On the morning that Prog speaks to Rick Wakeman, the veteran keyboard player is in a very good mood and about as far removed from his ‘Grumpy Old Rick’ Twitter handle as is possible to imagine. The reason? “I’m going to get my [Covid vaccine] jab this morning,” he says with some enthusiasm. It’s also possible another reason the 71-year-old is so chipper is that he’s talking about the events of 1971, a year that saw his career coincidentally given a massive shot in the arm after joining Yes.

In February 1971, The Yes Album was released and, nine months later, Fragile: two remarkable albums representing the survival and arrival of a progressive rock institution. The first secured their future, protecting them from the whims of record label executives. The second was a new integrated unit marching in lockstep that defined their own destiny on their own terms. Both records were, in part, the result of a catalyst; two new members whose contributions brought about a decisive change. Both enabled Yes to finally slip into another league entirely after nearly three years of commercial stalemate and the looming threat of obscurity.

Taken together, those two albums last a little over 81 minutes and stand as a testament to tenacity, decisiveness, and a remarkable flowering of creativity. With them, the transition from earnest hopefuls to bona fide stars was achieved. Yes would soon be able to say goodbye to gigs at Portsmouth Poly and bask in FM Radio’s heavy rotation in sun-drenched California and beyond.

“It was a great period. A time of tour, record and tour some more… it was another level… everybody was playing in a way they’d never played before,” recalls Wakeman, an astonished tone animating his voice, as if he still can’t quite believe his luck.

“Being in a band is sometimes like being in a family, you know, you’re living cheek by jowl especially in the early days of the group, and plenty of bands have had problems dealing with each other possibly because it is that family thing,” says Yes’ first keyboard player, Tony Kaye, speaking from his home in Florida.

In any family, there will be times of joy, excitement, disappointments, and loss. Alongside the support, respect and regard between siblings, thorny rivalries may grow, some left unresolved, or even undeclared for decades. Resentment

for sleights, both real and imagined, unfurl in the undergrowth and along the branches of the family tree. Like some pernicious knotweed, they slowly choke the life, trust and joy out of their interactions.

Tony Kaye, reflecting on the band he helped to found in 1968 and which he first left in 1971, experienced all this, and probably more internecine adventures than he cares to remember or talk about. Yet Kaye’s enduring enthusiasm for the group is such that he returned to the family fold for 1983’s 90125 and once again in 2018 as a guest on the 50th anniversary tour.

Yes are now a firmly established musical dynasty with a fanbase broad and deep-pocketed enough to sustain two different groupings, not only in the late-80s with Yes versus AWBH but again around the 50th anniversary with Yes running alongside Yes Featuring Anderson Rabin Wakeman (aka ARW). None of that and none of what’s been achieved over the last five decades and more could have possible had it not been for Yes’ very own annus mirabilis in 1971. The events that made 1971 so vital to Yes’ success had their origins in the previous year, and even go back further back.

In truth, ‘overnight success’ doesn’t really exist. Yes had slogged away paying their dues in thankless support gigs including, most famously perhaps, Cream’s farewell concert at the Royal Albert Hall in November 1968. “I think we kind of took it in our stride,” says Kaye. “Obviously, it was a pretty big deal for the band. We certainly weren’t very popular at that time. I guess it was between our manager Roy Flynn and Robert Stigwood who managed Cream to swing that for the band. And of course, yes, it was a bit intimidating.”

Just how intimidating was seared into the then 19-year-old Bill Bruford’s memory after dropping a stick in the opening moments of their cover of Leonard Bernstein’s Something’s Coming from West Side Story. There, literally in the shadow of Ginger Baker’s huge Ludwig double bass drums, he lost his grip on his stick. “I can assure you, the sound of a drumstick clattering and rattling down over a bass drum to the hard wooden floor of a silent and packed Albert Hall is absolutely the loudest sound I shall ever hear,” he’d later write.

For Kaye, further embarrassments are brought to mind. He laughs when he remembers his early career. “I used to try and disguise my Vox Continental with a three-sided wooden plyboard stand that was laid around the front so it looked a little more like a Hammond. It was pretty bad,” he admits.

Although barely known beyond a rat run of college gigs and clubs, Yes were signed to Atlantic Records, which conferred both status and prestige on this band of hustlers living in communal near-penury. “Being on Atlantic lifted the band to another level,” agrees Kaye, relishing the freedom the band experienced in the making of the album. “I guess it was specific to that particular time that they kind of let us do whatever we wanted to do, you know? You don’t really see that anymore.”

