When is a Jethro Tull show not a Jethro Tull show? When it’s an audiovisual rock opera, written and performed by Ian Anderson, who uses filmed backdrops along with Tull’s songs, slightly tweaked in places, to tell the story of the 18th-century farmer, revolutionary agriculturalist and inventor of the mechanical seed drill from whom his band took their name.

Only it’s been updated to the 21st century, featuring the eponymous hero as a futuristic biochemist cloning plants to feed the world. Members of Anderson’s backing band play historical and contemporary roles loosely based on Mr. Tull and related characters. Tull’s music old and new (there are five short pieces especially written for the occasion) provide the narrative as the real-life musicians onstage and individuals on the screen sing in sync with each other.

Confused? You won’t be, because the joy isn’t in working out who’s who, nor in discerning what eco-conscious analogy we’re meant to draw about evolution versus tradition, or attendant conclusions about the value of progress in an era of global warming and diminishing resources. No, the pleasure is in the sheer multimedia overload; the seamless dovetailing of the action real and digital; the performances of the players, particularly mean axeman Florian Opahle; and Tull’s music, which mirrors the message in its blend of the traditional and the modern, pastoral folk merging with proggy Sturm und Drang.

It’s a greatest hits set and a technical triumph.

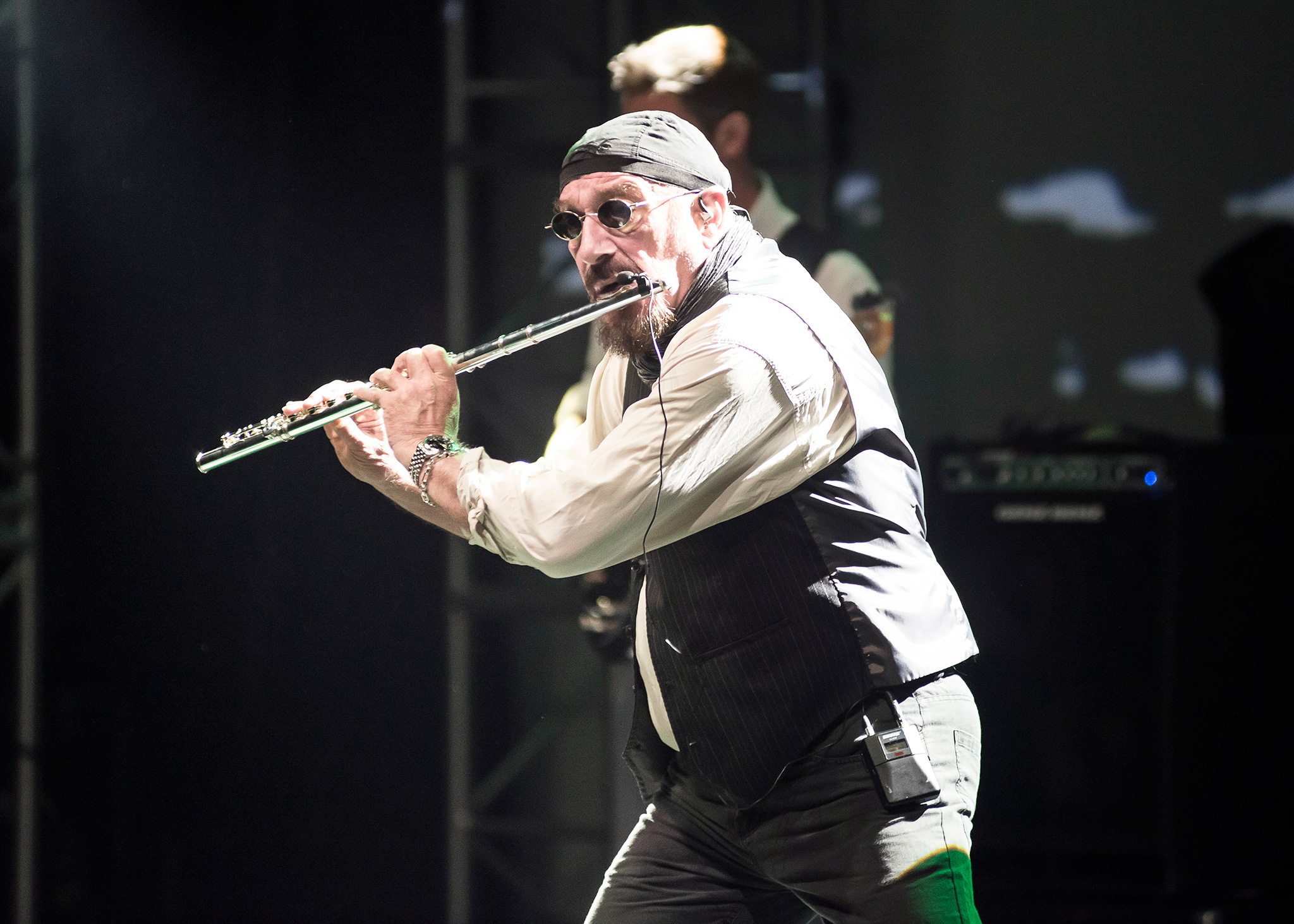

At the centre of it all, of course, is Anderson, in trademark bandana and waistcoat, the oldest sprite in town. Prancing about, flute in hand, he moves with the gusto of yore, even if the hair and Catweazle beard have been replaced by a bald pate and goatee. And when you’re not gawping at this hyperactive sexagenarian onstage, you’re watching him onscreen as The Narrator, resembling a medieval scholar in his cloak and mortar board. Also rather fetching is Unnur Birna Björnsdóttir as Tull’s wife, her clear, pure tones rising above Opahle’s guitar, John O’Hara’s tempo-twitching keyboards, Greig Robinson’s darting bass and Scott Hammond’s punchy drums.

The young musicians are testament to this music’s continued relevance among that demographic. Meanwhile, Anderson – partly thanks, it must be said, to the poetic proclamations of Prog – is a hipper proposition than he’s been for decades. Rather than cutting a preposterous figure, here he seems vital, plugged into what’s current, even as the band reach back into the vaults. Today’s rising prog stars owe this music big time.

“It’s like a ‘best of Jethro Tull’, but in a new context,” said Anderson of this tour, and it’s true: it’s a greatest hits set, with superb renditions of Aqualung, Living In The Past, Heavy Horses et al. But it’s also a conceptual feat and a technical triumph that shows Anderson interfacing brilliantly with the latest technology, ready and willing to bring Tull up to date, exploiting the multisensory potential of their music.