May 31, 1977. On the St Louis waterfront thousands of kids are attempting to clamber aboard the SS Admiral, a 1930s Art Deco steel-hulled cruiser which looks like an alien spaceship landed on the Mississippi.

Riot cops charge the crowd off the levee. Back they surge. There’s a deafening noise coming from the Admiral. It’s being made by the band Pavlov’s Dog, local Missouri heroes who are bigger than the Rolling Stones or Led Zeppelin in these parts.

In the Admiral’s ballroom and cocktail lounge the chosen ones are lapping up favourites from the Dog’s first two albums: Pampered Menial and At The Sound Of The Bell – symphonic rock/metal mind-fuck records produced to distraction by Sandy Pearlman and Murray Krugman of Blue Oyster Cult fame.

Songs like Julia, She Came Shining and Did You See Him Cry echo around the docks, instantly recognisable from frontman David Surkamp’s extraordinary vocals.

Tall, thin and with a permanent air of distraction, Surkamp’s image matches his voice, which has been compared to Geddy Lee and Robert Plant – but he’s way wilder. He polarises opinion and challenges normal rock rules. As the mayhem increases, the Dog kick in with songs from their recently recorded but as-yet-unreleased third album.

Just two weeks after this show, however, the band will break up in disarray and disillusion. “I walked away and didn’t say anything,” says Surkamp today. “There were drug issues. Guys were on downers and speed. I took the tapes to New York City and hooked up with two former Steely Dan guitarists, Elliot Randall and Jeff ‘Skunk’ Baxter.”

Columbia Records hated the record so much that Pavlov’s Dog’s contract was taken to the top floor and ripped in half. The band were dumped, relegated to a footnote in the history of rock.

But this Dog refused to die. Thirty years after it was recorded, that ill-fated third album finally got an official release, with the title Has Anyone Here Seen Sigfried?, while today David Surkamp leads a revived version of the band. This shaggy dog story isn’t quite done yet.

Let’s rattle their chain back. The band formed in 1970 as Pavlov’s Dog And The Condition Reflex Soul Rescue And Concert Choir, under the guidance of drummer Mike Safron and bassist Doug Rayburn, who’d backed up Chuck Berry, Albert King and Bo Diddley when they were in town.

Safron wanted an orchestral rock sound “with strings instead of horns”. He brought in the flamboyant, pipe-smoking Richard Nadler, who took the stage name Siegfried Carver, brought a Wagnerian violin along and shortened the name.

