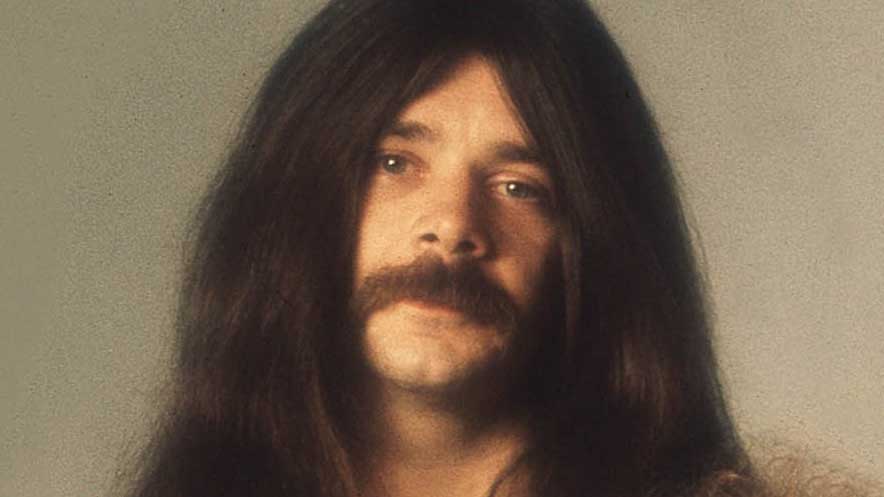

Black Oak Arkansas founder and guitarist Rickie Lee Reynolds has died at the age of 72.

The news was broken by Reynolds' daughter Amber Lee in a post on Facebook, who revealed that the guitarist had suffered a cardiac arrest in hospital, and that medical staff had been unable to revive him. She wrote, "We are all heartbroken by this massive loss, and the whole world feels colder and more empty without his presence among us.

"Please take a moment of silence today to remember all of the love he gave to the world, and take some time to give back some of those wonderful feelings that he gave us all in our times of need. Share his greatness with another today, and help make the world a better place, just as he did. Let's shine his light upon all around us. Look at something beautiful today and truly appreciate it deeply in your soul."

Lee's post came less than a week after she wrote that Reynolds had been admitted to hospital and had been battling COVID, but had subsequently been diagnosed with kidney failure and was unconscious after suffering an earlier cardiac arrest.

Reynolds first hooked up with future Black Oak Arkansas singer Jim Dandy when the pair met in junior high school.

"I was born in Arkansas, but my dad was a carpenter,” Reynolds told Classic Rock in 2008. “So we had to go where the work was, and I grew up in California. I had long hair out there and when I came back to Arkansas in the 10th grade, my hair was three times longer than anybody else’s, except for Jim.”

The pair formed a psychedelic rock band called the Knowbody Else, who released a self-tiled debut album in 1969 on the Stax record label. It tanked, but the band signed a new deal with Atco Records the following year and changed their name to Black Oak Arkansas.

“There was no other group doing that kind of music then," said Reynolds. "We were the first ones to have the three guitars, the first to mix up rock, country, and rhythm and blues.

"We got a major agent in New York who was gonna book us, and Iron Butterfly were doing a farewell tour at the time, they were going to break up. So they did a national tour and we got on a bus and opened up for them, and when we came back, it was time for Grand Funk Railroad to break up, so we got their break-up tour, too."

The band were an enormous live draw and achieved some chart success, with albums Black Oak Arkansas, Raunch 'N' Roll Live and High On The Hog being certified gold, but they failed to achieve the secure the same level of financial reward as former support acts Lynyrd Skynyrd, Bob Seger or Bruce Springsteen.

“On paper it looked good,” said Reynolds. “We had a full road crew, we had a business manager back home who was hiring all these people. We donated three-quarters of a million dollars in charities to the state of Arkansas. We replaced the last one-room schoolhouse in Arkansas, we helped build a radiology wing in a hospital, we gave money to the YMCA, we got a letter from Betty Ford for our contributions to the American Cancer Society, battered wives…

"We donated a lot of money back then. So as much money as we made, we gave a lot of it away. We had our bills paid, but we never saw a great fortune."

Reynolds left the band in 1976 but returned in in 1984, and in later years the band found a new audience as old favourites like Hot Rod and Hot And Nasty found new favour amongst America's biker community.

"We found ourselves doing a dozen biker gigs a year," Reynolds said. "The two biggest biker bands are us and Steppenwolf. They’ve got Born To Be Wild and stuff like that that relates to bikers. I’ve never been able to put my finger on why they like us so much, but we love it."