Released in the summer of 1969, the band’s self-titled debut album was housed in a striking comic book speech bubble and delivered a simple but effective graphic impact. As Yes grew in stature, such illustrations would become more elaborate and, to some extent, echo the complexity of the music. Musically, the band could sometimes be heard punching above their weight and this established quite early on another aspect of their personality. Despite their winning formula, not enough people went out and bought the album and it failed to reach the UK Top 40. Fortunately in those days, that didn’t matter too much as record labels were often prepared to give bands longer to find out what worked best. For now, Atlantic were happy.

On their 1970 follow-up Time And A Word, Yes needed to try something else. Maintaining a steady-as-she-goes course wasn’t something that singer Jon Anderson was content with when it came to recording their second album. Not for nothing did Anderson pick up the nickname ‘Napoleon’ from his bandmates due to his small stature and autocratic tendencies. If their debut had been a good calling card for Yes the next album had to be better, Anderson argued. There was no point in treading water and simply repeating the formula that worked well enough the first time around. Adding an orchestra might help that process imbuing the songs with an added sparkle.

Recording sessions were grabbed in between gigs during the winter of 1969 and early 1970 at Advision Studios, but as the songs became upholstered with a string and brass trimming, guitarist Peter Banks was at odds with his colleagues over the direction. Personal differences between Banks and producer Tony Colton only increased the tension.

Used to being the centre of attention onstage, Banks’ misgivings about being sidelined in the studio were a source of grief. He felt the mix didn’t always pay him as much attention as he would have liked and, although he didn’t know it at the time, he was establishing a disputatious template that would accompany most of Yes’ album mixing sessions. In the years to come, individuals would variously demand more bass, more keyboards, more guitar, more drums, more voice, and, well, just more. Regardless of Banks’ displeasure with the finished album, there are plenty of moments where his thunder, far from being stolen, is well to the fore. The frantic free-falling solo during their inspired version of Buffalo Springfield’s Everydays, a cover that far outstrips the laconic original, demonstrates Banks’ brand of dazzling bravery that veers between frenzied excitement and reckless abandonment.

Yes have since garnered a reputation for being ruthless when dealing with personnel issues over the years, ousting members or managers with the ease by which one might slip off a burdensome overcoat that no longer fits. What do you do when someone in the band isn’t keen on the proposed direction? Most of the time that band will make compromises and accommodations to avoid conflict but when that doesn’t work, what then? Just two months after the completion of Time And A Word the answer to those questions came at the end of a gig in Luton on April 18, 1970. The band were backstage when Anderson and Squire told Banks he was out. Tony Kaye claims today that the precise reasons for Banks’ sacking in 1970 remain a mystery to him and that neither he nor Bruford was even aware it was coming.

“Pete was a top guitarist. He loved Pete Townshend and he loved that kind of extreme, loud rock’n’roll,” he recalls, “I recently saw some old videos of that time and both of us, we were pretty energetic… Pete was putting his guitar through the ceiling on certain club stages and just kind of doing a Townshend thing. I never really understood at the time why he was fired. It wasn’t really explained, but I guess in retrospect that had something to do with it: the band wanted something different I guess. Pete was not very enthusiastic about the orchestral addition and it was something that Jon was very into. And of course, the band went in that direction but it wasn’t really my direction either. I thought it was a good combo that the band had together at that time but it was not to be.”

Finding a suitable new guitarist wasn’t the only problem Yes were facing. Although Time And A Word had scraped in the lower end of the charts it hadn’t really made much of a difference to the band’s prospects. “There’d been nothing but big promises about how great we were going to be, but we were going round and round in ever-smaller circles. The gigs weren’t getting much better and we were running out of money. We were signed at the same time as Led Zeppelin and they were doing pretty well and King Crimson had this astonishing first album, we were just knocked backwards by that and jealous as heck. There we were in our little damp farmhouse with 50 quid [to our name]. That was two and half years or something into the band’s life and we’d singly failed to produce,” says Bruford summing up the prevailing mood.

Having a vision and acting upon it requires a significant degree of commitment. In parting company with Peter Banks so suddenly, so decisively, Yes had displayed a willingness to do whatever it would take to make that vision a reality. There wasn’t really any room for passengers. It was that simple.

“Bodast were a rockin’ band,” recalls Tony Kaye. “I’d seen Steve Howe playing with them probably on one of my visits to [London music venue] Speakeasy and I remember telling Chris and Jon I thought he would make a good replacement for Peter Banks.”

