When the Assembly Hall audience roar their approval at the end of Glenn Hughes’s 90-minute set, Hughes gives it right back: “Thank you so much. You have no idea how much you have done for me. Thank you all for your love and support.”

His sincerity reflects the emotional torment he’s currently enduring, touring while his much-loved 90-something mother lies in intensive care. Earlier that afternoon, Classic Rock learned that Hughes had flown in from California a couple of days ahead of the tour so he could visit his mum and, perhaps, see her alive for the last time.

It’s a grim thought and, even on stage, not one he could shake off. Twice he drew strength from post-song euphoria to deliver a dedication: “I love you mum. I hope you get well soon.”

Hughes, clearly, is a trooper. Looking way short of his 64 years, he’s spending January and February playing 10 dates in the UK and 14 more in continental Europe. The second British show is at Islington Assembly Hall, a 1930s civic building adjoining the north London borough’s Town Hall on the fabulously trendy Upper Street. On this Saturday afternoon, the white Rolls-Royce parked outside for a wedding garners rather more attention than the tour bus and trailer.

As the crew load in – and wrestle with the rear-stage rail that initially pitches the ‘Glenn Hughes’ logo at an eye-catching angle – the icy afternoon air spills in and the temperature indoors drops too. After a quick chat with people from his record label, Frontiers, Hughes ushers Classic Rock’s reviewer and photographer into his dressing room. Doors are closed, drafts minimised, but coats remain on as, keen to look his best for you and photographer Kevin Nixon, Hughes teases his dyed mop in the mirror. He sidesteps my gentle ribbing about his former Rapunzel-like tresses by sighing: “It’s just hair. I figured if I’m returning to ‘rock’, if you will, I would grow it a little longer.”

He thanks me for my (gushing) review of his latest album, last year’s Resonate, but wants to set the record straight on my presumption that the use of purple on the album cover was him looking back and paying homage. “The purple had nothing to do with Deep Purple.” he says. “I just love the colour. I swear to you, I was not trying to go and be something I used to be. I have never rewritten a song. I’ve never tried to rewrite anything I’ve done before, I’m always writing new music. And stretching the boundaries. I did my last album eight years ago – First Underground Nuclear Kitchen was a real funk album. This one, I wanted to get completely back in the rock box.”

Resonate is in that box, no mistake, but Hughes’s trademark soulful vocals elevates it to one of the best records of his career. The heavier his music gets, the more spectacular the contrast provided by that voice. How did he retain the soul while amping up the rock?

“I had no choice. When I was fifteen my girlfriend’s brother ran an all-night discotheque in Walsall. I used to fetch his… coffee on these all-nighters, and the music he was playing was Tamla Motown. When you’re fourteen or fifteen, the music you hear is embedded in you. I could have been listening to Bob Dylan, and if I had I probably would have been a folk guy. The music spoke to me. The Beatles spoke to me too. But all those years later, when I did meet my heroes, particularly Stevie Wonder, I’d already had Tamla Motown injected into my system every weekend, weekend after weekend. It became who I am.”

That identity, though, has never been set in a permanent musical frame.

“Right at the end of my time in Trapeze, when I was making the album I didn’t finish, it was very, very funky and soulful. Trapeze were moving very fast from Medusa [1970], which was hard rock, to You Are The Music [’72], which was really funky rock. And the next album might even have been done in Memphis. I was heading more in the Traffic vibe than into the rock-metal thing.”

That, though, was where he went in 1973, when Deep Purple came calling – although that band’s sound was transforming too.

“My love of music has always been inspired by Detroit. It’s what I listened to. Robert Plant will tell you it was the Mississippi Delta for him. Probably Jimmy [Page] too. Their influences are very obvious. Mine were singers like Otis Redding and Marvin Gaye and people of that ilk. I find it very disheartening when people accuse me of coming into Deep Purple and willingly trying to change the sound of the band. They were checking me out for one year – one full year – before they asked me to join. They knew what they were going to get – and I think it was a good thing.”

It was. Touring the Burn album in 1974, Deep Purple became the biggest-grossing act in the world. And when their show headlining California Jam (attended by at least 250,000) was later broadcast on US TV, David Bowie watched and reached out. He was in town doing seven Diamond Dogs shows at LA’s Universal Ampitheatre, and Glenn Hughes was staying in the same hotel while Purple recorded Stormbringer. An unlikely friendship began, Bowie living with Hughes at a house in Beverly Hills for two years during which all kinds of debauchery ensued and, eventually, Bowie’s Station To Station emerged.

