Outside of Frankie’s pleasuredome and Dexys’ dungaree incinerator, no one in the 80s ever admitted to sweating. This was the decade of the pristine, the age of immaculate aristocrat make-up, sculpted fringes, and trousers cut to allow for the maximum air circulation. Pop music was clinically synthetic, sleek and vacuum-moulded; no star worth their Stock Aitken Waterman remix would ever do anything as human as perspire.

So when, in 1987, INXS frontman Michael Hutchence rolled up in a zip-strewn biker jacket behind a swarthy guitar riff and pouted ‘there’s something about you girl that makes me sweat’, we barely knew what to make of him. He and his band of Australian gloss-rockers had all the plastic funk grooves, silvery synth touches, sax solos and soul harmonies of popular contemporaries such as Fine Young Cannibals, the Human League, Duran Duran, Level 42 and Curiosity Killed The Cat, but they were fronted by a lizard-hipped sex mop with clear aspirations to be the Jim Morrison of his day. With one purring ‘slide over here and give me a moment, your moves are so raw’, INXS became the safe, sanitised sound of 80s sexuality, the Kylie fan’s (and, later, Kylie’s own) bit of rough. A band more likely to make you feel like a million dollars in the sack than Howard Jones, but less likely to leave you encrusted with soiled dairy products than Prince.

Very much an Australian phenomenon until ’87 – their many Australasian hits had barely registered in the UK – their sixth album, Kick, landed like a Thor’s hammer of lascivious arena pop, a virtually faultless, laser-targeted collection of synthetic sleaze that spoke of a band arriving fully formed at the very peak of their songcraft. After 10 years spent quietly polishing up their Boomtown Rats-style new-wave pub rock and trimming their mullets for the spangly new decade, they were the Down Under U2, slamming from the ether with their very own Joshua Tree or, in Peter Gabriel terms, delivering their So without the wider world knowing they’d ever worn a sunflower helmet. Seductive nightcrawler Need You Tonight was like a glowing neon calling card reading ‘NEW IN TOWN’ tucked suggestively into the breast pocket of the top five, and once we made the call they sure kept showing us a good time. Devil Inside was 80s pop licking a forked tongue. The shiny funk blast of New Sensation sounded like a duel between rival gospel gangs on E Street, orchestral last dance Never Tear softwareuiphraseguid=“238a8241-a9a2-4a72-b005-dc1bab9f79b5”>softwareuiphraseguid=“238a8241-a9a2-4a72-b005-dc1bab9f79b5”>SOFTWAREmark” gingersoftwareuiphraseguid=“238a8241-a9a2-4a72-b005-dc1bab9f79b5” id=“a04db39f-7ddd-4aed-9259-97c298118153”>UsApart, easily the coolest doo-wop ballad of the decade (sorry, Flying Pickets), proved there was heart beneath Hutchence’s biker threads.

The album itself didn’t stop kicking. From the opening snap, crackle and sex noises of Guns In The Sky it teetered on the mainstream’s edge, flirting with the language and imagery of danger and rebellion but with its studded gloves clasped firm on the throat of the 80s commercial aesthetic. Hutchence twisted his enigma throughout, by turn radical hippie free thinker (ethereal quasi-rap Mediate), rebel without a cause (Wild Life) and elemental playboy (the sultry Mystify). By the record’s end he’d proved himself the blueprint for the ultra-modern rock’n’roll lizard king; you can easily imagine Bono studying a song like Devil Inside, with its sordid fascination with knives, leather and the wickedness within, and summoning forth The Fly and MacPhisto in Hutchence’s image.

For all the supersonic Motown horns of the title track, the John Hughes prom party vibe of Calling All Nations and the climactic sparkle of Tiny Daggers, it’s The Loved One that best captures the essence of Kick: a studio-sterilisedgrindhouse groove oozing slick sensuality, which slides effortlessly into a chorus born to rattle Red Rocks.

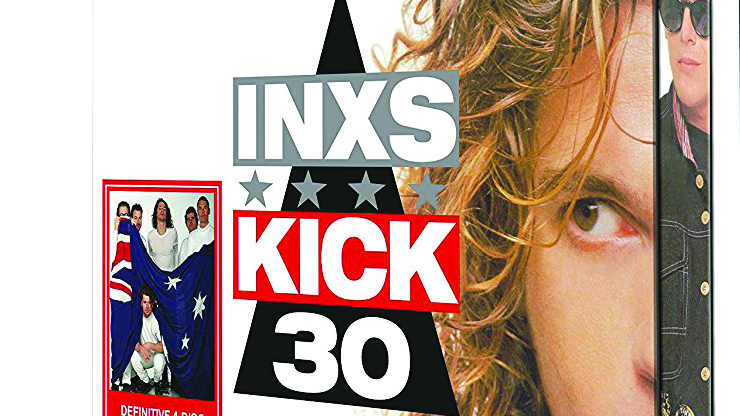

For such a strong, consistent album, it’s bewildering that there’s so little worthwhile second-tier material to be excavated for this anniversary edition. The package cobbles together reams of rolled-up-blazer-sleeve remixes, live tracks and surprisingly pointless B-sides:; Isoftwareuiphraseguid=“15553d49-543a-4225-ac56-04c59cd18a70”>’m Coming (Home) sounds like they bugged a brothel, then whacked five minutes of extraneous funk and Barry White impressions over the top; On The Rocks is throwaway scat jazz; and the acoustic demo of Jesus Was A Man has Hutchence drooling cod-philosophical nonsense about Jesus, Ghandi and Hitler like John Lennon falling over pissed. Do softwareuiphraseguid=“2a8347f0-c763-4e76-b9d5-29f06a351094”>Wot You Do and Move On are worthwhile additions, but the lack of studio overflow only makes the album’s 12-track bullseye seem all the more superhuman, and its rejection by three record labels all the more unfathomable.

Move On’s confession that ‘there’s a monkey on my back, SOFTWAREmark” gingersoftwareuiphraseguid=“a16e914b-dea2-4e31-8622-603faa4151ea” id=“e905ab1f-d8a6-4ed7-a1af-d1140a032dc4”>been there much too long/Every time I kick it off another one comes along’ was a buried hint that Hutchence wasn’t quite the Kershaw in Sixx clothing he first appeared to be. Kick would prove to be the peak of a tragic downward spiral that would see him cremated 10 years later, belt marks around his neck and a gram of heroin slipped into his funeral suit pocket. We’d rather remember him this way: the devil in his hip, a gleam on his lip and the world at his fingertip.