Kaye was right. In Steve Howe, they had found a guitarist who brought another level of technical skill and compositional flair to the group. However, perhaps most importantly of all, Howe wasn’t interested in any old gig to tide him over. “Basically, I was very hungry for success and extremely ambitious. I was 23 when I joined, so I guess I was in a new place because my son, Dylan, had just been born so that was really a kind of wake-up call. So I suddenly had so many reasons to want to give my best to my work, for my family really.”

Reasoning that he’d upped his game touring as part of PP Arnold’s backing band, where on the Delaney And Bonnie tour he’d rubbed shoulders with Eric Clapton and George Harrison, Howe was looking for a group that were equal to his ambition. In meeting Yes, he knew he’d found them. What he didn’t know was how precarious their future actually was.

Having decamped to Devon, the band initially sequestered themselves in a cottage but that proved unworkable. They received complaints from the neighbours who, understandably, weren’t so keen on the sound of the group reinventing themselves after nightfall, and the guys subsequently found themselves at Langley Farm, near South Molton and splendidly isolated.

Despite manager Roy Flynn visiting in the writing process to tell them he could no longer afford to keep bankrolling the band, thus bringing their association to an end, Yes’ creativity increased. Howe is sure the very surroundings had a significant impact.“It was very much like The Band,” Howe says. “One of the good things about going to the country is, of course, there are no distractions [unlike] working for, like, three hours in Soho or something and going, ‘Oh my God, I gotta get outta here!’”

Tony Kaye also has fond memories of the period and recalls the late-night journeys through tiny country lanes. “Steve and I used to go out and I used to drive around Devon. Steve and his guitar [would] create a lot of what eventually turned up on The Yes Album. Steve and I were pretty close at that time and a lot of good collaboration came out of it down there.”