“He was fascinated with how a guy could join a band like Deep Purple and sound like I did, because he was about to make Young Americans and go into his blue-eyed soul thing. He didn’t really see the hair and the clothes, he just heard the way I was singing, as I had on You Are The Music. I was fascinated, too, by that. He made me feel really special. I was a bit blown away. I was the only guy in Purple he really gravitated to.

“Eventually he started complaining to me about my hair – and my boots. If you look back at pictures of Deep Purple, you’ll see there was a point when I’m short. It’s because everyone else was still wearing the platform boots, and he’d thrown mine out!”

Bowie also encouraged Hughes to make the radical style changes that have defined both their careers – sometimes to the frustration of fans of Hughes’s rockier style. Sometimes, though, it’s the unexpected that works the best, as with the bonus track on the special edition of Resonate: a cover of Gary Moore’s Nothing’s The Same, on which Hughes sings accompanied by only Luis Maldonado’s acoustic guitar and cello by Anna Maldonado. Some call him the Voice Of Rock, here he’s closer to George Michael. It’s quite amazing. How hard does he have to work to keep his voice in that sort of shape, especially while on tour?

“If you saw me at the Jon Lord tribute thing at the Royal Albert Hall doing This Time Around… If you put me on stage in front of an 83-piece orchestra, if you give me that, it’s going to be fucking on! I didn’t use a microphone for the opening part of the song, I just sang into the gods of the Albert Hall on my own. I swear to you, I’m not the sort of guy to sit in front of an interviewer and be fake. Jon Lord was right on my shoulder. [He pats his shoulder for emphasis.] I felt him, and I sang it like the first time I ever sang it. I got on my knees at the end of that song and I was torn to bits.

“And when I sang that Gary Moore song, it was the first take with the acoustic guitar. It’s the breathing and the timing… [He suddenly sings: ‘Another time, another place…’ to underline his point that he can just switch it on] …the emotional quality that I like to sing with. That track is my complete tribute to him. We had a falling out years ago when Gary said some stuff in the papers, which was really embarrassing [Moore shamed Hughes, who was still taking drugs in those days], but we made friends before he died, and when I got the chance I recorded this for Gary. I have nothing but love for him.

“You can just give me an acoustic guitar. I don’t have to have all this noise and racket going on, because I have a voice. I’ve heard what people say: ‘He’s a screamer.’ He’s this. He’s that. ‘He oversings.’ And yes, I can do it all. But I’d rather have one note – one long, breathing note. I’m still learning how to sing.”

Did you ever have lessons?

“No. Well, at choir. I say this: I will be studying vocals until I’m dead. I will be studying playing the bass and playing the guitar until I’m dead. I am not the finished article. I never want to stop learning.”

But touring like this – why do you still do it?

“I have to do it. I know I’m sober because I’ve been given this voice, if you will. And with this voice has come the ability to write songs – a lot of songs, lately. And with that I’ve suffered. I had heart surgery three years ago, double knee surgery. I had a car crash fourteen months ago in which I almost died. I’ve had so many different things happen to me, strange and horrible things happen to me, that have made me realise… When George Michael died… Actually not just George. How many people have we lost lately? I live one day at a time because you never know what will happen tomorrow.

“I’m going through so much sadness over my mum that I have questioned and thought: ‘When is it going to end?’ [His father died last April, on the very day that Hughes was inducted, with Deep Purple, into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame.] I’m not thinking I’m going to die. I’m in great health. But I know I’ve got to give it my all. And I think I’ve been doing that for some time now. So it’s so important to me to live a sober lifestyle – which we know about. And I’m carrying this love sack with me, this huge love thing. I’m a real love fanatic, you know. I don’t know what the word ‘hate’ means. I haven’t got a clue.”

He says he likes to give the love on social media too, and insists: “It’s me talking to them on the internet. I do have a team of people working for me, but usually it’s me talking to them.”

Ironically, at the time you met Bowie neither of you would have gone anywhere near the fans.

“There are some fans out there – haters, if you will – and I completely forgive them because they have their problems. That doesn’t really affect me, it’s just the way they are. For others, I can see that what I do means something to them. I openly talk to a lot of people.”

