The sixth annual London BluesFest gets off to an emotional start. “This is a dream come true,” says Imelda May as she wraps up her guest appearance with Bill Wyman’s Rhythm Kings with a storming version of the Animals hit I’m Crying. “A lot of gigs you do, people might not chat so much,” she says. “But backstage tonight it’s a great bloody party!”

She’s not joking. Wyman’s Friday night fandango at the Indigo stage is an upbeat celebration of the bass player’s 80th birthday (“I think I’ll be eighty again,” Bill tells us later, “and have another one”), a landmark that would have been barely conceivable when the Rolling Stones were laying the foundations of the British blues scene that flourishes to this day. The show is an affectionate trawl through the history of both Wyman and the blues music he’s loved all his long life.

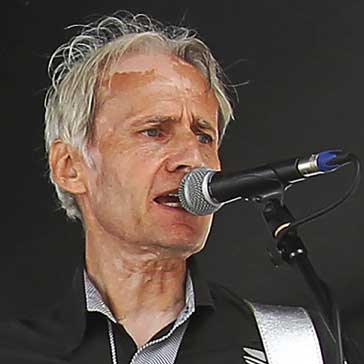

It begins with Joe Brown, who dedicates Summertime Blues to all the old Teddy boys. “One of the saddest things I’ve seen is a bald Teddy boy,” Brown, 75, says to much hilarity. Minutes later, a notably clean-headed Mark Knopfler, 67, arrives on stage. “It’s great being the youngest here,” he says, looking pointedly at Brown, before launching into the leisurely slide guitar shuffle of Donegan’s Gone.

Van Morrison steals the first half of the show with a stupendous rendition of the Ray Charles song I’m Movin’ On. As well as measuring out the words in his most soulful bark, Morrison bestows an ultra-cool saxophone intro and solo on the song. “I think I’m going to wet myself,” says the woman behind me.

Bob Geldof, a willowy, white-haired, surrogate Jagger, sings Little Red Rooster and Route 66, accompanied by Little Steven Van Zandt on guitar. Van Zandt presents Wyman with a BluesFest Lifetime Achievement Award and the show ends with a burst of 1950s rock’n’roll deluxe from the mighty Robert Plant, brilliantly accompanied by Imelda May. The whole cast joins in for a final chorus of Happy Birthday.

At the aftershow gathering in the bar upstairs, Plant, Geldof and Mick Hucknall are among the many stars circulating the room, high-fiving and air-kissing everyone in sight. Wyman confesses to having been brought close to tears by the outpouring of so much goodwill. “Same again for your ninetieth then Bill?” says one punter as the night winds up, making him chuckle.

Backstage on Saturday, festival director Leo Green adds a long slug of honey to a giant cup of tea, while constantly parrying text messages and calls on his mobile. Green started the festival in 2011 at several modestly sized West London venues when the bill-toppers were BB King and Liza Minnelli, and ticket sales totalled about 14,000. Last year it was at the O2 and sales were about 40,000. This year’s festival is the biggest yet.

“It’s always been a blues, jazz and soul festival,” Green says. “I suppose it’s become a roots festival, really. I’m not out to redefine what blues is. It has to be a broad church. And we have to adapt our line-up to who’s touring when. We originally timed it for this week because it’s half-term and I really wanted to include kids. When I was a kid, I remember being taken to the Capital Jazz Festival and loving it. And there were kids in here last night, with their parents. I just want it to be inclusive.”

For some hard-core fans, however, having acts such as Mary J Blige and Maxwell headlining on Friday night in the main arena is a little too inclusive. “I saw people on Facebook saying some of these acts are not blues,” says Walter Trout, who has played every blues gig known to man, and a few more besides. “That to me is just the regular blues snobs who have their head up their ass and don’t realise ‘the blues’ is a big tent – like this venue.