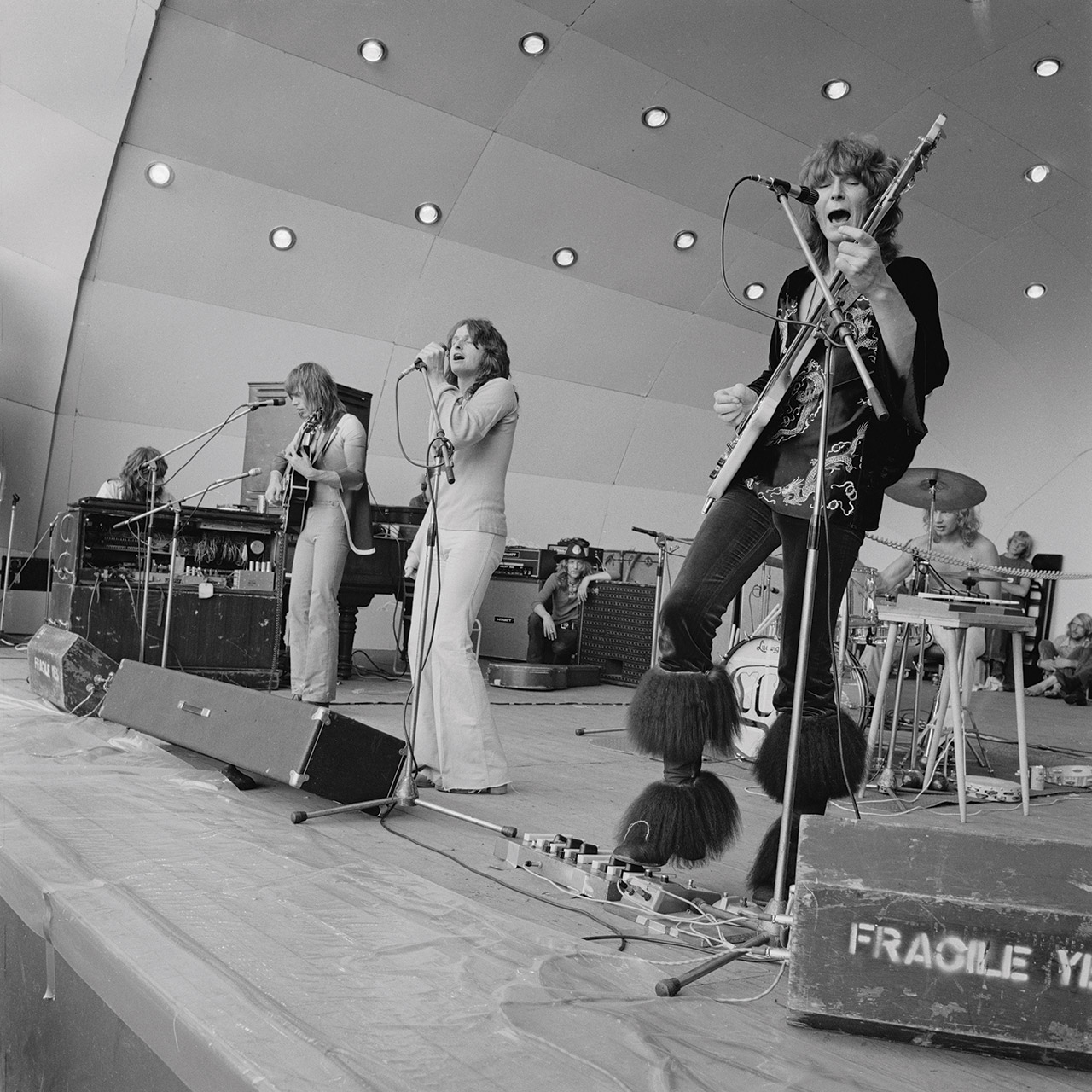

Almost from the off the new incarnation of the group caused a stir. The vigour and exuberant confidence was palpable. One person who was impressed was the keyboard player from support act Strawbs. “It was a show in Hull and after we’d done our set I went into the audience and watched Yes. It was an eye-opener,” Rick Wakeman recalls. “I’d never seen a drummer mic up all his drums before or tune them like Bill did. Most bass players used big Marshall stacks and played a Fender jazz bass. Chris came up with some amp that I’d never heard of and a Rickenbacker that was so out of fashion it was unbelievable. Then, there was Steve and when most guitarists were using Strats, Telecasters and big Marshall stacks, he had a couple of little Fender Twin amps and was playing a semi-acoustic Gibson. Most singers at that time were six-foot-three [with] long greasy hair and tenor voices, and on comes this diminutive little pixie, with an alto voice who looked tiny against Chris, Steve and Bill who were all six-footers. The only person that I suppose looked normal for a rock band was Tony Kaye, who had a Hammond organ. I was so knocked out with how they played, the arrangements, and their style. They bore no resemblance to anything else that was about at the time and I thought, ‘Shit, this is going to be

a great band.’”

It’s sobering to think they nearly went from a great band to being a late band. Instead of a career spanning more than half a century, 1971 could have been marked by the posthumous release of their third and final album. Driving themselves to and from gigs, and falling asleep at the wheel on the return journey was almost an occupational hazard. Bill Bruford recalls he often sat in the front maintaining a constant barrage of questions in order to keep Jon Anderson or Chris Squire from dozing off. After a show in Plymouth, having got as far as the outskirts of Basingstoke, their luck ran out.

“It was tough driving in all kinds of conditions up and down the M1 and everywhere,” Tony Kaye remembers. “We hit a truck head-on in the pouring rain. I was in the passenger seat, the rest of the band were in the back. It was a full-on impact and the engine of our vehicle was pushed back into the cabin and broke my foot. It was scary.” The accident left Kaye’s foot in plaster and the rest of the band treated for shock and minor injuries. The aftermath is captured on The Yes Album’s front cover, with the band having been released from the hospital that very morning.

“Everything was always just in the nick of time with Yes,” reflects Bruford. “We only just got to the gig in the nick of time, only just got a new manager in the nick of time, you know? It was all but over. People have forgotten just how critical a time it was then. We weren’t costing a lot – the rent of a house and a bit of food to keep body and soul together – but Roy Flynn had done that for a while, bless him, and we were in deep trouble.”

Naturally, says Bruford, the band were concerned, but sometimes in the face of such a crisis you find the reserves of courage and self-belief to turn the situation around. “It was really Jon Anderson who drove it, though. It was Jon who was always on the phone, always hustling gigs, it was Jon who managed to find [film production and distribution company] Hemdale, who were then employing Brian Lane. Brian was like a branch of the social services,” he says with a laugh. Lane’s influx of financial support enabled the band to grab time at Advision Studios. Lane’s background as a record plugger was also invaluable when it came to the release of the record.

“There’s another thing I remember about the release of The Yes Album, which was an incredibly serendipitous series of events,” he continues. “Between January and March 1971 there was a national postal strike, which meant that the Melody Maker chart had to be suspended because they weren’t getting the returns back from the shops to be able to compile a chart. Who should step into the breach but a young Richard Branson who had a chart and so the newspapers of the day started printing Richard Branson’s Virgin chart. The guy who owns the charts puts in what he wants. Brian Lane said he’d get us in the charts. People talk, a couple of hundred quid changes hands and before you know it, you’re in the charts. It’s that that got Yes going.”