He’ll get a chance soon, right after soundcheck. That process is begun by the crew, before Hughes and his band – guitarist Soren Andersen, drummer Pontus Engborg and Hammond organ star Jesper Bo Hansen (better known as Jay Boe) – blow away any remaining Assembly Hall cobwebs with the mighty Flow, from Resonate. As they do so, the two dozen or so VIP punters await their call, peering through the doors at the back of the hall. These fans have each paid 99 dollars (around £80), on top of the modest £25 ticket price, to be here early. The song thunders to its conclusion with one of the crew kneeling in front of Engborg’s huge bass drum with his hands over his ears, listening for God-knows what.

After it ends, Jay Boe – addressing Hughes as ‘Papa’ – checks that the organ wasn’t too loud in Hughes’s monitors, politely avoiding the fact that his own left ear is about three feet from Hughes’s wall of Orange speakers. Everyone’s happy, and so the doors open.

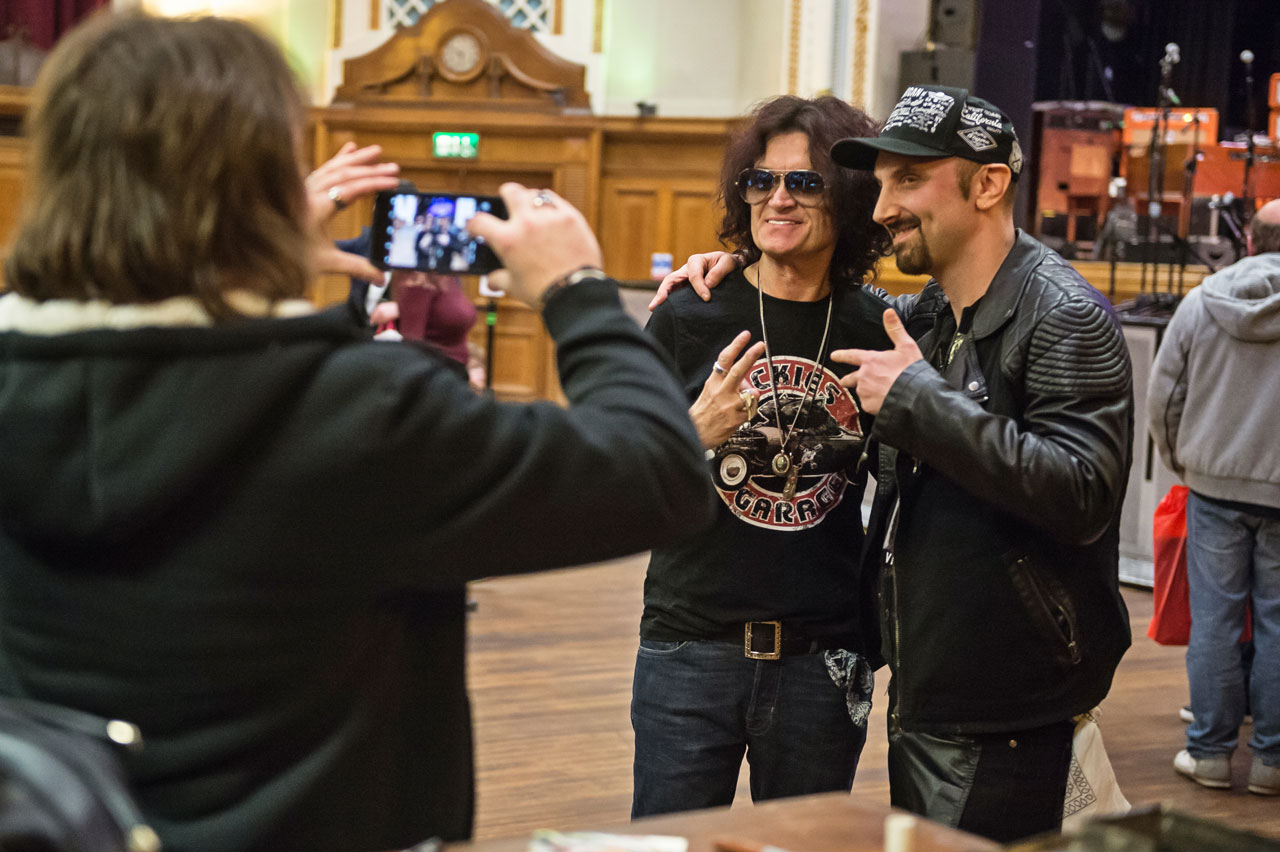

The meet-and-greeters assemble in front of the stage. Hughes welcomes and thanks them, then leads the band in a note-perfect Muscle And Blood, the Hughes-Thrall number from 1982. As the final echoes fade, Hughes puts down his retro-style Nash JB-63 and moves from stage to floor to meet the fans.

