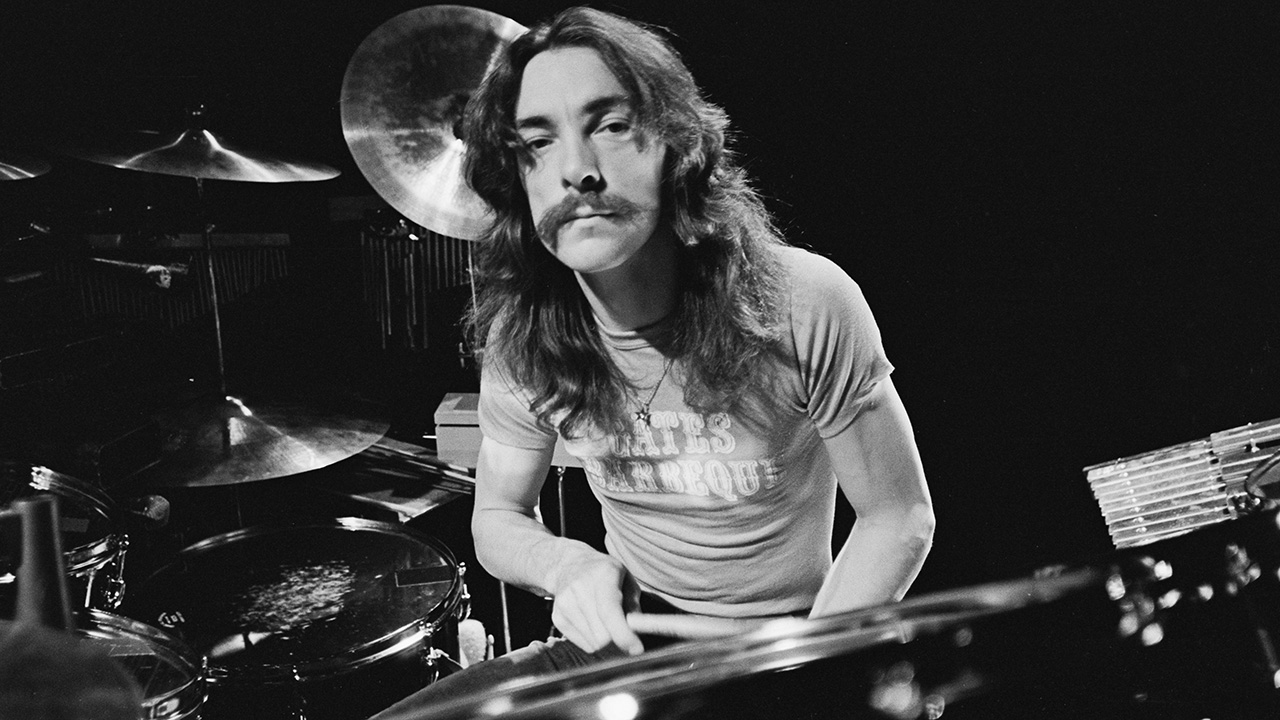

He would have hated this, of course. Accolades and adulation hung on Neil Peart like a bad suit. One only has to listen to Limelight to understand the consternation being the focus of attention brought him. He’d have run an eye along this list, brow furrowing incrementally as he looked down at the great and the good of prog and realised that he was standing on the shoulders of giants. A small smile, though, at numbers four and nine; wait until the guys hear about this.

It’s been less than a year since we lost Neil Peart. Some days it feels like he’s been gone forever and others, when, out of context, you hear a familiar fill from Xanadu or a line from Losing It, you can forget he’s gone at all. And then in that brief flicker of memory and heartbreak you remember, and the clouds roll in again. He’d have just turned 68 and would probably have been tooling around in his man cave: a generous garage attached to his Californian home that was filled with his collection of Aston Martins, gleaming a burnished silver in the overhead lights.

He once gave me a ride in one of those cars, a series of tight Californian hill-turns screaming down towards the Pacific; he drove like he played drums, with real intent. We were as close to the road as I’ve ever been in a car – it felt like we were sitting on the floor, the endless Californian sky a blur of intermittent blue above. He was about to turn 60 and life was coming at him fast, but he was wide open to it, tuned into the universe. Clockwork Angels was at the mixing stage and sounded so fresh and full of promise. He was already in training to go out on tour. He was brimming with happiness, ready for the next thing.

“How do I feel about turning 60? I feel proud as hell,” he said as we passed another car that may as well have been parked given how effortlessly he went by it. “I’m at the height of my powers in one sense, but also I can’t help feeling the empathy for someone like Keith Moon: he never got to be 59. Dennis Wilson, neither. John Bonham… These are cautionary tales in a sense, but they break my heart: they had children, they had loved ones, they never got there, they never got this. This kind of career.”