Whatever dark deeds may have been indulged in, The Yes Album broke through at No.7. It was the first time a record by Yes had entered the UK Top 40 and it went on to reach No.4 in the Official UK Charts.

“Up until Yes, I’d known nothing but serious letdowns that I don’t even care to talk about; being left flat here, being turned down there, being accused of this here, being fired there, you know, losing out,” says Steve Howe from his home in Devon, in the very property where the band created The Yes Album just over 50 years ago. “So when I joined Yes it was all musically very exciting. Although I enjoyed cover versions, I couldn’t see a career being built out of them.”

Howe argued it was better to expend energy on original material rather than someone else’s songs. If that was true for The Yes Album it would certainly be true for the songs that would become part of their next album.

The success of their third album, released in February 1971, gave Yes the chance they were looking for. It was an opportunity they consolidated with live tours in Europe and, crucially, in June, their first North American tour supporting Jethro Tull. It was on that first date, in Edmonton in Canada, that Bruford recalls thinking, “At last, we’re in the right place.”

In those bracing times of survival and arrival that characterised 1971 for Yes, the continuing expectations surrounding musical growth and evolution meant there was no time to rest on their laurels. If anything, their first real taste of commercial success demanded that they press on, taking advantage of record company largesse to pursue their own artistic goals. Why do more of the same when you could do something you’d not previously tried? Tony Kaye, by his own admission, pushed back against Anderson’s continuing demands for a grander, broader sound primarily being generated by the keyboards: “It’s a fact that I love the Hammond and piano and I was a purist on that level. It’s been said that I didn’t want to use the Moog or Mellotron although, of course, I used both in Badger [Kaye’s first post-Yes venture]. I was very concerned that keeping either of those two instruments in tune was a problem. The sound of the Mellotron trying to emulate orchestral strings was a little bit biting for me. The Moog was the beginning of a lot of things of course, and it wasn’t that I was completely against using them, but it’s true they were not my favourite instruments.”

Steve Howe still admires Kaye’s dedication: “Listen, I’ve got to say, Tony is such a great player. On the first three albums, he’s the only player who could have done that stuff. He plays some absolutely brilliant things but we were we already going to go hell for leather wanting to get all the textures and be this kind of orchestral sort of group. So when the idea came that there was someone more versatile and willing, that’s where we went.”

Kaye played his last gig with Yes on July 31, 1971 at the Crystal Palace Bowl. It was just over a year since Peter Banks’ departure, although he’d return to the Yes family some 11 years later.

Yes knew exactly who to call in order to supply the kinds of textural sounds they were so keen for the newly emerging music to include. In an interview with journalist Penny Valentine in 1970, Wakeman had bemoaned the state of keyboards, particularly the use of piano and organ onstage, citing Keith Emerson and Tony Kaye as the only two in the field who were truly exploring the organ’s possibilities. “I have always tried to play something nobody else can play, I think I’ve based all my organ work on that kind of attitude,” he told the journalist. Some 50 years on he’s sure that Yes had seen the interview and marked him out as a person of interest. When the call did eventually come from Chris Squire asking if he’d like to come along to a rehearsal, it was at 2am, and an exhausted Wakeman, who’d just rolled into bed after a long recording session, firmly and unambiguously said, “No!”

Having already decided to leave Strawbs and go back to session work he wasn’t interested in joining another band. But having seen Yes previously and liked their material, he decided to go along to a rehearsal and see what they were up to. Where’s the harm, he thought… it might even be fun. It was interesting, he says, because he’d never worked on a song the way Yes did. In Strawbs, Dave Cousins would usually supply a song more or less complete, with only the arrangement to be worked on by the band. With Yes, things were very different, he says.

