“I’ve been doing this job for over half a century and all of a sudden I was unemployed,” says Al Stewart of the effects of recent events. “But I rather liked having a year off because I’ve worked in a straight line since I was 19.”

On his 1973 autobiographical song Post World War Two Blues, Stewart sang that this all began when he travelled to London in 1965, ‘With a corduroy jacket and a head full of dreams.’ He soon established himself as a singer-songwriter in the capital’s folk scene. In the 70s, together with artists such Roy Harper, Ralph McTell, Sandy Denny, Richard Thompson and Michael Chapman, he helped create a golden age of progressive folk rock, using imaginative arrangements and expanded structures. Stewart developed a signature style of writing with lyrics inspired by literature and history. “I wanted an historical folk rock record and the only way I would get my hands on one was if I did it myself,” he explains.

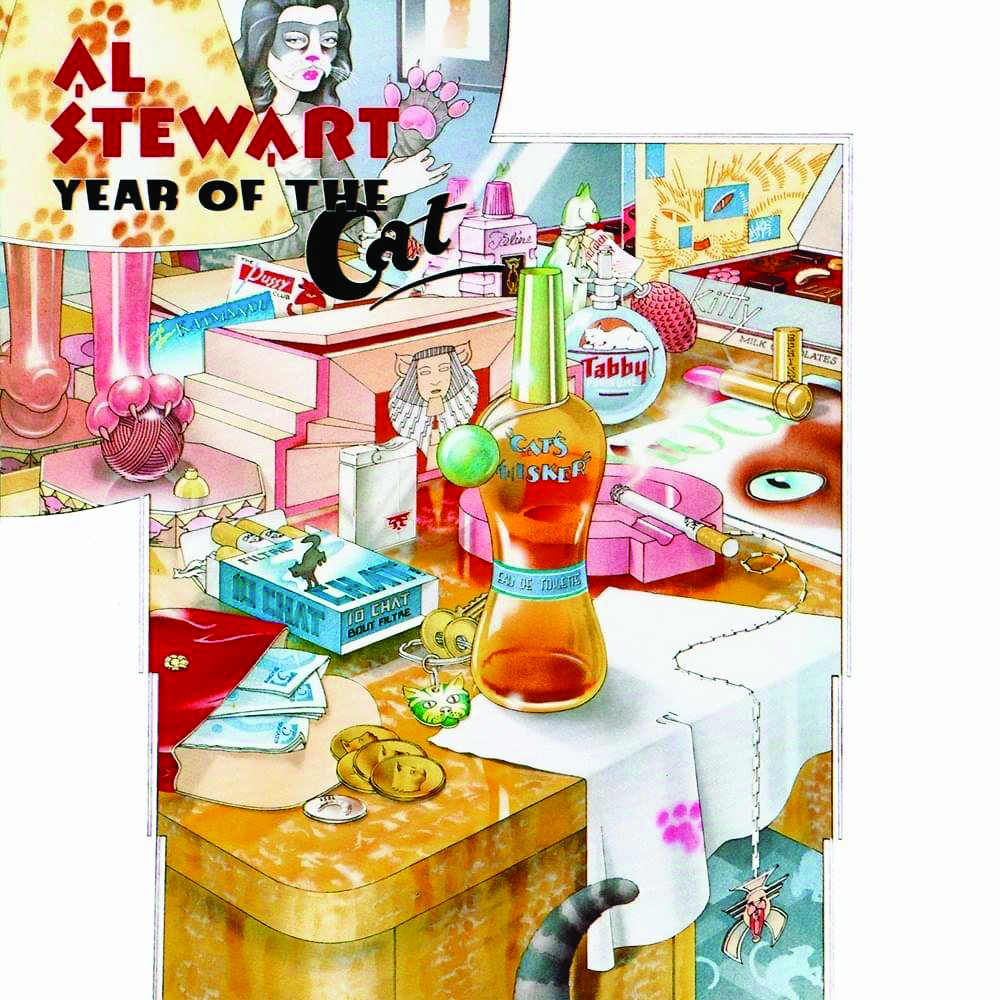

In the mid-70s he achieved considerable commercial success with Modern Times, which reached No.30 in the US Billboard charts. It was followed by the smoothly polished Year Of The Cat, which got to No.38 in the UK but No.5 in the US, with title track peaking at No.7 in the singles charts.

