It’s 2002 and the sun is shining on a rehearsal space in London's Turnham Green. The 21st Century Schizoid Band, in its original incarnation with Michael and Peter Giles, Mel Collins, and Jakko Jakszyk, are blasting their way through an incendiary version of 21st Century Schizoid Man. Ian McDonald, with the look of a slightly preoccupied professor, puts his alto sax to his lips and fires off a volley of careering notes that spatter and shape-shift around the backing in the track’s twisting instrumental section. It seems so incongruous that such a furious salvo of notes could issue from someone who offstage was quiet, reserved, and more often than not, self-effacing.

In 2003 after the band had been on tour playing King Crimson-related material and one or two songs from his own solo catalogue, Ian said, “One of the most enjoyable aspects of doing these shows is meeting audience members after the gig, to sign autographs, and shake hands, etc. It’s really good to hear their comments and stories. It’s very gratifying to hear such things as: ‘I’ve been waiting 30 years to hear these songs!’ In some cases, so have I.”

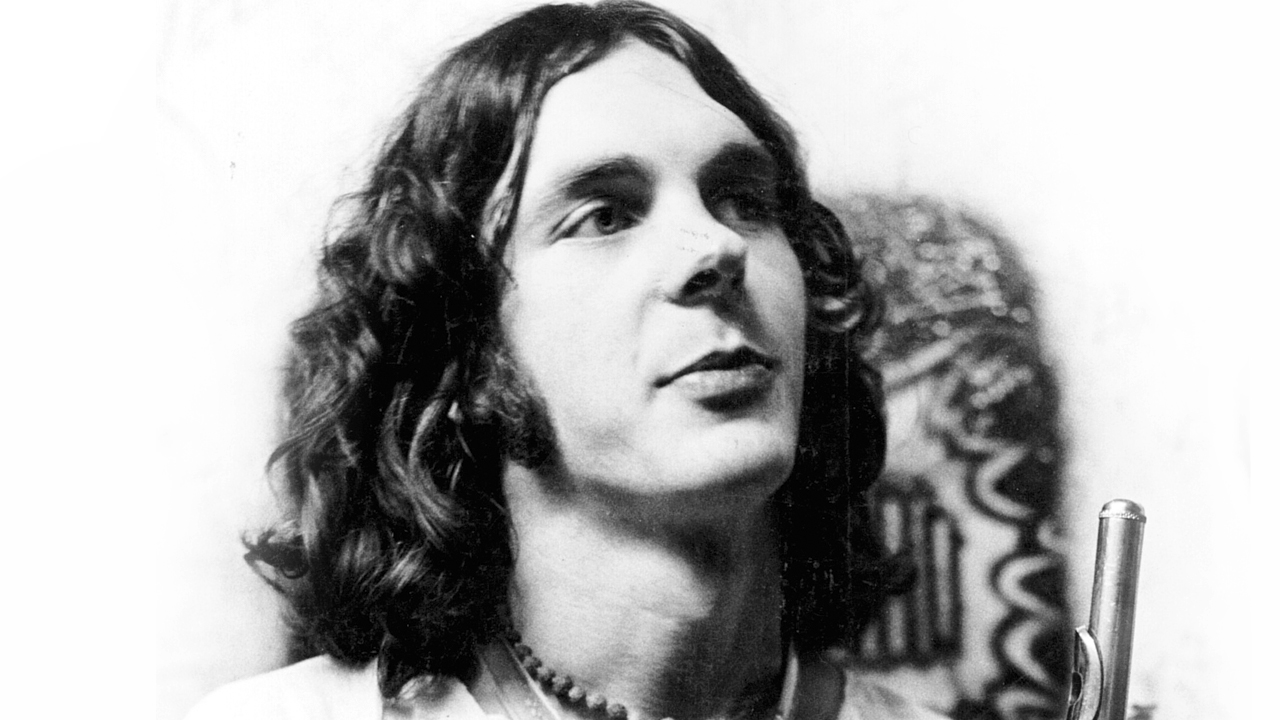

The death of Ian McDonald from cancer in his beloved New York is the closing chapter on a remarkable career. Having been a crucial factor in the formation and subsequent success of King Crimson in 1969, and thereby close to the epicentre of the progressive rock movement, in 1976 he reinvented himself upon emigrating to the USA to co-found AOR rockers, Foreigner. For some, the juxtaposition of those two polar opposite bands seemed wildly incompatible. As far as McDonald was concerned, uninterested in any tribal or generic considerations, it was simply all about music.