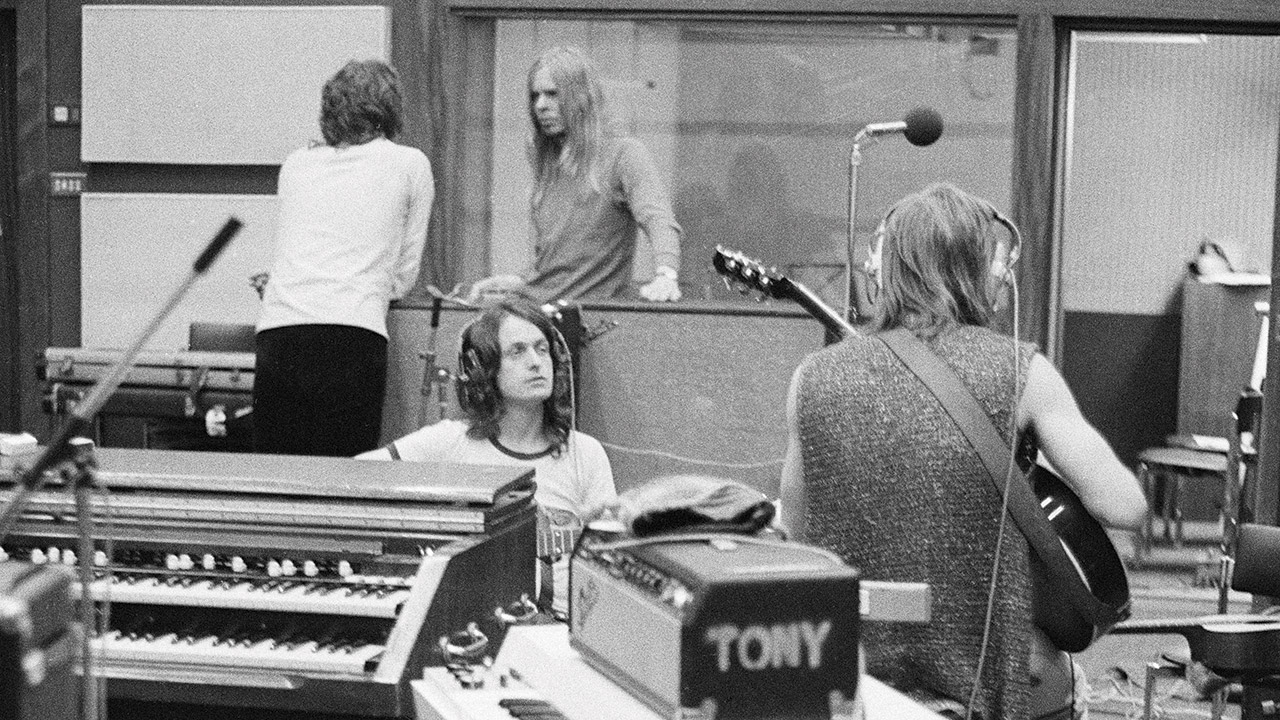

“I can remember, for example, Chris coming in and he’d been listening to King Crimson’s 21st Century Schizoid Man in his car on the way up. He said, ‘You know, I’ve been working on an idea for a bassline’, and he played the line that opens Heart Of The Sunrise but that was it. I thought, ‘What’s that all about?’ Then Steve said, ‘Does it work coming down the other way?’ Which he did. Then Chris said, ‘Well, what about if we go up another octave?’ So, I said, ‘Well, what if I come down while you lot are going up?’ And so we spent about an hour working on all the different ways that we could do this run, which was really interesting and with different sounds and Bill working on different patterns that he could do with it. I thought it was fascinating. We spent two or three hours doing that, and then after we’d done it loads and loads and loads of times, I think Jon said, ‘Well, what do we do? What’s next then?’ Steve had that line, so we put that together and shoved that on the end the whole thing started building around that. I came up with the weird chords that sort of come up underneath it, which became the chords for the song. By the end of the day, we’d put 60 per cent of Heart Of The Sunrise together. I thought this was absolutely fantastic!”

At the end of an enjoyable day Wakeman still hadn’t intended to join the group but after giving Howe a lift home, without thinking, Howe asked if Rick could pick him up at 10 the next morning. “So I picked him up at 10 the next morning and we just carried on like that. Roundabout appeared in the same way. All the things for Fragile were done that way. It was quite an eye-opener and very exciting.”

Without intending to, Rick Wakeman had apparently joined another group and he went on to play a key role on Yes’ fourth album, Fragile.

When Steve Howe closes his eyes today, he can still see small cameos from all the years he spent in Advision Studios, especially in relation to the making of Fragile. Some of those mental snapshots he carries from a lifetime spent within such cloistered spaces include: the control room, with the ever-present engineer, Eddie Offord at the controls; being sat in a broad semicircle in the large studio where they spent so much time, often from the middle of the afternoon and on into the early hours. He also recalls looking through the window of the separation booth as Jon Anderson sang, choosing which guitar to add to a track, and Bill Bruford attempting to conduct the band.