Stewart’s albums have continued to gain critical praise. And if, as he hopes, “normal service is resumed”, he has a UK tour pencilled in for October this year in which he hopes to play old favourites and highlight some new material.

Although you were born in Glasgow, you grew up in Bournemouth. What was the music scene like there?

After I left school I spent two years playing in bands. Everything was modelled on The Beatles, The Kinks, The Who, and The Hollies. By 1965 I realised that Bournemouth wasn’t the way to make progress and sign record deals; you had to go to London to do it. So I arrived as a 19-year-old would-be rock’n’roller.

How did you get on in London?

I auditioned for The Paramounts, who turned into Procol Harum, and The Outlaws, who had just lost their guitar player, Ritchie Blackmore. But although I was a passable guitar player in Bournemouth, London was a different thing. I thought if I worked really, really hard I could maybe become the 3,475th best guitar player in the UK.

When I arrived in London, a folk club called Les Cousins had just opened in Soho. I got to know the owner and he said, “Do you want to be the compère?” So I would do the midnight to 6am slot. I also got a job singing at Bunjies Coffee House every Friday. I just walked in with a guitar one day and the owner said, “Are you a folk singer?” Of course I wasn’t, but I said I was because I smelled a gig. I’d learned some Bob Dylan songs and everyone seemed to like them.

Then I saw Bert Jansch and I’d never seen anyone play a guitar like that. He sounded like three guitar players and he was snapping the strings and using his fingers when we all played with a pick. That was a revelation.

There was a social worker in the East End who let me stay in her apartment for free. One day she said, “Look, there’s this American singer who stays here every time he comes to London and you’re in his room. There’s a little room next door you can use while he’s here.” This turned out to be Paul Simon. So I got a crash course in learning how to write songs basically by just putting my ear to the wall.

Paul had just written Richard Cory and it was one of the best things I’d heard in my life. I think the next day he finished Homeward Bound and I said, “No, no, Richard Cory is the hit.” That began a long period of my complete inability to recognise anything commercial.

So by the end of 1965, due to Bob Dylan, Bert Jansch and Paul Simon, and my inability to play the electric guitar very well, I’d been transformed, somewhat reluctantly, from an aspiring rock’n’roller into a folkie and I began writing my own songs.

Your 1967 debut album, Bed Sitter Images, evokes a strong feeling of what it was like to be young in the 60s, but its themes also seem applicable today.

People don’t change very much. But that record was all over the place. The title track is a straight-ahead folk-rock tune, then you’ve got Cleave To Me, which is cod-Shakespeare, and Beleeka Doodle Day, which is a kind of Procol Harum knock-off. The only reason I made it with an orchestra is because Judy Collins had made In My Life with an orchestra and, at that moment, folkies with orchestras were thought of as being something that people would like.

Karl Dallas wrote of the album in Melody Maker in 1967: “Al Stewart leaves the ranks of folk for the pop scene.” It appeared that your status as a folk artist was in peril as soon as you started recording.

Well, was I ever a folkie? I mean, I always thought I was playing folk rock, especially when you look at Love Chronicles – that had Fairport Convention and Jimmy Page on it. I heard Martin Carthy and The Watersons, and all these people and I thought they were really good, but I don’t think that I was ever doing that.

Do you think your main overlap with folk was that your songs had strong narrative threads?

In bands you played and people danced but no one was really listening. But if you played in a folk club they listened to every word. You could hear a pin drop. As I went along, I became more and more wordy and you really can’t sing some of those early songs in rock clubs because it just doesn’t work. But when Love Chronicles came out [in 1969], that one did pretty well and I got promoted to the college circuit. I really liked it and for a couple of years I was a fixture.

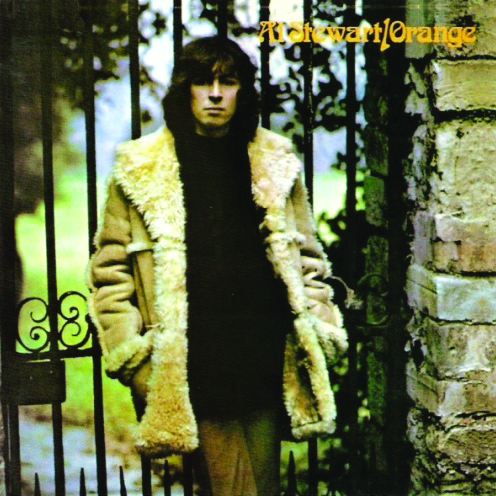

On Orange [1972] you started to explore historical themes. Rick Wakeman played on that album and the progressive rock scene was going on around you. How much of an overlap did you have with that scene?

