On 15 December, 1974, Joe Perry was tooling around with a riff at a soundcheck in Honolulu. The Aerosmith guitarist often warmed-up with some James Brown and had been listening to New Orleans funk band The Meters, a band renowned for their choppy, minimalist grooves. The band jammed around the funky riff he’d come up with and later that month tried working it up in the studio during the recording of Toys In The Attic in New York.

At a break in recording, the band went to see Mel Brooks’ movie Young Frankenstein. Tickled by the famous scene in which Marty Feldman’s Igor asks Gene Wilder to “Walk this way” and Wilder doesn’t just follow but also copies Igor’s limp, the band told Steven Tyler: “There’s your title! Get writing.”

Tyler rose to the challenge, eventually penning a lyric about teenage sexuality, from the point of view of a young man learning how to please women. “Walk this way” became a euphemism for fingering a girl’s clitoris – letting your fingers do the walking – while “talk this way” became an instruction for how to properly go “down on the muffin”. In doing so, it became one of the few male-penned rock songs about female pleasure, perhaps no surprise from a band whose Get Your Wings logo featured a winged, hairy ‘A’ with a clitoris.

Tyler had started out as a drummer and had developed a percussive singing style. The verse lyrics of Walk This Way were delivered as a series of snappy rhymes, a funky rap that made perfect sense when Run DMC later covered the song in 1986. The Run DMC/Aerosmith version became a cross-cultural hit, rescuing Aerosmith’s career, and putting rap music on MTV and into the bedrooms of white teenagers across the world. For a track inspired by the grooves and rhythms of black America, it was a sweet bit of karma.

So, Walk This Way: a sex-positive, multi-cultural force for good, with a big beat, a killer riff and a giant chorus that’s entertained two generations of rock fans. Right?

When the Classic Rock team prepared to talk about the song for our latest podcast, we realised that we had to consider some things that could change the way we – and you – think about the song.