Bruford’s suggestion for the album was that each individual member of the band would take responsibility for the musical direction of a particular track, in effect becoming the ‘conductor’ of an ‘orchestra’ comprising the other members of the group. You can hear elements of it on Bruford’s Five Per Cent For Nothing and to a lesser extent, Chris Squire’s solo in The Fish (Schindleria Praematurus), but Howe, Anderson, and Wakeman took the chance to make their own distinctive solo statements.

“I saw my natural step as doing Mood For A Day,” explains Howe. "Rick and Jon also kind of did their own thing. That’s what makes Five Per Cent For Nothing so perfect because that was really where Bill was heading. Things like my solo and Rick’s solo, in a way, make Fragile about those steep, steep contrasts.”

Mired in a tangle of contractual problems, Wakeman was prevented from adding his own composition. Instead, he opted for a copyright-free arrangement of the third movement of Brahms’ Fourth Symphony. Having only monophonic synthesisers, he spent hours painstakingly building up the electronic textures and layering within the piece, not unlike Wendy Carlos’ Switched-On Bach pieces. “So of course you had your headphones on listening to the track while you put the next bit on it. It took ages on the days in the studio when I was doing it. It was probably it was Bill who would say ‘Oh, I think Rick’s doing cans and Brahms.’”

Despite being a full member at the time, Wakeman received no writing credits for contributions such as the extended piano suite that makes South Side Of The Sky so effective in its use of space and dynamic colour because of those publishing wrangles. “You didn’t stop to fight about it with management because that would have held things up, and you were so keen just being there. They said it would all get sorted out and I’d get my writing credits but I never did,” he laughs ruefully.

As the ‘new boy’ of the band Wakeman observed the interactions and roles within the group and their outcomes within the emergent music. “Bill was fantastic and worked so closely with Chris Squire. They argued fiercely, but what they came up with, the two of them playing together… I don’t think I’ve ever worked with a drum/bass combination quite as incredible as Bill and Chris. The outcome was just always sensational. Steve played guitar like nobody else I’d ever known. He just had a completely different sound to everybody I’d ever played with. He played in a different way and it was quite incredible and inspiring because it left a lot of gaps for me to put things in and do things, which was fantastic.”

Bill Bruford once observed that one of the best musicians he’d worked with was Jon Anderson, despite the fact the singer had little in the way of instrumental technique. Wakeman agrees with his judgement: “Jon was a musician in his head and that’s something quite unique. He could hear things but he needed a band to get them across. It worked really well if you had the right line-up to do it. It was like, I suppose, five architects in the same room trying to build one amazing building.”

Assiduously crafting songs from a disparate collection of runs, riffs, fragments, rhythmic patterns and other musical bricolage isn’t easy or quick, yet the sessions for Fragile were incredibly productive. Sometimes emerging themes received attention but never quite landed. Some of the ideas created during Fragile would later be recycled as Siberian Khatru and The Revealing Science Of God. The ones that did make it to the final album stand as classics in the Yes catalogue, with Roundabout and Heart Of The Sunrise, being particularly outstanding. Listening to them is akin to witnessing an intricate mechanism, each cog and wheel interlocking to propel the various movements and sections. Bruford’s sturdy yet always elegant drumming; Chris Squire’s brightly lit, rasping bass; Wakeman’s dramatic keyboards; Howe’s intricate honeycomb of tones and texture; and Anderson’s soaring vocals all added up to something that was substantial, authoritative and original. In the beginning, Yes had sounded like one of many bands out in the field. But just nine months after the release of The Yes Album, and with Fragile now under their belt, it was clear that nobody else sounded like Yes.

Howe recalls the buzz of excitement on the first playback of a freshly minted test pressing of Fragile in the studios. “Somebody brought a sound system down from upstairs. I remember the first time I heard The Yes Album on a test pressing there, I thought we sounded weird, even to me. But when Roundabout got going when we first heard [Fragile], I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is tight!’ I could hear the harmonics and the vocal harmonies and I thought, ‘Jesus Christ this sounds really good!’ I could revel in it for a second and say this is really good.”

Wakeman believes that Fragile worked so well because of the commitment each of them had to each other playing at a level they’d not previously achieved. Nevertheless, the degree of success initially took them all by surprise. “I remember being in [the US] before it came out in England and we started getting messages that it was selling incredibly well. We went, ‘Oh, really?’ and we sort of came home to find we’d got a hit album.”

Howe says they were acutely aware that this was their moment. “The second time we went back with Fragile we told Atlantic to really get behind it while we were out on tour. We had that self-belief and confidence because music will give you that. We really liked it, really believed in it. I mean, we liked The Yes Album quite a bit as well, but at that time Fragile took things to another level.”