I knew the Crimsons as they came from Bournemouth. I grew up down the street from Robert Fripp. We used to take the bus together when he was 15 and I actually took 10 guitar lessons from him. He taught me all these jazz chords that I never used again in my life [laughs]. Someone asked him in an interview once, “You’ve had all these students – did any of them become successful?” And Fripp thought and said, “Yes, one. And he did it by ignoring everything I ever tried to teach him.” I guess that was me!

Rick Wakeman was a wonderful person to work with, as he told jokes through the entire session. I’m in a booth trying to do a vocal and the band are set up and every time I hear “one-two-three-four”, I hear a voice saying, “’Ere, Al, have you heard the one about…” I met a lot of people who you might call prog.

It seemed that you shared the progressive mindset of some folk artists who were stretching out and becoming more musically ambitious, like Roy Harper on Stormcock, for example.

Songs did start getting longer. I’m partly responsible for that as Love Chronicles was 18 minutes long, and there was also Nostradamus and Roads To Moscow. The Incredible String Band, and Fairport Convention would also do extended versions. We’d grown up with the idea that a single was two and a half minutes long and I said to myself, “Why shouldn’t there be another way?” On the other side of the coin I wrote a song [with a vocal section] that was 15 seconds long called A Small Fruit Song. There were amazing things happening in the English folk scene in the 70s. Everybody was trying to outdo each other, and looking back on it I think it all still sounds good.

When you were interviewed in Beat Instrumental in 1972 you admitted an ambition to become an MP. What’s the story behind that?

Yes, I had a friend at the time who had told me that he would be prime minister and I thought that I might as well go along for the ride because it might be fun. I was talked out of it very quickly. I was beginning to achieve some success as a folk rock singer and that seemed more interesting. And I had no particular party that I supported, so I don’t know what I would have run as!

You have said that your 1973 album, Past, Present & Future, was pivotal in the development of your songwriting. Why was it so important to you?

I was trying to come out of a manic depression after a terrible end to a love affair and I never wanted to write another love song. At the time I would sit up all night reading history and I was burrowing through Solzhenitsyn when I was probably supposed to be at the Speakeasy chasing groupies. I’ve always loved movies and documentaries and always loved music. I thought, “What if I put them all in a bucket and stirred?” So all of a sudden I had an album full of historical songs.

But I thought this had no commercial application whatsoever. Roads To Moscow is about the Russian Front in World War Two for Chrissakes, and it’s eight minutes long: this is not what gets played on the radio. And the record came out and it outsold the first four put together. In America it only got airplay in a couple of cities: Philadelphia, and Seattle, where it became an anthem. In 1995, KCOK, the top FM station in Seattle, did a listeners’ poll of the top 200 songs of all time and predictably Layla and Stairway To Heaven were one and two, but Roads To Moscow was number three.

Alan Parsons produced and did arrangements on a number of your albums in the 70s. How did you get to work with him?

When I first met him, he was a big person for going out to dinner with nice wine, which is something I also excel at. We were in a restaurant having dinner and probably talking about wine and food, and halfway through the conversation, I said, “Look, I’m making a new album for CBS, would you be interested in producing it?” And he said, “Oh… alright.” And then we went on talking about wine. It was literally that easy. So we went into the studio [in 1974] and made Modern Times.

My manager, Luke O’Reilly, had been a disc jockey on a radio station called WMMR in Philadelphia. He said, “Look, we have to break America. We have got to do a tour but we’re [really] going there so we you can go to every single radio station and introduce ourselves.” And the result of all that was that at the end of the tour Modern Times had got into the Top 40. The next album was Year Of The Cat and as soon as that came out all the radio stations that I’d made friends with played it and

it started stomping its way up the charts.

You’ve said about Year Of The Cat [1976] that you “finally got the formula exactly right”. What was that formula?

Some key elements were missing. I don’t think I’d appreciated how important a producer was in making the thing sonically great and, of course, Parsons could do that. Over the years I’ve worked with some great guitar players and my favourite was Tim Renwick from Sutherland Brothers & Quiver, who was a very melodic player. That was exactly what I wanted and he was all over Modern Times as well. We borrowed a couple of musicians from a band that Alan had just had a No.1 hit with called Cockney Rebel: Stuart Elliot on drums and George Ford on bass. So we had a great rhythm section, a great guitar player and a great producer. And then we brought in Andrew Powell to do some wonderful string arrangements and Alan brought in this sax player, Phil Kenzie. So we had a team. And of course I had Luke who knew how to sell it. The only reason that record wouldn’t have been a hit would have been if I’d screwed up the songwriting [laughs].

