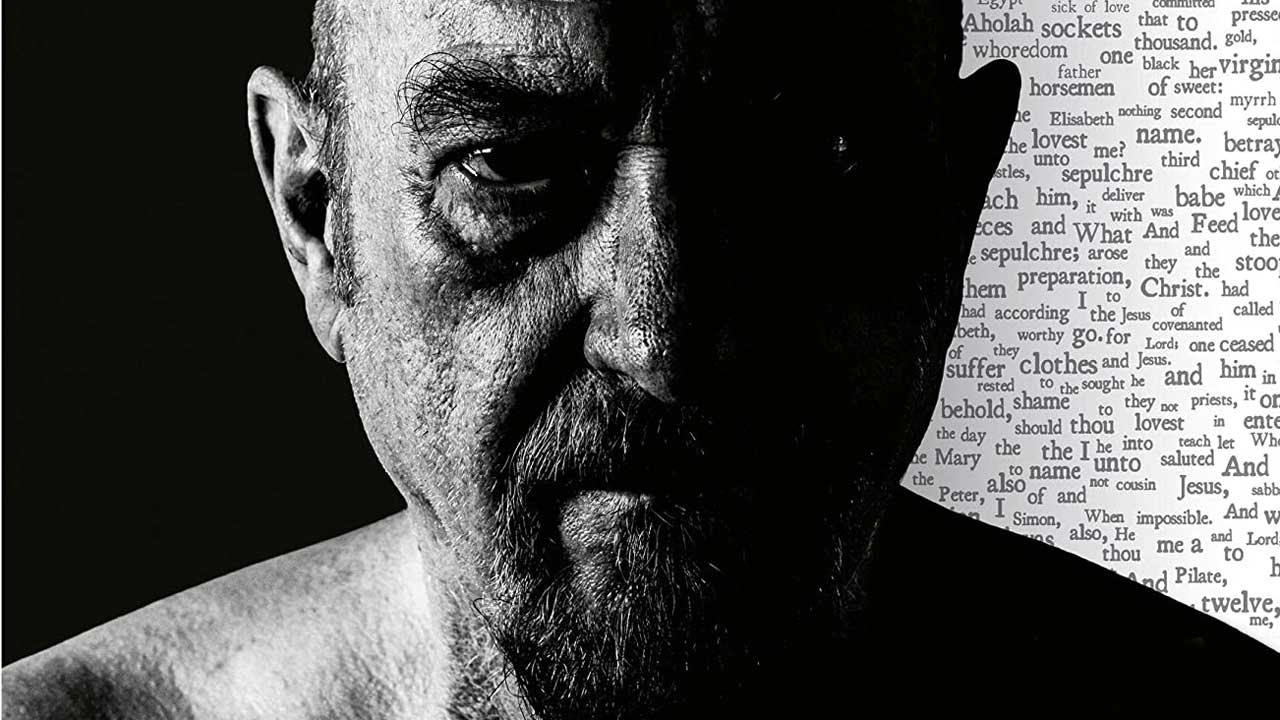

“This is going to put some people’s noses out of joint,” Ian Anderson told this writer recently when discussing Jethro Tull’s 22nd studio record, their first since 2003’s Christmas Album. “But I think of drawing upon elements of the Bible in the same way as I draw on elements of society as subject material for songs. It’s taking something and turning it into something else. It’s what I do.”

Few artists in the progressive realm or beyond make that conversion in such intelligent, idiosyncratic style. Anderson has turned his mind to religion before – Ronnie Pilgrim’s subverted metaphysical journey in A Passion Play; most of Aqualung’s second side – but rarely as directly as this. The Zealot Gene’s 12 songs come subtitled with the New and Old Testament passages that inspired them. The alchemy lies in how these biblical stories are set to music, and made new.

The titular Mrs Tibbets is Enola Gay Tibbets, the mother of Paul, pilot of the plane that dropped the Hiroshima bomb. The liner notes refer us to Genesis 19:24-28 (the bit about The Lord raining down burning sulphur on Sodom and Gomorrah, overthrowing cities and destroying all living things), while the song ponders how an individual can rationalise their involvement with such mass destruction (‘Don’t feel bad about the melting heat, the burning flesh, the soft white cell demise’). A heavy subject is set to a jaunty tune, with Anderson’s mischievous flute and cheeky vocal delivery in the top line. Throughout the record, that trademark flute radiates sheer character. Raspy and fluttering in parts, melodic and mellifluous in others, it’s the musical sugar on the thematic pill.

The line-up that recorded The Zealot Gene (bassist David Goodier, keyboardist John O’Hara, drummer Scott Hammond and guitarist Florian Opahle) are a tight regiment, here to back the boss and showcase the songs. That priority is also reflected by the album’s frills-free production, almost Lutheran in its minimalism.

Referencing Exodus and billed as “a late-life partner to Aqualung’s My God”, Mine Is The Mountain opens with grand, minor-key piano chords and develops into an exquisitely performed piece of prog theatre. With echoing, stentorian voice and ostensibly perched upon Mount Sinai, Anderson makes a good jealous God, exhorting Moses and Man to obey Him, not to mug Him off in any way, or else. ‘Bring me safe haven for tablets of stone to live through the ages, to scold and to guide you, threaten, cajole you and cut to the bone.’ It’s both funny, and also terrifying.

The Betrayal Of Joshua Kynde is a rocky meditation on the Judases of this world (‘There’s always someone to spoil the party fun’), with a bluesy flute riff and a strong solo from Opahle. Evoking Calvary itself, Where Did Saturday Go? has a folky, modal flavour and a beautifully spare acoustic guitar riff. With its gutsy harmonica intro and mandolin lines, Jacob’s Tales is a short, spiky piece about sibling rivalry and greed, à la Jacob and Esau.

The perky single Shoshana Sleeping underplayed the album’s darker tone, but in context this racy piece about voyeurism and fantasy makes thematic sense. Anderson’s aversion to schmaltz endures, but there’s a softness to Three Loves, Three: ‘Be it love of spirit, of brothers, lovers, sons or blood-heat emotion, burning lava, bright it runs.’ The strident title track warns of mankind’s divisive nature at DNA level, the reductive, binary nature of discourse in the social media age and the dangerous allure of “the populist with dark appeal”. It’s strong and infectious, from its martial-metal intro to the coda’s sinister chords, a potent sting in the tail.

Conceived after seeing drunken revellers during a walk through Cardiff city centre one Saturday night, Sad City Sisters references a passage in Ezekiel about two prostitutes, and features ‘Tramps on a night out, out of season/Bare legs and arms at the taxi stand’). Thought-provoking elsewhere, the all-seeing eye and unflinching worldview seem judgemental here – mean, even (‘So send them home to stumble in, and toss their knickers in the bin’.) The gorgeous folky instrumentation – accordion, mandolin and penny whistle – makes it easy enough to turn the other cheek.

Given its biblical source, The Zealot Gene way well put a nose or two out of joint, but

its poetic, erudite and relatively respectful approach should help avoid any spectacular blowback. Anderson’s expectations for it are modest: “Most fans don’t want a new Jethro Tull album,” he told this writer recently, “they want an old Jethro Tull album!” But he who has ears, let him hear: this literate and highly listenable work is a real grower. Ripe with fresh inspiration and resonant of past glories, it belongs high in the Tull canon.