You can trust Louder

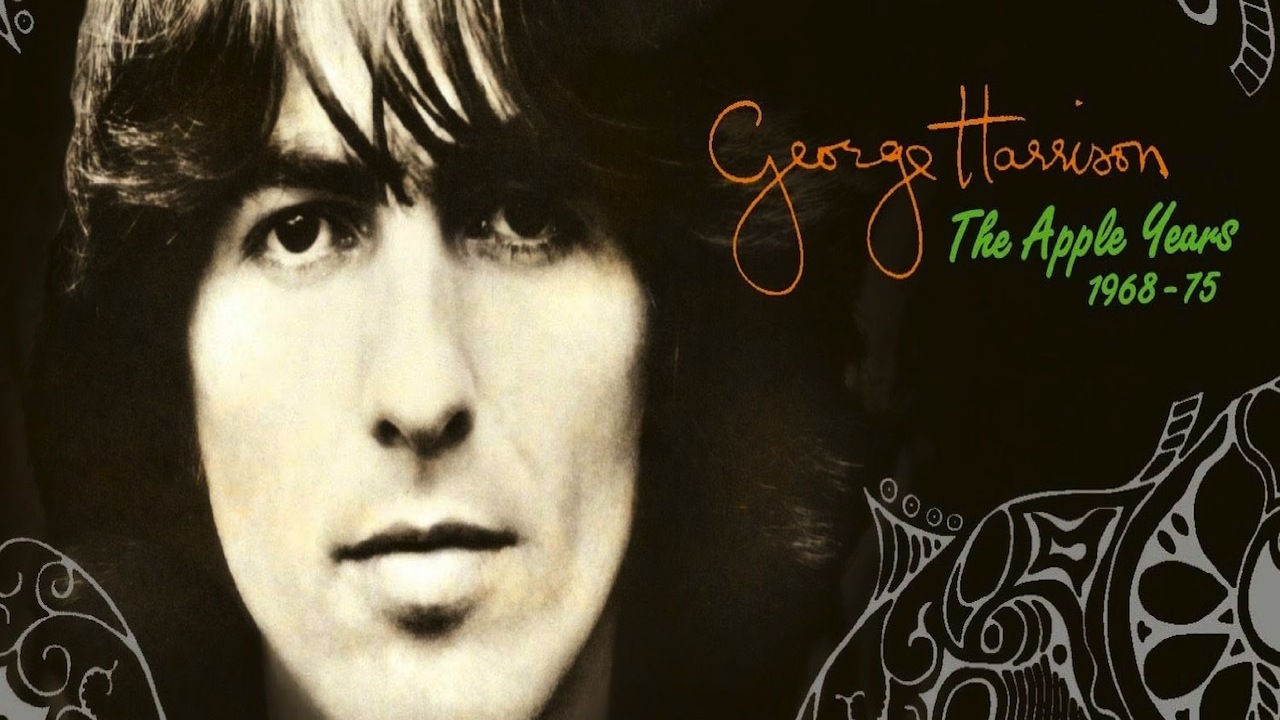

It’s testament to the beautifully indefinable nature of creativity that George Harrison started out a journeyman and ended up a visionary. His first songwriting efforts for The Beatles, even some of his guitar riffs, were laboured, verging on the dour; by the band’s break-up his work was effortless, transcendent.

The fastest Fab off the solo starting block, Harrison was the first to score a No.1. Yet a decade later the plaudits dried up, and his solo work was dismissed as dated and worthy. Now, with all his Apple work gathered together for the first time, it’s clearer than ever that Harrison’s exploration of music’s rural roots, his yearning for transcendence, and his rejection of materialism, mark him out as the most forward-thinking Beatle.

Of course, it’s All Things Must Pass, long portrayed as his masterwork, that forms the centrepiece of this box set. The version here retains the extra tracks of the 2001 reissue, and sounds fresh despite its familiarity. Run Of The Mill is the perfect example, for it’s anything but. Like many of Harrison’s songs, the opening and chords are sweet, reassuringly recognisable, but just as we settle down the melody skips away, aided by his trademark trick of a brief switch of time signature. It’s dazzling craftsmanship – yet sweet and unforced. The well-known songs stand up well, too.

The surprise of this set, though, is the albums whose quietness and introspection were out of tune with the mid-70s. Dark Horse received a critical mauling thanks to the sprawling, bloated tour that promoted it, yet it’s packed with beautiful, small-scale moments. Simply Shady is a shamefaced confessional on the banality of drunkenness. The title track is a fine song, but it’s marred by George’s voice, tired, worn and sapped of its usual sweetness. The bonus, acoustic version puts things right; impassioned, but subtle. Only Ding Dong, Ding Dong embarrasses: George’s own Frog Chorus, its clunking glam evokes those horrible 70s TV shows where DJs drool over dollybirds in hotpants.

Extra Texture, in contrast, boasts neither the highs nor lows of its predecessors. It’s the work of a man wounded by criticism. You, something of a hit and often hailed as the album’s standout, sounds dull today, with its dated sessioneer funk. In contrast, it’s the confessional songs that have worn well. World Of Stone demonstrates that knack for taking a sweet melody in an unpredictable direction, Tired Of Midnight Blue is a beautifully constructed lament to a tedious night out, and Grey Cloudy Lies a dark exploration of the depression into which he’d sunk in 1974, after being mocked for his spiritual homilies. Today, when pop stars swig Cristal and flash their pecs on Instagram, we can appreciate the irony of Harrison being attacked for preaching enlightenment.

Did he, in his worthiness, exhibit hubris? For sure there are failures here. Electronic Sound, an exploration of Moog’s modular synthesiser, was pioneering at the time, but its first side, especially, sounds timid today. Likewise, on CD as on vinyl, it’s unlikely you’ll listen to the jams that conclude All Things Must Pass more than once, while much of Wonderwall Music has only novelty value. Yet for all its flaws, Wonderwall’s renewed availability is welcome: Harrison was a talented film composer with a gift for evocative soundscapes, like the dreamy Greasy Legs, the serene Dream Scene and the rollicking groove of Party Seacombe.

Still, Harrison’s best work on here boasts much bigger ambition. Why can’t a pop star dream of a better place? All these years on, it’s his most overtly spiritual album that sparkles today. Living In The Material World, long overshadowed by its sprawling predecessor, sparkles with many gems. The well-known songs, such as Sue Me, Sue You Blues (dedicated to the rapacious Allen Klein), stand up well, but it’s the more restrained tracks – Don’t Let Me Wait Too Long, Who Can See It – that entrance: gorgeous pop songs, all the more forceful for their restraint.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The towering achievement of this album is, you might say, the preachiest song, Be Here Now. A straightforward evocation of Buddhist philosophy, its modal folk riffs and wavering melody are enchanting. Writer Ian MacDonald suggested that Nick Drake’s River Man was based on this same Buddhist notion of mindfulness, and there’s a similar combination of dreaminess and fierce intensity in this song, which is a masterpiece.

Does it match The Beatles’ Apple output? No. But what does? Viewed as a whole, though, this set cements Harrison’s reputation, not as a huge 60s phenomenon but as a human – one who is sorely missed.