No one knew that Clockwork Angels was to be Rush’s last album, that, much like his characters in Losing It, Neil would feel a disconnect between himself and his playing, that he felt he wasn’t at his physical apex anymore. That was all to come, but on that balmy Hollywood afternoon, Neil Peart was still growing into himself. He’d relearnt how he approached playing his drums: think about that for a moment. Imagine playing at that extraordinary level all your life and then thinking there were still things you could do better, that you could improve on, so you go back to the drawing board. It’s like Monet stepping back from his easel one day and saying, “Bloody waterlilies! What was I thinking?”

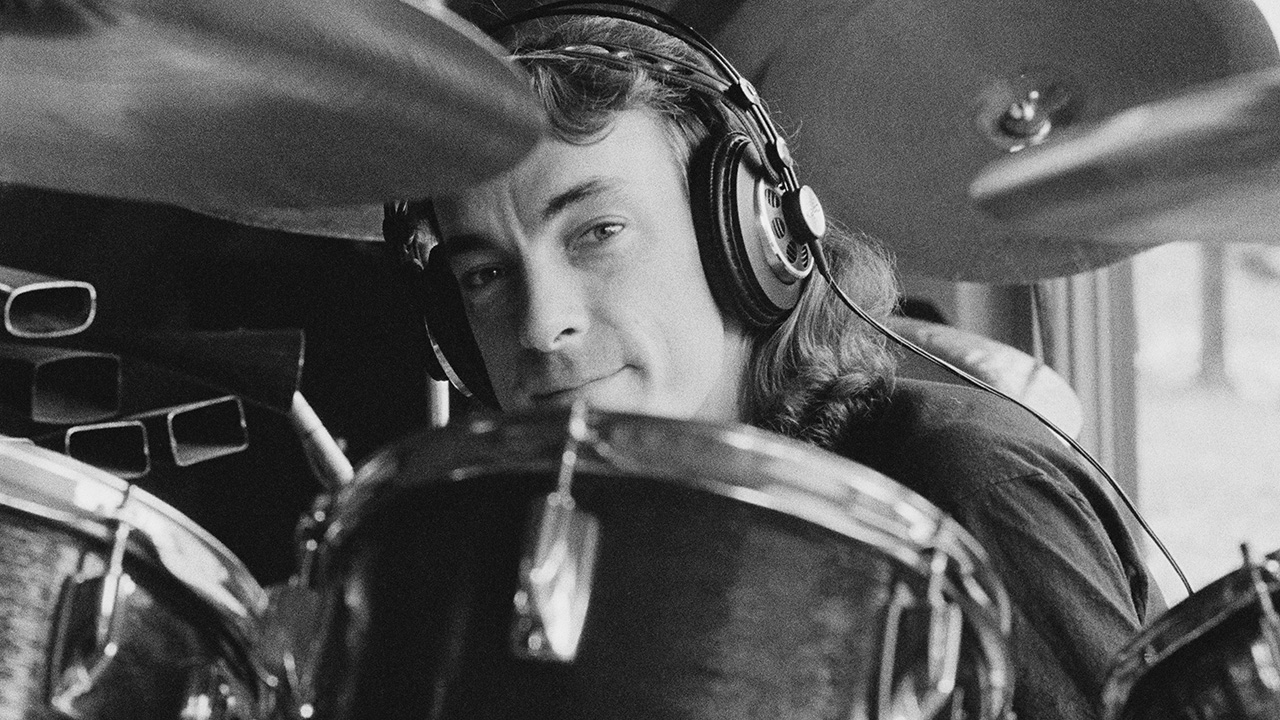

His approach in the studio had gone happily out of the window, too. Not least in part to producer Nick Raskulinecz. Neil had gone from preparing his parts, writing his fills, charting all those bells and whistles, to simply going with the song. His inherent metronomic rattle was still intact, but now he was flying off at tangents in songs like the appropriately titled Headlong Flight, Nick standing before him, a drumstick in hand, conducting Neil as the sound booth filled with the rattle and hum of his drumming. I once sat looking through the glass with Geddy in the production studio, talking, as I remember it, in hushed tones, as if Neil might hear us. “Look,” said Ged, as Neil hit his snare with the intensity of a 20-year-old. “Look at him.”

Later, sitting out in the LA sunshine in the shadow of the Henson Studios, Neil was thrilled. “Nick goofs around, but the enthusiasm and the energy is fantastic.” He recalled: “The first time we worked together he asked me to play something, and would mimic it and sing the parts, and it would be so over the top, just extraordinary, I’d be ashamed to throw a fill like that in myself. But I’d be like, okay and then I’d pull it off and he’d be, ‘That’s great!’ It’s like the Caravan drum fill that I laid out, we went back into the booth to listen and Ged looked over his glasses at me and said, ‘Oh, he wants to make you famous.’