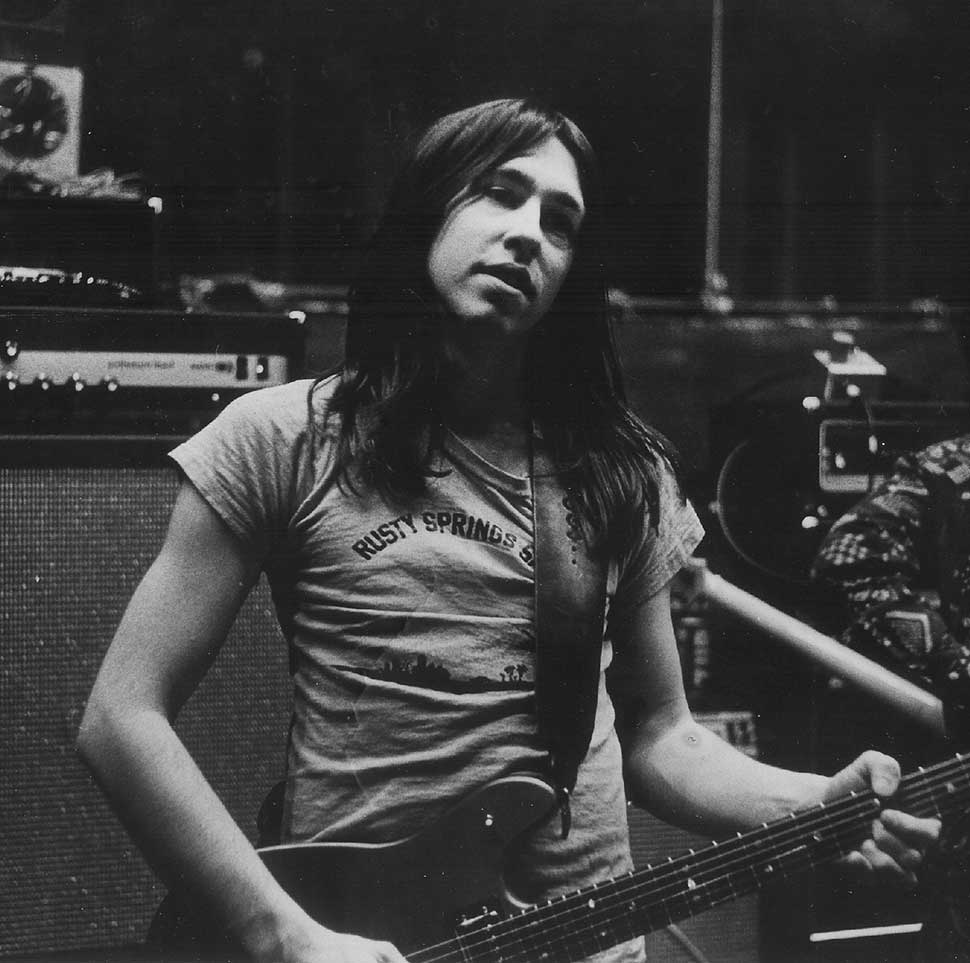

Surkamp auditioned as a Stratocaster guitarist with a Champ amp. He wouldn’t have been accepted until he sang The Wizard by T. Rex. Not everyone got his peculiar falsetto register, but this skinny kid with the waist-length hair impressed Safron.

The line-up was completed by keyboard player Richard Hamilton, a technically gifted pianist who later made a fortune writing music for TV and film, bassist Rick Stockton (Rayburn switched to Mellotron), and lead guitarist Steve Scorfina, who’d been a member of REO Speedwagon.

St Louis promoter Ron Powell managed the Dog, and soon had a number of interested labels sniffing around. Playing the long game, he signed the band to ABC for $650,000 – a then-record amount for a new band – but opted for Columbia producers Pearlman and Krugman to make debut Pampered Menial.

Just as the album was ready to go, ABC head Jay Lasker quit the label. His replacement took one look at the Dog’s sign-on fee and went nuts. ABC then swapped them to Columbia for Poco. Another fortune came Powell’s way, but the debut disc appeared in the racks under two different labels with two different covers. It bombed.

The band took to the road and toured the US constantly, playing with BOC, Aerosmith, ELO, Slade, Rush and Jefferson Starship, puzzling some audiences, delighting others and splitting opinion wherever they went. There was nothing else like them in America, and audiences could be conservative and violent.

“We built a reputation, but it could be dismal,” recalls Surkamp. Some of the venues were awful and the billings were peculiar. “We also played with Kraftwerk and Nektar. Oddly, the best gig we did was in Austin, Texas at the Armadillo World Headquarters. I thought the rednecks would hate us – a heavy symphonic rock group in a country stronghold. But it was a hip place and they went crazy for us.”

Surkamp became the focal point when they recorded At The Sound Of The Bell in New York. He was more ambitious than the others and insisted they hire top session men like Randall, former Yes drummer Bill Bruford, and Roxy Music’s sax player Andy Mackay. Bruford’s presence bemused Safron.

“He thought the whole thing was a joke. I even let him use my drums and I drove him around like I was a chauffeur. Carver and Hamilton had already left the group, and I thought the spirit had gone. When Bruford came the producers told me it was good for publicity, so I just stood back in the general interest. I was told I would be credited as a fulltime member. But when the album came out I got no credit, so I quit. They gave me $4,000 and I agreed to tour for the next few months.”

For his part, Bruford thought the band’s set-up lacked focus. “Murray Krugman asks me to do something, and I say: ‘Real bands use paper. What’s going on here? But, okay, it doesn’t bother me.’”

If the band imagined that Bruford was going to stick around, they were mistaken. After completing his task he returned home and joined Genesis as their tour drummer. Sandy Pearlman took the tapes to London for mixing at The Who’s Ramport Studios, and added the High Wycombe Boys Choir for Valkerie – to Surkamps’s delight and everyone else’s annoyance.

At The Sound Of The Bell sold better than the debut, but hit singles were still nowhere to be seen. Pearlman, who had been a vociferous supporter of the band, started having doubts. “They sounded great, but apart from Surkamp they lacked stage presence. They seemed to have a lot of keyboards players. People were pulling in different directions. In any case, by that time I was working with The Dictators and I couldn’t give Pavlov’s Dog enough attention.”

Scorfina was glad to see the back of the producers. “They swamped our records in reverb, they wouldn’t let Mike play drums, they ignored our suggestions about mixing.”

For Surkamp the problem lay within the group. “Sandy was great. He didn’t seem to interfere, he was enthusiastic and he had ideas I could understand. Murray? I didn’t know what he was talking about. He couldn’t communicate. He couldn’t count time properly. He’d say do this, do that, and I didn’t have the slightest idea what he meant.