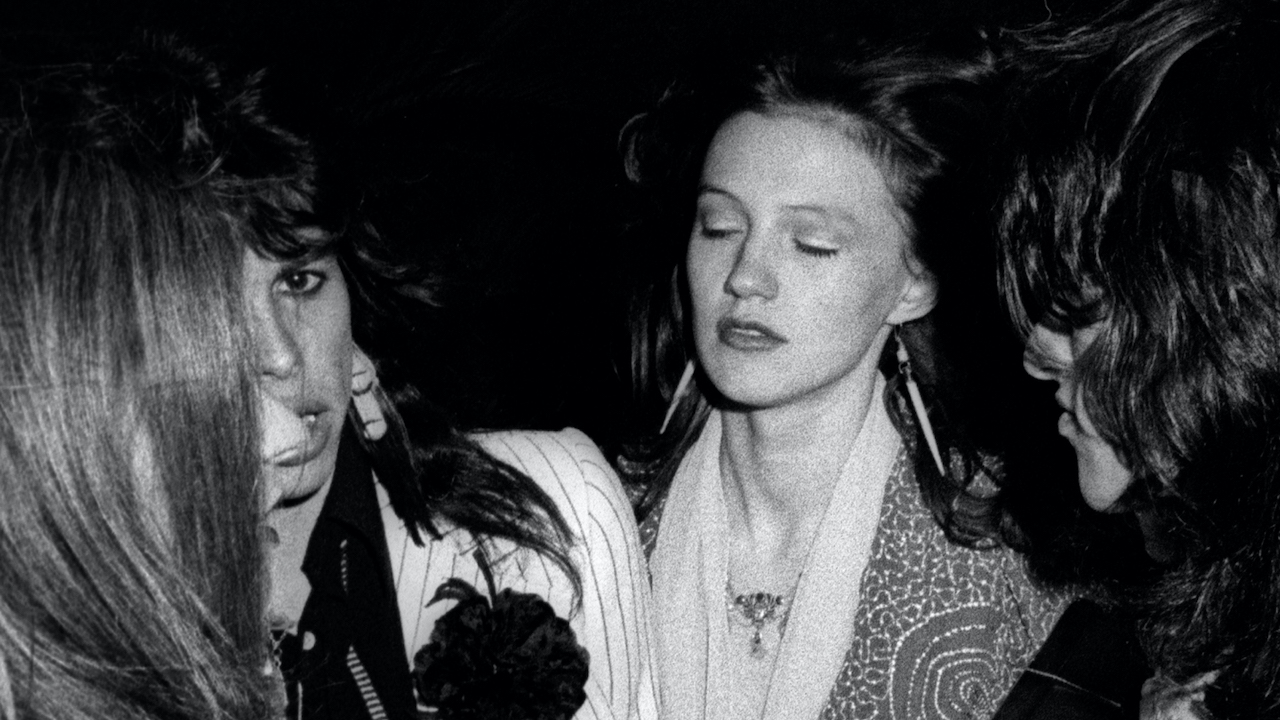

A new documentary on Sky about sexual abuse in the music industry, Look Away, focuses a large part of its running time on the story of Julia Holcomb and Steven Tyler. When Holcomb was 16, she went to an Aerosmith concert with the intention of hooking up with Tyler. She was young, from a broken home, and looking for excitement. Her older friends dressed her up sexily, and backstage she and Steven Tyler just clicked. They were exactly what each other were looking for. Tyler was 25.

They were together for three years from 1973. Age of consent laws vary from state to state in the USA, which meant that Tyler could get into real trouble with a 16 year old girlfriend. To get around it, Tyler asked Holcomb’s parents if they would sign her over to him as legal guardian. They agreed. (Holcomb has since claimed that Tyler lied to her parents, saying that he needed guardianship to enrol her in a school.)

Either way, Tyler became Holcomb’s lover, guardian, and eventually her fiancee. Holcomb says Seasons Of Wither was written for her. In it, Tyler casts himself as the devil and suggests their relationship will end badly: “Blues-hearted lady sleepy was she,” it goes. “Love for the devil brought her to me… Ooh woe is me I feel so sadly for you/In time bound to lose your mind/Live on borrowed time/Take the wind right out of your sail”.

He was on the money. The end came after a fire at their apartment. Holcomb was hospitalised for smoke-inhalation at five months pregnant and says she was coerced by Tyler into having a late-term abortion. The relationship ended soon after. Holcomb is now a mother of seven and a pro-life spokesperson.

Steven Tyler isn’t interviewed in Look Away but his side has already been well-documented. One of the most surprising things about this story is that it’s been public for years. In the band’s official biography Walk This Way, from 1997, Tyler recalls their meeting: “She was a skinny young malchick, much younger than me, like 14 when I met her in Seattle backstage after a show. She was there with a bunch of her girlfriends and they were acting bisexual to get my attention.”

(In the same book, Aerosmith publicist Laura Kaufman also claims that Holcomb was 14, and that timeline is followed throughout the book: when Julia becomes pregnant in 1976, two and bit years after their meeting, Tyler writes: “Diana [the pseudonym the book uses for Holcomb] was with me, 16 years old and pregnant”. Holcomb’s most recent accounts confirm that she was 16 when they met, so presumably it’s just a mistake. That in itself tells you how lightly this stuff was taken, even in the 90s. Can you imagine making that mistake today?)

