As unseen turning points go, the tail end of 1970 was the coalescence of a perfect storm for Led Zeppelin. Although Led Zeppelin III had just topped the UK and US charts and sold more than a million copies (this running concurrently with Led Zeppelin II still selling at a rate of knots worldwide), its relatively quick slip back down the charts was privately causing ripples of unease in Zeppelin’s inner circle (and, more tellingly, at Atlantic’s head offices).

Damned-if-we-do and damned-if-we-don’t reactions to well-documented critical peevishness had steeled more than a few resolves, provoking new levels of intransigence and tenacity that would prove key ingredients in the creation of the band’s fourth album. As with any iconic piece of art, it’s now virtually impossible to separate the medium from the message, the cultural and visual context from which it emerged, and in which it forever sits.

Musically, a deluge of on-the-spot creativity, arcing off into previously uncharted tangents, was rapidly subsuming the band’s earlier, more obviously blues-based output. Plant’s lyrics were increasingly being redrawn in more fantastical and ambiguous terms, steeped in something more mysterious and arcane: occult influences rubbing alongside Celtic medievalism; Wales as a corner of Albion, Tolkien the narrator; a cocktail of hermetic magic, runeology and conversation-halting riffs that would create the trope for future rock and metal that endures to this day.

To listen to the companion discs (IV 9⁄10, HOTH 8⁄10) accompanying these all-format and much-flagged reissues is at times like being parachuted into Jimmy Page’s producer’s head. One can’t help to-ing and fro-ing from the released version to the earlier rougher mix, teasing out nuances in tempo, tone and parts. It’s an intensive and almost scientific way of listening to music, sometimes exhausting, and the opposite of just letting the emotion and power wash over. However, if as a process it brings you closer to the craft, talent and magic, its purpose is well served.

A word of caution on the alternative mixes: we’re dealing in degrees of subtlety here. Those hoping for a different guitar solo take on Stairway, or Four Sticks with only two sticks will be disappointed; there’s no new brass section in Misty Mountain Hop, no dubstep middle eight in When The Levee Breaks. Such was the level of musicianship and speed of delivery (“You could get three or four tracks done in a night,” said engineer Andy Johns), off-cuts are thin on the ground.

What the companion discs do provide, with illuminating effect, is a new angle, a slight shift of perspective that reveals nothing less than master craft in action. The high guitar overdubs at the start of Rock And Roll are omitted, leaving a stripped-down 12-bar blues crackling with an instinctive scrappy guitar. The harmony guitar lick on the main Black Dog riff is markedly to the fore.

Both Going To California and The Battle Of Evermore are presented without vocals, leaving the listener an unimpeded window on the chiming filigree interaction between acoustic guitar and mandolin, the Hollywood hiraeth of the former still apparent even without Plant’s love letter to Joni Mitchell adorning it. The break in Four Sticks is reinforced by a wonderfully modulated synth part, adding an Indian raga tinge that can be plotted through to the Unledded version of the mid-90s.

The epithet ‘tight but loose’ has always accurately described the band’s aesthetic, and these sparser, more spacious mixes shine more light on this. Squeaks, scrapes and microphone bleed were not errors to be corrected in Page’s production ethos, but rather characterful and inherent ingredients of the feel. That, and the world’s biggest fuck-off drum sound ever committed to tape. Much has been written on the technicalities of this recording – basically two microphones hung above Bonham’s kit set up in a three-storey-high hall – and if anything these new mixes add even more ambience to that ever-sampled sound.

It’s not too much of a stretch to venture that Headley Grange, where IV (10⁄10) was recorded, is the fifth member here. This ambience positively saturates the none-more-familiar finger-picked figure that introduces Stairway, the band’s finest recorded moment (this version being the mythical Sunset Sound Studio mix), near enough adding delay, such is the size of the reverb. The track breathes more, seems more relaxed. Plant’s vocals are chocolate-smooth, almost effortless, Jones’s bass recorders and electric piano are possibly a little higher in the mix, and there’s a centred starkness at odds with the immediacy of the original. Is it ‘better’? Wrong question. Think of it as a prototype, a blueprint, a draft – just one with the world’s greatest ever guitar solo.