“I think the BluesFest is doing a fucking great job of flying the flag for the blues,” Trout adds. “I think the line‑up this year is incredible. I didn’t see any bullshit acts on there. Kanye West isn’t here. You know what I mean? The blues could do with some good news as well. I was real sorry to see The Blues magazine recently closed down because, like BluesFest, the great thing about that magazine, it wasn’t all just Buddy Guy, Muddy Waters and Eric Clapton. It did a lot for the up-and-coming artists. The young ones trying to get somewhere. They were always in there. What a great publication. I loved it.”

Over on the Arena stage on Saturday night, Richie Sambora is huffing and puffing his way through a set of pop-rock standards on steroids. Singing and playing a Stratocaster that looks as battered as he does, and assisted by his musical and romantic partner Orianthi, also on guitar and vocals, he bangs out Bon Jovi favourites Wanted Dead Or Alive and Lay Your Hands On Me before the couple lurch into an ill-conceived duet of the Sonny & Cher hit I Got You Babe. In a gallant display of New Jersey-boy solidarity, the ubiquitous Steven Van Zandt arrives to save the day. Too late, however, he discovers that he doesn’t know the words to Livin’ On A Prayer and the show ends with a cheerful but painfully unrehearsed flourish.

- Richie Sambora – “I was the guy trying to stick the blues into pop music"

- The Best Of BluesFest

- The best new blues albums you can buy this month

- 2016, The Ultimate Playlist: Bluesers & Shakers

Nothing about Bad Company’s performance is remotely unrehearsed or left to chance. They aren’t a band given to springing surprises, and the most unexpected thing about their set is a version of the rarely played Crazy Circles, an acoustic, neo-folk song from the Desolation Angels album. But boy, do these guys know how to dish out perfectly calibrated, arena-strength blues-rock anthems. The immaculate pacing and rock steady groove of Feel Like Making Love, Run With The Pack and Ready For Love is simply irresistible. Can’t Get Enough indeed!

While Bad Company are holding court on the big stage, an extraordinary scene is unfolding over at the Indigo. the Marcus King Band, led by a 20-year-old wunderkind from South Carolina in a 10-gallon, Stevie Ray Vaughan-style Stetson, is putting on a jaw-dropping display of shredding, hollering, ultra-boogie in excelsis. “We’re known as a psychedelic, southern rock, jazz-fusion, blues, whatever band,” King tells me when I run into him later, backstage. “It’s a bit of an eclectic vibe. The blues is the main root. A lot of my family live around the Blue Ridge Mountains. When I was a kid my great-grandfather, my grandfather, my father, my aunt, we’d all play on the front porch. There’s a sense of community. Making music was a joyous, family thing. A natural form of expression.”

The Marcus King Band, which includes horns, keyboards and a killer rhythm section, have something of the free-flowing yet highly technical vibe of the Hot Rats-era Frank Zappa, an impression bolstered by King’s perpetual-motion soloing style. His singing is just as huge – a kind of sore-throat gospel yell. It’s not quite clear how he pulls it off, but on his first visit to the UK, King is the only act over the entire weekend to be allocated two sets. What’s more, he’s worth it. Look out for this dude.

Meanwhile, over in the Brooklyn Bowl, Jo Harman is seducing an audience of barflies who hang on every word of her epic ballads of romantic joy and despair. Her version of Michael McDonald’s I Can Let Go Now sends a tremor around the room. ‘The pain and ache a heart can take/No one really knows…’ she sings, her voice freighted with an eerie, hyperreal emotional payload. Now we know what becomes of the broken-hearted: they’ve all gone to see Jo Harman.

Sometime after 11pm, the London radio broadcaster Robert Elms steps out onto the Indigo stage and introduces: “The man with the band… around his head.” The curtains part to reveal the swashbuckling figure of Little Steven – head swathed in the inevitable bandana – leading his Disciples Of Soul. The 12-man band plus three-woman vocal section are a mixture of American and British musicians assembled with the help of festival director Leo Green, who it transpires has also blagged himself a gig as the tenor sax player in the Disciples’ horn section. “Little Steven phoned and said he could only do the gig if he could get a UK horn section,” Green explains earlier. “I said, ‘Leave it to me. I’ll sort it out.’ What an honour!”

