There’s a palpable sense of relaxation if not outright serenity emanating from Nad Sylvan. The Danes and Norwegians call it ‘hygge’ – a mood of domestic coziness and contentment – whereas over in Sweden, which is where we find Sylvan, the locals refer to this concept as ‘mysig’. But whichever of these Scandinavian notions of creature comforts you plump for, Nad Sylvan is radiating it.

“I’m about 30 miles south of Stockholm city out in the wilderness,” he explains from his home. “I’m out in the country and live in this 26-year-old log house that was imported from Finland by a Finnish couple who used to live here. They got divorced, the house came on the market and I fell in love with it. So I bought it.”

Sylvan is something of a country boy at heart: “My first 47 years I lived in the city.

I lived in Malmö and Stockholm. We had a summer residence in Gothenburg and we also had a cottage in West Cork in Ireland and so I always loved the rural life. I was always drawn to that. After so many years in the city – I was approaching 50 – I thought this must be the time in my life where I settle down, so I bought this house. I’m happier than I’ve [ever] been.”

Prog suspects that a large part of Sylvan’s happiness is down to the upswing of his solo singing career. It’s been a long road. While he’s arguably better known as the vocalist in Steve Hackett’s Genesis Revisited project, Sylvan has been chipping away at music’s coalface since the halcyon days of prog in the 70s. His dedication to the cause saw him become a key figure in prog’s Swedish revival in the opening overs of the 21st century where, following two solo albums, The Life Of A Housewife (1997) and 2003’s Sylvanite, he collaborated with compatriot and multi-instrumentalist Bonamici (that’s Christian Thordin to his mum) in the shape of Unifaun, who released their eponymous and only album in 2008. This was swiftly followed by the co-founding of Agents Of Mercy with The Flower Kings’ linchpin Roine Stolt, who released three studio albums – The Fading Ghosts Of Twilight, Dramarama and The Black Forest – in a particularly fecund burst between 2009 and 2011.

And then, of course, there are Nad Sylvan’s further solo releases.

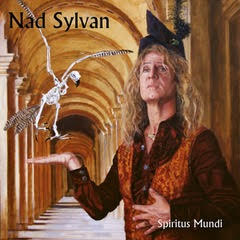

“I’d done a trilogy of albums and of course you wonder, ‘Where do I go now?’” says Sylvan as he ponders the origin of Spiritus Mundi, his latest and sixth solo album.

And who can blame him? After spending three albums – Courting The Widow (2015), The Bride Said No (2017) and The Regal Bastard (2019) – in the company of his Vampirate character (a fusion of vampire and pirate), it was clear to Sylvan that a change was needed as much as it was wanted.

His new direction is fully in evidence with Spiritus Mundi. Working with Canadian multi-instrumentalist and songwriter Andrew Laitres, Sylvan’s latest work sees the pair bring music to the poems of WB Yeats. As Sylvan explains, the project took began to take root as he was bringing The Regal Bastard to a close.

“Andrew asked if I would be interested in tracking my voice for a song of his for his solo record [recorded as The Winter Tree],” he recalls. “I listened to it and I thought, ‘Nice melody! I wonder who wrote the lyrics?’”

Unbeknown to Sylvan, these weren’t lyrics but the poem The Lake Isle Of Innisfree. Concerned with the longing for the tranquillity of the countryside in the face of being overwhelmed by city life, it’s not difficult to see how the poem’s central theme would have appealed to Sylvan. So much so, in fact, that it also appeared as a bonus track on the final instalment of his Vampirate trilogy. The seeds had been sown and were soon taking root.

William Butler Yeats is one of the most intriguing figures of 20th century literature. In addition to his poetry, he was also a celebrated dramatist and prose writer who did much to revive the Irish literary and storytelling tradition. An occultist and spiritualist, he joined the secret society The Hermetic Order Of The Golden Dawn, whose members included the writers Bram Stoker and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle as well The Great Beast himself, Aleister Crowley, with whom he developed a feud over questionable lifestyle choices. An ardent Irish nationalist, he was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood before serving two terms as a Senator of the Irish Free State.

With such a huge body of work that leads from an early romantic idealism through to a more pragmatic realism, the appeal of WB Yeats as source material for a musical project is entirely understandable. Indeed, Yeats has been reinterpreted by a variety of musicians including Christy Moore (The Song Of Wandering Aengus), The Chieftains (Never Give All The Heart) and The Waterboys on their own full-length project dedicated to the poet, An Appointment With Mr Yeats.

