When asked about Sony releasing outtakes and complete recording sessions by Miles Davis, Teo Macero, producer of the original, scrupulously edited albums, was unequivocal in his opposition to the advent of the multi-disc, warts-and-all box set. “I think it’s a bunch of shit, and you can quote me on that. And I hope you do. It has destroyed Miles and made him sound like an idiot... Those records were gems, and you should leave them as gems.”

The increase in expanded, enhanced and far-end-of-a-fart packages is also seen in some quarters as little more than a cynical cash grab by record companies, conning punters into buying newfangled versions of things they’ve already bought. Yet the further away we get from their initial release dates, the more these albums invite a scrutiny that’s qualitatively different from earlier critical assessments. Where once we were simply enthralled by a record’s mystique and magic, more than 30 years on, we now want to understand how the trick worked.

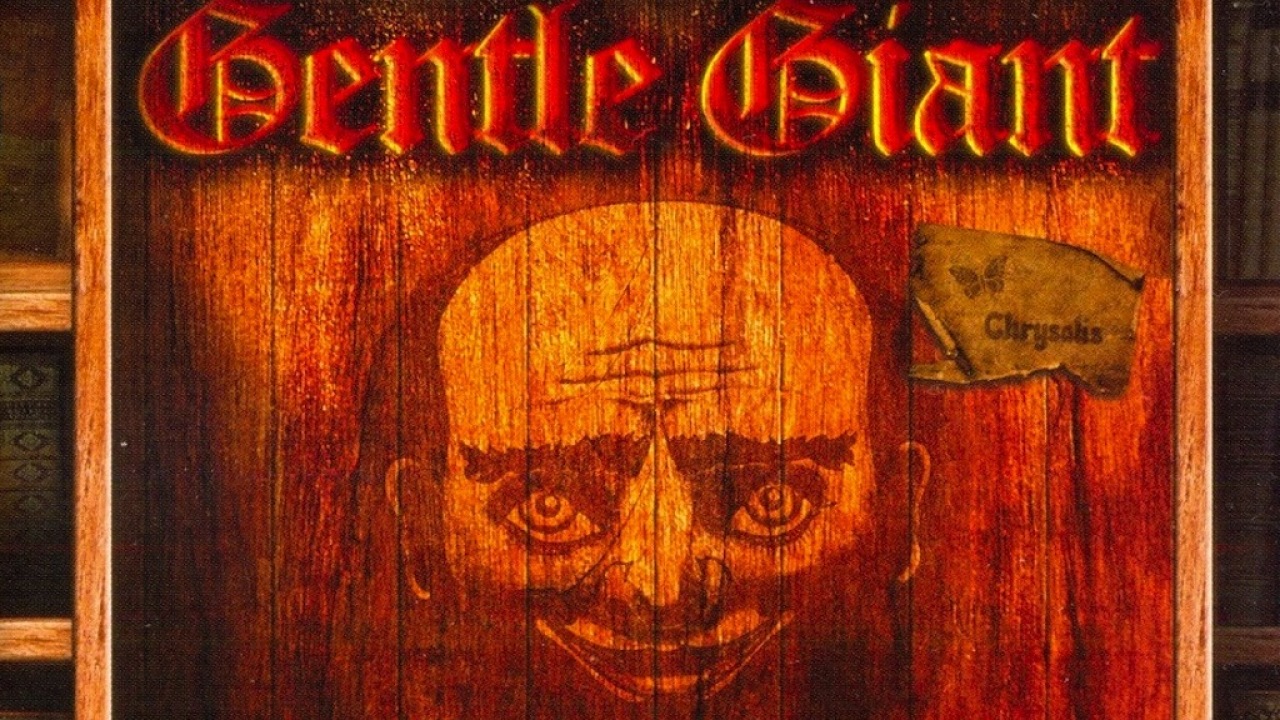

Gentle Giant have previous form with self-referential releases. Under Construction (1997) and 2004’s Scraping The Barrel, from which this five-disc set is largely recycled, highlight in nitty-gritty detail the sheer slog and hard graft – in essence, the scaffolding – that goes into putting their music together. Though frequently ornate and embellished, it’s nevertheless hewn and fashioned from the roughest of materials. The 12 minutes of Kerry Minnear doggedly plugging away at the piano, restlessly scratching at an itch just slightly out of reach, as he nudges ever-closer to the final form of I Lost My Head is probably way too much detail for your casual fan, but it’s meat and drink to the hardcore GG enthusiast.

If we learn something about the mechanics of their writing, then we also gain a revealing glimpse into the state of the band’s strained psyche. 1977’s Sight And Sound concert for the BBC (the first time on CD for this show) fizzes with characteristic panache and not a little swagger. However the older numbers – the slippery grooves of Free Hand, and On Reflection’s incongruous but audacious mediaeval concoction – sparkle with such sophisticated originality that they easily outshine the setlist’s newcomers. “This new stuff is a load of garbage which we’re going to record after the tour,” says Derek Shulman, announcing As Old As You’re Young at a dress rehearsal in front of the press at an otherwise deserted Pinewood Studios in 1977. Tongue-in-cheek bravado perhaps, but it also illustrates the frustration and doubt creeping about the band’s shift in direction which The Missing Piece represents. The rule of thumb here: the straighter the time signatures tend to be, the more prosaic the material.

Kerry Minnear judges 1978’s Giant For A Day to be “one of the less interesting albums now, because it doesn’t really carry the weight of the others”. It’s a blunt but honest assessment. Even the five demos for the album appear jaded and unconvincing. Tired of being perennial square pegs, Gentle Giant quit after 1980’s Civilian. The last disc of this release features their final gig. Hailing from less than pristine sources, this spirited and somewhat raw performance is blistering with last-hurrah fizz. The band pull less impressive numbers up by the bootstraps, ensuring that far from going out with a whimper, they go out with a bang.

Drummer John Weathers’ self-deprecating quip that Gentle Giant were a “boogie band playing Bach” neatly summarises the intensely polymath-like inquisitiveness at the heart of GG’s approach. Even on the grainy bootlegs and scratchy demos assembled here, they produce something that’s extraordinarily robust and rather remarkable.

Though not for newcomers, these archival exhumations, like the manuscripts of novels or the preliminary sketches of painters, provide an alternative account of how Gentle Giant exercised their prodigious creative judgement. Teo Macero is right about original albums being something precious, but blowing the dust from the vaults this way doesn’t diminish the integrity of the artist’s journey. Rather, it tells us something about the means by which they arrived at their destination.