Alan Parsons Art And Science Of Sound Recording: Alan Parsons & Julian Colbeck / The Great British Recording Studios: Howard Massey

These are both important books, necessary documents that appear a decade into the on-going demise of the big recording studio. There’s already developing an almost mythic appreciation for old, analogue recorded music, and the studios and techniques employed that made it sound so good.

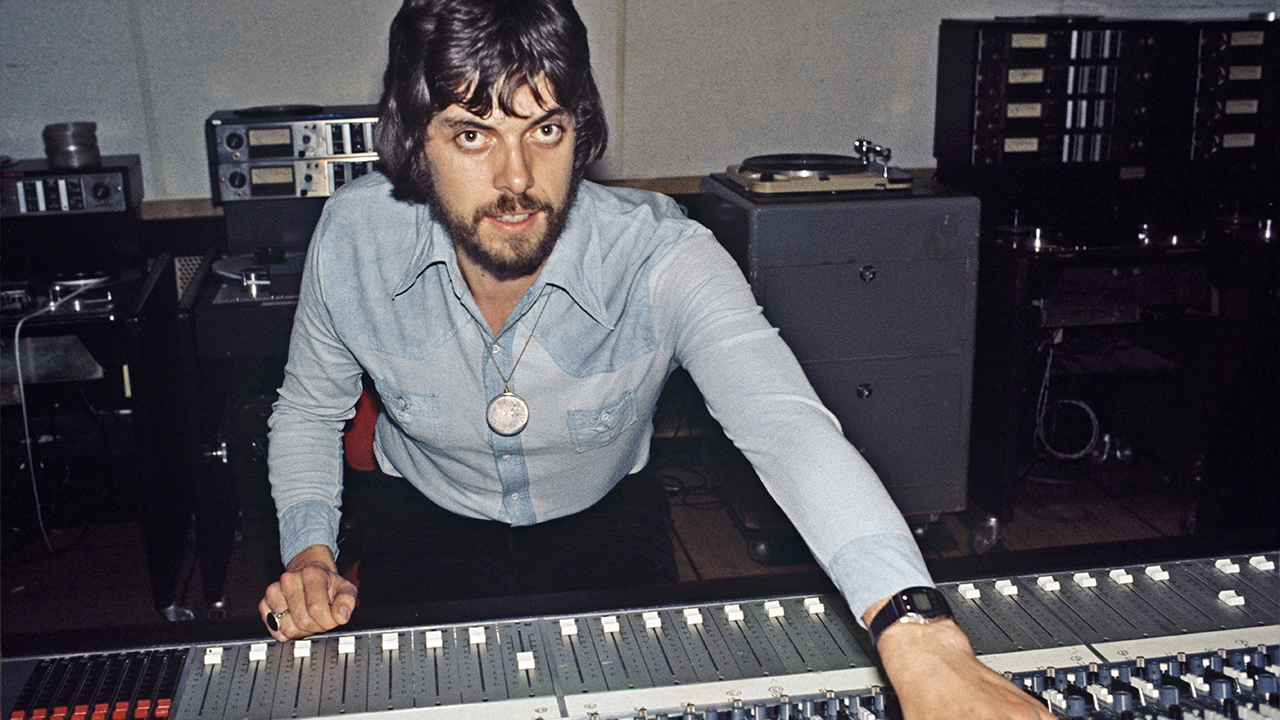

Yet, even as these weighty tomes arrive to indulge in romantic nostalgia for the analogue empire’s not-so-far off heyday, its destruction’s almost complete, a situation underlined at the outset of Alan Parsons’ (7⁄10) book: “Unfortunately, only a handful of large studios exist today. Which makes it very difficult for a young engineer to get the experience I had.”

Today there are literally hundreds of thousands of kids studying recording technology in the UK alone. It’s big business, despite the ironic reality that there are no longer any large recording studios with jobs left.

Parsons’ book attempts to bridge the gap between the retro-engineering style of guys who’d record opera one day, the Stones or Floyd the next, and the academic techniques taught today; to condense all that experience and technical know-how into a single book, designed and marketed at a potentially huge new student market. Largely impossible, of course, but he does reveal many of his favourite techniques, useful information for the budding bedroom-based laptop producer (the book accompanies a more in-depth video series).

I, meanwhile, find it fascinating. Many engineers are famously reticent when it comes to revealing their magic tricks and techniques, so it’s great to see Alan Dark Side Of The Moon Parsons, a titan of the recording world, reveal his secrets. Although I’m sure most readers can do without knowing how to make your drums sound like Bon Jovi’s.

Howard Massey’s extensively researched The Great British Recording Studios (10⁄10) splices dry tech specs with great personal stories to good effect, and is the only book I’ve seen that documents the pioneering days of British studios. I immediately skipped to the chapter on Olympic Studios where I worked flat out for most of the 90s. Designed by the visionary Keith Grant, Olympic was the 90s studio, far more formidable than ‘Shabby Road’. Not just for maintenance, but also kit, staff and, most importantly, vibe.

Massey laments Grant’s dismay after Virgin briefly took it over and redesigned it in 87. Refurbished by Terry Ottley (who coincidentally built my Space Mountain studio in Spain), the revamp had Sam Toyoshima design across all three studios. Unparalleled today, with a combination of super-large Genelix speakers and SSL consoles, this design defined the next decade of state-of-the-art recording, as tape was rapidly replaced, first with digital tape and then HD. In an ideal world the design should have remained unchanged, if only for posterity, but studios have always been very competitive and artists talk with their feet (as exemplified when the Beatles left Abbey Road for Trident as they were the first to upgrade to 16-track).

Massey’s research is incredible. He’s spoken to all the significant players, and TGBRS is packed with photographs of rare consoles and vintage studios.

The Bible of studio tech books is Kevin Ryan and Brian Kehew’s Recording The Beatles, which goes so far as to have diagrams of microphone placements for every track The Beatles recorded. Massey’s is right up there; it’s almost unbelievable that no one has done anything like this before. Parsons’ sits among many similar works and doesn’t benefit from enough personal stories. The other inherent problem with books such as these is the fact that for every rule applied there’s an opposing view that could equally apply. Parsons presents a myriad of possible suggestions, though many, in my opinion, would be a complete waste of time. Time is the ultimate currency when recording.

Massey’s book makes me feel very emotional, I’ve spent thousands of hours in many of these studios and they simply don’t exist anymore. Looking back it feels like a dream, these beautiful sonic temples have now been reduced to sand and sucked into the digital abyss. Significantly, these two volumes coincide with a renewed and widespread obsession with analogue recordings that will hopefully culminate in new recording studios being built.

What Massey’s book communicates is how much we’ve lost, and how fast the world has changed. Hopefully this unquenchable desire for new tech will enable us to 3D print our own vintage Neves and Fairchild compressors, until then I’m still buzzing from all the new software tech advances. Daniel Miller (Mute founder and pioneering 80s analogue synth artist as The Normal) recently showed me an Arturia app for a rare OBX synth. A real one costs £300K. The soft one? £6.99. And it sounds amazing. Technology has always been at the cutting edge of creativity, but the ideal is to find equilibrium between the old and the new.

Ten years ago someone told me the future of music was in education and in many ways that’s been proved right. New music will always find a way to get recorded, whether on wax cylinder or HD. Meanwhile, I’d better get started on my masterclass book.