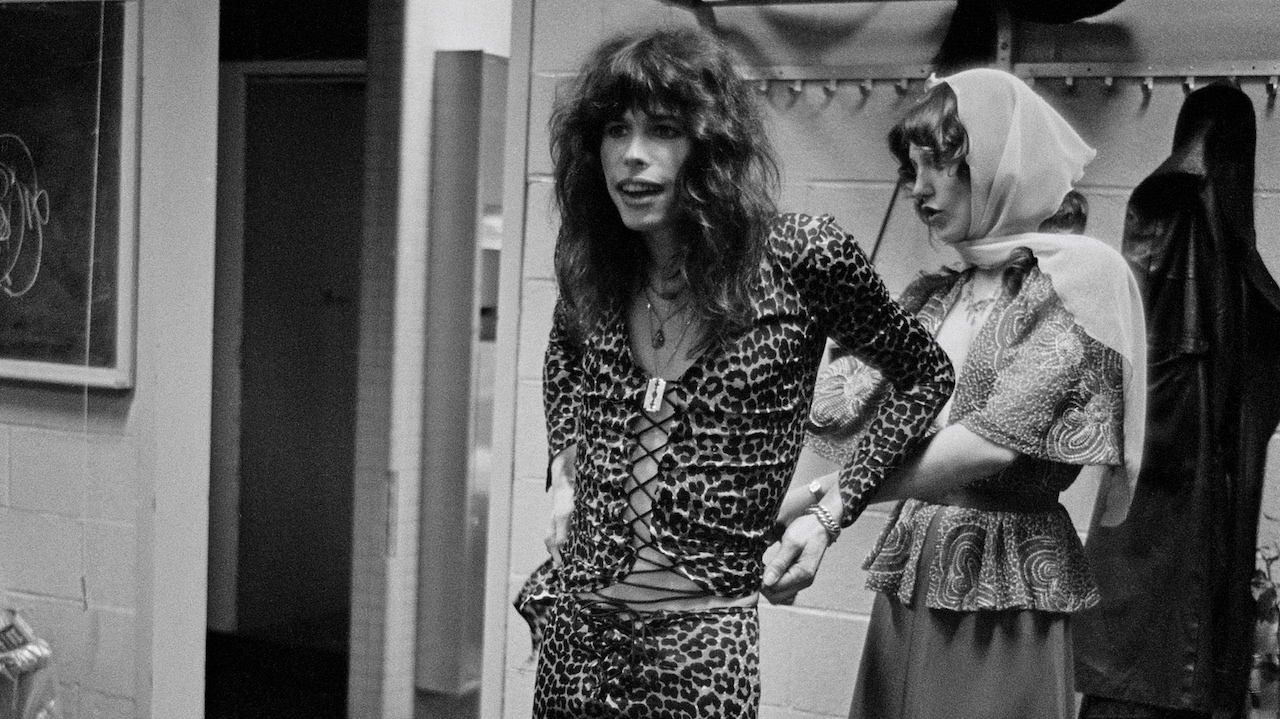

In Steven Tyler’s memoir Does The Noise In My Head Bother You? (2012) Tyler claims that when they first met Holcomb was a with a group of girls who called themselves “the Little Oral Annie Club”. Of Holcomb (who he doesn’t name) he says: “She was 16, she knew how to be nasty, and there wasn’t a hair on it. With my bad self being 26 and she barely old enough to drive and sexy as hell, I just fell madly in love with her. She was a cute skinny little tomboy dressed up as Little Bo Peep.”

PR Kaufman said that she believed that Tyler must have really loved Holcomb: to get guardianship “took lawyers and cost real money. I remember thinking he must really love her to go through with this… She was no piece of meat to him.” That said, “He dressed her up as Little Bo Peep, made her wear outfits, for God’s sake, little schoolgirl frocks. No one could believe this, it was so outrageous.”

“Schoolgirl sweetie with the classy kinda sassy/Little skirt’s climbing way up her knees.” Those lyrics are fine if you accept that they’re written from the POV of a teenage boy, and that is all you know. But when you consider that Tyler wrote those words while living with a teenager that he was dressing up as a schoolgirl?

That’s a little bit more difficult.

There is an argument that you should always separate art from the artist. The idea is that art should stand on its own two feet – that if you have to know something about the artist, or consider their intent or biography to really understand what they’ve produced, then there’s something wrong with the art itself. Equally, that protects the art: someone could be a terrible bully, unfaithful or abusive even – but if they wrote, say, a great love song, should the song be diminished by their private life?

No-one’s asking for Tyler to be cancelled, no-one’s even saying he broke the law (here in the UK, a 25 year old can legally have sex with a 16 year old, and in several states in the US it’s legal too). Maybe he just fell in love with the wrong person and “the heart wants what the heart wants”? He had the consent of her parents and intended to marry her. You could argue that it has nothing to do with Aerosmith’s music.

A newer strain of criticism argues that all art is the product of its time and that we have to consider the social context. That we can and should acknowledge the troubling sides of artists, and liking their art doesn’t mean that we have to exonerate their behaviour. The question then is maybe: does liking what they’ve produced make us complicit in their world view?

Does Walk This Way, with its lyrics about horny schoolgirls, written by a guy going out with a school-age girl, ask us to leer at schoolgirls? Is it the direct product of an era in which multiple 70s rock stars committed statutory rape by having sex with teenagers – where powerful men abused their status to exploit young and vulnerable women – and is it tainted by association?

Or is it just a dirty song with a great riff?

Listen to the podcast to hear what the team thought.

Classic Rock's podcast The 20 Million Club focuses on albums that have sold 20 million or more, with mini-pod The 20 Minute Club bringing focussing on singles released at the same time as the album. Listen now on Apple Podcasts and Spotify or anywhere you get podcasts. Subscribe to never miss an episode.