles [laughs]. Well, there you go. You know, we do what we do. The sound and the attitude of it are completely appropriate to the subject matter, and that’s what you end up with.

And very appropriate to the time we’re living in.

Well, yes – if you’ve got a broken toilet, fix it. I don’t think I could get more political than that.

One of the worst things that’s happened to you in recent years was the death of Ari Up, the daughter of your wife Nora and former singer of The Slits, in 2010.

The death of Ari absolutely shattered Nora, so we’ve had a lot to endure. But the night before Ari died, we went to visit her in the hospital. I’d been refusing to go, because I thought it’s just going to be another row about not raising her kids properly [Lydon and Nora were closely involved in the upbringing of Ari’s three sons], but we got on really well and sang Four Enclosed Walls. The hospital staff let her scream her head off and she fell asleep happy and just stayed asleep. That was a lovely way for us to part. The only one who sang in tune in the whole thing was Nora [laughs].

I’m guessing Ari’s children must feel a lot like your own kids by now.

To me, yes, but they’re very, very difficult now. Stepdad is a very difficult position to find yourself in. Sometimes, no matter what good you think you’re doing, it’s always perceived as somehow wrong, and it’s very, very difficult.

Do you sometimes look at the children and think how different their upbringing has been to your own in Finsbury Park?

We might have made it too easy for the twins. We tended to spoil them. Can’t help it. I’ve always had kids wrapped around me. I’m one of those people that doesn’t mind children making noise on an aeroplane – it’s not irritating to me at all.

What’s your attitude to mortality? You made your feelings clear on Religion from PiL’s first album, but is there a small part of you that retains any iota of faith, and the afterlife that goes with it?

Afterlife? Well, that’s presuming there is such a thing as death [laughs]. I have no answer to that, no man-made religion is supplying me with anything like enough information. Out of the dust we come, back to the dust we go. It seems to be the rightful thing to do.

And there we leave him, even more buoyant than we found him: open, optimistic, gleefully self-deprecating, as far from the combative tabloid-created Rotten as it’s humanly possible to get.

“May the roads rise and your enemies always be behind you,” offers punk’s erstwhile firebrand by way of parting gesture. “May they scatter, flatter, batter and shatter,” he continues, cooling ever further toward a state that can only reasonably be described as contentment, before concluding with a forthright, exclamatory “Peace!”

Who knew the day would ever come when John Lydon would say it, let alone find it.