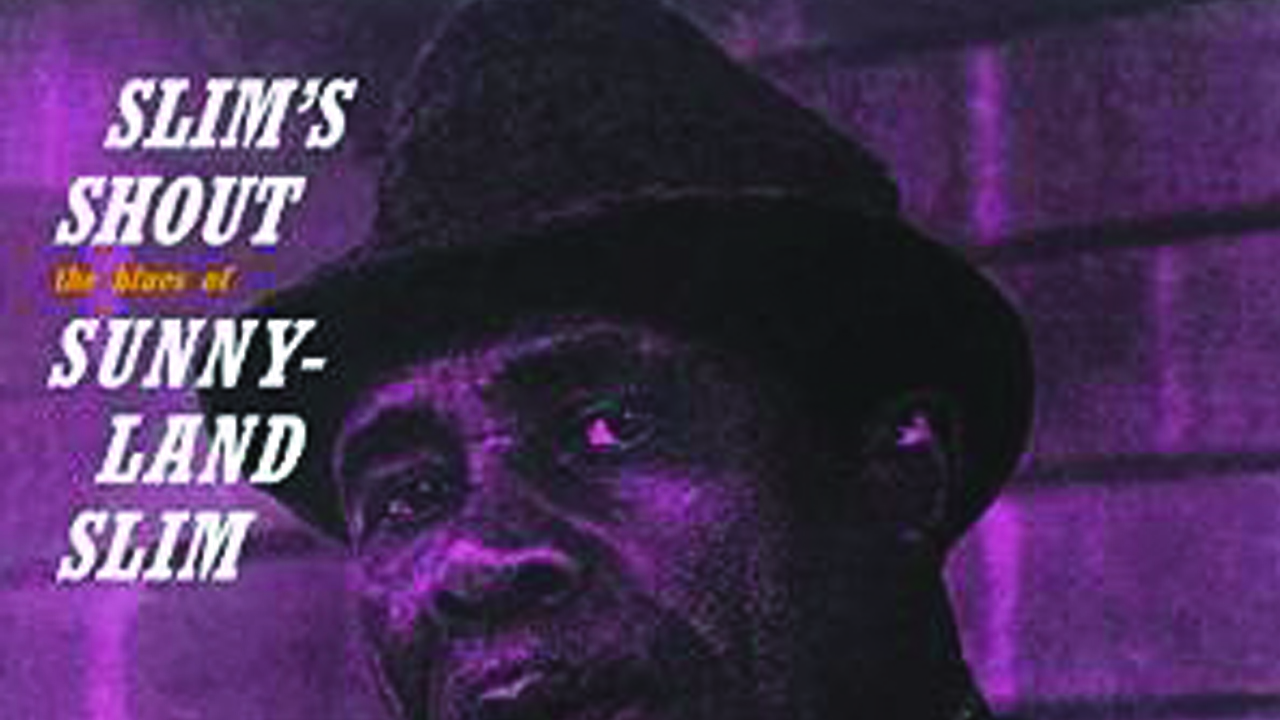

Two sets from 1960 featuring the most solid pianist in Chicago.