On 24 Carrots [1980] you use five different drummers and a total of 17 musicians. How did you go about choosing who played on the album?

It was a case of who was around. Jeff Porcaro [from Toto] is on one track and he’s an incredibly good drummer. I remember being in the booth and just watching him, not listening to the rest of the band, because he’s so extraordinary. When he finished he stood up as if he was going to take a round of applause, which he deserved, but I’d never seen a session drummer do that.

LA is like that, and people just wander in. We had David Pack from Ambrosia in one day and he sang on If It Doesn’t Come Naturally, Leave It [on Year Of The Cat]. And Tori Amos came into one session and I asked her to sing on it [she sings backing vocals on the title track and Red Toupée on 1988’s Last Days Of The Century].

You’ve said that you knew the commercial success you achieved with Year Of The Cat and Time Passages couldn’t last forever. But how did you adjust when it all calmed down?

All of a sudden we were playing to 3,000 people, but I very quickly realised that the 300- 500 who had been there to hear Roads To Moscow or Nostradamus was the core audience and the rest were tourists who had only really come to hear Year Of The Cat. Time Passages is like Year Of The Cat Part 2 and I thought those people are going to go unless I keep doing it over and over again.

Clive Davis [then president of Columbia] said specifically that he wanted a mid-tempo ballad that could be played on the radio with a saxophone on it. So I wrote a song called Song On The Radio. This is me making fun of Clive, I hate to say it [laughs]. It was a Top 30 hit in America, but you can tell that this was not the music that I wanted to play for the rest of my life. After that I edged my way back into playing rooms where people who like folk rock were actually paying attention.

Have you written songs inspired by any recent current affairs?

No, I like at least 30 or 40 years to go by as very often what you perceive to be happening now isn’t. For example, when I was growing up, Eisenhower was America’s president and he was widely viewed as past it and a bit of a dull person who didn’t really know about anything. Of course this is completely wrong, but it took the declassification of Eisenhower’s papers to let us know what he’d got up to. So it’s best to have the facts before you start writing about it otherwise you end up with something like [Barry McGuire’s] Eve Of Destruction.

But in 1984 you wrote Russians And Americans. How was that received in the US?

I don’t really know. It sold to the core audience but it was not a commercial record. I love some of the lines. I rewrote Len Barry’s 1-2-3 into a political diatribe about building empires: ‘Primitive country/Rich in minerals/You pay them with beads/Tip the generals/It’s easy, like taking candy from a baby…’ Clive Davis’ only comment – because I don’t think he listened to a word – was, “Oh, why did you speed it up?” [Laughs].

On your most recent studio albums, A Beach Full Of Shells from 2005 and 2008’s Sparks Of Ancient Light, you continue to explore historical themes. How much research do you do for songs?

I don’t think I’ve ever researched a song and then written it. I just file [information] away in the back of my mind and the song might come 10, 20, 30 years later.

One way to write a song, which is foolproof – to me anyway – is just to open an atlas at random. The Loneliest Place On The Map is probably my favourite track off Sparks Of Ancient Light. I opened the atlas and I was looking at Antarctica, and there is [a group of] islands at around the 50th parallel called Kerguelen, a remote French naval station. It’s basically as far as you can get away from everything.

How has your way of writing songs changed over the years?

I don’t think I’ve changed at all. Modern Times, Year Of The Cat and Time Passages, for example, I not only wrote the music first, I recorded it before I had any words, which is a very unusual way of going about things. I have a habit of writing three or four sets of lyrics for the backing tracks, or if it has three or four verses I might write 12. I write lots of words on different subjects. Year Of The Cat was originally called Foot Of The Stage and it was about the English comedian Tony Hancock. The American record company said, “We’ve never heard of Tony Hancock”, so I rewrote it a few times. I think there have been occasions in the past where I have chosen the wrong ones [laughs]. I’ve gone back and looked at the exercise book and thought, “That’s a much better verse than the one I used. What was I thinking?”

This article originally appeared in issue 119 of Prog Magazine.