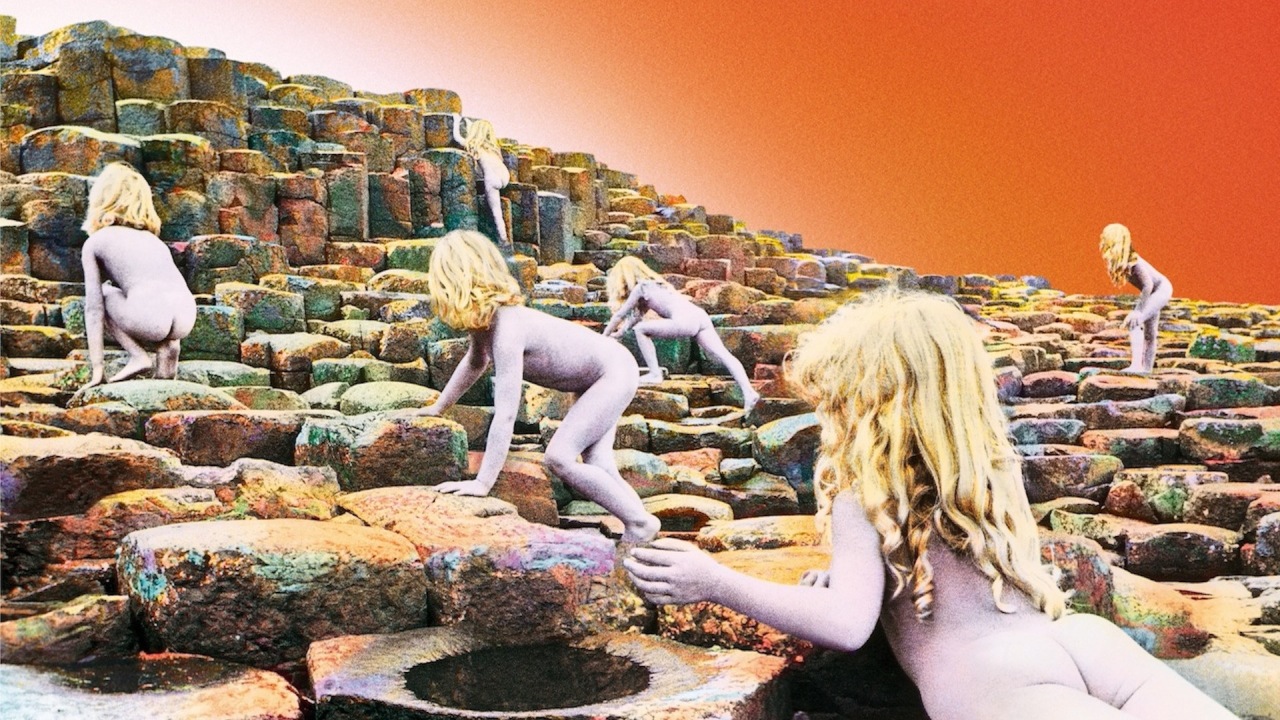

1973’s Houses Of The Holy (9⁄10) (Page: “Children are houses of the holy”) reveals the band in a more playful mode. The empire had been built, 70s rock excess was at its apex, critical pressure had waned and a generally lighter and more colourful mood prevailed. It remains one of their most diverse, underrated, critically misunderstood and fan-polarising albums. Like Led Zeppelin III, it’s a relative disappointment after the monolith that preceded it, and a catalyst for the even greater heights that would ensue (Physical Graffiti).

There’s an attractive and cocksure ‘we’ll please ourselves, thank you very much’ quality on display, and a previously unrevealed sense of humour running very much against the prevalent heavier-than-thou mood of the droopy-lidded fan and critic. Sure, humour is all too subjective, and Bonham and Jones are both on record as hating the shuffle-reggae of D’yer Maker (My wife’s gone to the West Indies…), but there’s little faulting the confidence.

The album’s working mixes here largely serve as a testament to John Paul Jones’s marvellous improvisational skills, nowhere more so than on a glorious _No Quarter _: as with the final version, slowed down a semi-tone, its air of brooding menace standing in stark contrast to the near pop-rock of Over The Hills And Far Away and Dancing Days. Heard here with tremulous keyboard overdubs and without vocals or guitar solo, the restraint and intuition on the piano mid-section in particular is a thing of wonder. And yes, for those who thought they’d never hear such a thing, it does appear that Bonham is late to the snare at 6 mins 17 secs. Heaven forfend.

Elsewhere, the opening one-two knockout of The Song Remains The Same and The Rain Song are similarly stripped and X-rayed, revealing layers of guitars, a propulsive bass line that’s rewriting the rules as it goes along, and a perfectly phrased grainy vocal brimming with easy grace. This is the sound of a band operating at dizzying heights.

Sometimes it’s easy to view greatness in the present, untethered from its genesis, seemingly immovable: it was great, it is great, it will always be great. The problem with this is that it takes us further from the moments where disparate factors collided to create something greater than the sum of their parts. These mixes can be viewed as keys to unlock these moments – snapshots of history in the making. Their legacy is legion.