Bill Bruford recalls being somewhat taken aback by the way Roundabout suddenly became the track that every DJ wanted to play when he returned to the States, and by association, just how successful the band was. “You could laze by the pool on the top of the Sheraton Manhattan and hear it on WNEW-FM every 45 minutes. My world was all ‘heavy rotation’ and Billboard placings interlaced with enormous salads and suntans. Much more of that and I would have turned into a rock star.”

Fragile was the first album by Yes to go in the US chart at No.4, eventually going Platinum in the UK and double-Platinum in the US. It’s remarkable just how commercially successful Yes’ 1971 albums were. Their songs were mostly complex and their lyrics anything but straightforward – even the man responsible for writing them admits they defy any definitive interpretation. In fact, when Jon Anderson sang, ‘You’ll see perpetual change’ it wasn’t just a line from a song; it was a manifesto for

the new Yes and a state of revolution that began with The Yes Album and continued through a run of releases that constantly upped the band’s game and sometimes even tested fans’ patience to the limit.

The Yes Album and Fragile completely transformed the fortunes of the group but in an alternative universe, had The Yes Album failed to sell Yes would have been dropped. What would have happened then? Would another label have taken up their cause? Perhaps they would have broken up and gone their separate ways? Maybe even the passing of a few decades would have burnished their three albums with a cultish gleam as they became the stuff of collectors’ dreams, mint copies going for more cash than the band ever earned for doing a gig?

Back in the real world, things got increasingly surreal. Bruford, Howe and Wakeman all agree that the band’s artwork was a key part of the change in how Yes were perceived. If the mysterious, urban confinement of The Yes Album’s cover belied the pastoral surroundings of its creation, Fragile took them to a very different space; albeit one that was remarkably in simpatico with its contents. Roger Dean’s artwork might have been seen gracing the covers of other artists of the day – namely Osibisa – but the deeper symbiosis between the worlds he was creating on canvas was most securely rooted in Yes’ albums.

“Roger’s work for the band was amazing,” says Wakeman. “We felt it reflected the music. You look at it and say, ‘That’s Yes!’ When we first saw the cover to Fragile we all went, ‘That’s it!’ Roger was the artistic sixth member of the band in the same way that George Martin was the fifth Beatle.”

Howe emphatically agrees: “Fragile set such a high standard. Bang! There

it was. It felt like it was ours as much as Roger’s. I mean, we didn’t design it but we kind of adapted Roger’s works into our music. It’s amazing how tight the two entities are.”

Whether you’ve rolled a joint on it or not, gazing at the mysterious world of Roger Dean’s art is illuminating. In those sparsely populated and gravity defying worlds, mountains really did come out of the sky and stand there. If the cover was a multicoloured fantasy then the music had a cinematic echo in its pristine, beautifully crafted sonic clarity. Suddenly Yes albums didn’t only look great, they sounded great too.

As the band’s momentum increased and the conceptual ideas got bigger, their albums took on lives of their own, becoming voracious monsters greedily living almost exclusively on precious metals of silver, gold and platinum. Concert halls grew in tandem, eventually only arenas would do. And when those weren’t big enough, stadiums were added in order to accommodate the hordes after a hot ticket. The unstoppable gush of income gave their accountants three-day migraines as they tried to tot it all up. Band management and record label executives became minor potentates. Even once-broke ex-managers got to dine on the royalty overrides and other contractual crumbs that fell from the groaning table. And the members of the band? Success of this magnitude ripples like an unseen gravity field affecting those under its influence in profound, unpredictable ways. They had the freedom to do whatever they wanted and they did it. But where once individuals worked closely, over time, in these strange and rarified times they grow apart. Closeness replaced by distance. And sometimes, a sharp distance at that.

Howe reminisces over the first rehearsals as the band made Fragile. “They were very special times because, although we didn’t know it, it became harder and harder to create that kind of environment. In other words, the rehearsals that were inspiring were the ones where we were all in the right frame of mind, where somebody has an idea and we didn’t chuck it out because we didn’t like it. We said, ‘Well, there’s something in there, what’s going on? Show us it.’ They’d show you the tune and you’d work things in around it.”

Working with goodwill and able to compromise, and see a piece possibly go off in a direction they hadn’t anticipated can be incredibly creative but it takes time, he says. “All the difficulties you might encounter along the way in that process are essential to the outcome of there being an album. If you’re going to accept a wishy-washy outcome then you can just float along with it but being in a band is about ideas… It can be tough. It’s about making decisions when it comes down to it.”

This article originally appeared in issue 118 of Prog Magazine.