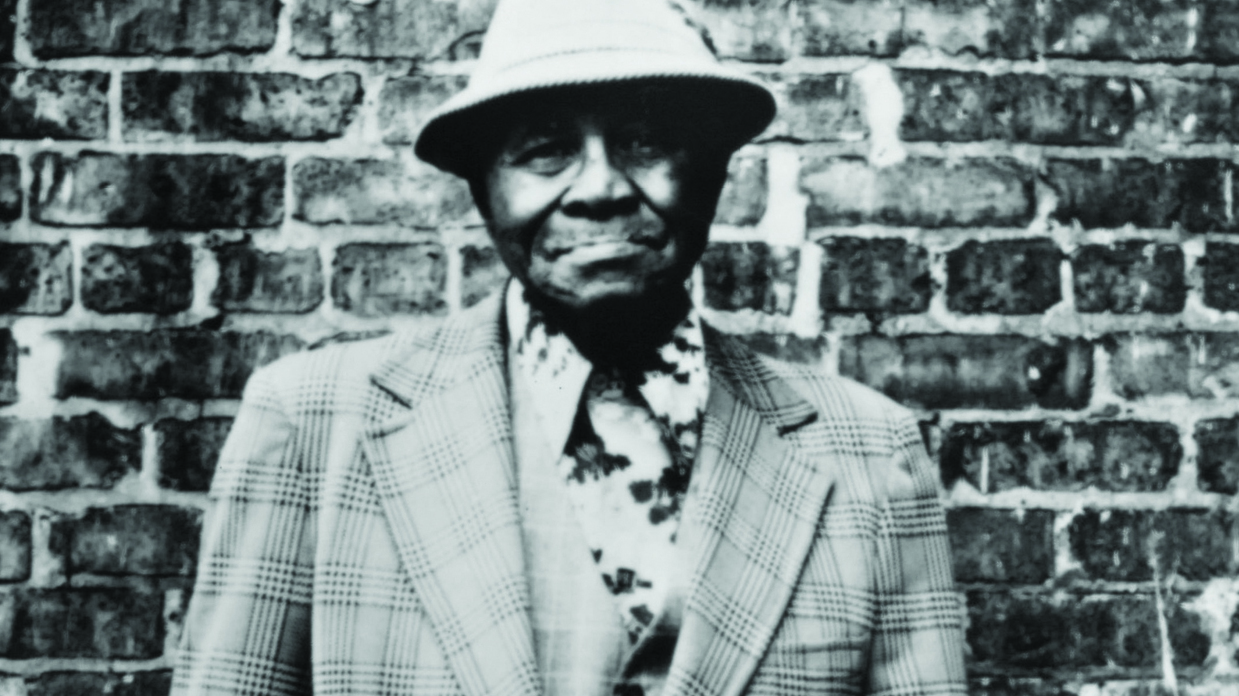

SUNNYLAND SLIM WAS a meat-and-potatoes bluesman. The dish he served up was plain, but it was always well-cooked and sustaining. His method was very much that of Roosevelt Sykes or Memphis Slim: assertive singing, forthright piano playing. When he came to make Slim’s Shout, his first album, done for the Prestige–Bluesville catalogue, he had several decades of playing behind him, much of it in noisy clubs and bars where a musician had to be loud to be heard.

Slim had been making records since the late 40s, so a studio held no mysteries for him. He was used to accompanists, too. Early in its life, Bluesville tended to wheel in studio musicians whether they were compatible with the featured artist or not; Roosevelt Sykes’ first LP for the label was ruined by poor players, and on his second date, in September 1960, he must have been relieved to find a decent rhythm section provided. Slim came into the studio the following day to work with the same players: King Curtis on tenor sax, Robert Banks (organ), Leonard Gaskin (bass) and Belton Evans (drums).

Banks’ organ playing was a hazard for some Bluesville artists, who struggled to extricate themselves from its molasses-like folds. Slim was not a man to be hampered like that, but Banks does take up a good deal of space that the pianist could have filled perfectly well himself. Curtis, however, was a sideman anyone would welcome, especially when playing the graceful intro to Decoration Day. He sits a couple of numbers out, one of them the very funny Harlem Can’t Be Heaven, Slim’s version of his friend Doctor Clayton’s Angels In Harlem.

Slim carried a folio of personal standards such as Prison Bound, The Devil Is A Busy Man and Brownskin Woman. All of these appear both on the Bluesville album and on the other LP reissued here. Also studio-recorded, two months earlier than Slim’s Shout, Chicago Blues Session was supervised by the English blues historian Paul Oliver, one of the many landmarks on a now almost legendary 1960 field trip.

What Soul Jam don’t make as clear as they might have done is that this LP – originally issued on 77, the label of Dobell’s Jazz Record Shop on London’s Charing Cross Road – is a double showcase for Slim and his contemporary Little Brother Montgomery, who has five tracks (out of a dozen) of his own and also plays behind Slim on a couple. This is no hardship for the listener, since Montgomery was a pianist of great range and ability, and his solo Trembling Blues is a thing of beauty. He, too, had his standards, like That’s Why I Keep Drinkin’ and No Special Rider Blues, but these are upstaged by his extremely odd composition My Electrical Invention Blues.

This collection finds both men on a little less than top form, and Chicago Blues Session has some small technical flaws. Having said that, these are two decent albums worthy of their makers, and they are both very welcome back in catalogue.