“This time, it was more immediate. He was in the room with me, not listening to playbacks – he was right there, so that every time we stopped, we’d be conversing over the parts. He was playing along with me; I didn’t have to learn the arrangements.”

Neil was always evolving, always in that headlong flight, which is what, I imagine, some of you who voted for him saw. That he was a musician in the most progressive way; he had itchy feet, whether it was travelling independently from his band when they toured, making the transition from bicycle to motorbike (even though motorbikes scared him at first) for those long journeys or finessing his playing or pushing at his limits. Hiking, cross-country skiing, his role as a writer – musical as well as non-fiction; his tales of travel; always there in pursuit of excellence or the higher ground at least. Finding new ways of doing things or simply doing them better. Some of us pretend we’re on life’s highway, chasing after the next thing – but Neil was, almost daily.

The sun was shining over Topanga Canyon, lunch was long over, but neither of us were moving. Neil, the impish Neil that people missed when they assumed that the stone-faced drummer on stage was all there was, looked conspiratorially around and ordered more drinks. We were talking about that new-found freedom in his playing on the band’s last Time Machine tour, which had found its way in to the Clockwork Angels sessions.

“There was no plan, that was all unknowing,” he said. “I started that a few years ago when I studied with Peter Erskine [Weather Report, Kate Bush]; part of what he taught me was with the metronome and hi-hat only, and I came out of that with a sense of time. I can listen to two things now and go somewhere really far outside and still draw back and drop in, so there’s so much more stuff that I can get away with.”

Two things still strike me about that: in some way Neil Peart must have somehow felt that he lacked a sense of time (this from the man whose drum solos were so entrancing that even Ged and Alex would sometimes stop to watch them from stage side), and how excited he was by the idea that his playing was evolving, that it still had somewhere to go.

Neil Peart played drums every day of the year apart from Christmas Day. He used to play for an hour before he went on stage. “He plays to play,” Geddy told me once with an affectionate roll of his eyes, as Neil half-destroyed his practice kit in the adjoining room. And then when he lost both his daughter and then wife in the space of less than a year, he put down his sticks and really didn’t pick them up again for two years. He lost that part of himself. The story’s well told: he got on his motorbike and disappeared into the sky, no one knew where he was or where he was going, or as Alex said some years later, “We didn’t even know if he’d come back.”

When he did, Peart started from scratch again. After the sessions for the album that would become Vapor Trails were done for the day, Geddy would head home and Alex and Neil would stay late into the night and work on Neil’s chops, so that he might become the drummer he once was, to play the way he wanted to play again. Music binding them tight. It’s strange to now think that Neil wasn’t even the drummer Rush wanted after John Rutsey left the band.

“We had this other guy who played with friends of ours, Max Webster,” said Geddy. “And we tried to poach their drummer and he said yes and then a few days later he said no. So that’s why we had the auditions and Neil was the third guy to come in. We auditioned four and I felt for the fourth guy having to follow Neil, who’d want to be that guy? I felt so bad for him because he had written charts of the first album and he was sitting there playing while reading the charts and he was very polite and we had just experienced this whirlwind that was Neil. We were just being polite, playing out the string, as they say.”

Happier days, long ago, before Rush had even begun to forge their legend. Once, it might have been Hollywood or Nashville, it could have been a damp Toronto, Alex and I talking about Wales and the recording of A Farewell To Kings at Rockfield Studios.

“For the title track, we set up on the cobblestone courtyard outside with a pair of mics and created our own stereo spread. I do recall walking back and forth, trying to concentrate on my playing while not crashing into Neil. It was quite surreal – Neil there with his full studio setup, with one eye on the sky waiting for it to rain. They’re good memories, the way the three of us made that record, the organic nature of it.”

Strange to think now that at one time all we hoped for was a Rush reunion and now all we can wish for is that Neil had stayed in any capacity at all, there in that great garage of his, a book in one hand, a good malt in the other. The music still lives, though, and no one can take that away from us, each ringing note enduring down the years, a grin sitting behind that stony face etched with concentration, a whirl of life as he rattles around his kit for one last time. The wave of the hand from the lip of the stage and then gone.

I’ll leave you with this comment from Geddy. He was at home in his library, and I still don’t know why I asked, but I did: when was he at his happiest in Rush?

“I’ve never thought like that before,” he said, “but I can tell you that ever since we came back after Neil’s terrible tragedy with his family, and having had those five years, those five dark years we were away, every tour I did with Rush I savoured. I would say that period from coming back after Neil’s tragedy to the very end were really the golden years for me. I felt like I appreciated every gig, every note that we played. The camaraderie that the three of us had, I never took if for granted, not one day. So I would say that was my happiest time in Rush.”