While waiting their turn, Londoners Ian and Guy tell me that attending classic rock gigs is their joint hobby, and enthuse about a forthcoming Rainbow show. Others are more partisan, perhaps none more than Cassio, originally from Brazil, who has flown all the way from Portugal. He’s spent around 400 Euros to listen to and meet Hughes, “because he does not play Portugal this time, because his voice is everything. Not like David Coverdale, who has lost his…”

Meanwhile, Hughes chats, poses for photos and takes the trouble to check the spellings of names before signing autographs. As he said earlier: “I don’t look at myself as the Glenn Hughes that they see. I’m just the Glenn Hughes who’s sitting here talking to you. A guy that’s been given a gift. My job is to freely give that gift back.”

A little over an hour later, the house lights go down and Stone Broken take to the stage. The venue holds around 800 and it’s not quite full, but it’s close enough and the vibe is good. Stone Broken are labelmates and from the same part of the world as Hughes; guitarist Chris Davis is from Hughes’s home town of Cannock, and the band call nearby Walsall home.

Playing mostly songs from their debut album, they do well, and new song Just A Memory hints at future success. Before their final song, frontman Rich Moss thanks the audience for their warm reception: “It was good last night in Newcastle too, which I guess proves Glenn Hughes fans are the best in the world.”

The hall gets a little fuller, and then the headliners kick off with Flow, Hughes stomping the stage, resplendent in a red-and-black waistcoat and tails outfit that matches his guitar. At the back, Engborg thunders along, a hugely powerful drummer with a Bonham-like approach. Muscle And Blood comes next, followed Purple Mark IV’s Gettin’ Tighter, from 1976, and for Andersen, on a cream Stratocaster, a chance to show off his Tommy Bolin chops.

After that it’s back to Hughes’s current solo album with Stumble & Go, which matches its more famous predecessor on merit and impact. Hughes delivers every line, every word, with the clarity and power he’d spoken of in the dressing room earlier. His bass is powerful too, with Hughes at times playing rhythm guitar parts on it.

“I love you, mum!” he yells, then introduces Medusa as “a song I wrote in my mum’s kitchen when I was seventeen. True.”

The Trapeze classic sounds mighty and is truly inspiring. After it, Hughes pauses to reach for a blue handkerchief and pokes fun at himself: “The old man has a runny nose. I’ve just been to South America. And thirty years ago there would have been another reason, but it’s been twenty-seven years since I had that demonic devil’s dandruff…”

And so to Can’t Stop The Flood. The band look like they love playing it, and Jay Boe’s Hammond organ adds more than a shade of Jon Lord. From there they head straight into Black Country Communion’s thrilling One Last Soul, then back to Purple Mk IV for You Keep On Moving.

As that gives way to Resonate’s gargantu-rocker My Town, BCC’s signature Black Country and finally Hughes’s own funk-rocker Soul Mover, the set-list has been so good that there’s really only one song that everyone is still expecting to hear. When the band return for the encore, they postpone it for a few minutes by playing Resonate opener and mission statement Heavy. Which, of course, can only be followed by a note-perfect Burn. At its finale, bows, waves and love flow from stage to hall and vice versa.

Minutes later, a beaming Soren Andersen strides back into the catering area, now playing air guitar. He admits that while it’s a huge thrill to play Burn as the final encore, it’s pressure, too. “I’m following in some pretty big shoes there,” he explains.

He needn’t worry, the shoes fit perfectly. And Andersen is perfect for Hughes, swapping guitars during the set to maintain a vintage feel on songs that might be separated by seconds on stage but decades in their original recording. As co-producer of Resonate, he also deserves huge credit – and indeed received some earlier in the week from no other than Joe Satriani in an online ‘5 Amazing Guitar Albums You Never Heard’ piece. Keyboard player Jay Boen strolls in, and the pair agree it was a very good show, better even than the opening night in Newcastle.

As a showered and changed Hughes signs a pile of fans’ album sleeves, he still insists he’s “just a regular guy from the West Midlands that was so grateful to have been given the gift of music. There’s nobody this year that you’ll speak to that’s more grateful than I. Nobody.”

Glenn Hughes: The 10 records that changed my life

Glenn Hughes' track-by-track guide to Resonate

"Don’t fry bacon when you’re pissed..." The Gospel According To Glenn Hughes