“I knew that The Waterboys had done something similar but this a completely different take,” says Sylvan.

He’s not wrong. Although fundamentally acoustic in its approach, Spiritus Mundi eschews the folk default setting of previous interpretations into something more pastoral, considered and direct. Indeed, compared to Sylvan’s previous releases, this is an album that’s characterised by a simplicity of arrangements and a feeling of space that gives room to Sylvan’s voice as much as it does the instrumentation surrounding it.

“I wanted to go very organic and I think it worked really well,” states Sylvan. “Here, you have the poetry holding it together and Andrew’s acoustic guitar holding it all together. This is a much more coherent album than I’ve ever done before.”

Sylvan admits he wasn’t altogether familiar with the work of Yeats prior to the project. Yet for all that, the poems possess a resonance and meaning that are every bit as relevant now as they were when they were written. The album’s opening numbers – The Second Coming and Sailing To Byzantium – are easily songs for the here and now. The parallels with the former, written in the aftermath of the First World War and against the backdrop of the 1918-19 Flu Pandemic, are easy to see. Drawing on Biblical symbolism, here the death of the old world is replaced by the rebirth of a new one, an apt metaphor as our world begins to look ahead. Similarly, it’s not difficult to see some of Sylvan in Sailing To Byzantium, a paean to the spirit and wisdom that nestles down with the oncoming autumn of life as well as the endless battle between spirituality and the physical form.

But if there’s friction at the heart of those words, then how much of challenge was it for Nad Sylvan and Andrew Laitres to turn the source material into songs?

“It was very different from my usual routine of writing because the lyrics come last because I always focus on the melody,” admits Sylvan “This time around, Andrew had already come up with some of the song structure and melodies. I pretty much sang what he came up with, only I would paraphrase and maybe try something different.”

Despite the circumstances of its creation that found musical files being sent back and forth across the internet, Spiritus Mundi is an album that boasts an impressive cast of supporting characters including bassist Tony Levin and The Flower Kings’ rhythm section of Jonas Reingold and Mirkko DeMaio. Oh, and a certain Genesis guitarist who plays on bonus track To A Child Dancing In The Wind.

“You can clearly hear that’s Steve Hackett; it’s his way of playing and it sounds like something from one of his records,” says Sylvan. “I thought it was a nice way to end the album and it gives you a lot of after-thought.”

Since delving into the works of Yeats, Sylvan has come to see some of himself in the poet. But which aspect is it? Is it Yeats the occultist? Yeats the politician, perhaps? Or could it be Yeats the reviver of the Irish literary tradition?

“He’s just like me – he was absolutely obsessed by the occult and sex!” jokes Sylvan.

Composing himself, Sylvan ventures: “On the more serious side, he was misunderstood by his contemporaries. Not always, but there was a phase in his life, especially when he wrote the poem The Fisherman: ‘The living men that I hate/The dead man that I loved…’ his contemporaries didn’t understand what he wanted. He has more reverence and respect for the past times. This is of course his ageing and, in a way, I feel the same. I don’t really feel I belong in this world, to be honest. Throughout 40 years I was trying to get somewhere with my music; I was always rejected and always overlooked.”

Sylvan continues: “But endurance is the key, I guess, but he was more successful in his day than I was. I feel in a way that he’s a kindred spirit and I can connect with the lyrics very much and I think they’re so strong. Complexity also within a person, I guess that has to deal with very broad references to life and being able to solve a lot of things rather than just going through life. You take it all in and it becomes a melting pot in your mind. That’s very much Yeats and it’s very much me.”

And from a purely Yeatsean perspective, Nad Sylvan sees himself as idealist rather than a realist.

“One hundred per cent idealist,” he asserts. “Realism, I try to avoid it because it’s too depressing. I like to create my own little space in my own world. That’s why I bought this house out here so I don’t have to have any stomping neighbours on the floor and people banging on the radiator like they did when I lived in my apartment. I’m an idealist and I sort of believe in hanging on to my own values and not being put off by negativity from outside my bubble.”

Sylvan allows himself a smile: “I was always driven by my music. And whether I liked it or not, it was never a question of quitting. I did not have any success for about 40 years but that didn’t seem to matter. It was all about expressing myself through music. And I’m not a trained musician; I’m completely self-taught. I don’t read music but I have a very good ear.”

And judging by his use of WB Yeats’ poems, he’s got very good eyes, too.

This article originally appeared in issue 120 of Prog Magazine.