In assessing the qualities of the founding members of King Crimson, Robert Fripp once observed that what Ian brought to the table was “musicality, an exceptional sense of the short and telling melodic line, and the ability to express that on a variety of instruments."

King Crimson’s debut album is filled with McDonald’s multi-instrumental presence on flute, saxes, woodwind, vibraphone, various keyboards, and of course, arguably the album’s signature sound, the Mellotron. Alongside all of that technical virtuosity, built and honed during his stint as an army bandsman in the mid-1960s, Ian was blessed with an ability to write and compose, something he often did on guitar.

Following his discharge from the forces, he fell in with Peter Sinfield and later, Judy Dyble. Upon hearing what Sinfield described as his Donovan-like ‘country and western’ ditty, McDonald politely but firmly discarded Sinfield’s original tune and provided his own. The result was The Court Of The Crimson King, and the creation of an anthemic tune whose impact upon the emergent progressive music scene in the 1970s and beyond would be deep and lasting.

1969 was a year of emotional turmoil, including the highs of playing in front of 650,000 people supporting the Rolling Stones in Hyde Park, and the depths of lovesick despair while touring America. Unable to cope, he and drummer Michael Giles abruptly quit. It was a decision he regretted for a very long time but in more recent years had finally come to terms with.

For someone so closely associated with the sound of the Mellotron, it was an instrument McDonald disliked having had to wrangle with its volatile nature on stage one time too many. Thus he opted to use a string orchestra on McDonald & Giles which the pair released in 1970 and which was, at that point, the most expensive album Island Records had recorded, thanks in part to McDonald’s insistence on using orchestral players. The resulting album is criminally underrated and unfairly overlooked. For years it was a source of great personal pain to McDonald that he was rushed into finishing the album. In 2002, when the album was properly remastered for CD, he flew to London in order to make some small adjustments and edits. “After 32 years, I can finally relax now,” he later told me.

Following McDonald And Giles the pair went their separate ways. 1971 saw him appear on records as diverse as T.Rex’s Electric Warrior, including the hit single Get It On, for which he borrowed Mel Collins’ baritone sax, and, at the other end of the commercial spectrum, the free-jazz and rock ensemble opus, Septober Energy by Keith Tippett’s Centipede, underlining his view that all music had a value regardless of stylistic considerations. Production work beckoned including Canis Lupus by Darryl Way’s Wolf in 1973, and after his guest spot on King Crimson’s Red in 1974, he went on to produce Fruup’s Modern Masquerades in 1975 and American proggers’ Fireballet’s debut Night On Bald Mountain the same year.

McDonald always understood the importance and impact that the music he was involved in had upon listeners. It was a bond he felt deeply. Meeting fans was something he enjoyed and during stints with Steve Hackett in the 90s and later, the Schizoid Band, he was often profoundly moved by the reaction to the music he had a hand in creating.

Attending shows by the current King Crimson he was pleased with what he saw and heard. “They played music drawn from later albums but they did do Epitaph, Moonchild, Court, and Schizoid Man, and it sounded great, especially Epitaph, which they performed beautifully. That was really nice and in a sense an interesting experience for me being in the audience and being detached from the performance and these tunes that I had co-written. It was a pleasant experience to hear the early tunes played so well. I had heard from other people that when they played songs from In The Court Of The Crimson King there was a kind of gasp in the audience and not just here in New York,” he told me in one of the many phone calls we exchanged over the years.

A gentle, sensitive man and never one to brag or boast about his considerable instrumental abilities or musical achievements he was nevertheless rightly proud of his contributions. I recently asked him about the making of that totemic Crimson debut. “One of the things I’ve always done when I’m recording a song is I ask myself, ‘Could I listen to this 500 times?’ So you have to be honest with yourself when you are making a record. All the while in the studio when we were recording the album I was thinking, ‘Will I still want to listen to this in 50 years' time.’ So part of me was thinking 50 years ahead if you like.”

The thought that people will still be listening to his music for another 50 years and beyond, is something that would have pleased Ian enormously.

Buy the latest issue of Prog Magazine.