With rock now settled into middle-age, the temptation for well-heeled artists to drift into their dotage performing ‘greatest hits’ tours or classic albums in their entirety becomes ever stronger. However, as anyone who has heard Bat Out Of Hell II (or, shudder, 3) could tell you, rebooting former glories for the 21st century is a far trickier proposition.

On the one hand, it piques the interest of old fans for whom new material is as appealing as root canal work. On the other, it suggests a drying up of the creative well, and, worse still, can threaten a reputation which has taken decades to build. All of which brings us to Thick As A Brick 2.

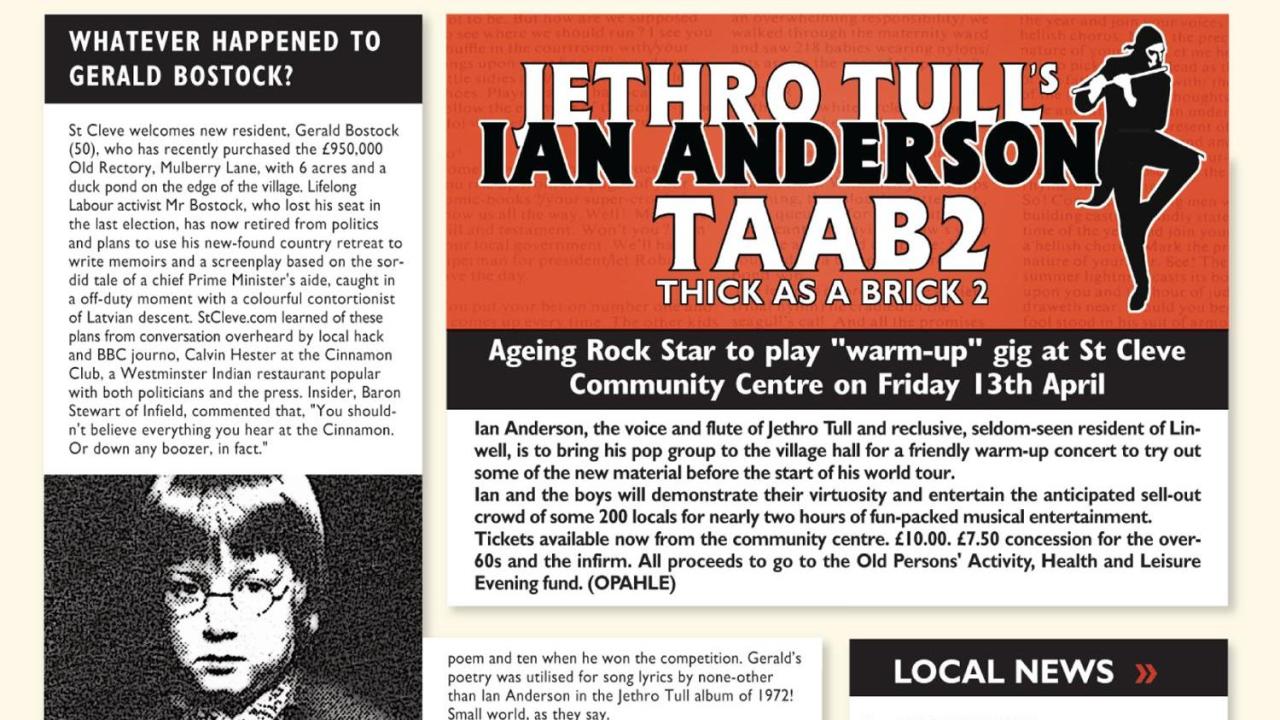

Written in a two-week spurt of creativity in February last year, it is the wholly unexpected follow up to Jethro Tull’s classic fifth album; 43 minutes of bombastic brilliance, with lyrics supposedly written by precocious 12-year-old schoolboy Gerald Bostock. From the knowing sleeve – the St Cleve Chronicle of the original has now become a website – it’s clear that Tull mainman Ian Anderson is approaching such a monumental task with his sense of humour intact.

Accordingly, while the original was designed to mock the pretensions of prog rock’s ruling elite, this time around he uses Gerald’s fate as an excuse to muse on fate and free will. ‘Which way to blue skies?’ asks opener From A Pebble Thrown. After which Bostock’s possible future as captain of commerce (Upper Sixth Loan Shark), military man (Old School Song) evangelical preacher (Give ‘Til It Hurts) and suburbanite (Kismet In Suburbia) are explored over a 53-minute song suite with enough shifting musical styles and time signatures to please fans of the original album.

Lyrically, however, Anderson is bang up to date, cursing current conflicts and corrupt financiers amid scattered references to everything from eBay to ‘Starbucks muffins’. Some grumbles: Tull aficionados will mourn Anderson’s decision to exclude guitarist Martin Barre from the project; and the music never matches the high-wire intensity of the original. But unlike, say, Pete Townshend’s attempt to provide an adult resolution for Quadrophenia’s Jimmy in White City, Anderson’s tale never feels forced or phoned-in.

On the contrary, TAAB2 is proof that living in the past is possible, and also opens up a Pandora’s box of possible prog sequels. The Wall 2, anyone?