"I wanted to try something wonderful, which is why I insisted on the session men, but I also had a clear idea of what I wanted, and the others didn’t. My instrument was my voice, and my songwriting, which is romantic, nostalgic and about love. I’m not a hit machine. I’m not the Brill Building. There was a lot of pressure. I may be an acquired taste, but no one will ever accuse me of shoplifting any tunes. I’ve always staked out my own territory."

The third album would be make or break. Pavlov’s Dog camped out on the floor at one of their strongholds, the ornate Ambassador Theatre. And since Powell had tied up the advance for the purposes of cocaine dealing, they were forced to use a local jingle studio, Technosonic, and new producers John Jansen and Mark Spector, who had worked with Jimi Hendrix and Tom Rush respectively, but couldn’t fathom Pavlov’s Dog.

“It was a mess,” says Surkamp. “I liked Mark. We spent a lot of time wrestling in the studio and playing with my Boston terrier Charlie, who used to sleep in the bass drum even while we were playing.”

Columbia heard the tapes and rejected them, so Surkamp and Doug Rayburn colluded with Powell, stole the masters and flew to New York’s Record Plant where they enlisted ‘ringers’ Randall and Baxter and hot young drummer Jimmy Maelen (who later played on Roxy Music’s Avalon and a string of NYC disco hits).

“I rewrote the album in two weeks,” says the singer. “Elliott and Jeff played great guitar and helped produce the new mixes. They were expensive, but cheaper than wasting time in the studio in St Louis. Everybody else in the band suddenly thought they were songwriters, even though only Scorfina and me had written before. Randall and Baxter didn’t care about that. Elliott liked the songs and Jeff liked playing, and since they are fantastic guitarists we arrived at a more satisfactory conclusion.

"Baxter was funny. He smoked a lot of pot, and when he wasn’t playing he seemed to spend his time having huge arguments on the phone with the Doobie Brothers screaming about his royalties.”

Even so, Columbia stopped returning their calls. “They went cold. They didn’t like it at all. And since I’d quit the group after the riverboat show the band didn’t have a lead singer. You couldn’t blame them. Bizarrely, the group tried to carry on without me, using a guitar technician as singer. They ended up sounding like a southern rock group. That didn’t really fly.”

Ironically, Pavlov’s Dog’s third album suddenly became a matter of importance. It was a mystery. It even had a title: Has Anyone Here Seen Sigfried?, which related to Carver’s departure, and was a belated attempt to woo him back. Sigfried actually made a surprise appearance on the Admiral, puffing his pipe in Spinal Tap fashion, and the audience erupted. But he detested record company politics, and left to form a right-wing taxpayers alliance group with strong opinions on immigration (Carver/ Nadler died in 2009).

Surkamp believes the band should have moved to Europe. “We got no support at all from the American media, but plenty from the press over there. Rolling Stone ignored us altogether, and I remember that Creem magazine reviewed Pampered Menial with Flo and Eddie from The Turtles, who just made fun of us.”

This shaggy Dog story has no punchline. Renowned in St Louis as the city’s hippest kid – the teenager who’d walked around town with sacred knowledge of the new British sounds – Surkamp packed his bags and headed for Seattle with a few dollars, a Fender 12-string and a Mellotron.

“I had no regrets and fewer possessions. Eventually I hooked up with Ian Matthews. “I was definitely an Anglophile. I saw the Ziggy Stardust show at the Kiel Opera House. I saw King Crimson. I saw Genesis with Peter Gabriel. None of them sold out more than the first few rows; we packed those joints. Bands like Fairport Convention and Pentangle made total sense to me. The first time I heard Tubular Bells I said: ‘Yeah, that’s good.’

"My vision was that we were an orchestrated electric folk group. I know we were hard to label. Later on, people said we were prog, maybe because we had too many keyboard players and a violinist.”

Typically, the legend of Pavlov’s Dog grew in their absence. Some said that Surkamp had committed suicide, imbibing a lethal dose of helium.

“That’s the most ridiculous part of the legend,” he laughs. “Mental health issues run through my family. I’m an eccentric. I was always sick as a kid. I can’t deny that. My mother made dolls. Real beautiful dolls. I like Segovia. But I’ve just turned 60 and I’m still Pavlov’s Dog. I always will be."

This feature was originally published in Classic Rock 173, in July 2012. The band's most recent album Prodigal Dreamer was released in 2018. Pampered Menial, At The Sound Of The Bell and Has Anyone Here Seen Sigfried? are all available from Rockville Music.