Indeed, it’s almost entirely due to Green’s personal encouragement and involvement that Van Zandt is performing his first Soul Disciples gig in the UK for 27 years. ‘Historic’ barely does justice to the resulting two-hour show. Kicking off with Soulfire and an insanely propulsive version of Howlin’ Wolf’s Killing Floor (à la the Electric Flag), Van Zandt leads the band through a slew of songs from the golden era of New Jersey rock, blues and soul with a buccaneering swagger that’s second to none.

As well as reviving a whole bunch of Southside Johnny And The Asbury Jukes songs (All I Needed Was You, She Got Me Where She Wants Me, Some Things Just Don’t Change), Van Zandt also digs deep into the blues heritage with versions of Etta James’s The Blues Is My Business and Paul Butterfield’s Love Disease. Richie Sambora shows up at the end and together they stagger through Can I Get A Witness, like two old friends coming home from the best night out on the tiles ever.

While most of the action at BluesFest takes place on the venue stages in the evening, there are additional free ‘pop-up’ stages around the O2 complex where acts play short sets during the day to appreciative audiences of passers-by. One of them, entertaining the crowds milling around the BB King stage on Sunday afternoon is Kaz Hawkins, a crazy blues mama from Belfast with “a lot of ex-boyfriends” to sing about. She’s followed by Catfish, the London blues band led by the father and son combination of Paul and Matt Long, who deliver a fiery blend of post-Bonamassa blues rock.

It’s part of the BluesFest ethos to encourage impromptu collaborations. Indeed, hardly a gig has gone by without Little Steven showing up at some point, ready to rock. As part of this tradition, one of the revelations of last year’s BluesFest was the on-stage collaboration between Van Morrison and Tom Jones, who together played a set of blues standards and favourites, and revealed a shared history as buddies from the 1960s. Who knew? However, anyone expecting a rerun of the old pals’ act between Morrison and his co-headliner this year on the main stage, Jeff Beck, is in for a disappointment.

Beck starts the evening with a display of his samurai jazz-rock that’s by turns thunderously aggressive and achingly tender. Still the go-to virtuoso of the scene, he veers from the incredible melodic beauty of Goodbye Pork Pie Hat to the brute sonic assault of Big Block. The musicianship is beyond exceptional. But while Beck retains an aura of untouchable cool, Mr Conviviality he is not.

The stage is transformed from sleek, hi-tech emptiness to something resembling an intimate club gig as Van Morrison’s band’s equipment is rolled into a tight huddle in the middle. The sound is quiet, simple and warm, and the venue becomes an arena-sized supper club as the recently ennobled Belfast cowboy launches into a set of favourites including Baby Please Don’t Go, Cleaning Windows and a super-sleek, freshly updated arrangement of Moondance.

Morrison has already started a version of Call It Stormy Monday with a guesting Chris Farlowe when Beck shows up for their much-vaunted collaboration. It takes Morrison a while to notice him there, and then it’s all fixed smiles and a slightly stilted bonhomie as they wade through the familiar sequence. Beck is gone before the last chord has died out and that’s your lot. Getting the two together is a nice touch, but as these collaborations go, it’s a bit of a non-event.

It falls to Walter Trout to bring the curtain down on BluesFest 2016 with an undiluted shot of the hard stuff. His story of survival against the odds has been well documented and he’s well placed to play the role of last man standing. He gives a passionate and informed speech on the importance of signing up to donate your vital organs after death. Trout’s guitar looks in need of some sort of a transplant by the time he’s finished wringing its neck to produce volcanic solos in The Blues Came Callin’ and Goin’ Down. Now that’s what I call the blues.

Can there be such a thing as ‘real blues’ in the 21st century?